Top of the Pops

First, adding onto yesterday’s column on transnational sources of emissions. Shipping emissions are rising despite the new rules changes to mandate the use of cleaner-burning fuel oils and scrubbers, and it’s basically matching Germany and France’s combined emissions:

Second, Tesla, Uber, and leading power-generation firms like Southern Company in the US are preparing to lobby hard for the Biden administration to set a 2030 cutoff for the sale of ICE vehicles. Executive action can push forward things like emissions limits, but it’s going to take congressional action to support investment into relevant infrastructure, provide tax credits for people trading in legacy vehicles, and more. I wouldn’t be surprised if those interested shift dark money into the Georgia races, but it’s possible they’d be able to lobby and turn 1-2 Republican senators who have more leeway to break party ranks, especially since Republicans are going to want to make Michigan competitive again so long as they’re drafting behind Trump’s base. A shift in US policy is going to have a dramatically larger effect than anything passed in the UK or Western Europe by dint of the size of its market for cars and lack of quality public transport in most major cities.

What’s going on?

Rosneft has reportedly closed a deal with commodities trader Trafigura to sell a 10% stake of Vostok Oil. Details about the deal valuation, how payment will be conducted, and more are lacking, but an unnamed source placed the sum around $7 billion. What it really sounds like is that Rosneft wants to make sure it can place the volumes with a partner willing to take on the related insurance and reinsurance costs imposed by use of the Northern Sea Route and also raise some quick dollar-denominated capital to keep improving its balance sheet. The company’s already paid off $5.7 billion in debt this year while slightly upping the share of long-term maturities in its portfolio. An infusion now would likely help financial reporting for 4Q and also strengthen the company’s revenue performance without actually producing any oil from the project yet.

October industrial production figures hint at how a potentially prolonged domestic demand crisis is sinking in:

Extractives’ recovery is going to wobble alongside oil prices and reflects partial easing against the initial OPEC+ cuts, not signs of health. Notably, production figures returned to small growth in the US for October (1.1% vs. Sept.). But that growth coincided with a surprise rise in US stockpiles of crude, offsetting bullish demand news out of Asia. Since Russian industrial production tends to track with oil and other commodity prices, underlying weakness of domestic demand is imposing a low ceiling on any recovery headed into 2021.

The government’s road map for 5G is, once again, under consideration. Current working plans call for 208.15 billion rubles ($2.75 billion), of which only 28.8 billion rubles ($381 million) is to come from the budget. Rostelekom and Rostec are expected to fork over the cash for investment, highlighting the budgetary and planning overlap between the security bloc of Russia’s SOEs and telecommunications. The new plan is a 22.4% increase over last year’s proposed spend on 5G infrastructure. It’s yet to be resolved whether companies will begin testing 5G frequencies in Russia using foreign equipment next year, but keep an eye on those negotiations. It’s likely the relevant business ministries are going to lobby to expand foreign investment into local production and haggle over defining what qualifies as foreign equipment.

Polling data on consumer savings and investment behavior collected by the RGS Bank and National Agency of Financial Information show a surprising trend: Russia’s savers aren’t changing their investment behavior much despite record low deposit rates in banks thanks to the key rate cuts by the CBR. Among those polled on a financial product by product basis, 81-86% of respondents aren’t changing things up. Savings accounts are increasingly popular, but there’s been little comparable flight into equities one sees in other economies based on responses. Yet the number of private investors trading on the Moscow Exchange has nearly doubled this year (+94.7%). As far as I can tell, this reveals how starkly divided the economic experiences of the current crisis have become by income segments of the population. Those with more money are pouring it into equities in hope of better returns (despite Russia’s equity underperformance relative to peers), while those more concerned about their earnings and jobs at the moment are probably not trying to generate returns so much as maintain liquidity to pay down debts or sudden bills. Savings invested in Russian equities still generate good returns, but as we’ve seen how differentially distributed inflation in Russia is at the regional level, savers doing the investing might be correlated to where they live.

COVID Status Report

New cases came in 20,985 yesterday, showing a noticeable decline off of Monday, but the entirety of the change was observed in Moscow rather than the regions:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

The head of Rospotrebnadzor, Anna Popova, has warned of a new strain of the virus found in Siberiak, though it shows no evidence of being more infectious or deadly. Ingushetia has received financial support from the national reserve fund to help pay for medical equipment and needs in response to COVID-19, an occurrence one would expect to become more frequent as winter rolls on and regional governments struggle. Local officials are getting creative. In Chelyabinsk and Magnitogorsk, city officials have teamed up with Yandex.Go to arrange for 28 “COVID taxis” to move patients and health professionals to hospitals as needed and reduce infection risks via ambulances. Limited help from the center is going to foster a lot of policy entrepreneurialism at more local levels of government. That’s great news for those otherwise depending on federal help, but a thin line to walk if local officials get too much credit and influence over local voters without the center playing a role.

Minus the Bear Market

MinFin’s calculated that the OPEC+ cuts have shaved off 2% of GDP’s (negative) growth this year. As a spot-check comparison, let’s use 2019 as a reference for how much economic activity that represents. Using nominal dollars — imperfect, but since oil exports are sold primarily in euros and dollars, it’s still useful — that’s a loss of about $34 billion of economic activity and/or value. As we know, MinFin’s response to the crisis was to raise non-oil & gas revenues to cover the shortfall. For Jan.-Oct., the budget missed out on an estimated 2.3 trillion rubles ($30.4 billion). Non-oil & gas revenues for October rose 50% compared to the last year, just over 1.4 trillion rubles ($18.5 billion). Leaving aside hard numbers and the size of the deficit, the biggest single growth driver for those revenues has been a 43% year-on-year increase in collections of VAT.

The link between oil prices, business cycles, and recessions in Russia is fairly evident and empirically robust:

Back in April, Russian economists were predicting a 2-year recession and the projected fall in disposable income was devastating. The picture has changed some since given China’s supply-side response lifted earnings in Russia’s exporting industries, but the story’s still a stark one that hits close to the situation as it’s developed. Incomes fell to 2008 levels initially:

The increased debt burden on the non-oil & gas sector has been paired with increases in taxes for oil & gas companies. That’s actually a big problem for the future of non-oil & gas revenues that could be realized. Vygon’s note yesterday stresses the point that increased taxation on the oil sector is going to undermine future investment and reduce net revenues. The oil sector tax code, as designed now, is meant to maximize the state’s capture of resource rents. Whenever oil prices rise above the $30-35 price band, it’s the federal budget that benefits most from rising revenues for oil firms, not the firms themselves. The effect is to disincentivize new investments without tax breaks or stat support, which means that the fiscal regime for the budget’s backbone since 2001 actually leads to chronic under-investment and under-production compared to Russia’s resource wealth. If the tax system focused primarily on raising revenues off of profits with a much lighter touch on severance/extraction taxes or export duties, this dynamic would not be so noticeable. But the knock-on effect is to actually suppress output for supporting non-oil & gas sectors that benefit from the money that circulates through the economy via services contractors, particularly in resource province regions. The fiscal regime suppresses both tax receipts and growth that could be realized via indirect channels.

Why flag this? Russia’s oil & gas companies are far less sensitive to increases in their relative tax burden than the non-oil & gas sector — other extractive industries are different, but face similar problems — since price increases are captured by the state and the tax code generally protects firms’ profits up to that price band of $30-35. An increase in their tax burden does much less to reduce future investment activity because they already realize less profit assuming prices rise again, which they very well may not, at least past the $60 a barrel range.

Non-oil & gas sectors, however, are much more susceptible to rising tax burdens because they’re working off a much lower base and the uncertainty of Russia’s business climate has a considerable effect on business planning and investment horizons. Rising tax collections last year were visibly doing nothing positive for the economy other than concentrating wealth in state hands that was then being ineffectively distributed to create more wealth and growth. Before the last oil crash, World Bank data shows that taxes collecting on income, profits, and capital gains represented less than 4% of all tax collections compared to when they exceeded 10% prior to the Global Financial Crisis and exceeded 20% prior to the 2001 tax reform that constructed the current regressive system. Tax revenues prior to COVID accounted for somewhere in the realm of 12-13% of GDP. The level befits an emerging market and isn’t the issue so much as how that GDP being taxed is composed and how those taxes are levied.

Marginal increases in business taxation have a much larger effect on SMEs than large, incumbent firms whose borrowing costs are much lower and themselves can collect monopoly or oligopoly rents because of their size. Putin in September noted that oil & gas revenues would only account for 1/3rd of all revenues in 2021, spinning the current crisis as a chance to renew and change Russia’s economic structure. The problem with that assertion is that the increased tax burden is sucking the air out of future growth by claiming a larger share of the national income earned by non-rentier businesses. Not only is that income not being spent adequately in response — the higher tax burden is just covering the losses of revenues from lower oil & gas prices — but it’s going to weaken the recovery of disposable incomes. Austerity measures don’t work to promote competitiveness or growth. That’s one thing. But they’re doubly ineffective when a country is trying to restore taxation for its non-resource sectors to levels they probably should have been taxed at for the last 2 decades.

Add in the continuation of price controls and pricing regimes subject to state monopoly interference, oligopolies, political nonsense, and constant tweaking because of Russia’s size, suddenly the problem grows. Resource-rich regions have more means of raising local revenue to pay for things than those without. Take warnings from the All-Russian People’s Front to Putin that as many as 85% of pharmacies are short on drugs used to treat COVID as an example. The strict regulation of prices to prevent inflation creates inflation via shortage by causing firms to under-invest into production relative to demand, and the rising burden of tax revenues collected by the state is not filtering back into the broader economy through adequate levels of infrastructure investment or social transfers. MinFin’s entire macroeconomic approach is deflationary, but that deflationary effect is going to fall on personal and business incomes — the new “cash cow” for the budget — faster and more effectively than on goods still in high demand facing supply constraints from under-investment and demand-suppression. In other words, wage deflation is inflationary. The Central Bank’s inflation targeting is useless in this regard. Russia is hindering its own recovery from COVID left and right. The “economic diversification” of the budget is actually the destruction of future growth.

Trafigura, Trafigura, Trafigura, Figaro

The announcement of Trafigura’s acquisition of 10% of Vostok Oil caught my eye since it’s not often we see companies sticking their neck out on a deal of that size in Russia, let alone a deal of that size to secure oil supply at the moment. Then again, there aren’t many greenfield projects of that size in the works and Rosneft already has dealt with Glencore when selling off shares to raise cash for the state budget. Trafigura recently acquired 3.01% of the Saras refinery in Italy — the biggest in the Med — just raised over $1.6 billion in debt, finalized a trust agreement for Telson Mining’s new gold project in Mexico, and plenty more. Expansion is the theme. I’m assuming that a mix of lower equity valuations for many projects, borrower desperation increasing Trafigura’s leverage as a potential lender or equity partner, and the dictum to not let a crisis go to waste rule the day at headquarters. The company is even teaming up with DP World to invest into Berbera Port in Somaliland despite it not yet gaining international recognition as an independent nation.

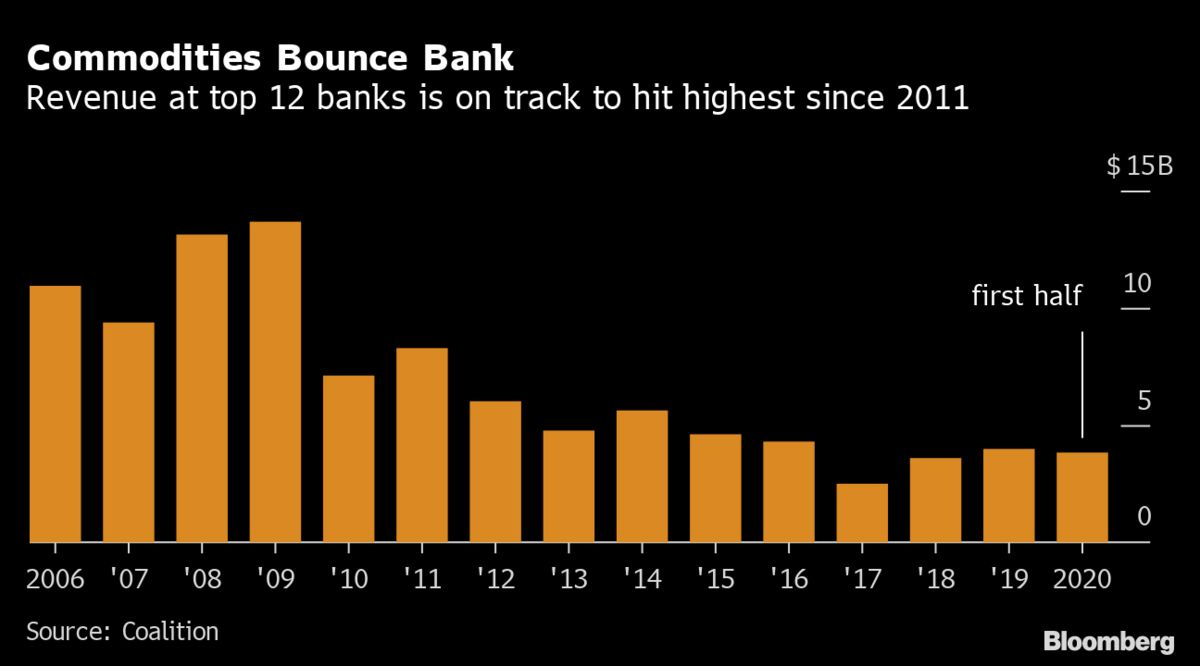

Commodities traders are fascinating beasts. They pick sides in civil wars, lift volumes of commodities from conflict zones, beg, borrow, and steal for access to supply, and actually benefit from price volatility during crises because of their role intermediating prices between end users, wholesale retailers, business consumers, and producers, let alone their own independently owned production capacity. Banks are in on the action too as commodity trading has become profitable for them this year:

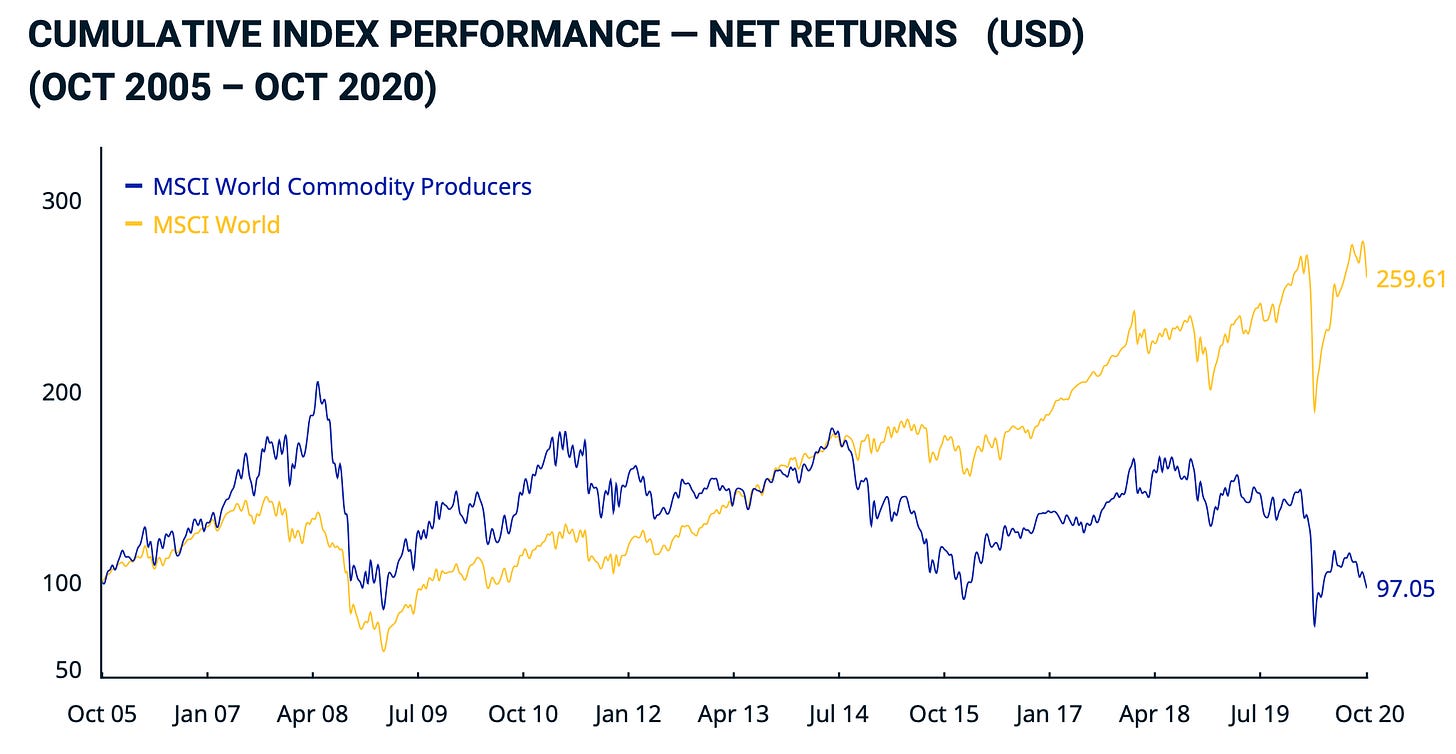

The energy transition is going to supercharge commodity earnings because of volatility and, more importantly, demand pressure for metals and minerals. Russian firms otherwise constrained in their ability to find foreign partners are going to double down on their ties with Glencore, Trafigura, Vitol, et al in the coming years to raise foreign currency capital and lock in a reliable customer. By the same token, trading desks for commodities at larger banks are probably going to have to bulk up to keep pace with a market set to takeoff. Weaker dollar or not, we’re headed into another commodity boom cycle. The question will be which commodities and who benefits given how badly commodities equities have performed since the last oil shock:

Oil prices are the story for that performance and the fact that G-20 economic coordination boosted prices back to +$100 a barrel highs after 2009. Shale obviously wrecked the medium-term price cycle, and by extension commodity producer performance linked to oil including major traders that are listed publicly. But the next generation of price rallies, while unlikely to produce the same marginal returns as oil, will provide huge upsides for producers getting into the resources that will drive the energy transition. Traders are sure to get a good cut of the action, especially as they diversify into renewable power generation and logistics to integrate more stages of supply chains and stabilize otherwise volatile returns. Russia Inc. will be watching that space as newer commodities become the main show in town.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).