Top of the Pops

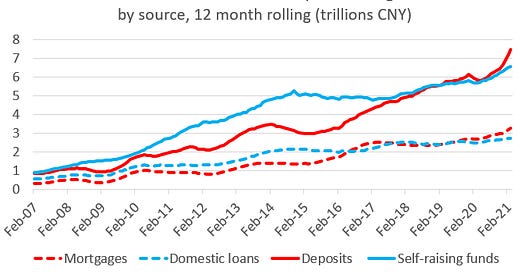

When it comes to export markets, Russia’s strongest growth bet for the year t 18 months ahead remains China. Gazprom’s renewed talk of Chinese interest in another leg of the Power of Siberia through Mongolia is a bet on Chinese demand and a reminder of the current account pressures Moscow faces with European hydrocarbon demand entering decline. IMF projections have Russia’s topline growth rate lagging the global average by about half, with China and the US doing the most lifting collectively in 2021. The greater Moscow’s dependency on Chinese demand and growth, the more exposed it is to economic contagion from its neighbor as as well as its macroeconomic policymaking. One of the big themes coming into 2021 was the need for deleveraging among developers in China. Turns out it’s not really happening:

Real estate values massively inflate China’s GDP performance on paper, propping up a great deal of securities, lending, and borrowing as well as balance sheet wealth. Rather than really slowing down the property market, pulling liquidity out of it, and pushing developers to pay down debts and hit the pause button, developers are instead using households as creditors to keep financing their activity. That’s a massive problem if households’ share of the national income doesn’t grow this and next year. The next global recession is likelier to start in China than Europe or the US, and this dynamic lies at the heart of downside risks. The “tightening” of credit to better balance growth isn’t really balancing growth and still creating a great deal of growth that’s not healthy/sustainable.

What’s going on?

Sibur and TAIF have announced that they’re merging their businesses thanks to a Sibur-led buyout, creating a petrochemical firm that would account for 70% of the domestic petchem market. The new firm would have the capacity to produce 8 million tons of polyolefin and 1.2 million tons of synthetic rubbers annually and best estimates place its equity value at $20 billion. Given the formal and informal means by which input costs are controlled, one can imagine that the new joint firm will pull its weight on pricing for procurements. What’s odd and noted in the Vedomosti reporting is that the two firms have pointedly been at odds with each other over how to expand and develop the petrochemical sector — the sense you get is that Leonid Mikhelson and those around him lobbied to push the acquisition through, which makes sense given Mikhelson’s recent entreaties over upstream assets on Yamal. There’s less money kicking around, so the consolidation of markets and rents follows based on whoever can leverage their political relationships the most effectively. It’s estimated that Sibur’s shelling out $3.5-4.5 billion to pull off the deal. Mikhelson clearly wants more.

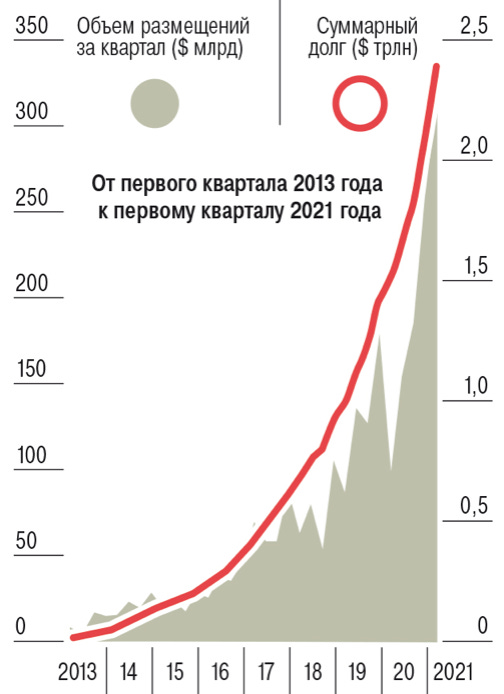

The Institute of International Finance (IIF) has a new data release out on green financing and it looks like the total volume of borrowing using green facilities globally has surpassed $2.2 trillion, with $315 billion issued in 1Q this year alone. At the current pace, 2021 issuances are set to double year-on-year. It’s expected that net issuance volume will break $3 trillion by year end:

LHS = volume issued per quarter (US$ blns) RHS = total issuance (US$ trlns)

$1.55 trillion of the net borrowing was via bond issuances, with the rest covered by loans. The US and China are leading the way. Setting aside the question of greenwashing — it’s a serious problem, but one I think that underestimates the. potential to do more even with a ‘toothless’ set of requirements — the growth rate makes alignment of financial standards for lenders more important for Russian banks, particularly since incoming carbon adjustment proposals on export markets will affect the expected profitability of exporting industries that need access to credit to sustain investment, production, or else settle accounts with counterparties. It’s another case of attempts to insulate the Russian economy from external shocks and instability falling flat in the making, and one to watch if the growth rate for green financing use picks up yet more in 2022 and onwards. Net green financing issuance domestically in Russia is a measly 186 billion rubles ($2.48 billion).

The Central Bank’s messaging, led by Nabiullina’s stark words on Friday, suggests that operating assumption that the economy is currently risking an ‘inflationary spiral.’ Bank deposit rates aren’t even matching inflation in many cases, and the current spate of price increases are eating into the value of savings. We all know that Russian politicians panic whenever savings are threatened because of their memories of the last few years of the Soviet Union, first few years of independence, and the 98’ crisis. Current inflation expectations for the next 9-12 months is 6.4% in annualized terms, a higher sustained rate than last year and based on the forecast interacting with assumed rate hikes, you’d think that few believe this inflationary wave is actually derived from the monetization of debt via the OFZ bank recycling approach that emerged last year. For January-March, Russians bought $760 million to transfer savings into USD as a hedge against ruble-denominated inflation and exchange rate fluctuations. The underlying assumption is that the 25% expansion of the money supply last year in response to COVID-19 has created pent up inflationary pressure, the problem being that the reason we’re seeing that inflationary pressure now is demand for money, not its supply, and that demand is mediated by persistent supply shortfalls mediated by seasonality, the budget’s cyclical impact on economic activity every fiscal year, the price feedback from external demand for key commodity inputs, and labor shortages.

In yet another market management measure of little practical utility that undermines the function of the market, the government is now preparing the legal basis for a ban/limits on the export of benzine. The measures would be temporary and are obviously a direct reaction to the rise in fuel prices that’s mirrored the 24ish% increase in oil price so far this year. Production is down 4.5% year-on-year in 2021, but exports are up 12.5%. On its face, a limit on exports should restore better balance to the market by reducing the impact of external pricing domestically — producers can’t markup based on export reference prices if they can’t legally export. Targeting benzine, however, is a bit short-sighted. Refiners can export component elements mixed into benzine given that the squeeze on European refiners brought on by the COVID demand shock leaves them an opening. What’s important to remember is that per another source I stumbled on (need to verify more precisely), the oil price contributes less than 10% to the end price for benzine in Russia. That makes sense insofar as refining is more about margins than absolute price levels despite there being a link between high oil prices and road fuel prices, but the odd construction of the damping mechanism for the refining sector and effect of the stop-start mineral extraction tax reforms on feedstock prices for refiners means that the supply/demand balance affected by policy matters more. Overall refining capacity was set for a strong growth year coming into 2021, but that growth requires strong external demand given the weak consumer recovery domestically. Export controls provide temporary relief, but can be gamed and will likely lose refiners money.

COVID Status Report

8,803 new cases and 356 deaths were reported. The good news is that based on the Operational Staff data, the negative trend for infection rates reversed in the last week — I’d take the data with a grain of salt, but it’s a useful trend indicator:

We’re not (yet) seeing the beginning of a sustained week-on-week increase in cases overall. I’m doubting the sustainability of the current trend because of St. Petersburg. If Moscow has leveled off (and even seen a small uptick), it’s SPB where the concerns are more obvious. The number of COVID patients coming into hospitals yesterday was up 76% week-on-week. Declines in the regions elsewhere clearly aren’t a result of the massive success of vaccinations, though the figures keep ticking up slowly. They are likely to help lower deaths and extreme cases, but they aren’t enough to prevent a huge social and economic drag on the recovery period. The renewed use of a ‘non-working’ days for May 4-7 are a straightforward measure to reduce exposure and spread at offices. The approach now is to prevent a surge, while accepting that total caseloads are likely to rise a fair bit overall in the weeks ahead though not at levels seen last year. If the % growth week-on-week figures tick past 3-5% is when real political panic sets in, I’d guess, so the aim is to contain them with limited interventions.

Trud Boys

Russian Railways’ struggle to modernize the Baikal-Amur Mainline and Trans-Siberian Railway on time and on budget has taken a darker turn. The government is now discussing reaching an agreement between RZhD, the Federal Penitentiary Service, and Mintrans to use prison labor to carry out construction works. For those who may have forgotten given the blitz of bad stories and developments since Crimea, laws were changed to allow state-owned companies to use prisoners for forced labor as of Jan. 1, 2017. Presumably there was some input from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Ministry of Justice. I’m more interested in what this development means in terms of political economy rather than just politics, though it’s a distressing example of the state’s growing reliance on the power of coercion to be able to achieve its targets. The following Rosstat data suffers from a huge discontinuity due to a methodology change around 2016-2017, which suggests we don’t necessarily have an accurate macro picture of the the underlying trends but suffice it to say they’re concerning:

The workforce is revised up by several million between 2015 and 2016, which might be accounted for through the formal recognition of informal employment and a few other measures, but is conveniently timed for political purposes. What’s odd to see, however, is that with the net increase in the size of the workforce, the % share of the employed building things actually shoots up by about 5%. That comes amid falling net investment levels across the economy and austerity policies. The post-Crimea municipal beautification projects used to create the impression that living standards weren’t, in fact, falling very likely created a fair share of local jobs, but they would still depend on aggregate budget allocations and private investment via PPPs in the long run. And what’s the deal with the large drop in value-added/refinining jobs? Some is definitional — the post-2016 data added categories for those working in IT, for instance, but that can’t fully explain it.

This is a toxic combination of factors. Pre-COVID, construction employed a growing share of the workforce despite falling investment and relative state spending levels, and now post-COVID, the hit to migration is doubling the relative pain of recovering to pre-crisis growth trends that had actually led to a large decline in real incomes. Moscow has reportedly been haranguing the Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Kazakh, and Tajik governments to ease up migration restrictions. 332,000 illegal migrant laborers prop up the sector — the data above is clearly referring to legal employment. As a result, you’d expect to see sectoral inflation because firms have to compete for labor when it’s scarce, and therefore raise wages. But that’s unacceptable in the middle of a commodity price surge, especially if it means giving any returning Central Asian migrant laborers later in the year or next year more bargaining to demand better wages, reducing the relative utility of hiring illegally to cut costs. The use of prison labor is a (re)emergent form of economic management — the costs are absorbed by the state to feed, clothe, and care for prisoners, which it does at the lowest possible cost and doesn’t have to compensate them for their labor at market rates while being able to divvy up costs with state-owned firms operating off of the state’s balance sheets.

The reduction of the prison population in Russia has been a success story for the regime over the last decade. It may be reaching its limits if the mobilization of prison labor by SOEs trying to cut costs and reduce the burden for the budget is normalized as a policy tool to address the current ‘inflationary spiral.’ Demographic decline is a frequently overstated and misrepresented challenge for the regime’s long-term prospects. Far more worrisome than the current rate of population growth is what happens to the labor market when labor becomes more relatively scarce, productivity-enhancing investment is lacking, and the economic activity that’s gone ahead since 2013-2014 may in some cases be more labor-intensive. Construction is a great example. If Putin seriously wants to increase the net area of new builds constructed annually by 50%, they either need more people or need to automate a large share of existing construction activity. There’s a hard limit to what the latter can accomplish, so they’ll still need a lot more workers. Central Asia won’t be as readily able to offset in the current environment. In the last 10 years, the working age % of the population has dropped by about 5%:

The tick up in 2020 likely reflects some of the mortality data as well, to be grim about it. When you look at net migration figures rather than gross flows of migrants from the CIS, the net immigrant population in a given year accounts for 0.2-0.4% of the working aged population. It’s significant and crucial for a wide array of low wage industries that help keep the economy together, but the emigration data almost certainly reflects Russians who are more educated, have more savings, and/or more international opportunities to leave in the first place. The combined effect is to lose more educated labor that the regime wants to fill higher-paying jobs that help sustain the balance of tax transfers into the social safety net given the low ratio of workers to retirees. It also goes to show how disruptions to key links in the system of sectoral balances the regime has built up interact with the mismanagement of inflation, fiscal policy, and investment. There’s a balancing act to repression in Russia. You hold fewer people in prison to decrease the points of contact for more of the country with the system of incarceration while increasing the ‘soft touch’ forms of repression like short-term detainments and fines, a system that becomes more important the worse the economy becomes. But once you start deploying incarcerated labor to manage labor shortfalls for nationally significant projects and head off upwards wage pressures, the political logic of maintaining labor that can be coerced ends up being reinforced in a self-sustaining, unvirtous spiral. Unless real incomes significantly grow, even low levels of price inflation pose serious risks to savings. The higher the Central Bank hikes the key rate, the more expensive private capital to finance construction of the country’s sorely needed infrastructure becomes.

This remains speculative insofar as migrant flows may well recover more normally next year. There may be a turn away from prison labor, though I’d guess that would instead be replaced with military labor (at least for railways). As the labor force shrinks in size, the Kremlin has to square its employment stability mandate with wage pressures. The only way to prevent inflation in a ‘normal’ economy in the labor context is to leave a significant degree of slack i.e. running the economy below potential, weakening demand and growth. But Russia’s already doing that while trying to eradicate poverty in absolute terms, primarily through employment which then supports social transfers. The only way to repress wage inflation given the country’s current demographic outlook if maintaining some form of full employment is the political priority, being able to mobilize labor for state ends matters more over time. We’ll see if Central Asian governments play hardball if they realize the extent of the problem Moscow faces alongside their own woes.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).