Top of the Pops

Sadyr Japarov came in first (as expected) in yesterday’s presidential elections in Kyrgyzstan, completing his meteoric rise from prisoner to president from the country’s protests and political instability in October when the public and various opposition parties protested the integrity of election results. Japarov has already used his victory to call on the opposition to unite and work together for the people and play the role of unifier and national healer. The big ‘scare’ to come now lies in an expected push to move the country towards being a presidential republic with greater lawmaking powers delegated to the executive branch than at present. Not only was the reform worked up without significant public or parliamentary input, but it transparently was designed to undercut the tenuous balance of inter-elite in the country by reducing the power of the country’s varied and geographically divided regions from using a parliamentary power base used alternately between groups from the country’s north and south to seize power, pass friendly legislation, and provide favors to friends. Japarov’s push fits into broad comparisons with Trump and other right-wing populists who seek to centralize power in the hands of the executive as a means of ‘draining the swamp’ and more. There’s talk of ending Russian’s official status in Kyrgyzstan among other symbolically nationalist policies. A quick reminder about Kyrgyzstan’s remittance dependency, with the following Central Bank data (in US$ mlns) citing where money transferred into the country is coming from:

Virtually all of it comes from Russia and it props up currency stability, purchasing power, standards of living, and bank solvency. If Japarov truly intends to be assertive in the face of both China and Russia, he’ll need foreign partners of some kind since currency earnings from Kumtor mine — and the global silver market — aren’t going to generate growth magically, especially if he goes ahead and tries to nationalize Kumtor. Chinese investors would immediately wonder about investment risks, and the already relatively scarce foreign capital available for much-needed investments would surely react negatively to a nationalist turn. Much has to happen and remains speculative, but this could get wild, especially if Moscow gets annoyed.

What’s going on?

Mishustin appears to be taking the reins over Russia’s regulatory chaos, with an end of year government decree that reins in the power of ministries with delegated regulatory lawmaking authority in the executive branch. In effect, ministries have to show that a proposed regulation that has been put in place is better than alternative approaches and is actually achieving its intended effect. This shift to “proven regulation” standards is meant to protect businesses from the troublesome whims of Moscow bureaucracies that frequently fight each other for influence and power while also advancing the interests of their own allies. Further, MinEkonomiki is regaining some of its lost luster after Siluanov gutted its role with Oreshkin at the helm and is responsible for administering a unified register tracking all of the normative legal acts passed into law via delegated executive authorities that affect businesses. The Ministry of Justice then oversees their legality while MinEkonomiki oversees the actual procedures in place. It’s a smart reform on paper, one that strengthens the ‘economic block’ and Mishustin’s influence over policy, but it’s simply going to shift the onus of existing fights over policy onto new procedures and figures without substantively fixing chaos. Still, it could provide some relief to Russian firms battered by years of increasingly securitized and incoherent economic policymaking.

Kommersant’s got an eye on the latest unemployment figures from the US, noting that the current wave of the infection has led the economy to undershoot expectations headed into January. What’s hilarious, though, is that the coverage pointedly notes new restrictions on economic activity are the primary culprit to puff up the ‘quality’ of Russia’s response rather than acknowledging that the virus itself has also played a large role in changing behaviors and reducing activity in the service sector (though we’ve clearly learned that when lockdowns are eased after a time, people get careless). The following is in millions:

Orange = long-term unemployed Blue = temporarily unemployed

What’s also rather confusing about the framing, subtle it may be, is that 42% of respondents polled by the Fund (for) Public Opinion believe unemployment in Russia will rise this year and the 50% increase in unemployment benefits from April i.e. a monthly increase from about 8,000 rubles to 12,130 rubles has been locked in through 2021 because of expected persistent job losses. It’s not a big story, but interesting to see this gamesmanship in the press take place, particularly with the new COVID variant creating much greater transmission risks and widespread expectations with the public that they have to save more now.

New polling shows a problem that reflects the country’s economic failings: 22% of those polled 18-44 years of age don’t want to have kids. That figure was just 5% in 2015. Polling data is always wonky on topics like this, but the trend is clearly observable and believable. Per Alla Marakentseva in the interview with VTimes about it, respondents notably tried to ‘negotiate’ the situation by providing the conditions that had to be met in order for them to reconsider having kids. 15% of the current cohort of 30-40 year olds won’t have kids per the current figures. At the same time overall birth rates appear set to decline, the number of families with 2 or more children appears to be rising. I wonder where those families, but am pretty sure it speaks to the problem of escalating costs of living in Moscow and other metro centers where the jobs are against stagnant or declining wages, thus intensifying the ‘bifurcation’ of birth rates depending on social class and where one lives geographically. Russia’s demographic woes are generally overstated, but this is a trend that clearly has economic roots and should worry policymakers.

It appears that the restructuring of development institutions will drag out through the entire year as the government has agreed to three potential roadmaps that call for VEB.RF to oversee them, for mergers of different institutions, or else for the liquidation of them. First, they have to work out the actual ‘normative act’ to enable changes to take place and assess the effectiveness of existing institutions, which is surely going to be a bit of a spaghetti throwing contest behind closed doors. After that’s done by April 20, proposals to fold some of them under VEB.RF’s wing will be fielded through the end of July as they work out how to hand over assets and what to hand over. In the end, Igor Shuvalov is going to be overseeing what’s left from his perch at VEB.RF, and this suggests that behind the facade of reducing waste and stamping out petty fiefdoms, Mishustin is really handing the portfolio to one from Putin’s traditional circle in the Kremlin and instituting ‘personal responsibility.’ By making one person and organization responsible for handling them, it’s that much easier to point the finger and demand action.

COVID Status Report

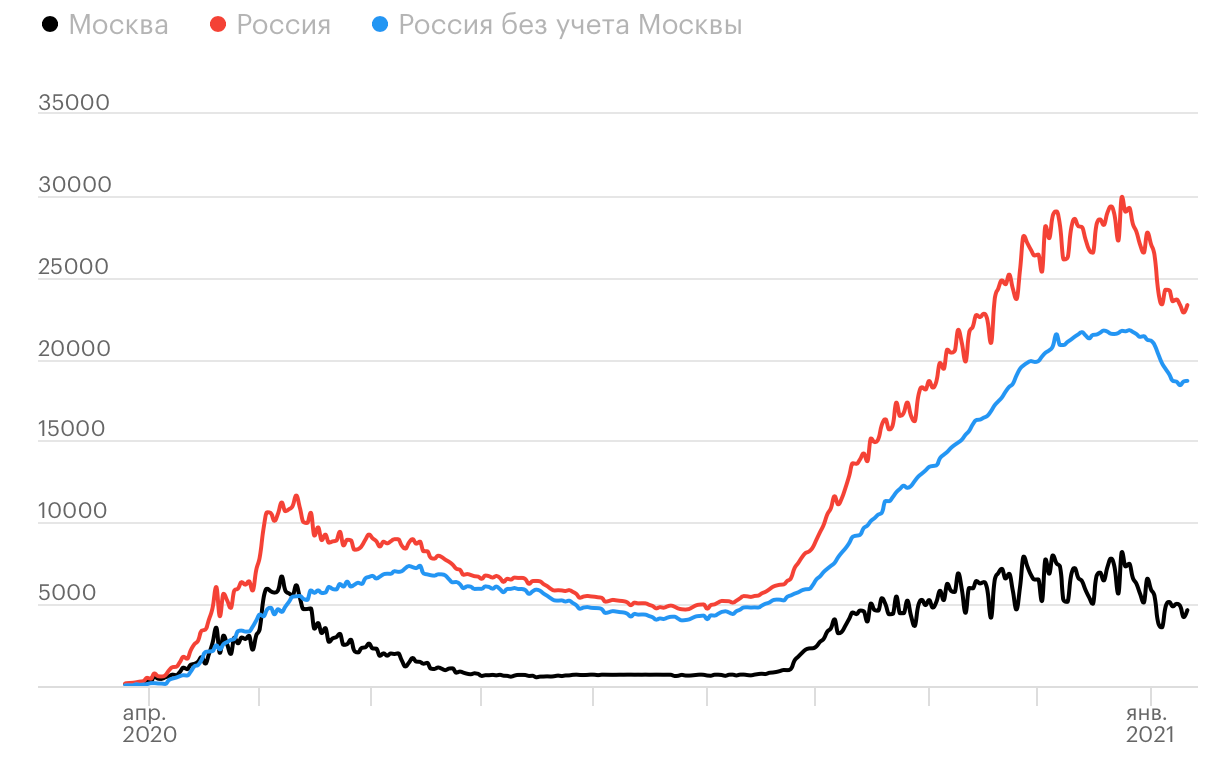

There were 23,315 new cases and 436 deaths recorded in the last 24 hours. What’s worrying, however, is that while cases have dropped from their highs, they’re showing signs of plateauing in their decline:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

Some of that could be Christmas, but what’s more worrying is that the first recorded case of the variant found in the UK happened yesterday as a result of Russians returning from the US. Only one person was found to have it, so it may well not have spread, but given its higher transmission rate, this should be a serious cause for panic in Moscow. The country’s lax attitude towards restrictions, dressed up as an economic necessity despite the service sector’s small share of national GDP, was feasible based on the old expected infection rate. Aleksandr Ginsburg, director of the Gamelen Center which worked on the Sputnik-V vaccine, notes that there’s a very high probability Russia has its own variant more similar to the new strain found in the UK, new strain in Brazil, and elsewhere. That new strain could be part of the sudden stop to the case decline outside of Moscow, and is something to carefully watch. Russian policymakers may have to dig deeper with a little more deficit spending if things get worse again.

The Lost Boys

The World Bank’s calls to take action so as to avoid a “lost decade” post-pandemic deserve serious consideration as the global economy tries to shrug off the effect of COVID-19 in the coming year to 18 months. One thing sticks out from the early part of the report that should rattle Moscow. The current ‘fourth’ wave of debt accumulation since the Global Financial Crisis, eased mightily by a shift to a persistent low to zero or even negative interest rate regime in the world’s leading currency issuing economies, creates structural risks of a future financial crisis just like past borrowing waves have. But what’s striking is how the post-GFC regime has affected emerging markets much more than advanced economies, including China:

It’s not groundbreaking stuff, but the extent to which debt has financed the last decade of China’s growth has been debt-financed and that even though it has structurally shifted from relying on exports for as much as 40% of GDP to a mark closer to 20% coming into the COVID shock, the steady increase of debt held privately in the Chinese economy creates a growing drag on growth. Even the IMF is still warning that China’s recovery, while impressive thus far, remains lopsided with consumption lagging where it should be. Russia’s ‘securi-nomic establishment’ — the figures who hail from the security world and blend its economic orthodoxies about not holding debt or spending lavishly with security aims in foreign policy — like to rail against the risks posed by excessive debt levels, financialization, and the other sins of capitalism that they identify with the traditionally American-led international system. Yet they are completely silent about how China, the engine that could for Russia’s commodity exports and its economic fortunes in 2020, is not only more indebted overall than the US at this point, but about to struggle with its own financialization at a new level as capital controls on inflows are slowly liberalized and more international banks open up shop.

Check the stats from Jan.-Sept. for Russia’s trade balance. I pulled a report on October data for Russia-China and used it as a proxy to calculate what it would have been for September:

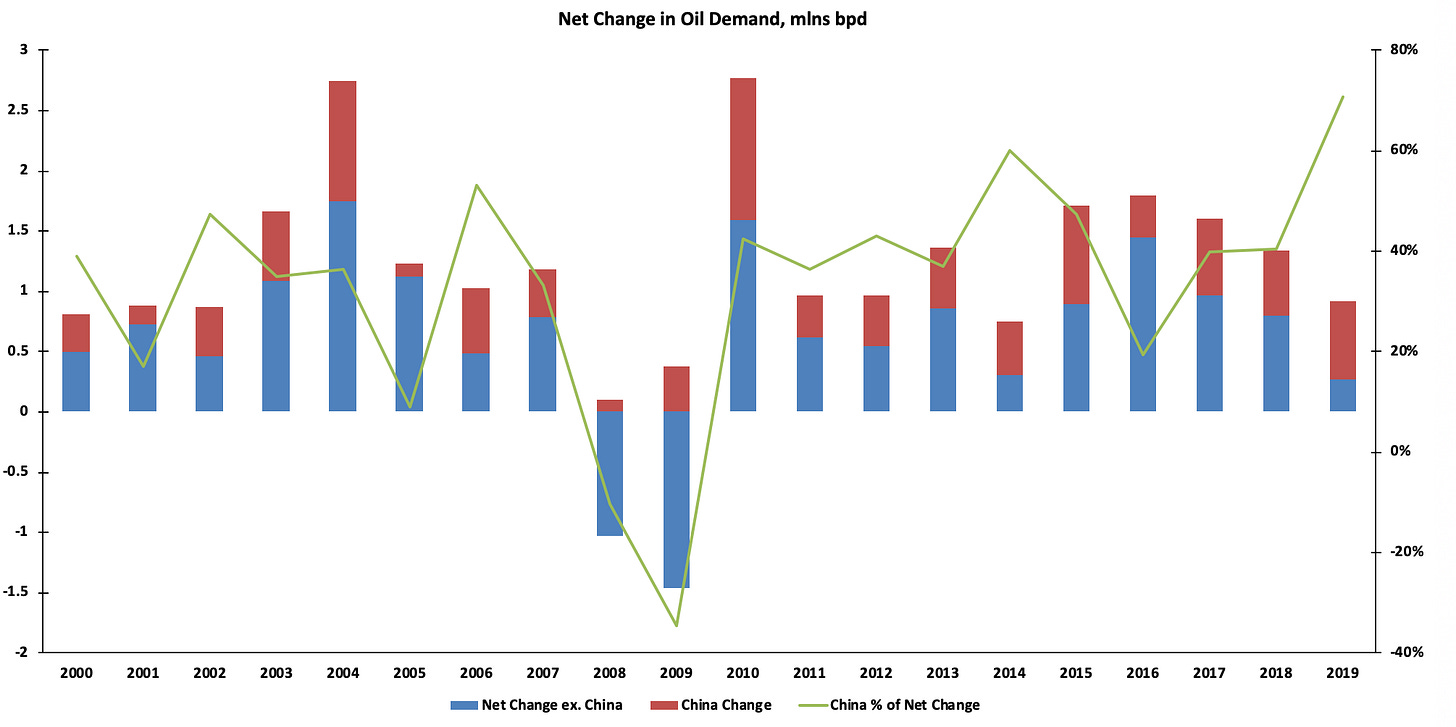

Largely thanks to low oil prices in 1-2Q, Russia actually ran a net trade deficit with China over the first three quarters of 2020 and its deficit with China was equivalent to approximately 14% of its net surplus with all non-CIS economies. There’s little reason to expect a similar price crash, but that current account pressure is real and, in the immediate term, is only going to be relieved by strong oil & gas consumption and price pressures in China. The coldest winter in decades has sent up coal and natural gas prices, but it does precious little to redress the structural problem: the surplus countries crucial for Russia’s current account are actually everyone who isn’t China, and a majority of those consumers are set to decrease their net oil & gas demand with active policy intervention in the years ahead. Further, China’s share of global oil demand growth was rising in relative terms prior to COVID, which may not last but is certainly tied to its inexhaustible appetite for debt (from BP 2020 data):

Late 2020 defaults among Chinese state-owned enterprises has signaled that financial and political authorities in Beijing now wish to limit the moral hazard that long benefited SOEs. The debt binge in China — led by corporations tasked with meeting investment targets to generate enough economic activity to meet annual GDP growth targets irrespective of whether said activity is sustainable or needed — is a big part of the reason the IMF cut China’s 2021 post-COVID bounce recovery to an expected 7.9% growth. Financial risks are massive, and the inefficient allocation of capital as a result of over-indebtedness among Chinese corporates poses a huge potential drag on future oil & gas demand growth since those grandiose investment targets lead to job creation intended to avoid things like the provision of an adequate social safety net, which would be insanely expensive for a country as large and aging as quickly as China. The imposition of real consequences in place of guaranteed bailouts can unwind some risks, but it means steadily defining down growth for the Chinese economy.

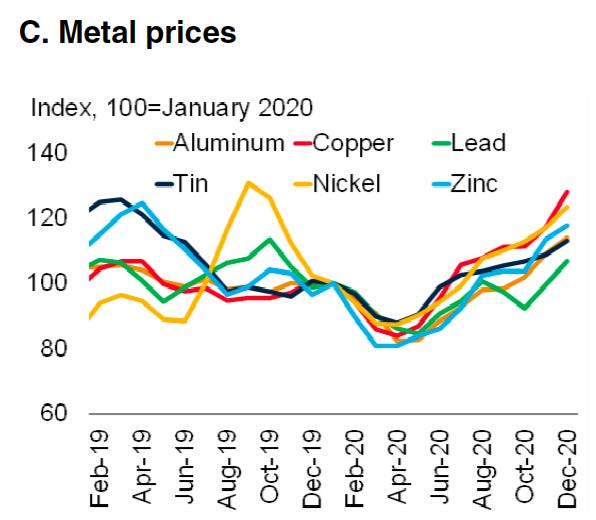

The debt binge in China has been central to Russia’s hydrocarbon export growth the last decade. The National Security Council can pat itself on the back for being so stingy at home for the sake of macroeconomic stability, but this demand growth story is ending and it’s precisely the systemic risks they prefer to lecture the United States about that pose a problem in China, where it’s more like the Wild West when it comes to securing liabilities. Sinopec, China’s largest refiner, is now predicting oil product demand in China to peak by 2025 without assuming a financial crisis hits demand. The new commodities ‘super cycle’ is not likely to benefit oil much at all, but the rise in commodity input prices for exports is something to watch, both for price inflation and for China’s export competitiveness as the CNY strengthen — this would lower input costs for production but render exports of intermediate production less competitive from China, creating a potential drag on consumption as it feeds back into layoffs and/or higher corporate debt levels to sustain employment for political ends:

As metals prices rise, consumer price inflation should follow, at least a bit, which would then undercut the consumer-led recovery the IMF is hopeful will takeoff in China in the coming year. Russian exporters might benefit, but the metals & minerals firms in Russia can’t hold a candle to oil & gas when it comes to maintaining the country’s current account surplus. At some point, Russia’s economic policymakers have to grapple with the truth that it’s not the Anglosphere likely to create the next financial crisis. It’s more likely to come from China and the EU given how correlated Germany’s economic tidings are with China’s performance. The bet that China was a great geopolitical ‘diversification’ play was always a myth: commodity prices are set globally, and the global forces, trends, and problems at play now lacking any sensible coordination between leading economic powers can destroy the best laid plans. If Russia ends up running a persistent trade deficit with China, its only hope to remedy the situation and leverage its comparatively cheaper labor is to reach trade agreements that would expand market access for Chinese exporters. Doing so would threaten employment and corporate earnings across Russia’s regions, core to the sustainability of the regime’s political base of support and unpalatable given the frequent public backlash to Chinese investment at the local level. The maturation (and distortions) of China’s economy — limited given the CNY remains an immature international currency, of course — will be a huge pressure point on Russia in the years to come. Moscow’s already dealt with a mostly lost decade since 2013. Another will be much costlier politically as energy markets and global growth evolve.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).