Top of the Pops

Just a note that I’ll respond to the Putin-Biden summit proposal for the entirety of tomorrow’s brief and Friday will be on Eurasia.

The members of the EAEU are discussing potentially bringing a delegation from Azerbaijan into the fold on the bloc’s inter-governmental council meeting April 29-30 in Kazan’. Yerevan has to agree to the proposal, which may well happen, but if government is serious about working through the mechanisms by which the new project rail corridor running to Dagestan will boost the country’s economic fortune, it’s in its interest to include Baku in discussions on customs harmonization and related regulatory barriers. This latest initiative gives new half (quarter?)-life to Russia’s grandiose ambitions to form a “Eurasian partnership” bringing China, former Soviet republics, Iran, and even ASEAN together into a hodgepodge supra-national economic structure. It still makes little sense given Russia’s trade and economic policies, but this push is an important one to follow for the post-war settlement in the South Caucasus. One of the major economic flashpoints is Baku’s seizure of gold deposits from Nagorno-Karabakh, of which Demirli/Kashen and Gyzilibulakh/Drmbon provided an estimated 32% of Karabakh’s revenues alone:

As always, the problem with the EAEU as an economic space is the extent to which accumulation drives domestic economic policies for members — reserve accumulation via hydrocarbon exports, precious metals extraction, agricultural exports when possible, and good, old-fashioned consumer demand suppression. Ongoing tensions over the return of prisoners also hang over any invitation being extended. But the biggest winner in all this is Aliyev, who’s created more room to maneuver with Moscow giving him more space to court the EAEU while simultaneously seeking to expand its military and security cooperation with Turkey, now aimed at defense industry ties. Much of these agreements is symbolic. Symbols can still be parlayed into concrete concessions or gains. Azerbaijan’s stated it will complete construction of its section of the proposed railway to Armenia via Karabakh in 2-2.5 years’ time. Let the real negotiations begin.

What’s going on?

MinEnergo has reached an agreement with 14 Russian refineries to support modernization efforts to get refiners to invest 800 billon rubles ($10.6 billion) through 2026. 30 specific upgrades/projects are included in the list of projects, including a net increase of 3.6 million tons throughput capacity for class K5 benzine and to hit 25 million tons of throughput for K5 diesel. Doing so would match rising EU standards for fuel quality, crucial to increase product exports given that the expected decline of European refining capacity could create better export margins in years to come. The ministry expects more agreements to come, having reached a separate one worth 150 billion rubles with Novatek and Lukoil respectively. A slight increase in production capacity also resolves a lingering obsession for Moscow planners — the country’s refining complex can provide about 100% of its fuel needs, but lacks any spare capacity. That spare capacity then functions as a better source of export earnings when demand’s weaker domestically, helping the current account during slower periods in Russia or else absorbing increases in demand to allow domestic price control measures to do their work. These investments will also raise the share of “light” products up from 62% of throughput towards 75%, which is where it’s at on developed markets. The takeaway is that the price control system forces the ministry to negotiate what are effectively informal deals or guarantees with refiners to make sure they invest. It’s not the investment climate that’s to blame, but market regulations.

Corporate bankruptcy levels are ticking up, but are still lower than they were pre-crisis, mostly thanks to lower interest rates on top of the support schema from last year’s crisis measures. They’re down, however, 8.6% year-on-year as one might expect from the events leading up to the oil price shock last March:

Blue = number of bankruptcies per month Red = adjusted for seasonality

Construction and machine manufacture saw bankruptcy rates rise 1.3% and 5.8% respectively despite the net fall, which hints at trouble for firms exposed to demand pressures during the recovery. But in good news, there’s no evidence as of yet that there’ll be a surge in bankruptcies as the moratorium measures have been lifted or pulled back and debtors have renegotiated payment terms with creditors. Some of that is likely longer timelines for repayment on top of zero-interest support to maintain employment helping a lot. Debt restructuring, the limited effectiveness of using bankruptcy measures in Russia, and the statistical gap for recording purposes all play a part. It takes a few months for bankruptcy applications to be noted statistically, which I suspect is the biggest reason we haven’t seen a bigger surge given the relative increase from late 2020 is still fairly steep for the recent data available. Worth watching closely, as well as for what Putin announces on the 21st addressing the federal assembly.

MinEkonomiki has a bright idea — give independent hydrogen producers access to Gazprom’s pipeline network. The problem is how to separate it from natural gas and the costs involved. All the same, the ministry has a working roadmap for pivoting to export the fuel down the line. Current projections put Russian exports in the (massive) range of 7.9 million tons to 33.4 million tons annually by 2050 led by Gazprom, Novatek, and Rosatom. One of the first proposed legal changes to support the development of the sector is to shift regulations to allow hydrogen pipeline infrastructure to be built alongside existing gas pipelines so that they fall within the “protected zone.” It’s theoretically possible to separate hydrogen from natural gas at discrete stations, such that the overhead using existing infrastructure would be lower than having to build an entirely new system from scratch. The Blue Sky thinking is that Russia will account for at least 20% of the global market by 2030. That remains to be seen, particularly given the country’s poor track record sustaining investment levels. However, it goes to show that the development of hydrogen exports may further weaken Gazprom’s relative position as a monopolist in practical terms. Once other large firms are given access to its pipelines, it becomes more difficult to maintain its privileged position, especially since Novatek and Rosatom are better managed. Until the technical problems of whether they can mix hydrogen and natural gas and then separate them safely are resolved, it’s a highly speculative matter. But the direction of travel is clear — the old monopolists and leading SOE giants Gazprom and Rosneft may keep generating massive tax receipts, but are losing political ground domestically as a result of the changing energy landscape.

Maxim Reshetnikov is now briefing that the cap and trade-esque emissions scheme now being piloted in Sakhalin and, soon, Kaliningrad will be implemented nationally next year. MinEkonomiki is leaving the Duma considerable wiggle room by pointedly linking economic growth to an increase in emissions, citing the need to balance regulations against socioeconomic development needs. What’s left out, of course, is that rich nations have already made massive progress decoupling growth from emissions. The issue is the level of development, and since services play a smaller role in the Russian economy, there’s theoretically scope to (relatively) quickly make that pivot under certain reform scenarios. The law targets big firms creating more than 150,000 tons of emissions annually first by requiring them to report it all, then expanding that requirement to firms at the 50,000 ton benchmark in 2024. It’s painted as responsible stewardship when in reality, they’re just trying to ram it down the throats of the big exporters who’ll be first hit by EU regulations and leaving SMEs hanging and smaller exporters hanging. It’s a logical approach given how slow implementation tends to be in Russia, but one that benefits the largest firms. There isn’t even a payment structure being proposed for businesses domestically that would incentivize reductions in the current Duma bill. These are important steps to take, but too cautious. Regulatory arbitrage is a much more effective trade and industrial strategy when the US isn’t implicitly onboard with the process. But carbon pricing is a matter for world trade, and soon enough, we should expect attempts at WTO deliberations trying to demarcate differentiated requirements that over time converge. They’ll probably fail, but in the meanwhile the export losses will mount without more aggressive domestic policy in Russia.

COVID Status Report

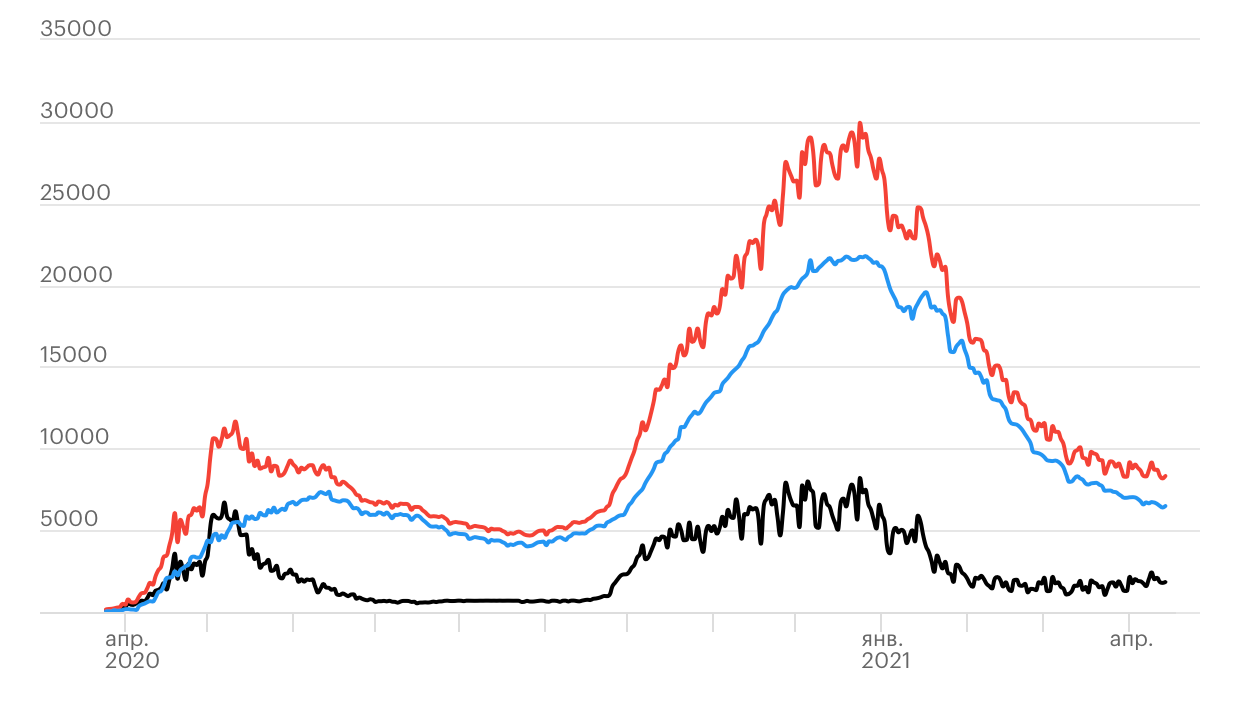

8,326 new cases and 399 deaths recorded for the last day. As we can see from the Operational Staff data, the decline rate over the last month now does more solidly appear to be hitting a floor:

Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow Black = Moscow

Couple that with Russia becoming the likely world leader in excess mortality — up 28% now — and there’s more and more reason to worry about another wave. The decline in the regions is what’s driven the % decline week-on-week and it’s nearly flat now. The collapse of tourism, most recently hammered by the ban on most flights to Turkey, is a positive indicator for future infections. The more people move around, the harder it is to contain the spread of the virus. The odder thing is seeing RDIF head Kirill Dmitriev schedule an interview with CNBC so they could ask about risks for Sputnik vaccines since it uses a viral vector like the now controversial Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca vaccines, but he promptly canceled. There’s clearly concern about the messaging and optics of admitting the possibility of any risk. It’s just unclear if that’s a matter for vaccine exports given the underperformance of the Sinovac vaccine relative to competitors or about domestic audiences since the government really needs the public to buy into the vaccination drive more quickly. Communications signals suggest the anxiety is rising.

Hey! Must be the money

I had a brief interaction with Michael Kofman and Brian Taylor while up late last night on Twitter that I’ve been thinking about since. Does Russia have a guns or butter problem or is are the resource constraints it faces entirely self-imposed? The issue is all the more salient now that a new armaments procurements program for 2024-2033 estimated to be worth “at least” 21-22 trillion rubles ($277.62-290.84 billion) in total has been announced. The thread came in response to this tweet responding to Levada polling that shows only 12% of Russians prioritize military might over economic growth and now 83% politically prioritize wellbeing:

The basic arguments are as follows: Kudrin warned that excessively high spending levels on defense would sap the economy and state of necessary investment elsewhere to the detriment of growth, military spending flatlined in real terms but rose as a % of budget expenditure while services spending declined, defense spending is inefficient but maintains strategic sectors of the economy, and Russia’s shown it has far more capacity to borrow and spend, which means the scarcity of resources for public services AND the military budget not rising further are ultimately political choices. I certainly agree with the last point in terms of Russian macroeconomic policy, but think that the revealed governing ideology of economic and budget policymaking as well as the cumulative effects of austerity have created a more visible guns or butter problem over time due to the structural impact they have on the political economy of the Russian system. The issue isn’t whether you buy more guns or more butter. Russia can have both. Rather the trouble lies in how much of that butter is poorly made with the help of gun manufacturers or various interventions and sector relationships between whoever’s selling either. You can have a guns or butter problem without the issue strictly being how much money there is to go around because of the structural effects existing policies and the defense sector can have, especially when the self-imposed scarcity of funding creates worrying tradeoffs for opportunity costs that accumulate over time.

If we look at % allocations of budget expenditure based on MinFin categories, there’s not a particularly compelling case for defense eating up too large a share of the budget. It’s share has also declined since 2017:

Social policy has gotten more expensive for the obvious reason that the country’s aging and the regime politically depends on the fixed incomes from the state to deliver public support and votes. Economic investment has broadly trailed defense and security spending, but have been analogous. Mind that this is assuming we can take the MinFin data at face value. We can’t, not just because true spending levels are effectively classified such that the topline figure is a ballpark one, but also because of the ways that defense spending is hidden into other categories and props up other sectors. The military frequently provides support for construction works carried out by RZhD and other state firms in remote areas, when drilling and engineering support is needed, and so on, the effect of which is to take something that appears to be economic spending on MinFin’s balance sheet and transform it into revenues for the defense sector. In theory, the social good and economic activity brought by infrastructure construction makes this an acceptable tradeoff. In practice, it inflates costs without freeing up much in the way of resources for either RZhD or the military, effectively acting as an internal rent mechanism shuffling money around. Subsidy support to Rosatom’s Arctic projects is dual-use since it props up R&D and the nuclear weapons complex through internal corporate transfers. The same logic applies to the civilian aviation sector when corporations produce both military and commercial planes. Military demand is locked in regardless of business cycle, civilian demand is not, barring state procurements. Military spending acts as a multiplier for potential productive capacity in this regard, but does not necessarily create growth for the economy as a result. Pulling some intuitive comparisons, here are a few ratios for spending/surpluses and deficits against the NWF and oil & gas revenues:

Defense spending levels have actually often been close to a 1-to-1 ratio or in the bounds of .75-1.25 against the National Welfare Fund where excess hydrocarbon revenues are deposited. Social spending vs. oil & gas revenues has shot up, a useful gut check given that the implicit social contract of soaking the oil sector was that it allowed the flat tax reform to bring more informal economic activity into the formal economy and avoid burdensome tax rates on the population. The surplus/deficit measure is just a way of visualizing policymakers’ reticence to take on deficits and keep spending levels within the range of what could be largely covered by liquid reserves in hand if need be. So there is no guns or butter dilemma based on the official % figures available. There are many when you consider opportunity costs and economic distortions on top of the ideological strictures of monetarist austerity and the lack of trust the state has in its own ability to invest because of corruption, waste, and mismanagement.

For instance, official defense spending as % of GDP peaked in the 5-6% range in 2015-2016. Some of that hike comes from economic contraction, but also because of the ongoing commitment to the armaments program started in 2007. Had 1-2% less of GDP been spent on defense procurements and instead directed towards income support or infrastructure development, real incomes would likely not have continued their same decline arc and, in a best case scenario (somewhat unlikely I admit given institutional challenges), you’d see a higher growth path post-2016 that would then create more revenues and reduce pressure on social services to allow for more future defense spending. There are two basic problems with defense spending in Russia that precede the inter-sector problems that can arise: the state is the only domestic consumer and exports have been used to reduce the burden on the budget further. Any decline of earnings from the latter has to be compensated by an increase of spending from the state. The current armaments program under development to be unveiled officially on September 1 has to square with MinEkonomiki’s growth forecast through 2035. Weaker growth lowers the spending ceiling. It’s easy to get caught up in % GDP debates when absolute levels of spending are just as important. Spending 3-4% of GDP after having achieved 2+% growth for 8 years is quite different than spending 4-6% during 8 years of real income decline and virtually no economic growth, especially since the price inflation dynamics hurting Russian consumers and now lots of industries pass through into the defense sector. Growth and rising incomes are a better long-term release valve than higher interest rates for problems like those seen now.

The strongest counter argument against critics of Russia’s approach is that higher levels of Russian defense spending support strategic industries, the high-tech sector, and don’t impose a significant macroeconomic drag. The problem with this argument is that keeping industries alive at suboptimal output rates with lots of slack covered via budget transfers actually destroys economic value over time because budget funds in various ways flow to these firms without adequate demand levels, whether due to self-imposed limits on the defense budget or, much more importantly, the lack of private sector spending power. You end up with large investments that don’t lead to significant expansions of productive capacity and higher wages/incomes. Take the Rosstat data on the physical production of materials for nano-industries that are core to Russia’s tech aspirations. Output has been effectively stagnant or, on average, lower than it was in 2013 in the last 8 years. If one compares apples to oranges with then current prices thanks to Rosstat’s brilliance, investment per capita ostensibly tied to a push for higher-tech production rose a strong 46.5% from 2013 to 2020. Factor in a halving of the exchange rate and inflation and that increase reflects abysmal performance. And the higher share of hi-tech output doesn’t mean much more value’s being created because of physical turnover, inflation, and the loss of value for fixed assets.

Rosstat calculations for the depreciation rate of fixed assets used for military security show the annual depreciation was higher than 40% 2017-2019 and that total average fixed asset depreciation rates in Russia for those years were around 49.5%. In other words, when the state builds something for the military’s security (vague as to what that means, but still useful), it loses 2/5 of its economic value in the first year and most fixed assets in Russia halve in value in a year. That means much higher levels of investment into replacements from wear and tear — a tricky stat but one that could reflect the climactic conditions in much of Russia that reduce the use-life of lots of equipment and goods. If you’re throwing money at procurements for goods that lost 40% of their value in a year from wear and tear and it’s not supporting growth elsewhere, suffice it to say that while the main culprit is austerity, there’s a problem creating value taking place across the economy worsened by the effective subsidy of a sector now struggling to meet civilian demand from the proposed reform approach to the military-industrial complex. In the UK between 1970 and 2013, ICT hardware used for hi-tech purposes depreciated an average of 46% annually in value. Anyone who’s dealt with Apple knows the pain of obsolescence and how fast erstwhile hi-tech goods can lose their value. It’s a similar problem when you’re talking about high-end systems used for targeting guidance, radar, aircraft, etc. Once you launch a new platform, particularly one that’s theoretically more demanding technologically, you have to grapple with the burn rate at which stuff falls apart, adjust supply chains accordingly, and have some built in slack capacity to address bottlenecks in a crisis.

Depreciation doesn’t quite capture that in a military context, but the high rates across the economy show that there’s an argument to be made that these programs impose long-term costs because defense firms able to rely on state contracts are now trying to poach industrial business they may not have the right competencies or market conditions to support. Maintaining your own semiconductor capacity and chip manufacture and the like is a national priority, but there are many ways to go about maintaining that production. Taking the institutional structure of the defense sector as a given in the pursuit of the stated goal of growing production it’s thus far not been proven able to dodges the core of the guns or butter riddle: assuming these suboptimal outcomes and inefficiencies are part of the design of a statist economy, does the sector deliver on the assumed premise under which it operates? The evidence so far suggests not in economic terms, though it has been able to retool the Russian military and make it more competitive, able, and well-equipped. Higher levels of spending may well be needed to maintain the edge in the future, particularly if the prolonged crisis of underinvestment across the real economy since 2012 continues indefinitely. The problem isn’t so much budget. It’s that military firms are trying to move onto more civilian turf because they face pressure to do so from Moscow so as to reduce the state’s macroeconomic exposure and lighten the load on the budget. Worse, they aren’t necessarily competent when it comes to maximizing efficiency given their incentives. It’s a perfect storm that may create a host of inter-sector ripple effects depressing growth and challenging the regime, just not with the traditional dilemma we might expect with the old dichotomy of social welfare vs. martial prowess.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).