Top of the Pops

The crisis in Armenia' continues to escalate after the rest of the heads of the Armenian military have come to the defense of Onik Gasparyan, head of the General Staff fired by Prime Minister Pashinyan. Yesterday, the opposition called for talks with president Armen Sargsyan tomorrow, but only to discuss Pashinyan’s removal. The aim would then be to form a provisional temporary government while planning for an immediate round of new parliamentary elections. Sargsyan flexed politically yesterday by rejecting Pashinyan’s choice to replace Gasparyan — Artak Davtyan. Despite the turmoil with the country’s generals, the military is conducting drills with 7,500 troops from March 16-20. It’s now a fight over legal precedents, constitutionality, and the (relative) rule of law: the military claims Gasparyan’s dismissal was unconstitutional and Pashinyan claims that military attempts to meddle in politics are unconstitutional. While Sargsyan exploits the formal limits of power granted to his largely ceremonial position, it’s hard to shake the expectation that Pashinyan’s recent idea of holding a referendum to pivot the country to a full-on presidential system — further concentrating executive power in the hands of whoever wins elections and undermining future scenarios such as this where the president can split the government vs. the prime minister — is his real political play. Outlast the opposition, consolidate his position since he’s still the most popular single political figure in the country, and then try to change the system.

Russian outlets are stuck watching with little insight to offer while Turkey’s government has gone to great lengths to make clear that they oppose any coup attempts in Armenia, implicitly comparing events to what took place in Turkey back in 2016 as well as likely holding out the expectation that Pashinyan is their best bet to open the border and usher in trade. Doing so would allow Turkey to further expand its economic ties with Azerbaijan and, in the longer-run, diminish (slightly) Russia’s economic role in the region. Of course, Turkey’s position mimics that of the US and EU given their own diplomatic calls on the military to respect its proper place in a democratic society. The escalating division between Sargsyan and Pashinyan, the opposition’s chance to gain more legitimacy meeting with Sargsyan as well as expressing support for the military, and the fact that Gallup polling showed 58% of Armenians wanted a snap election as of February 19 point to many potential scenarios:

Pashinyan stays in power without any election and is forced to replace Sargsyan and govern despite the fact that more Armenians (per Gallup) want him to resign than stay.

Pashinyan calls for a snap election as a compromise with the opposition and runs again.

The military more directly backs the opposition and helps the opposition remove Pashinyan.

Pashinyan stays in power, negotiates a longer timeline for an upcoming election, and tries to push for a constitutional referendum on a presidential system.

The opposition manages to force him to resign by eroding all public and institutional support without military intervention of any kind.

There are other alternatives, clearly, but the big lesson here is that Russia’s notional victory in Karabakh was a bit premature. Yes, the military will maintain close ties with Russia no matter what on logistical grounds alone if not due to personal contacts and the regional security environment. The nature of Moscow’s intervention late in the conflict, even if the opposition has directed its fury at Pashinyan, was noted by everyone. The current wave of opposition isn’t so much revanchist about reclaiming land, though Karabakh is obviously the catalyst, as it is the complete exhaustion of ideas and reform progress or efforts under Pashinyan post-2018. The failure to successfully defend Karabakh has become a symbol of the excessively high hopes held in 2018 for change when he came to power, his own rise inflected somewhat by the short and inconclusive 2016 ‘war’ over Karabakh that went nowhere. Moscow hates unstable changes in government in its neighborhood and the fact that Turkey, for its many economic failings, has more growth potential than Russia means that if one does the basic math, it’s much likelier to be able to consume any marginal increase in production in Armenia, Georgia, or Azerbaijan so long as its consumers want the products on offer. I wouldn’t write off Pashinyan, particularly if the military recognizes that throwing its weight behind the opposition forcefully would cast a long shadow from under which the country’s democratic institutions might take years to recover. And even for Moscow, winning the peace isn’t so simple as dispatching peacekeepers. But political change of some kind, either of system or of the party and individuals in power, seems fairly likely as best I can tell.

What’s going on?

Kamchatka and Magadan are requesting additional subsidy/spending support from the federal government to cover the costs of airlifting in food supplies, alcohol, and tobacco to stem further price increases for consumers. Unfortunately, the budget codex expressly bans the subsidy of transport costs for excise goods (alcohol and tobacco). Kamchatka head Vladimir Solodov and Magadan governor Sergei Nosov — the latter being properly Gogolian — have written to MinPromTorg on the matter. In Kamchatka, air transport costs about 400 rubles per kilogram of milk products, vegetables, and fruit — 80% of the production cost. The appeals rest in part on the fact that the federal government already subsidizes rail deliveries to the Far East, where food prices have often been slightly higher than the rest of the country given its dependence on internal imports i.e. production from elsewhere in the country. Food subsidies are one thing, convincing MinPromTorg and others to circumvent the budget codex for booze and cigarettes another. Subsidies for Far East transport are helping chain retailers like X5 Retail Group set aggressive expansion plans for the region towards 2023, affecting the shape of corporate competition and ability to access basic goods. The fact that the Far East enjoys that support but others dependent on air transport don’t becomes more salient when inflation picks up and incomes in remote regions are generally falling or stagnant. Subsidy pressures are expanding alongside planning pressures.

One of the beautiful things about a low base effect is that it can turn bad news into good. PwC surveys show that 76% of business respondents are expecting global GDP growth this year. Who’dathunkit?:

Orange = acceleration of growth Beige = no change Blue = slowing growth

This is of course no surprise given the vaccine rollout and now the fresh business optimism generated by the $1.9 trillion US stimulus bill. Concerns about disinformation have risen — 16% cited them last year vs. 28% this year — which reflects the politicization of information about COVID, but I’d wager becomes more applicable in contexts like Russia where there legal instruments being rolled out to suppress bad economic news. Healthcare systems was of most concern to most respondents (52%) followed by cyberattacks (47%). The 2020 PwC survey for households, however, shows that Russian consumers were more likely than the global average to be spending less in the year ahead (46% in Russia vs. 36% globally). Optimism in business tends to be exceedingly relative. I’m waiting to see the incoming survey data during full reopening/normalization in Russia to better discern how bad the damage actually is.

Businesses and banks seem to have a lot of questions and concerns about the latest round of business support promised by the government, with banks waiting for clarification from the Bank of Russia. FOT 3.0 — the third iteration of subsidized lending for businesses — is meant to be targeted at sectors and businesses that were hardest hit and thus couldn’t sustain employment. As a result, the current program is aimed at firms that took part in FOT 2.0 and are designated as the worst off per the so-called OKVED list. A business gets a fixed-rate 1-year loan at 3% interest if they maintain 90% of their workforce with the volume of money lent dependent on the size of the firm but not to exceed 500 million rubles ($6.8 million). The lending will be tracked via the Federal Tax Service’s blockchain platform and banks, led by Sber, say they’ve received 30 billion rubles' ($407.7 million) worth of applications. But banks don’t know what happens if borrowers fail to pay off the loan at higher commercial rates if they fail to save 90% of the jobs they had going into the COVID crisis. It puts huge pressure on demand-side recovery for many businesses that were worst affected, particularly if the Central Bank hikes the key rate by late April to try to tamp down inflation. Businesses are also annoyed because banks are trying to force them to become clients in order to access the loans, exploiting the federal policy as much as possible. The policy rollout will still help buoy the recovery, but I’d expect more lobbying in the weeks ahead on the conditionality of FOT 3.0.

Oil price expectations are trending higher thanks to Saudi Arabia’s call to hold off on easing production cuts till April and slow recovery for drilling activity in the US evidenced by the rig count:

VTB is recommending everyone buy shares in the oil & gas sector in Russia as the price recovery continues — a trend mirrored elsewhere where energy stocks have performed much better than many other sectors, largely due to their greater link to GDP as OECD economies enter recovery slowly but surely. The broad takeaway is that Saudi Arabia is no longer concerned about US shale drillers, which makes sense given their own need to appease their financial backers and show more spending (and drilling) discipline. But even at $70 a barrel, oil prices begin to bite into demand in major consuming economies like India because of exchange rates and the economic aftereffects of COVID as well as a recovery in gasoline prices on the US market, which will help refiners and also encourage more shale production. The conventional wisdom is that US output rises more slowly and peak demand is more likely to arrive around 2030 than now or within a few years, so there’s little to worry about. This narrative is still a bit illogical at the macro level — the US stimulus package and faster recovery is ‘crowding in’ capital that might have otherwise gone into the emerging markets that accounted for basically all marginal demand growth pre-COVID, aviation will take a longer time to recover regardless, and increasingly flexible working schemes will disrupt demand assumptions. This year looks very good for the oil sector, maybe even next year. But by 2023, the OECD might look a lot different, as will the rate of EV adoption, efficiency gains, and other related drags on end demand.

COVID Status Report

There were 9,794 new cases reported alongside 486 deaths. I’ve noticed that death figure declines haven’t quite tracked with the case decline loads and given relative success getting older Russians to isolate etc., this suggests (slightly) that the actual rates are still higher than officially reported. While COVID continues to calm down as a major story/concern in the news, it’s clear that the messaging on inflation is in reassurance mode. They’re now briefing that inflation will peak in mid-March:

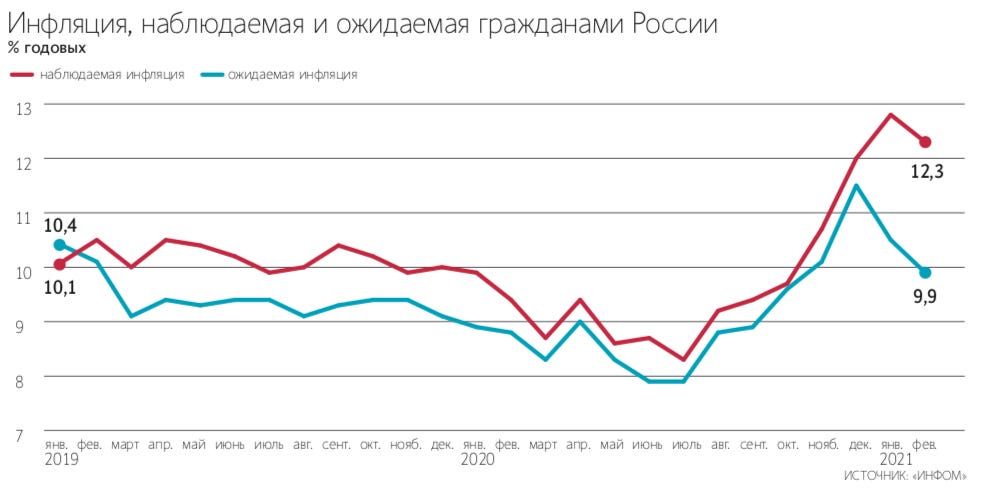

Red = observed inflation (% YoY) Blue = expected inflation (% YoY)

The Bank of Russia and economists largely agree that it’ll slow in April, which makes sense assuming the one-off price inflation factors coming into the economy via export channels ease, but much less sense for domestic sectors unless there’s a slowdown in demand. Any slowdown would mean slower growth, which then means weaker recovery. Good (not best) case scenarios show industrial output recovering to pre-crisis levels by this December — probably likely because they were weak beforehand — but the oil & gas sector lagging until 2023. There’s still a risk of 2-3 lost years, but import substitution is cushioning some of the industrial blow at least.

Будьте как дома!

Putin held court with Russia’s leading businessmen setting out a policy agenda regarding business investment across the economy. The full video’s linked here along with the published transcript. What Putin was driving at really encapsulates the direction of Russian economic policy since 2009-2010 which accelerated significantly after he returned to the presidency in 2012. The following comes after citing the 4.5% of GDP spent on economic support amid low oil prices — he neglects to mention Russia’s role in worsening that problem — and severe global headwinds:

“I want to repeat: such an active policy speaks to [our] qualitatively growing possibilities, to the decreased dependence on the global economic environment, and to the emergence of new mechanisms and instruments to support business activity.”

Translation: we are better than ever at minimizing our exposure to the global economy and achieving true economic sovereignty. Never mind that nasty bit about global price inflation. But with all of that winning aside, the aim is now to increase business investment 70% in real terms by 2030. This chart was a bit of a mess to pull together given the constant variations in Rosstat methodology per category, but I used 2014 total investment levels in current prices as the reference point and plugged in the investment % growth figures from elsewhere, plotted alongside high-tech output’s share of GDP, the growth rate for disposable incomes since 2014, and % growth for investment per capita from another dataset:

In current price terms — this is terribly imperfect, but to be frank, Russian stats are a disaster to reconstruct as it is — investment levels were only higher than 2014 in 2019 and analogous last year. Over that time, investment growth per capita only saw a significant bump for 2017-2018 when there was an expansion of retail jobs while most other sectors saw no net job creation or losses and disposable incomes only grew for 2018 and 2019, and even behind GDP — itself anemic — at that. Of course, if we go back to investment data prior to 2013, it was higher primarily due to the inflows of money into the extractive sector and greater consumer power for Russians back when real incomes were actually rising. Putin’s target of a 70% real terms increase over the next decade is akin to setting an annual increase in current prices held constant vs. 2019-2020 (not clear from the meeting) of around 6%, adjusted upwards of course for presumed GDP growth.

Putin's big claim on the infrastructure front is that federal spending rose 20% for 2020 to a princely 538 billion rubles ($7.32 billion), just barely more than the leaked volume for the new social spending package that’s since been buried by the press and a trifling sum in GDP terms given that even the promised expansion of spending from the 2018 May Decrees ($177 billion in total) fell far short of actual needs and hasn’t properly materialized so far in spending terms based on what I’ve seen:

As expected, Putin then turned to the issue of long-term reliability of return expectations on investment, always a sore subject given the adhocratic nature of regulatory fixes, changing investment agreements, and general disarray of economic institutions subject to frequent policy capture by business interests, disruptions from security elites, and a lack of coordination. Nothing substantive was offered save reference to initiatives like the SPIK contracts that everyone actually hates, but are often the only viable option available to foster FDI to localize consumer goods production. He then rambled through boilerplate on reducing costs of investment and ensuring access to financing.

What was most striking of all the statements made was highlighted by The Bell: Russia has good investment resources but “it’s better [to invest] at home, here it’s calmer and more reliable.” Bringing the positive news that Russia had decoupled more from global economic forces more to a greater extent full circle, the task now was to mobilize the country’s investment “resources” to build at home, implicitly chiding anyone thinking of funneling money into various offshore vehicles and financial assets without shoveling money into the domestic real economy. Putin’s quip about the power of home is reminiscent of Bradley Whitford’s character from Jordan Peele’s Get Out when he proudly tells Daniel Kaluuyu that he’d have voted for third Obama term if he could have — a smug note of patronizing assurance that hides a great deal of menace. In this case, the red flag is that the language of economic policy has decisively shifted to one of mobilization rather than reform or structural changes. Every commitment to improve the investment climate is couched in these terms. Mobilization always entails some degree of coercion, especially when looking at the weakness of the underlying investment data and business environment as well as the parallels to the 1980s: the situation now calls for increases of investment into productive capacity in manufacturing, particularly for key electronics components, inputs for strategic sectors including oil & gas, as well as consumer goods given the relative costs of imports keeps rising as long as real incomes fall or stagnate. And given the pitfalls of import substitution, the net production gains from each marginal ruble increase in real terms for investment levels are diminished from the lack of competition in many instances.

Andrei Guriev from Fosagro gave the initial response to Putin, and the theatrics were on full display: “Our industry, all of Russia’s big businesses, are prepared today for a genuine investment breakthrough.” I need more time to dig through this — I suspect I’ll be looking at quotes from these for awhile to come given my research interests at the moment — but it’s apparent that the regime’s business problem is only getting worse. The more they have to talk up mobilizing or making use of existing investment sources without talking about disposable incomes to foster domestic consumption or the global economic environment for exports, the more incoherent the mobilization approach becomes. CEOs and board members can make promises or assertions about their plans, but they need a demand climate domestically and externally to sustain those ambitions. One of the recurrent themes from the commentary I got through was the desire to minimize investment risks if these companies are going to invest at higher levels, which isn’t just a matter of legal certainty over contract conditions. Today’s investments serve future demand. The more the state wants to mobilize business, the more it has to provide business to sustain that mobilization. If you take the business turnover from Rosstat for innovative services and goods as a % of total services and goods produced — a leading indicator for investment efforts since they parallel efforts to raise productivity and diversify the economy — it was falling before 2019. It stood at 7.2% in 2017, 6.5% in 2018, and 5.3% in 2019. The state can’t mobilize these resources more effectively because it’s the state and the formal and informal networks of power that operate through it that are in the way of the best use of resources available across the economy in many (not all) instances. For example, a much greater degree of state spending and involvement driving infrastructure development would be a huge boon for the broader economy, but the greater role for SOEs and state procurements ends up hindering competition, innovation, and keeping costs higher for consumers while also producing suboptimal investment levels so long as the budget has to be prioritized so as to maintain large volumes of reserves.

If Putin wants business to make itself at home, then he has to instruct Mishustin to fight interest groups he can’t afford to or has no interest to take on at the moment. Calling for mobilization, even by another name, doesn’t augur a great year for Russia Inc. Putin made promises to use the National Welfare Fund to back big projects, a story that was supposed to be realized back in 2018 when the National Projects were announced. 6-year promises became 12-year promises. And business isn’t happy with the price control measures now slated to be a political priority for the foreseeable future. All happy business communities are alike and all unhappy business communities miserable in their own way. A renewed push for mobilization is sure to be common cause for grousing while smiling and thanking the Boss for the largesse the state deigns to provide.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).