Top of the Pops

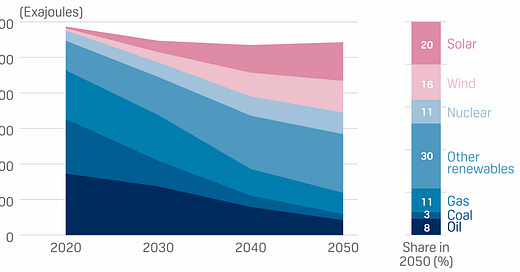

Saudi energy minister Prince Abdulaziz won some laughs when he claimed that the IEA’s net zero model, contested by the oil & gas industry and quite ambitious in its intentions, “is a sequel of [the] La La Land movie.” That’s probably a bit of stretch (and unfair to La La Land which surely deserves more derision), but the energy transition does pose huge problems pertaining to energy price inflation and energy mixes. Based on the IEA net zero scenario, the energy mix would look like something like this by 2050:

Coal prices have shot up because of the expected problems associated with the pivot for DMs to run their economies hotter, supply constraints from falling investment into production, and China’s demand. When you run economies hotter, you tend to outstrip energy supply faster and incentivize the use of the dirties fuels available cause the new capacity can be stood up more quickly. At least when it comes to the emerging markets that have relied on DM demand for exports. Eventually high prices make substitution more attractive, though that’s limited by the spike in commodity inputs for all manner of energy sources. OPEC+ is right to balk at the idea that we just cease investment into new oil & gas production. Energy prices are likelier to rise than not in the near to medium-term. They’re wrong, however, to rest on their laurels. Though its support schemes are in flux (and may be amended with future legislation), IHS Markit has measured the US market as the most attractive for non-hydro renewables investment globally and it’s the US driving global growth right now and pushing marginal commodities demand into developed markets. US power over oil & gas markets is alive and well. It’s just evolving, particularly since IEA expectations that oil demand recover to 2019 levels in 2022 come with the major shift since China’s probably not going to drive commodity markets the same way again, especially if it accelerates its EV deployments.

What’s going on?

According to Central Bank surveys, business inflation expectations are now at post-2008 record highs despite all of the government’s efforts to tamp down price increases and repeated assurances from MinFin that inflation was peaking in March-April. The business survey data running back to 2013 shows just how bizarre the conviction that current inflation levels are indicative of excessive budget spending, debt expansion, and otherwise manipulable causes truly is. Ignore the specifics of the methodology, they’re a bit vague but the important indicator is simply that the % indicates the “balance” of business responses i.e. how many net expect price increases:

Inflation expectations ran lower from April to August for business than the beginning of the year despite that time accounting for the largest budgetary increases since demand was way down, then followed by a spike from reopening, followed by a drop-off from renewed falls in demand despite consistently rising commodity prices. This year those expectations have taken off alongside commodity price increases and global supply bottlenecks. This is a terrible indicator because of how relatively weak domestic demand is. Russia’s importing inflation and worsening it via import substitution and some of its approaches to pricing agreements. Consumer price inflation has accelerated again back to 5.8% in annualized terms officially, the worst reading since 2016 and bizarrely low given just how much higher business expectations are for price increases now than in 2016. Either businesses really are absorbing most of those increases, they haven’t yet raised prices too much — likely given businesses want to hold off as long as possible to avoid losing customers — or else the topline figure just isn’t telling us what most people are experiencing. My money’s on the last option, with the other two true to varying degrees depending on the sector and levels of domestic demand uncertainty.

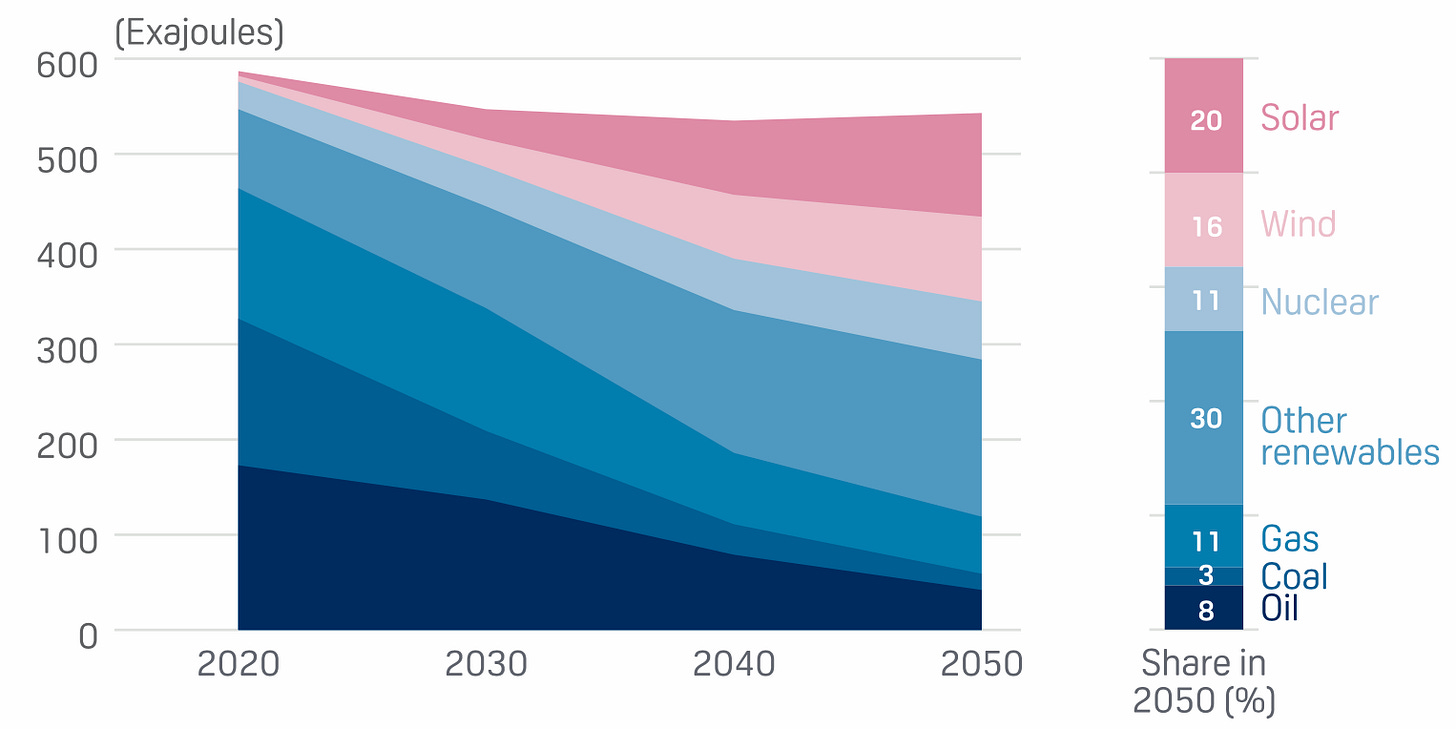

The depth of the migrant labor shock to Russian firms and markets can’t be overstated and we’re only now seeing the beginning of a recovery, one that will likely take a long time to realize without additional state support for wages and a more sound inflation strategy. Fewer migrants means tighter labor markets means higher nominal wages from firms competing for labor, but now doing so at a time when prices for everything keep rising and it’s unlikely there’ll be much more of a policy-led demand impulse through the rest of the year:

Title: number of foreigners in Russia at the end of the month, mlns

According to RANKhiGS and Gaidar Institute monitoring, the number of foreigners living and working in the country has nearly halved since the start of the crisis. No wonder there’s been no hesitation putting prisoners to work. Prisoners are up in arms because of the bureaucratic cruelty of the system — mandatory labor is seen as a ‘lighter’ punishment than time in a labor colony, and prisoners lose their right to early parole once the punishment is changed to a lighter form. In other words, they’d be out of jail faster staying put than being forced to work. Once more prison labor is deployed on construction projects, the relative demand for migrant labor is likelier to diminish, which means that future arrivals might end up depressing wages to a greater degree right when it’s most important that real wages and real incomes rise. 2021 and 2022 are going to be crazy years for labor in Russia.

Minister for Trade and Industry Denis Manturov successfully brokered an agreement between Russia’s metallurgical sector, MinPromTorg, MinFin, and MinEkon to offer discounts for state procurements in light of rising prices. The ministries and presidential administration played good cop, bad cop. The threat of an additional 100 billion rubles ($1.36 billion) in taxes on Russia’s major metallurgical firms proposed by Andrei Belousov drove them to the table with Manturov to reach an agreement. Hardball politics to achieve economic policy goals are pretty standard fare, but this episode is novel because of what it suggests Mishustin and the economic policy managers in the presidential administration think — inflation begets profits for exporters and those benefiting from global price cycles, so we’ll threaten you with taxes on those profits unless you do us a solid and swallow some of that inflation for our own sake. It’s illogical. All they’re doing is reducing businesses’ capacity to invest into production and creating a new political pressure. Firms will prefer to sell to the private sector if they can where they can realize higher margins, a problem that’ll only be avoided because of the implicit threat of coercion if they go too far. If the state-business relationship from 2000-2013 was broadly that business ought to stay out of politics in exchange for some level of ‘protection’ — admittedly this was never entirely the case — then the post-2013 contract has frayed to the point where businesses are now seen to basically serve the state at its own convenience. The threat of taxes made sense conceptually since the sector average tax burden is just 5.4% and MET + customs duties don’t exceed 8%. There’s plenty of space to raise taxes. It’s just that the discounts won’t do much to help inflation, set bad precedents, and presage a likely systemic increase in tax rates to capitalize on the new commodity price cycle.

For those wondering what Surgutneftegaz is really for, we’re finally getting an answer. The company has sat on over $50 billion for a long time with a market capitalization worth less than half the amount of cash it holds in hand. Now Putin has asked general director Vladimir Bogdanov to help directly support multi-child families in line with assurances that more state resources will be spent doing so as well. It’s time to turn the cash pile whose owners aren’t transparent that defies business logic to most into a political tool to reduce the demands on state reserves to help the public. We don’t have too much else in the way of details here but Putin went out of his way to refer to Bogdanov as “ungreedy” — Mishustin’s attack on greed has now been amplified by making it clear to other business leaders what’s expected of them. Big businesses can no longer view their earnings and reserves as ‘their own’ the longer the economic crisis drags on. We can see shades of this playing out in the reworked infrastructure spending plans since any state contract is effectively a rent awarded to the right individual(s) or business. Not only have they delayed their main targets to 2030, but they’ve only upped the road-construction budget significantly and not rail. The increases laid out for roads through 2024 — about 80 billion additional rubles — will all be wiped out by price increases in a matter of months and the lack of new rail investment suggests that the transshipment gamble for rents from China-Europe trade haven’t panned out. Increases have been targeted in digitalization and healthcare, services that the regime needs to work to reduce the public’s exposure to inefficient bureaucrats and manage falling living standards. Businesses are likelier to have to cough up more for future infrastructure expansions, but that raises the specter of renewed fights between state monopolies and monopoly operators and the private sector. Add the fact that Boris Titov, the old guard business ombudsman, wants to leave the job next year with Oleg Deripaska as a potential replacement and the terms of the ‘social contract’ with Russia Inc. are looking worse.

COVID Status Report

8,832 new cases and 394 deaths reported yesterday. The variation continues to come from Moscow with the caseload in the regions from the Operational Staff showing a very, very slight consistent upward trend from the last few weeks. When we look at the total % of population vaccinated, Russia’s struggles look all the worse:

Russia’s lagging India in terms of % population vaccinated and Turkey has roughly doubled Russia’s vaccination rate as of June 1. Rosstat’s data citing COVID as cause of death, not excess mortality which is far worse, still shows around double the number of deaths cited by the Operational Staff. After Putin came out against mandatory vaccinations, Federation Council speaker Valentina Matvienko has also said they’re not an option. Mongolia has just opened up travel to Russians who’ve received both doses of Sputnik-V. The EU will decide whether it registers Sputnik-V on June 6, at which point a positive decision would allow Russians with both doses to travel freely. Lack of stronger vaccine action is politically safe, though. Levada shows that now 55% of Russians aren’t worried about getting COVID vs. 42% who are. Only 7% of respondents said they’d gotten officially diagnosed after getting sick with COVID and another 17% said they got over it but weren’t diagnosed. 65% say they haven’t had it. At some point, I’ll have to untangle this data more but safe to say that per Levada, only 35% of the population can safely be said to have immunity from vaccines or antibodies, with the latter group less safe over time given risks from mutations etc.

Summats and Troughs

The planned Biden-Putin summit in Geneva, Switzerland set for June 16 — two weeks from today — is drawing all manner of speculation, wonkish ‘think’ pieces offering policy suggestions that offend no one, and another test for the Biden administration’s efforts navigating out of the performatively unilateralist approach to foreign policy Trump adopted. The decision to maintain the US withdrawal from the Open Skies Treaty highlights that the White House knows its domestic audience. It can’t afford to look soft in the middle of a bevy of negotiations on social and physical infrastructure spending, attempts to pressure democratic senators Joe Manchin and Krystyn Sinema to do their jobs and pass key legislation, as well as attempts to make sure voting rights make it onto the senate floor this summer or early fall. Naturally, most attention has been drawn to arms control talks as a hoped-for breakthrough. These summits are always an excuse to offer one’s opinion about “what is to be done?”, and on that front, the classic artificial division between economic and security-centric understandings of strategy and approaches has remained unchallenged.

Samuel Charap’s early May commentary for War on the Rocks is a great summation of the shortcomings of US policy, but ultimately falls short of acknowledging that there is a broader political economy of the relationship bilaterally and globally that challenges the formulation provided somewhat. It also privileges bilateral dealmaking when sometimes the most effective sources of pressure lie in dealing more proactively with Kyiv and other governments to address domestic challenges, not security ones. Perhaps the oddest assertion is that the US has ‘ceded the initiative’ structuring Moscow’s choices because of the overly narrow, in my view, articulation of how US policy choices and its economic role structure Russia’s options. It all begins with the traditional understanding of economic power as some sort of latent base of economic power that then provides a state with material means to sustain its military influence and so on:

“Efforts in Washington to intellectually retire Russia from great power status, premised on the idea that it is a power in decline, are not well-grounded in empirical reality. Russia remains a leading military power, which effectively spends in the range of $150-180 billion annually on defense (in purchasing power parity terms), to say nothing of the fact that it is America’s only real peer in nuclear weapons. Economic stagnation is unlikely to meaningfully reduce those aspects of the state’s capability that make it a challenge to U.S. interests.”

As usual, we finish the piece without having any idea what US interests actually are. To assert that Russia is a ‘significant and enduring’ challenge to US interests is well and good, but these claims tend to be rooted in a reflexive assumption of primacy that too often rewards administrations for ‘doing something’ instead of thinking in terms of structural trends that go beyond specific Russia policies. Syria and Libya are perhaps the best examples — the argument is that the US has a compelling national interest alternately because of the cause of ‘freedom’ or else because of the importance of stability in the Middle East, the latter of which surely hasn’t been improved by US policy since 2000. The stability argument also usually rests on old canards about risks t oil markets rooted in the oil crises of 1973 and 1979 that, despite Saudi Arabia’s relevance as the swing producer and ‘glue’ holding OPEC together, ceased to be of any reality once the Federal Reserve radically reduced the cost of credit in response to the Global Financial Crisis and had already long diminished in importance. In Afghanistan, the US has always determined its own fate. Crimea and Donbas were quite different as a matter of course, but the US was still able to coax European partners to at least fall in line on sanctions. Rather strangely, the piece argues for a broader conception of statecraft but says nothing about economic diplomacy, America’s potentially transformative role on global energy markets, or the underlying economic crisis across Eurasia that allows Russia to sustain a degree of influence above its so-called ‘economic weight.’

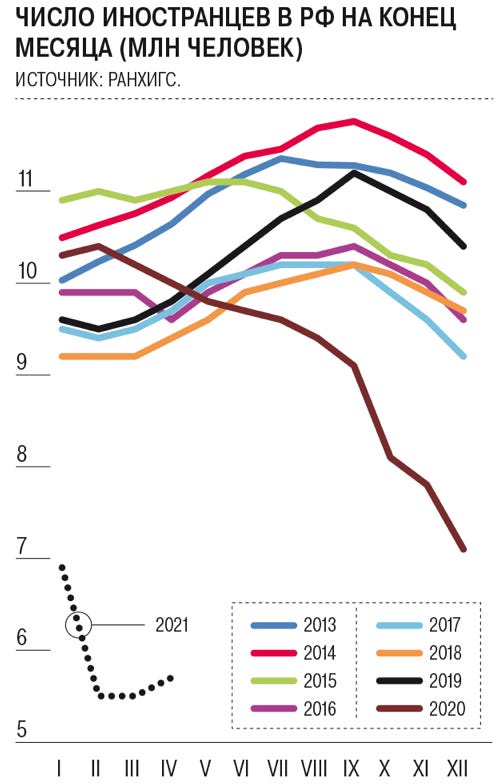

Russia’s economic weaknesses and persistent economic decline despite initial gains in the early 2000s have always structured its options, as have financial sanctions now straining the capacity of Russian firms traditionally used to ‘buy’ influence to achieve political ends effectively. Domestic economic and political institutions shape the manner in which states conduct their respective foreign policies, and it’s safe to say that Russia’s domestic struggles with extraction of all shades do, in fact, pose a long-term risk to its capacity to sustain its influence. It may have broad, though often shallow, capabilities to project military power, use deniable assets for intelligence purposes, or else impressive intelligence capacities, but these are relatively hollow sources of power for the same reasons Charap cites as limits on US policy dealing with Russia. Russia’s room to maneuver is so constrained that the best it can muster in Libya or the CAR are mercenaries, that its role in the Syrian conflict was ultimately in support of Iranian troops or proxies doing most of the work holding territory, and it’s most comfortable maintaining lower-grade involvements in conflicts to allow officers to gain field experience and train up units while avoiding excessive ‘burn’ through stockpiles of supplies/armaments and exposing the regime to too much domestic scrutiny. You’d think that Russia’s reserves powered by its oil & gas-led current account surplus would buy it a modicum of economic influence even with sanctions in place:

Alas, they don’t because they don’t end up buying productive assets or lending domestically or abroad. Worse, the politics of the petrodollar are in for a nasty shock as other commodity classes superheat in the years ahead to keep pace with decarbonization while Saudi Arabia is far better positioned to maintain its output levels with limited emissions compared to Russia.

The deafening silence in Washington about the extent of the economic crisis now underway in Russia rests on the mistaken belief that stability is an enduring reality of Russian politics and policy. Any US-Russia summit is a crucial opportunity to try and forge some semblance of stability and sanity, especially when it comes to arms agreements to reduce the size of nuclear weapons arsenals. However, Charap’s call to expand the scope for statecraft should really be aimed at incorporating economic policies and imperatives like the fight against climate change into strategic assessments of power relations with Russia. The quiet revolution in the Biden administration’s accounting of the effect of the national debt has far greater structural implications for both domestic politics and foreign policy than a one-off summit:

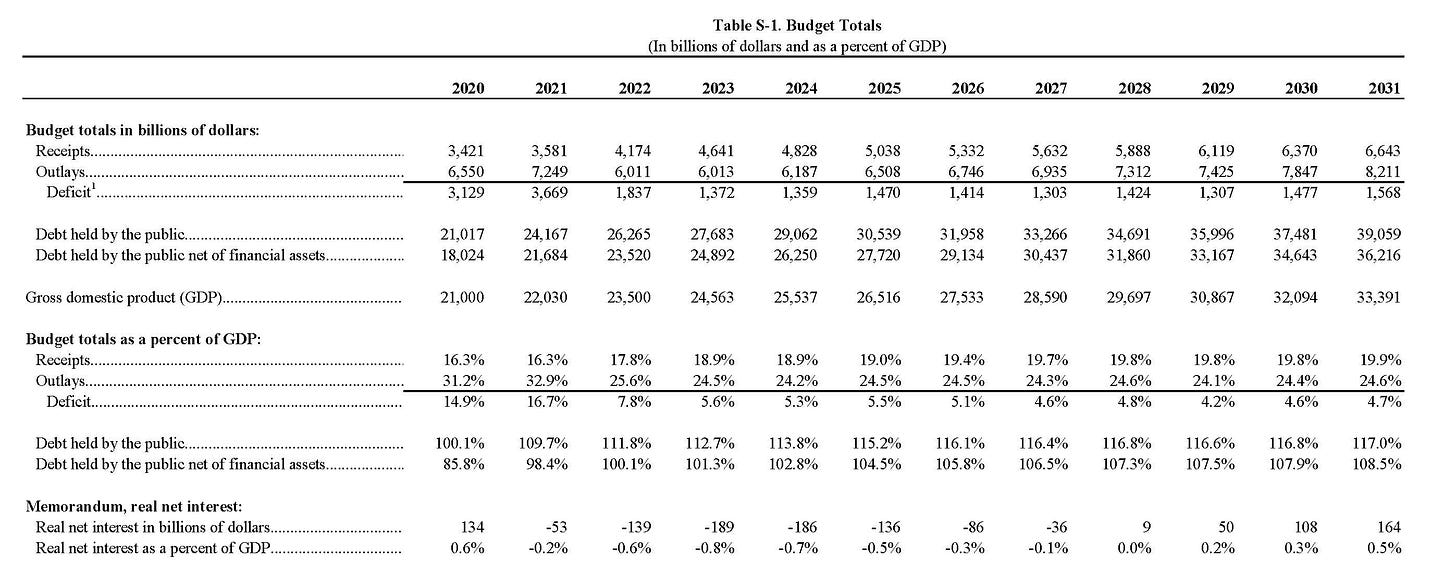

Real net interest payments on the national debt are negative through 2028 despite its massive size in absolute terms. In effect, there is no convincing argument that large tax increases are needed to finance a massive infrastructure and decarbonization spending package that would produce growth, jobs, and create new competitive advantages for manufacturers, exporters, and US corporations. By the same token, this means the US faces few constraints running its economy hot, which would then ‘export’ inflation onto emerging markets and into Russia, particularly since a green agenda is very commodity-intensive. We’re seeing an economic paradigm shift that poses a huge challenge for emerging markets if developed ones unshackle themselves from the deflationary assumptions that ruled policymaking consensuses for decades. That’s how you break the power of petroleum exporters and create a situation in which Russia becomes ever more reliant on a strong role in the Middle East to preserve market influence, the stability of the ruble, its budget, banking sector, and current account unless it somehow manages to replace petrodollar earnings with metal export earnings (which wouldn’t cover the budget, but may alleviate other issues pertaining to the balance of payments and availability of foreign currency). This shift also means there aren’t really any reasons why the US can’t do far more to help countries finance these same efforts, from Ukraine to Turkey to Georgia to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. The United States needs to relearn development economics alongside the changing debate on domestic economic policy. And if Russia hands are serious about ‘expanding’ the statecraft toolkit, they need to link economics, market trends, and the political economy of stagnation in Russia with the energy transition and the slow, painful, as yet unclear and unfinished death of American neoliberalism.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).