Things fall apart

The collapse of the ANSF and US withdrawal are weighing more on Moscow's plans

Top of the Pops

BP’s annual Statistical Review of World Energy report just dropped and it’s worth a look through for anyone intrigued by this kind of data gathering and big picture narrative work. Tl;dr — 2020 was a crazy year of outliers and extremes. One of the useful tidbits from more recent history, aside from oil demand growth structurally declining pre-COVID, is that in any given year post-2000 market participants tend to over-estimate overall power demand growth. But that dynamic doesn’t necessarily make sense in a post-COVID world because of a great deal of ‘greening’ requires rising electricity consumption to offset the use of other types of fuel sources, nor can it capture the pace of technological adoption and how that’ll effect demand. After all, we just lived through a 40-year super cycle of economic policymaking biased towards deflation over inflation broadly speaking. The % share for renewables vs. coal is useful to consider in that light:

Coal is declining more slowly or else at the same pace that renewables are rising. That’s not good enough, and some of that is a result of nuclear’s decline in the global energy mix, with Europe in particular decommissioning more nuclear capacity than hydrocarbon power generating capacity. Since China’s not committed to peak coal capacity until 2025, reductions are going to have to come elsewhere and fast. Development politics are about to get incredibly messy. According to BP’s chief economist Spencer Dale, you can infer a carbon price of $1,400 per ton from the decline seen last year relative to GDP. And that decline would only get us 85% of the way to a 2 degree scenario if it continued on trend. The scale of investment needs is immense.

What’s going on?

In the latest sign that Moscow’s scrambling to prepare for the energy transition, MinEkonomiki is now laying out plans to diversify the economies of Kemerovskaya oblast’ and Komi republic away from coal. The plan looks like a wishlist of 100 projects worth a combined 500 billion rubles ($6.72. billion) to be launched over the next 5 years. In Kemerovo, for instance, coal companies pay 40% of all tax receipts. Any major dip in export earnings has huge consequences for regional budgets (even if they’re scrambling to export more while they can). Econ minister Maxim Reshetnikov’s proposing to condition investments into further rail infrastructure paid for using federal resources with requirements that the regional governments invest into non-coal industries. Of the 100 projects proposed, 78 are located in Kemerovo and estimated to cost a combined 376.4 billion rubles ($5.01 billion) in non-budgetary investments through 2026. The biggest individual project is a proposed ammonia and urea plant for Roman Trotsenko, owner of SDS Azot and coal assets in Taimyr, projected to cost 105 billion rubles ($1.41 billion). Several others are listed, all of them touch on either commodities production and exports or modernizing existing infrastructure. Putin personally ordered the review for diversification purposes as part of the regime’s pivot on net zero pledges, recognizing that future declines in coal demand will pose serious socioeconomic problems for regions too dependent on coal. What’s happening so far, however, is indicative of the challenge of diversification we’ve seen elsewhere in the Gulf. When your best competitive advantages in trade are fixed assets like hydrocarbon reserves, the best investments for returns move up the value chain for that commodity — think ammonia or urea in this case. You capture more of the value and margins are better at the project level, but systemically, you aren’t doing as much diversifying as it may seem. Curious to see how MinEkonomiki and others square that circle now that the government is mandating earnings from higher coal exports to Asia be re-invested into local economies.

Regional budgets have recovered strongly from last year for Jan.-June, with net regional revenues reaching 6.699 trillion rubles ($89.9 billion). That’s a 19% increase over the same period in 2020 and a 22% increase over 2019. Taxes on profits are one of the biggest drivers and accounted for about 31% of the increase — regions with large metallurgical firms are the biggest ‘winners’. But from the examples given by Kommersant, the recovery has uneven implications and if profits are a big part of the story, then a fair part of the increase is also inflation related:

Deficit/Surplus in blns rubles

Expenditures at the regional level have only risen 7%. That’s logical from the regions’ perspective, but effectively the beginnings of another bit of austerity mandated from the center. The government’s already looking to delay and minimize attention from Rosstat releases ahead of the September elections in a tacit admission that lots of underlying economic data is not nearly as rosy as MinEkonomiki wants the public to believe — remember Reshetnikov literally proposed rewriting income formulae to make it appear as though real incomes weren’t still declining. There’s creeping fear of a large spike in corporate bankruptcies in 3Q, though that won’t affect profit taxes since the biggest winners so far are Russia’s exporters. Inflows of investment are minimal this year — just $30 million for the last week. It’s not looking great for domestic-facing businesses the rest of the year. Still, regional budgets are clearly in far better shape, which will avert more borrowing stress from the center.

Russian Railways has come up with novel policy tool — agreeing to future tariff discounts. For the first time, the monopoly has agreed to offer freight operators a 30.4% discount on tariffs for methanol shipments from the Skovorodino plant currently under construction from 2024-2030. The thinking is straightforward — make rail more competitive in the future to lock in a cargo base, reduce route competition, and revenues to be able to better plan future investments. The discount will only remain valid as long as the plant ships no less than 800,000 tons of methanol annually by rail. The plant is expected to have a production capacity of 1 million tons annually when it launches in 2024 to be doubled to 2 million tons. Japanese conglomerate Marubeni has already contracted 500,000 tons annually for 20 years from the plant. Overall, this new approach to dealmaking is good for Russia’s logistics network. It helps avoid bottlenecks and provides steady demand for future earnings and investments, both of which are all the more important because of Russia’s stagnation. Without growth, an increase in earnings for any given sector generally has to indicate an increased cost elsewhere and RZhD is designed to be run with low margins since it’s a public utility serving loads of remote markets with domestic trade imbalances. What I’d watch for, however, is the response from other sectors and companies looking for favorable treatment. Ever since the Platon system was introduced post-Crimea amid said stagnation, firms have become more and more cost conscious for logistics, with lots of gains coming from firm-level modernization and adoption of techniques common on developed markets. Once one company gets a deal, others will want in and any time output falls short because of supply chain bottlenecks or investment delays — more likely the lower investment levels have fallen — the bigger the relative hit for those companies. These blows, however, are softened for any firms relying primarily on exports instead of domestic demand.

In hopes of further improving the investment and business climate within the bounds of what’s possible, MinEkonomiki is suggesting that a new appellate legal organ be created to settle out-of-court disputes over the valuation of assets. Appraisers dealing with so-called “self-regulated organizations” (SRO) have complained about the process as it stands. Valuation assessments are a massive pain in Russia for myriad reasons — the cadastral registry is often a mess, there are situations where businesses, individuals, or entire towns make use of assets no one legally owns, there’s room within bounds for bribery and similar pressures to be exerted on assessors or judges though that applies mostly to salient cases where someone wants a tax break or to move an excessively large sum around, or else the regulatory environment for businesses change constantly. How can you properly assess the value of a business asset when next week, the government might decide out of the blue to slap a new tariff or tax on your production or, conversely, subsidize what you’re doing? The main criticism levied at the initiative is that it’s seeking to solve a problem that already has a solution within existing mechanisms — consumers can lodge complaints about valuations to SROs who then consider the complaint and pass it on to an independent internal council for decision if it merits consideration. A new process will just reduce the role of appraisers and liquidate SROs, reducing the power of independent market actors to provide these valuations. In the last two years, only a few dozen complaints have been considered according to Maxim Skatov from the SRO Union Federation of Appraisal Professionals. That could be cause the SRO process is terrible, but more likely consumers just don’t trust legal institutions enough when things are contested to want to bother with the headaches. A new process won’t fix the latter problem and speaks to constant impulse in Russian policy: proposing new institutional arrangements because root and branch reform is politically impossible. Too many bureaucrats sit on too many rents. It’s easier to try to reduce the bargaining power of one bloc by creating another.

COVID Status Report

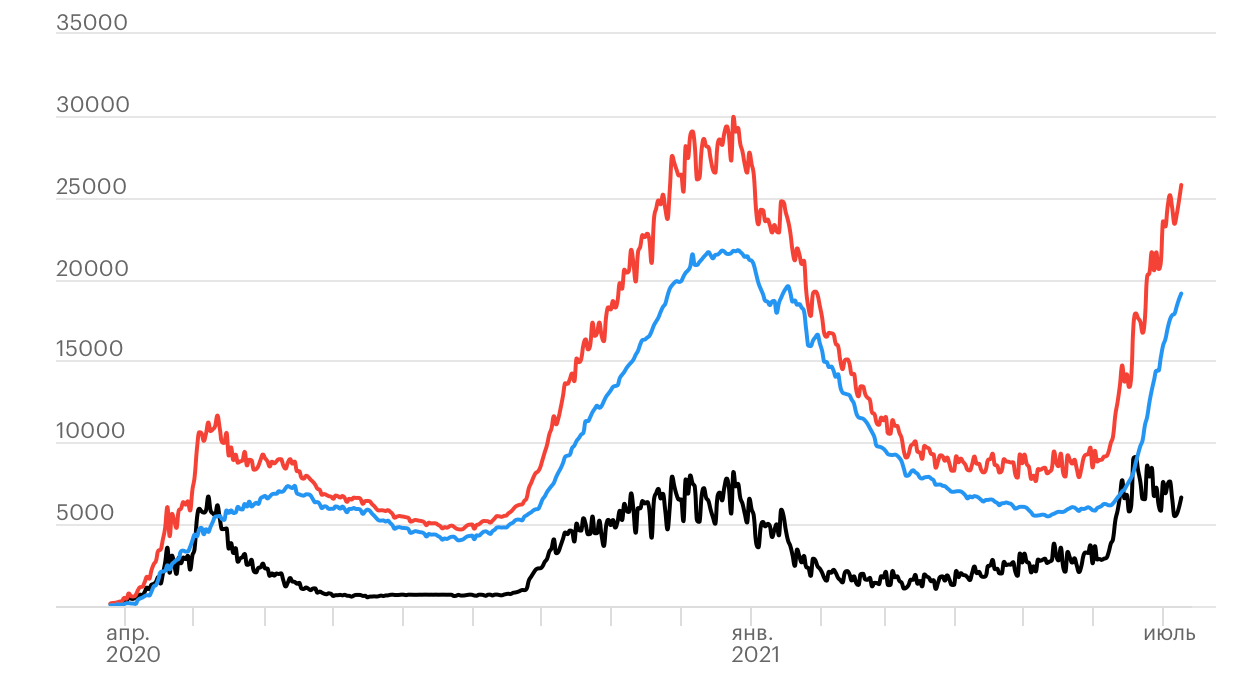

A post-January record 25,766 new cases and 726 deaths were reported in the last day. 16.73% of the population have now received at least one dose — Moscow’s at just 23.71% which should be worrying given it has the best capacity of anywhere in the country to ramp up, buy more vaccines, or do whatever else is needed. The Moscow Times did a fantastic job connecting the dots on how Aurugulf Health Investments, the Russian Direct Investment Fund’s contractor for various vaccine supply deals with developing countries, was given exclusive rights to sell Sputnik-V vaccines to 3rd party countries. Led by Sheikh Ahmed Dalmook al-Maktoum, the deal effectively gave the Emirati middlemen a pricing monopoly allowing them to massively markup prices and pocket the difference. Russia’s vaccine diplomacy is falling apart just as it’s now dashing to convince more Russians to get their shots as cases rise:

Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow Black = Moscow

Though the rate of rise in the regions is beginning to flatten slightly, it’s still far ahead of the last wave which strengthens the idea there’s a significantly higher peak to come. Anna Popova from Rospotrebnadzor went on record that no lockdowns or harsh COVID restrictions are necessary. They’re just going to ride it out while deaths and excess mortality figures keep climbing.

How much does an empire need?

Mikhail Mikhailovich Zadornov, former finance minister and now chairman of Otkrytiye Bank’s management board, gave an interview with Kommersant as part of its running series marking 30 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Zadornov hails from the wave of ‘liberalizers’ that eventually put forward the 500-day reform agenda along with the increasingly toxic Grigoriy Yavlinsky that politically morphed into Anatoly Chubais’ efforts to create a “shareholder democracy” that would lock in gains made for private property and the marketization of social and economic relations and policymaking in Russia. One salient point sticks out from the early part of the interview — Zadornov believes that a ‘Marshall Plan’ for Russia would have made the transition in 1992-1996 far more manageable and successful and would have been politically acceptable and possible had the USSR not collapsed into separate countries. If one were to offer a glib condensation of Zadornov’s guiding precepts by implication, he could be counted among Russia’s “imperial monetarists,” the various disciplines of Milton Friedman seen through the looking glass of the late Soviet economy (which was increasingly state capitalist rather than planned) who intuited, if never articulated, that fixing the Soviet economic and political system was far more manageable without the erection of borders, competing national elites with little incentive to forgo political power for the sake of markets, and the dissolution of countless supply chains. Zadornov was a core player in fashioning the post-default policy response and environment that established the deflationary economic paradigm Putin’s team inherited and eventually ‘perfected’ once it became politically necessary in 2011-2012. Even if this genus of liberals who wished to destroy the Soviet system abhorred conflict disagree with this or that military intervention, they at least saw the value of maintaining the Soviet economic space in a new form with inevitably imperial implications.

Later in the interview, he talks about ‘debt addiction’ and seems content that Russia’s escaped this trap by and large. He even seems confident that the expansion of mortgages among households with declining disposable incomes will end up improving their situation, a direct mirror to the logic of the Bush administration in the 2000s and the bargain struck by American elites for decades — Your wages won’t rise, but the value of your homes will in exchange. The most interesting point comes just after:

“I, as an economist, am saying that our sense of our own greatness utterly doesn’t correspond with our role in the world economy. It’s steadily declining and I, as an economist, might be exaggerating, but all military, political, geopolitical ambitions are limited by the size of your GDP. The defense budget is still about 3.5% of your GDP. If your economy isn’t growing, then all your ambitions…”

GDP is at best an imperfect proxy for a state’s ability to sustain its military power and geopolitical influence given the rise of cyber capabilities, asymmetric deployments of military personnel and weapons systems, strategic supply chains, and more. There’s also not necessarily so much of a debt problem as Zadornov would have us believe. But there are serious economic and political limitations on the projection of national power that the current COVID wave is making more observable and make his point more salient. State banks are effectively “boycotting” large purchases of Russian sovereign debt — demand for Russian debt has been minimal and demand relative to March and April has fallen over 90%. The question is why? Think of it this way. Why should state banks keep buying sovereign debt when they know a big rate hike is coming and consumer borrowing has probably peaked? As creditworthiness declines among borrowers, there’s more pressure to play it safe and more pressure to realize higher yields whenever the bank does decide to extend money, in this case buying a bond that’ll pay out over time. And further, why should state banks keep the state afloat if the state’s incapable of helping borrowers and the real economy in an effective fashion when it’s sorely needed? Last year and through the spring it made sense. Now that a new wave is kicking off and all the worse because household and SME company balance sheets are often in a more tenuous state, they’d be handing over rubles realizing lower returns as inflation keeps rising while the lending boom subsides without much non-export growth. The failure to spend money via budget deficit earlier has paradoxically made it harder to spend money now, imposing a harder budget constraint on the state than might otherwise have been necessary and worsening the likelihood that tax increases will outstrip expenditure increases once again. If banks expect bankruptcies and other longer-term scarring to be visible by the end of 3Q, of course they’d start laying off OFZs. “What have you done for me lately?” rules the day. Generating a budget surplus in these conditions will mean raising taxes.

This dynamic is playing out right as the situation in Afghanistan is falling apart. The US has left troops in Kabul with the promise of air support to ensure that president Ghani doesn’t fall, nor can the Taliban likely take Kabul. But they’ve begun to seize border crossings — they’ve reportedly seized Islam Qala through which most trade with Iran takes place after having seized several crossings with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. They’ve got a chokehold on the various trade and smuggling rents now and Russian officials just met with a Taliban delegation that offered the usual assurances of protection for different ethnic groups, responsible governance, and whatever else Moscow wanted to hear as they’ve taken control of as much as 2/3 of the country. Foreign powers have to deal with them. The Iranian government hosted Taliban negotiators in Tehran as well while Ankara commits troops to protect the airport in Kabul. President Biden moved up the official withdrawal timeline slightly to August 31 while the White House scrambles to find countries to host the Afghans who’ve provided support to the coalition mission and will undoubtedly be targeted by the Taliban. The message is clear — the Afghan National Security Forces are running. It’s not the fault of the US or NATO mission at this point. 2 decades of investment, time, and training weren’t enough. There are countless things to criticize about the execution of the war in Afghanistan, but at some point, locals have to fight for their own country.

None of this is evidence that stability lies on the horizon. Moscow now wants assurances that northern Afghanistan won’t be used to attack into bordering Central Asian states. The Taliban have promised to not allow IS to do so, in fitting with past commitments and their actions with the US in the recent past. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has made it clear that if attacks into Tajik territory take place, Russia will respond militarily. Moscow’s clearly got a full-blown security crisis on its hands now. All it’ll take is one local group trying to score some extra money or arms in a border raid to kick off a reaction that could quickly spiral into a diplomatic crisis with the Taliban. Kabul is trying to assure its neighbors that ANSF forces won’t keep pouring over borders, though it’s hard to imagine anyone takes them particularly seriously at this stage. And what’s more concerning is that Moscow’s diplomatic position on a resolution for the conflict — a coalition government in Kabul between the current administration and power blocs in the capital and Taliban — would be a death warrant for Ghani and his patronage networks. It’s not exactly like Bashar al Assad was keen to jointly govern and it’s not like anyone in Kabul who’s either profited off the war or else furiously hates the Taliban will go gently into that good night. In effect, Kabul will become a besieged island kept afloat through limited as necessary interventions by the US and presence of US/Turkish troops while Russia, Iran, and China maneuver with Pakistan and India to keep a lid on non-Taliban groups that pose a threat basing themselves in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s implosion is happening at a moment when the Russian state is struggling to borrow, facing an increasingly deadly wave of COVID, and the prospect of raising taxes while trying to deliver the right results in September’s Duma elections. Even the most ardent defenders of Russia’s enduring “great powerness” have to admit there’s a problem of political capacity here. When a great deal of a national foreign policy comes down to spinning plates in the air, there are only so many to add to the show before something slips and breaks. Biden’s speech on the withdrawal is worth a watch:

President Biden framed the entire speech around his visit to Kunar in 2008, one of if not the most dangerous places to deploy during the most intense phases of the US counter-terror and counter-insurgency mission in Afghanistan. What’s clear is that the White House has a strongly defined strategic sense of the withdrawal. Others may kick and scream about ceding defeat, the media, or cling to narratives about future terrorism threats or the protection of human rights. They pale in comparison to the basic political principle that American soldiers cannot ensure freedom for Afghans, only the Afghan people can, in the end, win any fight against the Taliban. The US has been mired in domestic political crisis for years now, a crisis that grinds on and leaves a slew of issues undecided to the detriment of the nation and global challenges like climate change. No doubt the administration is happy to hand off this particular plate to Moscow as the consequences of the decision become more stark with each passing day.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).