Top of the Pops

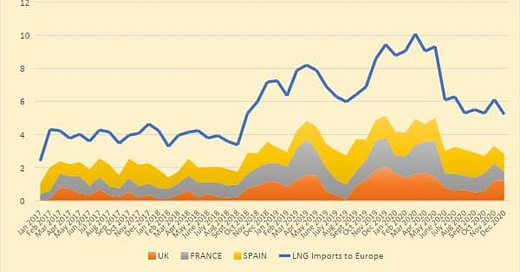

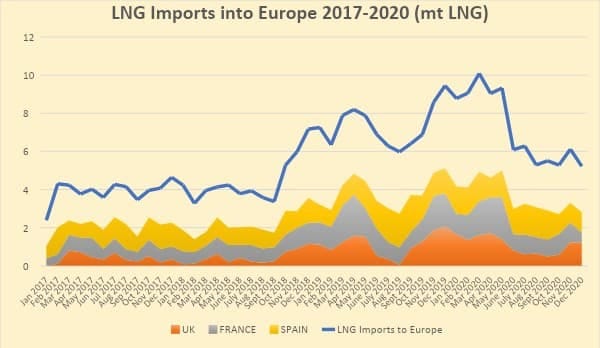

Russia and Kazakhstan used yesterday’s OPEC+ meeting to lobby for production increases in February, a transparent tactic to use the end of the winter turnaround season for maintenance at various fields that contribute to current cut compliance to bump investment and avoid well shut-ins. Azerbaijan has little skin the game. Production’s past its peak and the launch of natural gas exports from Shah Deniz via the Southern Gas Corridor to Italy 4 days ago means that Baku’s focus is elsewhere. It can free ride on the market price recovery and, even with SOCAR’s greater stake in oil projects after they renegotiated production sharing agreements, international oil majors don’t want to increase output with demand uncertainty so high. The launch of Shah Deniz comes as European LNG demand hasn’t been as strong as predicted competing against piped gas volumes, with future pressure bound to come from EU regulatory debates over policies meant to accelerate the switch from natural gas:

The Saudis are still trying their best to run the show in OPEC+. Saudi oil minister Prince Abdul Aziz cautioned other OPEC+ members “Do not put at risk all that we have achieved for the sake of an instant, but illusory, benefit.” Translation: guys, you won’t win price wars and it’ll hurt you as much as us, if not more. Punting on a quota decision dovetailed with the latest whiplash national lockdown in the UK (Lord, do I tire of Boris Johnson’s bumbling incompetence and cowardice) to pressure oil prices downward as reality, once again, sets in that distributing vaccines and developments like newer COVID strains with higher transmissibility are still massive hurdles for demand recovery. The only upside is that hundreds of millions of consumers deleveraged last year given lockdowns and spending priorities, which means weaker debt headwinds for recovery such as those that took place after the Global Financial Crisis (itself a crisis intimately tied to consumer leveraging given the explosion in mortgage borrowing and securitization).

What’s going on?

For those interested, here’s a full interview RBK conducted with deputy minister Alexander Novak. I only had time to skim through, but figured I’d flag it and pull out the headlines RBK ran with from it. It seems that Novak helped shepherd through a deal with Lukashenko’s government to ship Belarus’ petrochemical exports — one of the most important drivers of its current account earnings — through Russian ports to deny the Baltic States, particularly Lithuania, revenues from transshipment. The move visibly deepens Minsk’s dependence on Moscow, but of course Lukashenko made sure to close an end of 2020 deal with Azerbaijan’s SOCAR for crude oil shipments as a handy reminder to Moscow that he still has options. Novak also confirmed expectations that Nord Stream II will be completed in the months to come with support from European partners despite US sanctions.

It’s not a Russia story, but VTimes pulled an NYSE announcement that several planned delistings of Chinese firms had been called off:

Under Executive Order (EO) 13959, as of 9:30 a.m. on Jan. 11, all companies identified as a Communist Chinese Military Company are to be delisted from US exchanges. The backtrack could well just be internal deliberations thinking Trump was overreaching, but it’s worth asking to what extent the Biden administration intends to use these types of pressure points in handling the relationship with Beijing. My sense is that they’d prefer to compete by investing in competitiveness domestically, restoring relationships abroad, and saving the stick for flagrant stuff. Biden could also reverse the EO immediately if he wished to. More importantly, taking a more careful approach in handling economic competition with China makes the Russia relationship less salient for Beijing, though it’s not going anywhere. It comes down to whether or not Congress is controlled by Democrats and how the bipartisan consensus on China policy develops. Without a growth breakthrough, Russia’s got a big problem attracting larger volumes of Chinese capital, especially if Russian locals keep protesting high-profile Chinese investments into the extractive sector at a time when their standards of living are stagnant or declining.

Mishustin and Putin’s instructions in hand, it looks like the General Prosecutor’s Office has taken the lead on reviewing firms’ adherence to the price control agreements struck in December to cap consumer price inflation for basic staples. The various prosecutors’ offices then share information collected with the now defanged Federal Anti-Monopoly Service, and act accordingly with their findings. They were doing so before the latest agreement — in just the first half of 2020, they reportedly discovered over 600 violations in terms of the legality of price formation among retailers and producers. So the story is really that Mishustin’s deal, at Putin’s behest, was a fig leaf to cover for existing activity trying to extract legal rents out of firms through the threat of extortion (they arrested 330 people for violations in 1H 2020) and the deal only increases the administrative pressure and resources brought to bear on one of Russia’s most competitive sectors. It’s a damning signal. The regime is set to use its law enforcement powers to attack businesses for setting prices in response to rational market forces when it’s politically convenient. They’re going to wish away inflation with handcuffs and fines.

Maxim Suraikin of the Communist Party is proposing a debt amnesty for all Russians up to 3 million rubles ($40,050) in the Duma. It’s unclear how far the idea will go. — debt amnesties are closer to existing policy preferences than direct cash relief and offers an economically significant stimulus, but would further add to uncertainty among businesses and households over the extension of bankruptcy moratoria from last year. The idea, however, gets weirder still when considering that as of December 1, there were 4.1 million Russians whose right to leave the country was curtailed due to debts owed, over 532,000 of which concerned alimony payments. Collectively, these people owe 1.6 trillion rubles ($21.36 billion). The amnesty would effectively cover most, if not all of that debt (depends on how much the individuals owe), and could provide considerable consumer stimulus headed into 2Q-3Q. But given how shaky the banking sector’s situation is with deposits and deep-seated concerns about macroeconomic stability, I can’t imagine the proposal getting far in its current form. Still, that it’s being debated is worth following. Further stimulus plans will be creative since no one in power seems to want to give people money.

COVID Status Report

Infections ticked up slightly to 24,246 — all due to an increase in Moscow — and recorded deaths rose to 518. Despite the plateau and slight decline in infection rates across the regions, it’s clear that infection levels are high in areas that are likely struggling to deliver adequate medical care and are at risk for prolonged recovery depending on the vaccine rollout and efficacy of vaccines:

The infection rate in the country’s breadbasket around the Kuban in the south continues to be the big worry since higher operating costs, interruptions for production, and so on increase the cost of consumer staples that are shipped internally across distances so large, they’re effectively imports in logistical terms. Fish are a notorious case — 70%+ are caught in the Far East and then shipped by rail westward — but the logic applies equally for wheat and other staples. It’s also an issue in the East, and due to the nature of buyers. For example, export volumes of grain from Novosibirsk oblast’ were up 24% year-on-year as of Christmas. Price differentials for exports vs. domestic sales, now price controlled in theory, create further skewed incentives for producers. Irina Shestakova, a former infectious disease specialist with MinZdrav, noted in an interview with RIA Novosti that she doesn’t think the situation with COVID will be cleared up globally until the middle of 2022 (though undoubtedly it will depending on where you live, the quality of medical care, and access to vaccines). The question is how that looks across Russia’s most remote regions in the year ahead.

Gimme the Loot

In the latest sign things could get (more) interesting in the Middle East, Qatar’s ruling Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani is attending today’s Gulf Arab summit in Saudi Arabia following a deal with Riyadh to reopen its airspace, land, and sea borders in a steady de-escalation of tensions that first erupted in 2017. Jared Kushner was involved in the talks and is reportedly attending today’s summit as well. On its face, it’s good news and a welcome sign that reason reigns supreme. But it’s a development that gets a lot weirder and more worrying when you dig into potential explanations for the context, as well as the factors driving why this rapprochement came together just before Biden’s inauguration and how little influence Russia actually has to dictate what comes next. As a brief aside, this week is likely going to continue to be foreign policy heavy simply because news in Russia offers slim pickings until Christmas — January 7 — passes.

One of the craziest stories lost in the shuffle during Trump’s first year in office was Rex Tillerson’s proactive role in trying to prevent an invasion of Qatar by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Fairly well sourced and corroborated by circumstantial evidence, the reporting from The Intercept went unnoticed because it’s easy to dismiss the outfit as a bunch of cranks. But this time, they struck gold. The silence about it in Washington speaks to just how successful Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been in lobbying, including establishing a direct line to Jared Kushner and through him, president Trump. The logic of the invasion plan was sketchy but believable — they reportedly wanted to seize Qatar’s wealth fund and assets since they couldn’t be safely offshored and escape their reach should the state fall — and the ostensibly failure of the effort to do so led to Mohammed bin Salman’s play to lock up royal family members in the Ritz-Carlton Riyadh and shaking them down for billions to save state finances from persistent low oil prices. So why was Jared Kushner involved in a face-saving deal right before Biden comes into office?

On the one hand, there’s the impression that the Saudis wanted a deal to show an incoming Biden administration that they aren’t bloodthirsty and want peace. But the logic seems more duplicitous. They give Kushner the appearance of a win and allow Trump to notch yet another deal in the region should he run again in 4 years (or, regardless, should he use his clout for political activity in his post-presidency) and they make it more difficult for Biden’s team to argue that Riyadh is responsible for escalating tensions in the Gulf. In effect, they’re handing Biden a hot potato because Iran’s decision to continue to increase uranium enrichment levels makes it harder diplomatically for anyone in Washington, Brussels, or other European capitals to argue that they can trust Tehran’s intentions to return to a deal. Yesterday’s tanker seizure further complicates it.

South Korean officials deny that their tanker was polluting water in the Persian Gulf and, after being accused of hostage taking in order to gain sanctions relief, a spokesman for the Iranian government — Ali Rabiei — said ““If anybody is to be called a hostage taker, it is the South Korean government that has taken our more than $7 billion hostage under a futile pretext.” It gets dicier still since it’s reported that Iran is trying to use assets tied up in a South Korean bank to cover the purchase of COVID vaccines. The US Navy immediately returned the carrier Nimitz to the region after announcing it would ship back to its home port. Yet with this going on, Iranian officials stressed that they wished to restore ties with Saudi Arabia if it would only change its regional behavior. The beat goes on. Notice Russia has virtually no role to play in mediating these disputes in the Gulf despite its ostensibly expanded diplomatic and military role in the region.

Energy rents are always at play, and the timing of the deal isn’t just about Trump leaving office, though that is most certainly the biggest accelerant. Qatar sells in the range of about 80% of its LNG exports to Asian markets and the rest to Europe. But export volumes slowed down in 4Q, responding partially to weaker European LNG demand as well as maintenance troubles at several trains from the country’s liquefaction plant, and Qatar’s probably realized it has a significant problem. Though it’s booking longer-term capacity at European import terminals, the gas outlook in Europe is dimming. Look at the IEA’s forecast for future gas demand growth by region. Ignore the full range. Deep blue is the Asia-Pacific and yellow is Europe:

Europe shows virtually no growth through 2025, so whatever capacity Qatargas books is directly competing with piped gas volumes over existing demand on top of competing with US LNG volumes that don’t have to transit the Suez Canal (and pay for passage). As relative demand falls in Japan and, eventually, South Korea, that means China’s power to price is only going to rise, especially since it already imports piped gas volumes at attractive prices and is expanding import capacity from Russia. So with COVID speeding up an off-ramp from natural gas as a ‘bridge fuel’, Qatar had to act. Furthermore, Qatar can’t circumvent exports via the Strait of Hormuz so in the end, presenting a unified front with other Gulf states responding to tanker seizures and attacks makes more sense in a market where it may be able to increase its exports, but faces marginal losses on prices and a declining share on its go-to auxiliary markets.

From the perspective of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Iran’s already called their bluff expanding export capacity to bypass the Strait of Hormuz by launching its own parallel pipeline and export terminal project via the port of Jask. Closing Hormuz was never a viable policy option. Not only would the US Navy and Air Force immediately retaliate, but Iran would lose revenues too. As export routes are multiplied, the economic risks of escalation are diminished, thus increasing the political appetite to take risks (within reason). At the same time, Gulf producers are facing a stark market reality with green energy:

As we can see, alternative energy historically underperformed broader markets per the MSCI, but if you look at RENIXX — a composite of the 30 largest renewable energy companies globally — equity valuations have surged back to levels last seen in 2008 when cross-border financial flows were much larger than they are now and oil prices were spiking towards $140 a barrel at one point over that summer. These stocks — and investor expectations — have surged during COVID when prices were in the tank, which would normally undermine fuel switching. Money’s being spent fast. There’s no point in waiting to calm things down with Qatar. COVID has shifted expectations about future earnings, the pressure on reform programs to diversify revenues (though not necessarily decouple from oil) has increased, and the only way to secure Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s position as regional leaders is by drawing in external powers, namely the US but also European allies of the United States with a vested interest in the region, to help.

Prior to the Obama years, it was US fears of energy insecurity and inflation that drove its military involvement. But the shale revolution took off the guardrails for aggressive US policy. Washington could afford to take risks it never could before because the market was oversupplied in a reliable manner. The irony of greater American energy independence is that it reduced perceived interdependence in the region. That’s what I think is so fascinating now to consider with Biden coming in and Russia still trying to figure out what it’s next “move” is. Assuming that tensions with Qatar are eased on a long-standing basis, every tanker incident or ballistic missile test from Iran becomes an ironically much weightier diplomatic tool to exert leverage on western capitals. Military action is seen as more palatable because it no longer entails the same types of cataclysmic risks for the oil market. Biden’s national security advisor Jake Sullivan has tipped the administration’s hand saying that Iran’s missile program, completely distinct from its nuclear program in the original Iran Deal, “has to be on the table” if the US is to re-enter any deal. In drawing this line, Biden’s team is effectively endorsing what the Gulf Summit intends to finalize: a permanent standoff between Iran and the rest of the Gulf backed by US sanctions and the threat of US military retaliation.

At the same time the United States is less energy dependent than ever and appears more wiling to take risks because of its internal political dynamics, Russia is more dependent on Gulf output than ever and stuck doing the same. There is on way Russia can drastically cut production to bring adequate balance to the oil market on a long-term basis like Saudi Arabia. It would lose too many wells from shut-ins, would lose billions in investments that are effectively being subsidized by the state directly or indirectly, see too many knock-on state orders affected, as well as currency weakness and a potential banking crisis. There is nothing, however, Russia can do to restrain regional actors from goading each other into military responses that would involve the US. The underlying contradiction of trying to be open to work with all sides is that if you get too deep into it, all sides can play you. It’s the problem the US faces, and one Russia has avoided only insofar as it’s actually not nearly as involved in the region as the US is despite the hype, with the exception of Syria.

When Putin signed off on elevating Aleksandr Novak to a deputy minister role in the cabinet and handed him the Gazprom and Rosneft policy file, he made it clear that managing the energy market is a dire political necessity for the sustainability of his political ambitions, support, and the macroeconomic stability of the Russian economy. We knew that, but COVID has elevated its significance further in the same way it has for Gulf oil & gas exporters. In practice, that means that Russia can only further commit to the Middle East as a means of managing the very risks that Russia’s initial interventions in Syria and Libya created. The first few months of the Biden administration are going to be a stressful period of probing what it is that the new team at the Pentagon intends to do. My suspicion is that while Biden’s cornered himself on Iran, he has a team in place that understood what Obama’s approach to the region was accomplishing in the longer-term. A greater role for Russia in the Middle East is a boon for the United States. It forces it to waste a growing share of its time and resources to manage conflicts it can’t resolve without help from others, keep an oil market it can’t manage from tanking, and make more enemies in time than it makes friends. The Gulf States are grabbing the loot of the last four years as Trump makes his way offstage. Russia could well find itself doing the same, but just trying to get a handle on the growing list of things it can’t control that it’s involved itself in across the region.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).