The Center Cannot Hold

The CSTO's been proven impotent, and Russia it seems may be too more than ever

Top of the Pops

US sanctions have started to hit Minsk’s wallet — Belarusian authorities are reportedly having a hard time selling petroleum products abroad according to reporting from Argus cited by finanz.ru. The new sanctions push from the EU and US has forced Lukashenko to look to Russia for foreign financing needs instead of trying to use western financial markets since there’s now growing uncertainty both about future sanctions risks as well as dollar and Euro earnings. On Saturday, it was reported by RBK that Belarus is now planning to issue 100 billon rubles ($1.36 billion) in Eurobonds in Russia for 2021-2023 to meet its funding requirements just after Fitch gave the country a “B” credit rating with a negative outlook:

Belarus’ domestic financial markets are too small to be of much help financing deficits or budgetary needs that are amplified by interruptions to foreign currency earnings on exports. It can’t comfortably replicate Russia’s use of its state banks to recycle foreign earnings and manage the monetization of debt. Finance minister Yuri Seliverstov appears confident that there are enough reserves that have been built up over previous years to get through the current funding/financing cycle without any problems. The budget deficit was 1.502 billion Belarusian rubles ($597 million) for 1Q, a record. Since refined products, normally one of the drivers for economic recovery at a moment like this, are under sanction, it seems likelier that large deficits will persist in the year ahead. By no means is that necessarily unsustainable, but the the bond issuance hints at deepening financial integration with Russia by default. Gold and currency reserves are tilting back up, likely driven by rising commodity prices lifting exports like potash, but since December, domestic price inflation has hit 4.6% with no signs of letting up. Employers claim they’re cumulatively 83,800 workers short — I’d watch this given the disastrous response to COVID and very limited opportunities to import labor. Higher inflation hurts doubly if export earnings don’t find a way around the latest sanctions pressures.

Around the horn

On May 14, reports that Azeri troops were advancing into Armenian territory around the lake of Sev Lich in the Syunik region triggered an immediate political mini-crisis as Yerevan reacted. The lake is divided between both countries by the de jury border, and Azerbaijan appears to have been using troops to try and fully seize it. Ara Aivazian, the acting foreign minister of Armenia, immediately consulted with CSTO Secretary General Stanislav Zas to try and bring Moscow to pressure Baku to stand down. After an initial pullback, Baku has now ordered military exercises with 15,000 troops running though May 20 in an obvious show of military preparedness. Aliyev timed the provocations quite deliberately — the Armenian parliament failed to name Pashinyan prime minister for the second time in a row on May 10 and, as per the norm in many former Soviet parliamentary systems, parliament was dissolved. It also coincided with turnover staffing the Russians’ peacekeeping mission — Lieutenant General Aleksei Avdeev assumed command on the 14th, the day after things kicked off. The “borderization” of the conflict whereby Aliyev deploys these provocations to his own benefit undermines any confidence in talks about connectivity issues. But it’s also hard to see those efforts being abandoned or rowed back because of the terrible position Armenia is in economically and the fact that they can reduce the net cost of absorbing Karabakh for the regime in Baku. What’s more, it’s unclear what role, if any, the CSTO really has in managing the situation since at this point it’s the bilateral influence of the Russian and Turkish missions now stuck reacting to what Aliyev initiates while Armenia waits for the elections to play out. Moscow certainly doesn’t want this headache right now. We won’t have any clarity on what to expect from Yerevan till the elections settle what parliament looks like.

I highly, highly recommend following Eurasianet’s updates on the status of vaccination efforts and COVID cases in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. The following is a useful snapshot of the current state-of-play with 7-day averages, noting of course that much of this is affected by testing capacity and the usual trouble with official numbers we’ve seen in Russia:

Kazakhstan’s higher numbers likely reflect the higher levels of resources thrown at care facilities and testing from the earlier stages of the pandemic. The information about doses administered is, broadly, spotty at best, but Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan are clearly in the lead on that front. Sputnik-V, Sinopharm, AstraZeneca, local outputs like Qazvac in Kazakhstan, and other vaccines from Russia and China are all being put to use. My question is how long it takes to get to collective immunity since a prolonged vaccination period increases risks of mutations and, more importantly, imposes a drag on recovery given how much of the region’s output is labor-intensive or, in the case of countries like Georgia, heavily dependent on the confidence of tourists or nationals consuming services. The demographic and political impact of the virus on development arcs, however, isn’t obvious. Kazakhstan may well see record births this year, for instance. It’ll realistically be some time before we have a fuller statistical and political account of what the mortality rates induced by COVID or COVID-related shortages of proper care or resources did across Eurasia. But the rates of vaccination we’re seeing are, on the whole, quite worrying.

The circus in Kyiv continues as the Ministers of Economic Development, Trade, and Agriculture and Infrastructure — Igor’ Petrashko and Vladislav Kriklii — have left their posts voluntarily and health minister Maksim Stepanov was relieved of his post. The dismissals come after another quarter of economic contraction —2% of GDP — and a drawn out process securing access to vaccines after the rejection of Sputnik-V. Pfizer/Biotech are expected to supply 473,000 doses through the COVAX scheme in the latest development. These announcements come just after the decision was taken to charge Viktor Medvedchuk, friend of Vladimir Putin who happens to be the godfather to Medvedchuk’s daughter, with treason. All told, Zelensky is continuing his full-court press with Washington — his talks with Secretary of State Anthony Blinken last week were designed to fashion a political narrative that he’s waging a war against corrupt oligarchs, embodied by figures like Kolomoisky and Medvedchuk, to stabilize the country’s prospects while also managing the threat from Russia. The political lobbying is smart. If Zelensky wants to clear the next IMF tranche, Washington’s the most important institutional player within the IMF to help since it now has to till the end of June to meet conditions. I’m not a Ukraine specialist so I don’t want to get too far ahead of myself, but I think Zelensky’s tack is a source of immense frustration for the Kremlin because for all his flaws and the struggles facing his party Sluga Naroda (its polling lead is relatively small but with an active voting base), Zelensky has figured out how to appeal to Brussels, Berlin, Paris, and Washington while thinking creatively and independently. Offering talks with Putin completely wrong footed the escalation narrative that Russia and Russian outlets wanted to push to convince people Kyiv was to blame. Further, offering Medvedchuk in exchange for Ukranian POWs is both great political theater and also a useful sign for foreign capitals that have been skeptical of Ukrainian reform efforts after Yatseniuk quit and saw early efforts come to a grinding halt. It’s the deployment of geopolitical trolling, but in service of solidifying some kind of public support for what looks like a slowly expanding effort to target individuals (in a politically self-serving way, of course) that do probably pose massive roadblocks to reform efforts as well as showing the West there’s still ‘life’ in the effort. The problem is keeping it up. These tactics create an escalatory logic similar to Russian media’s domestic efforts whereby the only way to keep generating the same effect is to raise the stakes. I’ve got no insight as to who will replace the ministers now leaving government, but Zelensky’s approach seems likely to lead to more arrests and trigger fights over the redistribution of assets and rents to elites friendlier to Zelensky’s program.

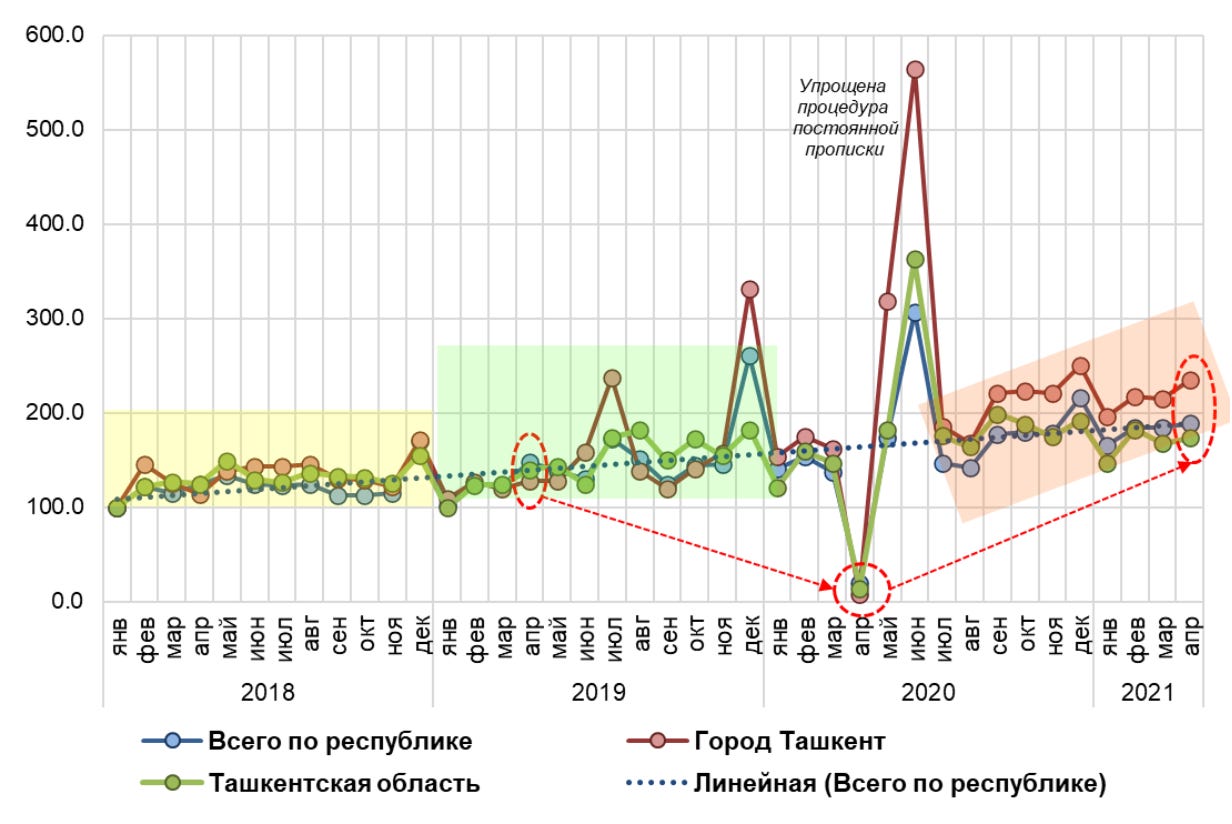

Uzbekistan’s property market appears to have returned to long-term trends with record levels of deals, but experts aren’t expecting large increases in prices yet. In April, about 20,800 real estate deals were made — a 2.5% increase over March. The lesson here is that the construction of credit subsidies matters a great deal, as does the relative level of wealth inequality before such stimulus measures were taken. In Uzbekistan, mortgage subsidies were targeted at poor families and the new system in place is primarily aimed at offering discounts on the initial principal paid rather than a very low mortgage interest rate. Subsidized credits were targeted at the construction sector, which unlike Russia doesn’t have a problem ensuring adequate labor levels since it benefited from limited migration and enjoys a much younger labor force in a country with a growing population. The following index shows the volume of deals:

Blue Sold = entire republic Red = Tashkent Green = Tashkent region Blue dotted = trend line (entire republic)

The result is that unlike Russia, there’s not the same supply-demand imbalance, also aided by the fact that Uzbekistan has actually grown since 2014 and real incomes have as well. There wasn’t the same rush into the secondary housing market either since the relative wealth gap in the country isn’t the same as Moscow (and to a lesser extent Piter) vs. the rest, though wealth inequality is obviously a huge problem when you dig into what state officials and the richest businessmen own etc.

The Post-Post-Soviet Order and Supply Chain Crunch

In the wake of the border conflict between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, observers had a perfectly good question: where the **** was Russia!? Astana jumped into the breach diplomatically faster than Moscow by initial appearances, with Moscow aping Tokaev’s line the day after with a bland call for talks between both sides. The only evidence of higher-level engagement afterwards came with the extension of a Victory Day parade invitation to Tajik president Emomali Rakhmon. What’s all the more telling is that four days later, China hosted both countries’ ministers of foreign affairs for talks in X’ian about the situation on the border. Japarov, it appears, didn’t want to come to Moscow and agreed to meet with Putin later in May to discuss the situation in Moscow. The diplomatic process still relies on Moscow as its “epicenter” but Russia no longer controls the course of diplomacy.

The dual crises recently facing the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) in the last month — first the Tajik-Kyrgyz border conflict and then last week’s Azeri push into Armenian territory — have shown that it’s incapable of sustainably regulating border/frozen conflicts in the region because of Moscow’s underinvestment into the organization as a formal institution. These types of conflicts analogously appear between Greece and Turkey, both NATO members, constantly but the US and other European partners immediately step in to contain the problem and find solutions. The CSTO has none to offer to Armenia or Kyrgyzstan respectively, at least based on what we’ve seen from the diplomatic process thus far. Less predictable reactions in Ankara, Moscow, Astana, Beijing, and so on dictate ad hoc political responses meant to tamp down tensions instead of long-standing institutional arrangements trusted and observed by member states for conflict resolution. The grouping has become a vector for lobbying in Moscow more than a serious security institution — Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin is now proposing that the CSTO’s parliamentary assembly hold talks to coordinate activities regulating the internet. His priorities after last week speak volumes, all the more stark as the United States has begun the withdrawal process and on May 8, a bomb attack outside of Kabul killed at least 68 and injured 165 people. You’d think the CSTO would want to start messaging a formal role for border and conflict management, particularly since Tajikistan and Uzbekistan aren’t hosting US military bases for now. China’s nervous as well about the incoming wave of political instability.

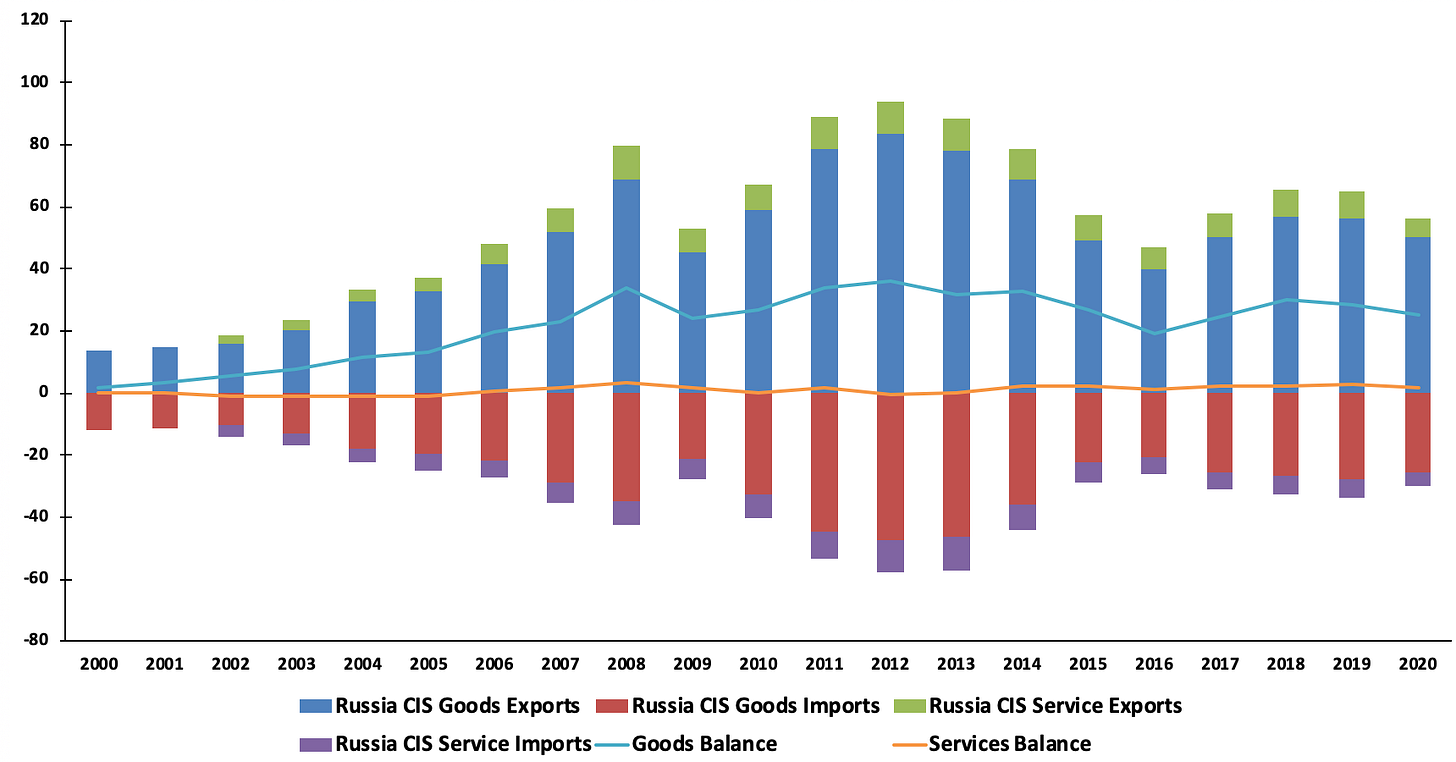

These events may be linked to a qualitative change in the political calculations of Eurasian elites after the annexation of Crimea and war in Donbas and also reflect the balance of economic power that had begun shifting before 2013, but became more visible with Russia’s stagnation. The structure of the Russian economy vs. the sources of growth in Eurasia’s economies — export-sectors dominated by resource extraction or cultivation — tell a fair bit of the tale since it’s easy to grasp that China’s voracious appetite for natural resources had shifted the economic gravity of Eurasia’s exports by the late 2000s. Russian oil diplomacy during Putin’s first 2 terms regarding the ESPO pipeline and eventual branch built to link to Daqing reflect that. The following is in USD blns:

Russia views the CIS as a dumping ground for its goods exports — Chinese and European consumers rarely want to swap other quality brands with Russian output — and runs a neutral trade balance when it comes to services i.e. intangible products. Given that Central Asia and Azerbaijan grow primarily based off their resource/goods exports, Russia’s persistent goods surplus reflects their inability to use the Russian market and the EAEU as a vehicle to sustain diversification since Russians are less likely to be as fussed about branding, particularly if, say, a firm in Kazakhstan partner with a Russian one or else Russian firms are ale to utilize FDI to realize lower labor costs or other comparative advantages on markets within the EAEU customs area. The problem, of course, is that Russia’s persistent trade surplus means, in practice, that Russian elites benefit from the accumulation of earnings/rents in bilateral trade in ways that elites in Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan have a much harder time doing. As I’ve argued before, the stagnation crisis that hit Russia in 2013 was a former Soviet Eurasian epiphenomenon — resources were increasingly ineffective to deliver growth, and therefore create new rents. Enter transit and the Belt and Road Initiative.

The post-post-Soviet order isn’t a new thing so much as a reflection of underlying realities facing elites in Eurasia that have come to a head during the COVID crisis in the wake of Crimea and multiple oil market shocks. The only way to break this impasse for Eurasian elites is for Europe and China to consumer imported goods and resources, a spotty and uneven political proposition given their respective political economies and policy approaches to recovery. Transit was long the geopolitical and market ‘meme’ to justify the bullish case for Kazakhstan and Central Asia’s economic prospects. The expansion of physical infrastructure linking the region to Europe and China would open up opportunities for exports, FDI, and more. None of that has been particularly borne out by data thus far, but the current inflationary wave across the global economy is driven by a massive crunch on supply chains. To go back to Odd Lots, I’d recommend the latest with Ryan Petersen who covers just how bad the bottlenecks are. If in normal times something like 8ish% of deliveries are delayed — a complex interaction of available shipping capacity oversubscribing its capacity for cargo based on assumed canceled orders, rerouted deliveries, and so on — 30% of container ships are now not making their delivery schedule and 37% of containers are getting bumped from any given shipment because priority goes to previously subscribed logistical capacity. The massively sustained demand for goods during lockdowns has run into the shipping industry throttling down capacity expecting consumers to spend less and the effects of stimulus efforts, particularly in the US and now slightly stronger Chinese consumer activity, are stretching logistical capacity to the limit. You’d think that this would be Kazakhstan and Russia’s time to shine as rail transsiphments between China and Europe could scramble to make up some of the slack. After all, Europe still sends lots of empty containers back to China.

The fact is it’s had little appreciably positive impact for the region, or for China for that matter, especially since it feeds into domestic price inflation. I dug around a bit and found nothing of note for material gains that will last beyond the current crunch. The Kazakh government in early March ordered a halt to truck traffic with China to free up more capacity for trains, which just reinforces that it’s got its own bottlenecks and is forced to prioritize. Maersk China Ltd. managing director Jens Eskelund is warning that the subsidy levels remain crazy high and aren’t sustainable despite the many commentators a few years back confidently asserting these routes would pay for themselves in time, that subsidies would actually be rolled back, and that they serve a useful function regardless of the structural problems of domestic consumption levels in Europe and China. I’m not saying you shouldn’t build more railways, but they’d be a hell of a lot more useful if Russia consumed more. One of the few drivers of increased Eurasian railfreight aside from macro factors is actually Brexit — DHL is now running trains from X’ian to Kaliningrad via Kazakhstan to avoid the additional administrative lags and paperwork costs within the EU to export to the UK. Still, this is DHL reaping the benefits of regional rail subsidies which we have no real clarity on from good quality data sources. The post-post-Soviet order is really about the exhaustion of growth to create new rents, desperation to find new ones, and failure to create durable institutional models with external powers to regulate conflicts ably. Moscow’s still got huge stakes and ties with all of the relevant governments, major institutions, and so on, but the increasingly brittle governing structures in Moscow now laser-focused on addressing domestic political and economic problems have limited scope to handle these more recent crises. It’s a crisis of structural power.

Structural power is precisely about what’s latent, unstated, even invisible until it’s tested. It’s an understanding of power that clashes with the more conventional metrics that rely on “projection.” Military bases, peacekeepers, a nuclear arsenal and the like. But structural power is also about institutions and institutional arrangements, even ones that are market-led. The CSTO has proven irrelevant to crisis management in the last month, China has no institutional structure in mind for BRI in Eurasia outside of relatively weak customs agreements, and elites are still stuck figuring out where they can wring rents from. Diversification plays that role in these contexts generally, just as it is in the Gulf states. Robert Gilpin’s chief insight into hegemony was that the economic and political costs of hegemony accumulate over time, forcing the hegemon to do more to adjust to those costs domestically or else try to shunt those costs of adjustment onto partners or rivals. The same logic applies to declining powers trying to preserve their status. They’re doing more and more to maintain parity, at least psychologically, if not less and less over time. Those annoyed by the “Russia is a declining power” argument tend to dismiss it too lightly because its proponents are rarely area experts and rather hold emeritus positions in the Washington School of Armchair Strategy. They’re right, but for the wrong reasons and make cookie-cutter arguments intended to win them plaudits with administrations. The post-post-Soviet order is a crisis of institutions and elites amid economic stagnation and a changing regional order wherein no new power is yet emerging that can provide an adequate source of export-led growth, investment to sustain, diversify, and increase domestic consumption, or reliable institutions. That has Russia’s decline written all over it the more hollow its institutional presence becomes and dependence on personalist politicking deepens. Without a return to the Iran Deal on the part of the US, I have no idea what’s going to provide a positive outlet for growth ahead. Resource won’t do it, nor will Russia, China, or the EU at this rate.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).