Top of the Pops

Dmitry Rogozin, not known for his managerial competence, wants to keep being the guy dreaming of a Russian return to the moon among other things. As befits that aim, yesterday he called out the “colossal” financial limitations facing Roskosmos in his mission to one-up the West, one-up Elon Musk, and do more than make up for lost export revenues selling engines to the United States. Space spending was capped at 250.4 billion rubles ($3.28 billion) for the 2021 budget, a 7.5% cut from 2020. Putin may announced an additional 1.6 trillion rubles ($21 billion) in R&D spending through 2024, but it seems that Rogozin’s continued bungling has pushed space to the budgetary back burner even more than was the case pre-COVID. If he’s serious about building an independent Russian space station and excluding foreign involvement, that’s obviously not going to work. He claims it’ll be done by 2025. Few priority programs are truly left to chance, even factoring in the frequently personalist nature of agenda and budget-setting in Moscow. Space, it seems, is now completely a personal policy vehicle given the short shrift it’s receiving politically. President Trump’s creation of Space Force — lampooned by countless people seemingly unaware that the US military had internally been calling for a space department since the mid-90s — doesn’t seem to have yet triggered an equal reaction in Moscow. Ghosts of Star Wars past go begging.

Internal policy pressures to properly fund Rogozin’s grandiose plans may shift as the US makes progress establishing the parameters of Space Force. They’ve just launched a new procurements platform to improve the efficiency of systems acquisitions and cut out the Air Force from bids. Bloomberg has writers pushing the line that Russia and China are launching an arms race for space and to the extent that it’s true, Chinese funding behind Russian technology will be the story as long as the two trust each other. That may be true for strictly military applications in the Russian case, but Roskosmos’ woes suggest that the more exploratory edge of the technological frontier needed to expand Russia’s presence in space is a far lower priority than maintaining capabilities to asymmetrically offset the in-built US advantage on that front, especially since the US Defense Department is on its way to becoming one of, if not the largest consumer of space innovations from the private sector globally. The announced boost in R&D yesterday may play a part in trying to keep pace, even if it’s a relatively insignificant infusion when you annualize the figures. It’s not the top of my priority list, but I’d follow this up later in the year since it’s hard to imagine there isn’t a considerable degree of consternation in Moscow about Roskosmos’ ongoing performance issues.

What’s going on?

One of Putin’s direct retail offerings yesterday was to order the extension of the new Moscow-Kazan highway — intended to increase high-speed traffic and reduce travel times for people and goods — all the way to Ekaterinburg. He set 2024 as the target date, talking up how its completion would link the Baltic to the Urals and road expansions around Moscow. Consider briefly the costs and distance involved thus far with the project without the extension. 530 billion rubles ($6.95 billion) to build a route that, all told, is 794 kilometers long. The project cost is in the range of 667 million rubles ($8.75 million) per kilometer, which to put it lightly is a lot. I tried rooting around for comparative benchmarks despite difficulty getting good data comparisons, but without a great source, that price point isn’t that much less than prices for road construction in the UK where land is far more scarce, the population more dense, and labor/input considerably higher. That’s not the level of price inflation you’d likely see on a road project in the Russian Far East, where local interests can exploit their physical distance from Moscow to extract more money out of projects in relative terms since land is much cheaper, but speaks to the problem of efficacy for fiscal policy. The spend on infrastructure needs to rise by an order of magnitude, but the more it rises, the more gets pocketed into offshore accounts showing up as capital outflows on the national balance sheet or else goes into acquiring property or luxury imported goods. These costs also likely understate the coming. revision upwards given how much tighter the labor market for construction has gotten. The expansion is estimated to cost in the range of 600-900 million rubles a kilometer, totaling out to another 240-360 billion rubles ($3.14-4.72 billion). That’s equivalent to most of the social spend that was announced.

AKRA and Golden Credit Rating teamed up to do a rundown of the cumulative GDP impact of major lockdown measures in 2020, and their estimated economic losses for Russia came out to roughly 5% of GDP since the GDP decline was measured at 3% vs. an expected 1.5-2% growth. In their finding, the average economic losses for each economy were more like 7.1% — Russia (3rd from left) held on to its ‘over-performer’ mantle:

Light Blue = general losses Red = actual decline/growth GDP Black = pre-pandemic forecast

It’s likely the perception of that over-performance contributed to the skimpy spending program Putin rolled out yesterday, estimated at just 400 billion rubles ($5.23 billion) which is under the original leak of a 500 billion ruble spending target. Presumably the exercise was intended to link economic losses with the strictness of public health measures taken. By default, it’s a re-litigation of the argument over whether COVID is a supply or a demand shock, with a bias towards supply-side analyses. Rosstat’s decision to bury the real income stats in support of Putin’s address suggests political pressure to confirm this view instead of drawing more obvious links between income levels, demand, and business activity. In reality, a mix of buoyant external demand in the US and China and price inflation for some major Russian exports fosters the false impression that domestic demand is in good shape — grain exports for Jan.-Feb. doubled despite the price control measures because of how much better the earnings were abroad as prices have risen. Until the economic institutions like ratings agencies challenge the supply side paradigm, the regime will lack substantive informational feedback, feedback that some business lobbies support given their own interests.

In the latest sign that the recovery is worse than advertised, 25% of consumer debt payments were overdue as of April 1 according to finanz.ru. That’s a 5.3% increase year-on-year from the initial lockdown and pandemic hit to jobs and earnings when the oil price was in the toilet. Note that these are figures based on being 90 days or more late on payments. 30.4% of microloans are overdue (+4.8% YoY), 7.5% of autoloans are overdue (+1% YoY), only 1.5% of mortgages are overdue (+0.1% YoY), and 7% of credit card debt is overdue (-0.8% YoY). These figures speak to the massive degree of inequality hidden by statistics that otherwise suggest a level of pain shared somewhat evenly. Microloans are the tell, since they’re often given out by the riskiest credit institutions with the riskiest lending profile. Mortgage delinquency was held lower through policy intervention and suppressed rates, plus the massive expansion of mortgage issuance would have initially been taken up by more creditworthy people and filtered down the longer the program ran for the obvious reason that the number of creditworthy Russians keeps falling the lower incomes fall. Since we’re talking about a 90 day timeline, this wouldn’t cover any mortgages issued after the end of 2020 and that data might look a bit different a year from now. Falling credit card delinquency would reflect falling appetite for consumer spending as Russians are forced to save more or else are earning less. According to Frank RG half of all cars are bought on credit as is 25% of all home appliances. That tells you two things — Russians prefer to pay cash for these goods when they can and have to save for longer to do so, and that any further increase in delinquency rates for non-credit card debt is likely to correspond to lower levels of consumption, likely reflected in reduced delinquency rates for credit cards. It’s not a terrible picture or a ‘debt bubble,’ but it’s a troubling dynamic.

Old MinFin and banking hand Oleg Viugin and professor Konstantin Yegorov spoke on a podcast for VTimes about non-standard economic policies, chiefly monetary policy that has had to adjust to the realities of COVID and a world of constant low rates. What’s interesting to witness is how the evolution of the monetary and fiscal policy paradigm in the US leaks over into the Russian context with the recognition that setting the key rate as low as 4.25% was a non-standard move by the Central Bank. But capital outflow risks from rate cuts were mitigated by just how low they went across the entire OECD. The bigger point they raise is that non-standard policy in Russia can’t approximate the Fed’s bond purchasing programs because of how much smaller the market is — there aren’t enough private bonds in circulation and being issued to pair with sovereign debt issuances in order to manage risks. But what per their discussion, the extension of ultra-low rate credits effectively subsidized by the state is what non-standard policy in Russia looks like. That makes sense, though I disagree with them insofar as the response to the Global Financial Crisis showed definitively that bond markets reflect political choices and aren’t strictly constrained by the size of the private market. Last year’s bank-led bond purchases in Russia implied that demand actually outstripped issuances, though this gets muddled by the fact that the state could effectively order banks to do it. But the big picture reality in the West is true in Russia — lower rates reduce the effectiveness of monetary policy the longer they’re in place, which means fiscal policy has to actually resolve the problem of demand constraints in tandem with monetary policy. Still, the conversation linked monetary policy last year with increased inflation despite the lack of clear evidence from the real economy that money printing was responsible for most price increases.

COVID Status Report

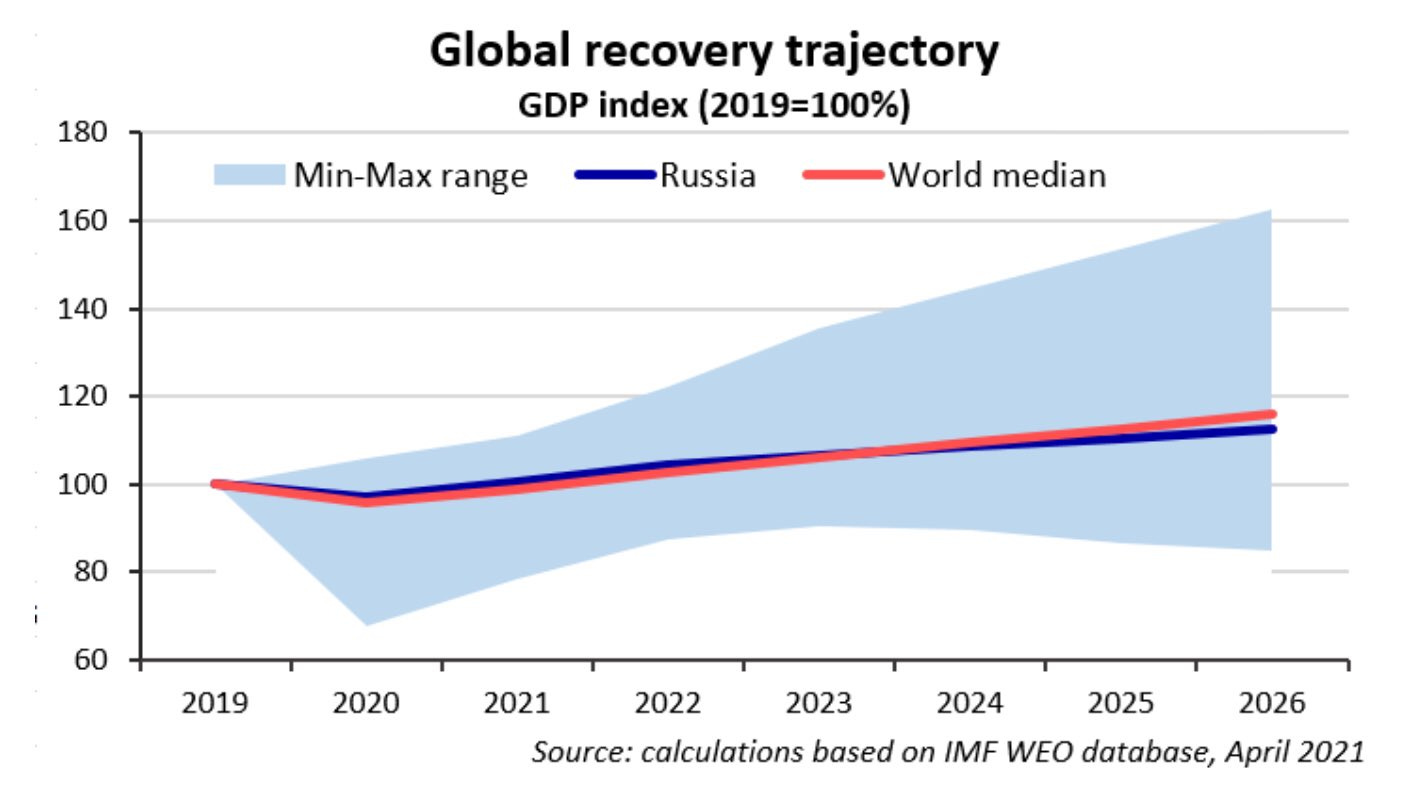

Russia recorded 8,996 new cases and 397 deaths in the last 24 hours. Based on the chart breakdown RBK usually runs, the uptick is entirely in Moscow, which is where the warnings of a 3rd wave have been loudest. Putin talked up the the three vaccines Russian manufacturers and scientists had worked up yesterday, but the real story of the new-look strategy after his call for all Russians to get vaccinated came from Vyacheslav Volodin in the Duma — he wants Russia Inc. to embark on a collective patriotic campaign to push employees and customers alike to get their jabs. Without it, Russia’s already weak recovery path, cushioned by an expected return to pre-COVID GDP levels by the end of this year, will look even weaker:

Out of Gas

You can hear the mental gears grinding in Moscow excited at the prospect that new calls from the Biden administration to end coal-fired power generation globally will launch a new scramble for natural gas markets. If one takes the accounts from the Vedomosti piece that’s linked seriously, the planet will run out of the metals needed for most sources of renewable energy. No explanation is provided, of course, aside from the quote. I’ll return to that point later. Coal power is the weakest link in the global campaign against emissions, and its impending decline provides the basis for Russia’s plans to increase LNG production capacity to 140 million tons annually by 2035 and claim 20% of the global market. Emerging markets aren’t going to be able to afford the relative increase in power prices that tends to accompany greater renewables adoption unless there’s cheap baseload power sources able to cover any shortfalls from the intermittency of wind, solar, and similar power sources. To that end in Europe, Angela Merkel informed the Council of Europe’s parliamentary assembly two days ago that it remained Germany’s policy to complete Nord Stream 2 while pushing for a legal-political framework that protects Ukraine’s status as a transit state for piped gas exports. That’s surely to Gazprom’s benefit over the long haul in Europe, though the actual level of demand is unclear since the next generation of energy sector investment will entail as much fuel switching away from fossil fuels as possible. There’s a problem buried in that dynamic for Gazprom’s position in Europe, which remains Russia’s largest foreign natural gas export market: Norway’s net zero and emissions reduction commitments are unlikely to affect its production levels significantly and rising natural gas demand could benefit US shale drillers as well.

Norway’s natural gas production is expected to maintain at current levels as the oil market stabilizes and associated gas from oil wells as well as pure gas plays perform better. Offshore wells can’t be halted once they’re launched because of the high level of capital expenditure needed to launch them in the first place, unlike cheap onshore conventional production or shale wells that can more readily be idled. In other words, any additional investment into output is likelier than not to increase production, but there isn’t any reason to expect significant decline during the early stages of the transition away from coal on emerging markets, should it materialize. It gets harder to see that the close we get to 2030, but if the dire predictions about baseload prices rising in Europe for natural gas — the experience in Germany as it shuts down coal and nuclear power plants — then Norway’s output will be profitable and politically salient for the EU. Maintaining current production levels will limit the market share advantage Gazprom ostensibly has since it would tank prices with over-production. Russia’s dominant import share will rise in % terms, but so will Norway’s as demand likely falls. The paradox, however, for natural gas prices is that if future marginal demand growth comes as a result of the need first to fuel switch, and then provide baseload for renewables, you’d potentially see a long-term increase in wholesale and retail prices in a manner oil is highly unlikely to see since accelerating road fuel substitutions means that plastics, petrochemicals, and other types of consumption will be increasingly important for demand scenario modeling over traditional GDP-linked measures based off gasoline/diesel and their link to business and consumption activity levels.

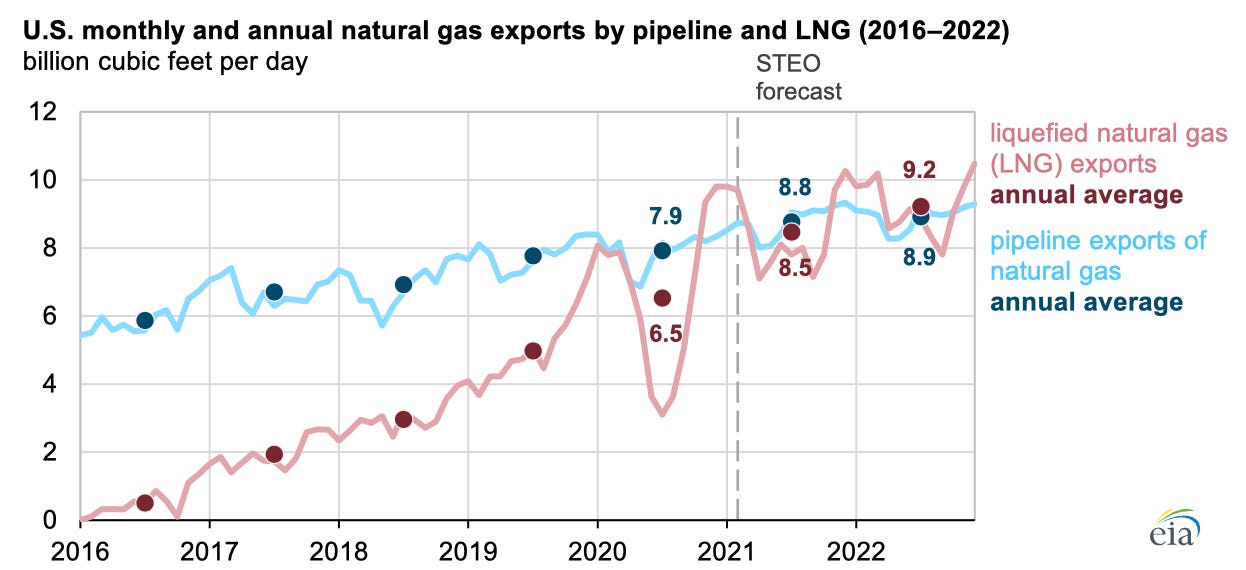

US shale may never be the same again when it comes to oil — I’m a bit more sanguine about its prospects given the Fed policy outlook, but think growth expectations need to be adjusted — but natural gas will sustain much of its activity. To be clear, that doesn't mean a “gas renaissance” is in the offing. There’s a global gut of LNG capacity at the moment, one that Russian plans will have to grapple with. But it’s expected that no new LNG projects in the US will take an investment decision this year because of the difficulty securing long-term contracts:

But they aren’t going anywhere, which means pricing dynamics on LNG markets that are increasingly connected matter alongside the baseload and intermittency problem. There’s also the issue of domestic demand in the US. So long as the US is now committed to halve its emissions by 2030, the massive amount of existing natural gas wells and infrastructure across the country will be rendered worthless if some of that capacity isn’t reoriented towards exports as its phased out for domestic power generation and heating. The underlying export growth trend could continue so long as the industry is able to maintain its export competitiveness by reducing emissions and building on its success reducing flaring:

Adam Tooze’s writeup on the ambition (and lack thereof) in Biden’s climate plans is a great read in the limits of the possible, it runs up against the biggest gap in the ‘green discourse’ around accelerating transition:

“With sights now set on net zero by 2050, there is no longer any room for fudges. The Biden administration needs to change the direction of energy policy radically, from Obama’s “all of the above” to a systematic exit from fossil fuels. It needs to find both economic and technical solutions to make a green energy system viable.”

The rest of the piece well details the political obstacles, while touching more lightly on economic obstacles. But most of the loudest voices calling for far more radical policy programs don’t seem to be particularly engaged with the technical problem and the unintended consequences more radical approaches entail. The baseload price effect is the most interesting problem for Russia’s mad scramble since it can actually benefit Russia’s competitors as much as it does Gazprom or Novatek unless it bears an ever-worsening subsidy burden maintaining its industry. It’s also funny that it seems so confident that material shortages will clip the energy transition’s wings. Technological improvement continuously increases the net amount of production that can be yielded from existing finds and academic models tend to show that direct depletion isn’t a risk for decades to come, and that excludes the potential knock-on effects of carbon pricing on the profitability of recycling material, improving effective use-lives for batteries, and so on. The bigger risk is that these transitions will, at least during the initial stages, entail an increase in energy prices, which can only be avoided in the longer-term ironically through the taxation of carbon emissions. You need to build an economic rationale for redundant capacity and create a (diminishing) fiscal capacity to offset the price effects through capacity investments, home battery deployments, and more. Technical questions matter more and more the closer the political goalposts shift on these policy agendas. That Russia is banking on a renewed war for natural gas markets speaks to Moscow’s policy paralysis. It may beat US exporters on a price point basis, but when betting on carbon-intensive assets as the depreciation risks of these assets rise, there are only two types of players left: the quick and the dead. Moscow’s not known for being quick, especially when LNG creates fewer rents at home.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).