Top of the Pops

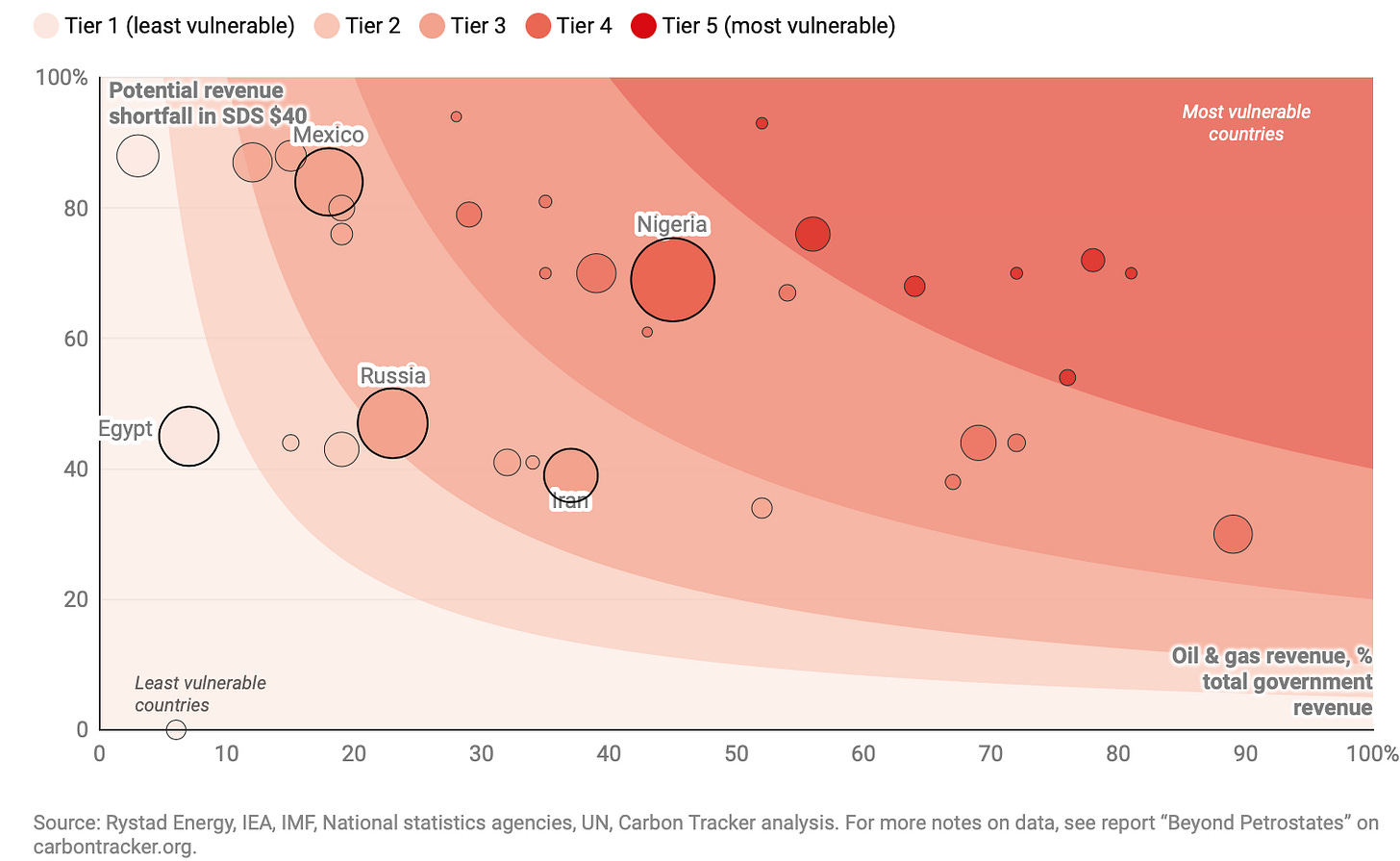

The energy transition think tank Carbon Tracker has put out a quick-hit post on how petrostates stand to lose a collective $9 trillion in fiscal revenues over the next 20 years assuming a low carbon scenario. The kicker? It’s mostly lower prices doing the work. The report’s a great starting point, but it’s actually far too limited in scope to capture the extent of risks as well as how those changes manifest unevenly across petrostates because, unlike the basic models used here, these changes are dynamic and crucially entail differential costs of production, transportation, and soon carbon adjustment to different export markets. The following is Carbon Tracker’s identification of the 19 petrostates covered by tiers of vulnerability:

First off, Russia’s vulnerability is probably misrepresented here. The actual threat isn’t fiscal, it’s macroeconomic and across the real economy. Moscow has proven that it’s willing to steadily increase the debt burden on consumption, the general public, and even oil & gas companies as needed to increase its tax intake. The problem is more that in doing so, growth outside of the oil & gas sector is harmed, a growing amount of economic activity is cross-subsidized through the oil & gas sector, particularly in the Arctic or through “buy Russian” provisions for tankers and ships often meant for the Northern Sea Route, and a diminished current account surplus creates pressure on monetary policy over time (as seen this last year when the key rate cut worsened mass cash withdrawals from banks). There’s also the issue of what, in this scenario, will be the cumulative loss of tens of billions of dollars’ worth of remittances over time, creating instability elsewhere. But the problem ultimately is that as prices stay lower for longer and demand begins to fall, marginal producers unable to adjust output and those facing higher sunk costs — whether they be direct subsidies, fiscal exemptions, and/or directly higher costs due to geography, geology, and climate — will slowly cede ground (assuming reserve replacement doesn’t fall off a cliff across the Middle East). So in actuality, yes, a country like Saudi Arabia would lose large volumes of revenues in dollar terms and yes, prices will be lower, but as demand declines, the relative size of the cartel able to control prices will shrink as will the footprint of private firms operating in the space until it’s mostly privately-held drillers that are much less likely to be vertically integrated. Perversely, that means that greater price stability may eventually come once oil is no longer a driver for road fuel demand, and also that the fiscal losses for Russia and other similar producers are actually under-stated because of the capital costs of maintaining output. Eventually, the messaging around the energy transition is going to have to get properly geopolitical and engage with more than just the collective action problem of emissions, but things like this piece from Carbon Trackers are a useful starting point to have that discussion.

What’s going on?

MinEnergo now expects coal exports to the Asia-Pacific to rise by 42% over 2020 levels through 2025, reaching 174 million tons. Rising demand on the Indian Ocean rim is a big part of what looks like Russia’s “new-look” export strategy as it adjusts to the reality that coal for thermal power generation is dying (relatively) quickly in Europe. But the mismatch between the logistical costs of coal exports and the relative earnings are massive. Coal accounts for as much as 40% of Russian Railways’ haulage, but only 4% of export earnings and the lowest tariff schedules for the rail monopolist. Russian coalers have to put it all on developing economies in the Asia-Pacific to sustain price levels, since anything under $60 a ton — we saw prices go lower during the worst of COVID — renders any pure play producers who don’t own rail wagons or port infrastructure unprofitable. Prices will undoubtedly fluctuate since green energy, retrofits, and so on are going to raise steel demand, but thermal coal for power faces some wild, unstable pricing ahead. The other issue is that coal demand tracks closely with global GDP growth and recovery, which are a source of massive uncertainty at the moment.

It’s expected that restaurants won’t return to 2019 levels anytime this year based on the latest data available. The current lifting of restrictions in Moscow is expected to return restaurant activity to where it was in September 2020, taking in about 850 million rubles ($11.53 million) in turnover but there’s a huge question mark there. How much of this is really just pent up demand that’ll run out fairly quickly?

Title: Restaurants opened in 2020 by type of cuisine, %

Descending: “Author’s cuisine” i.e. chef-centric, Asian, Italian, Grill and meat (steakhouse equivalent), Seafood, Georgian, European, Vegetarian/healthy, Russian, rest (bars, hookah bars, karaoke, coffeehouses)

Closures of restaurants in Moscow last year rose by 35% over 2019, mostly due to disagreements over rent despite ostensible policy support. That translates into a lot of service job losses that’ll persist through 2021 across the country. The Federation of Restaurateurs and Hoteliers estimates 40% of business owners in the sector lost their businesses last year. Many of these businesses had problems prior to the pandemic, so the hit is not necessarily as bad as it looks, except that suggests that consumer demand really is a glaring problem that Russian policy has done nothing to address thus far. Recovery will happen, but it seems it’ll be drawn out.

The government and presidential administration are back to reviewing bankruptcy reform that was first launched in late 2019, but then dropped in March 2020 as the pandemic overtook all other policy considerations. The main aim has been to change the legal regime such that debtors have an easier time restructuring to be able to repay their debts when they declare bankruptcy. MinEkonomiki is pushing this line to change the current system that first leads to an initial custodial period where balance sheets and a company’s health are reviewed before the creditor then calls in what’s owed with limited chances for debtors in bankruptcy to escape. Lawyers and arbitrage organizations are pushing back on the initial proposal concerned that, as written, it’ll impinge on creditors’ rights and weaken the quality of administration for a given debtors’ assets when a bankruptcy case is being heard by the courts. It’s quite telling that bankruptcy reform matters so much now as support measures roll back and many should expect lopsided losses from the earlier stages of recovery. The details honestly aren’t that important. What matters is the populist pressure to give SMEs and the growing number of indebted Russians more room to breathe vs. the interests of asset owners who’ve benefited from years of economic and political consolidation and, during COVID, record low interest rates. This story is mostly technocratic, but the timing of the policy debate is what caught my eye.

Vice Minister Victoria Abramchenko appears to have stepped in it as she’s written a letter to MinFin, MinEkonomiki, MinPrirody, MinPromTorg, and MinEnergo asking that they work out how to make use of the “ecological payments” now mandated for polluting industries and firms for spending initiatives meant to liquidate dirty assets whose owners are either bankrupt or unknown. It’s immediately clear from Kommersant’s reportage that no one wants her idea to come to pass because of the political implications. No one wants another journalistic investigation digging up a beneficial owner for something terribly dirty and showing it publicly, thus forcing the state to remand property otherwise held by someone who’s friendly with the regime. Similarly, no one wants to let any other agency get their hands on that flow of money meant to be assigned to the purpose since suddenly the ministry empowered to carry out this policy would have a lot more coercive power to be used and to pursue agendas. MinFin’s selling that this idea is anathema for the principle of budget stability. Abramchenko got nowhere with this idea more broadly last year when it seemed to imply that budget funds would be used to compensate SOEs and large firms for the closure of dirty assets. This is policy entrepreneurship 101. It’s a collective inaction problem, one where no one wants to upset the balance of delegated power, especially since any such program is going to end up paying out the country’s dirtiest firms, which would be a political landmine with the public after the last few years of local protest activity entirely distinct from the likes of Navalny and the non-systemic opposition focused on national politics.

COVID Status Report

Infections ticked up slightly to 15,083 new cases with the death toll rising to 553. The underlying data and reporting from the Moscow Times confirms my suspicions about the data we have, but doesn’t entirely rule out an impact from the vaccination launch as is. Jake Cordell notes here just how slow the rollout actually is if we assume Moscow’s by far the best equipped logistically. Note that 2.2 million have gotten at least single dose thus far, 1.7 million have gotten both which puts the national total at just 1.5% of the population :

Russia’s wildly overselling its success, but there are enough vaccines going around to marginally affect infection rates. This would mean that most of the decline observed is behavioral, but we’d then expect the numbers to reverse if places are opened up. Yet regional health data suggests a falling number of cots assigned to COVID patients and so on. So what gives? The Kremlin’s even ruled out trying to offer payment or other inducements to get people to get the vaccine. This suggests that there’s definitely systemic tampering with the infection and death data, but that a national decline is happening as a result of successful public health measures, changes in behavior, and possibly (in some instances) a degree of herd immunity (though I’m quite skeptical of it, especially since Russian authorities have played up counting people who’ve been infected as deserving of a potential COVID passport). Getting it under control really matters, especially when places like Urdmurtia and Chechnya are rolling back mask requirements too early. The Far East is taking a big hit from China’s ban on frozen fish imports from Russia. You’d think they’d realize that a slightly greater degree of transparency would actually foster more trust in many instances.

Adjust if you must

Carbon futures in the EU are on the rise, breaking 40 euros per ton for the first time ever in their history, an over 20% rise just for January and early February:

This is huge price movement and lends credence to hedge fund theses that prices would rip up this year. The timing is also perfect since it coincides with what is now a new emerging commodity super cycle (they've historically followed roughly 12-year trends and segments, though the math can get fuzzier for oil the last two decades):

But unlike the last super-cycle period when the EU’s emissions trading system launched (towards the back-end of the commodity rally), carbon prices are now set to rise in tandem with commodity prices. That’s a massive difference to consider, even if it’s just a European phenomenon at the moment. As carbon futures trade higher — and become a more attractive medium-term commodity to hedge with — they amplify the price inflation effect of marginal increases in commodity prices for producing firms. That then accelerates their interest in improving energy efficiency and decarbonizing supply chains. US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told the Senate Finance Committee that president Biden fully supports carbon pricing, though it’s definitely not the priority at the moment. Things are moving quickly on this front. As Daniel Gabor lamented (to my small joy as a lower case patriot abroad):

Russian firm EN+ Group is the only big player I’ve seen step out and set a net zero target for 2050 with a 35% emissions reduction target for 2030. The issue is how that net zero strategy fits into the national approach to energy intensity and supporting policy mechanisms for companies to make that leap. The base scenario internally seems to be a 9% reduction in energy intensity by 2030 that accelerates afterwards. But this is a really early stage policy target that I think is soft, and while difficult to achieve with the current fiscal and energy policy framework, might end up being more feasible than expected. Sakhalin is experimenting with its own emissions trading system apparently modeled on others like that found in Europe. It’s currently being worked out, but my guess is that the foreign firms still operating on Sakhalin approached Rosneft and Gazprom on the matter since they wanted to mollify investors and were willing to help front some of the costs it entailed.

Until an actual system is agreed upon, there’s not too much point in riddling over what to expect. Those discussions are completely opaque. But if Russia sees a pathway to establishing a cap-and-trade system — I’d guess industries would lobby heavily to set emissions reference levels that would meet Paris agreement targets without significantly reducing emissions further — it’ll be a significant step away from its otherwise all-encompassing turn towards sovereignty in economic and political matters. Climate change, by definition, cannot be addressed by sovereign states on their own individual terms. It affects everyone unequally at great cost. Unlike the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union, a carbon trading scheme has to have some immediate degree of interoperability or integration with whatever’s developed in Europe and China if Russian firms seeking to export any kind of good don’t want to either lose market access or else have to sell at an effective discount against competitors, especially when the domestic market is so unattractive for demand. It can’t be a distinct competitive model because, unlike the EAEU, it has to achieve concrete policy aims and fast.

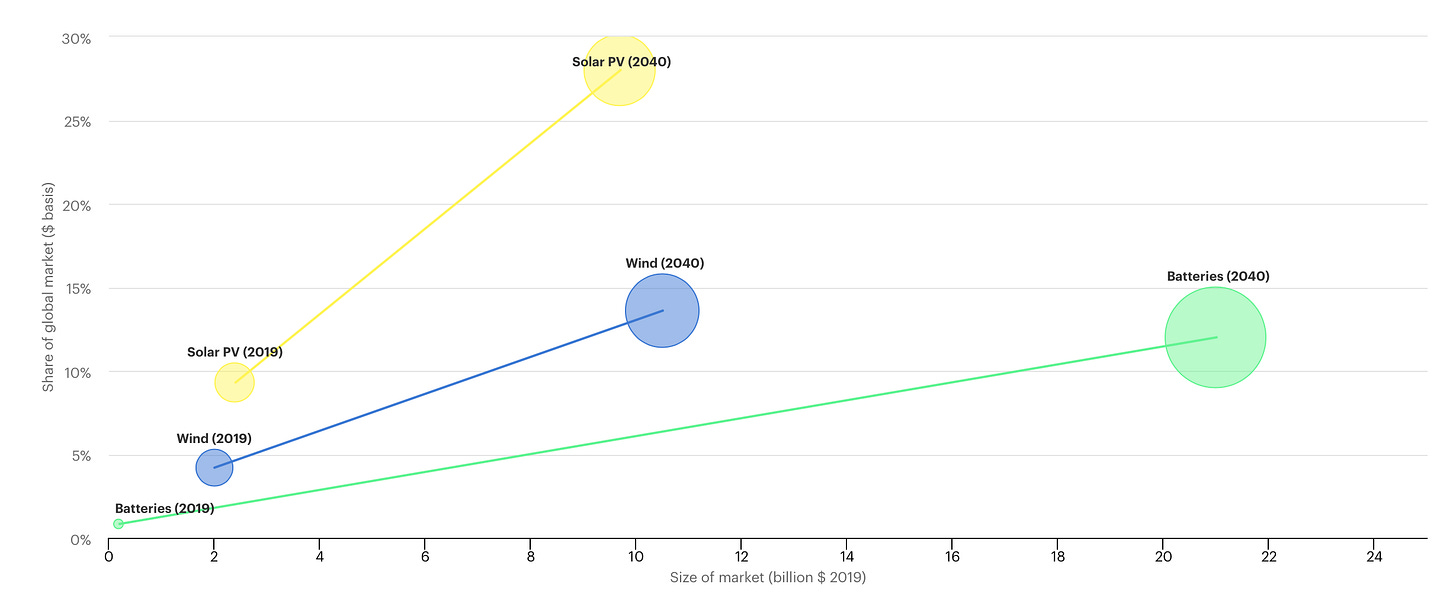

Given the embedded problem of sovereignty vs. international competitive regulatory and normative pressures baked into the adoption of carbon emissions trading schemes, the next decade that EN+ is focusing on will also see a related geopolitical shift. India is expected to overtake the EU as the world’s third-largest energy consumer by 2030. It’s share of green energy tech markets will rise bigly in parallel per the IEA forecast. Lhs is % global market share vs. x-axis of US$ blns:

In much the same way Russia is ultimately a price-taker on world oil markets because it can’t ramp up production or idle production cheaply (setting aside breakeven and infrastructure costs), it’s now going to be a carbon price taker on world markets as they evolve. India’s a fascinating case since its loved to exploit the incredibly lenient tariff boundaries it negotiated for during the talks that led to the WTO’s creation as a protectionist measure, and it’s long been a pain to deal with on trade issues and carbon is fast becoming one. I don’t have much insight to offer here on it save to say that there is no longer any room for a regulatory race to the bottom once carbon prices in Europe climb high and companies show they can manage them effectively as competitors cut costs. The EU might apply a carbon border adjustment as soon as this summer with trade partners while China’s move to an emissions quota and cap system will most likely hurt Russia’s coal exporters sooner rather than later. In Russia, it’s estimated that about 20% of emissions come from transport, so it’s not actually road fuel, but the decarbonization of the power system for industry and heating that’s really going to be the test of success.

The real problem for Russian policymakers is that oil & gas producers might absorb marginal price increases for carbon-adjusted exports while selling at a cheaper domestic price, which would lower consumer price inflation, but disincentivize energy efficiency gains and fuel switching. But metallurgical firms making money exporting steel, aluminum, and other refined metals can’t really take that same approach, especially if carbon border adjustments eventually take supply chains into account. The higher export price would feed into the sale price for domestic consumers of steel. Construction would get that much more expensive. This is the dynamic we’ve seen with agricultural commodity exports and domestic inflation, and export quotas and differential export duties set against a base price don’t really work. Carbon adjustment is essentially a systemic inflationary risk for Russia, either through bidding up of prices to match international market rates or, taking from the command economy elements of Russia’s economic governance, through the existence of shortages due to a lack of sector profitability and therefore inadequate investment into production (which eventually creates more dramatic bursts of inflation after being managed for a time). The more expensive carbon gets in Europe, the more likely Russian firms have to adjustment seriously. In fits and starts, these policy initiatives do seem to be making progress, even in Russia.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).