Sechin ain't a flak catcher

Rosneft's financials were upheld by Chinese prepayments, hiding the real state of affairs

Top of the Pops

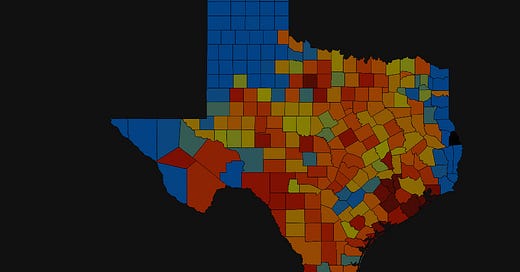

The Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) continues to botch handling the effect of severe cold weather on the grid as over a third of generating capacity remains offline. 4 million are without electricity. One Houston Chronicle piece went so far as to compare the failure to what caused the Soviet Union to collapse — underinvestment and mismanagement (alas, the opposite is technically true but we’ll spare them the headache of explaining that fact). The map of outages tells a story about planning hubris, one that I think is quite likely to bee picked up by the Biden administration in making its infrastructure bill sales pitch and one that may well reverberate globally as a result depending on the Federal response in the US:

Most of the areas at the edge of Texas experiencing no outages on this map — admittedly not 100% comprehensive — live in parts of the state that are hooked up to the Eastern and Western national grids. It’s a quirk of Texas’ obsession with state sovereignty, but also an outgrowth of its natural resource wealth. It’s high irony, then, that the state economy’s hydrocarbon wealth and dependence encouraged and shaped the political and policy environment such that most of Texas’ grid isn’t hooked up to national systems. That’s come back to bite them. It’s not just that wind power has taken a particular beating because of ice buildup on turbines, but that extreme weather outside of normal planning parameters, no thanks to global warming needed, has taken large volumes of natural gas, coal, and nuclear power offline as well as oil fields and refineries. This isn’t a story about renewables failing, it’s a story about the structural failure of a grid that was unnecessarily decoupled from other states and the lack of planning for redundancy and climate-proofing that has to take place to construct resilient systems. One of the next steps to emerge from BP and the European majors’ harder pivot on climate is tentative interest among oil & gas firms to explore if they can leverage their drilling expertise to get into geothermal. DoE just threw a $14.9 million grant at BHE Renewables and its efforts to extract lithium from geothermal brine, a dual-use of geothermal tech that would make it a much more sustainable source of baseload power in California. The lessons of Texas are about resiliency, redundancy, incorporating more extreme weather events into planning, and, crucially, finding ways of commercializing green energy to do something otters than just create energy so as to sustain multiple revenue streams and accelerate the adoption of frontier tech. Natural gas isn’t going anywhere fast, especially in Texas. But the trope that the cascading systemic failure reflects the pitfalls of renewables isn’t borne out by how many legacy hydrocarbon-powered systems have failed as well. If there’s any upside to this catastrophe, already responsible officially for 2 deaths with the expectation that more will follow, it’s that the hand-wringing about Biden’s war on oil & gas will run against the reality that it wasn’t just green energy that failed in crunch time. It was all of ERCOT and the complacency of grid management at the state level.

What’s going on?

Some experts now think that with the Central Bank’s shift to hawkish rhetoric despite holding the key rate at 4.25% while inflation rises will pressure banks to begin raising their rates on deposits. VTimes’ dive into the banks’ outlook is quite useful when thinking about the state of household finances. Last year, banks showed significant signs of strain as deposits were withdrawn, though the CBR managed to hold it all together without serious incident and foreign cash reserves from SOEs were forked over by government diktat to maintain reserve needs in the banking sector. But the shift for banks worried about their own solvency during the recovery, even if minimal, will pull more money out of circulation to be spent on goods and services. I’m not sure that a drop in the velocity of money circulating has a significant impact on inflation as a counter-weight because most of the inflationary pressure in the economy at the moment is from clear supply/demand mismatches and the influence of global inflationary pressures on commodities. It’s good news for anyone who has money to save at the moment, and it’s important for banks competing for market share since they want their customers to hold more money with them (and therefore backstop more lending). It’s just not going to be enough to make a big dent for awhile unless the rates go up considerably and the cost of credit rises in the real economy to reflect actual default risks in a ‘normal’ interest rate regime for Russia rather than the state-subsidized, lower-rate environment that the market now expects will be eased out slowly going into 2022. If you don’t have savings, well, who cares?

PWC’s report out on the state of the global freelancer economy shows that the recovery in Russia and future economic services growth have a serious problem. According to the data collected, Russia is in the top-5 countries globally when it comes to the size of the market for freelance services, but the issue is how many freelancers there are. Left to right, this shows the US, India, Canada, UK and Russia:

Blue = number of freelancers (mlns) Beige = market size (US$ blns)

In nominal terms, the size of the freelancer economy — $41 billion — is equivalent to about 2.4% of GDP, a fair bit lower than the $60+ billion officially spent on defense (the actual figure is undoubtedly higher if you try to pick apart cross-subsidies and dual use spending). 14 million people represent around 19.3% of Russia’s labor force doing work as a self-identified freelancer — that’s not far off the 20.6% of the labor force who report working in the informal sector per Rosstat data from 2019. 14 million people fighting over $41 billion comes out to about $2928 per freelancer if we divide up the pie evenly, which is real money but complicated by the fact that freelancers are likely clustered in the most expensive cities, many are augmenting income part-time and the distribution of earnings is most likely quite skewed, and the service sector only accounts for about a fifth of the value the economy creates. The number of freelancers keeps rising just as the size of the labor force has declined from its 2009 peak by nearly 4 million people, which also reflects that net job creation vanished a few years ago. Companies have to increase their spends on stuff like advertising and consumers need to be able to buy more products to keep a hefty chunk of that activity profitable, otherwise the gig economy will start distorting what we’re seeing in the labor data — and hiding the extent of problems because of cost of living adjustments, inflation, and the lack of a clear line between the formal and informal sectors for some of this work, especially since wages have to rise to retain labor if the labor force continues its underlying trend, which ends up negatively affecting older Russians if inflation increases as a result.

Rosstat’s at it again jury-rigging 4Q data for industrial output and performance in the Russian economy to make things look better than they are since they complicate any attempt to compare like with like. Initial data showed a 2.5% decline in output for manufacturing year-on-year for January 2021. But December reportedly showed 2.1% growth on the month per new methodological standards. The claim now is that the December uptick vs. January is because of the coincidence of several one-off factors — a bunch of state contracts rushed out the door in 4Q (frankly, a common occurrence), conditions around the pandemic, people taking different holidays and the New Year. The following sets January 2019 as the base:

Black = general production volume Beige = excluding seasonal/calendar factors Red = trend

Basically, industrial output is stagnant at best for now, and while Rosstat is now promising to stop changing its methodology so much. Weather is also to blame as January 2021 was far colder than past years, but it’s hard to shake the feeling that the government’s accepted lower output, which directly correlates to oil production cuts and assumes it’ll unwind by itself by the second half of the year as the oil market is now balanced per Aleksandr Novak’s estimation. This should seriously worry the Kremlin for 3-4Q and campaign season. Normal output levels pre-COVID weren’t generating much economic dynamism…

Putin is apparently set to sign a law that would amend the tax code to give the Federal Tax Service (FNS) the power to assess tax liabilities for Russian firms importing goods whose prices are set on international exchanges — think oil, precious metals, rare earth metals, minerals, etc. On its face, this doesn’t seem like that important a story since Russia’s a commodity exporter rich in most of the items covered. The real aim of the change is to allow the FNS to assess taxes based on market prices rather than the internal transfer prices that importers use with established trading arms abroad to shift around costs — and profits — to minimize tax exposure. The gap in pricing isn’t generally that large, but it’s possible that large deals become economically unattractive when higher prices are factored in for tax burdens. Either way, it’s a theoretically positive step for the business environment — firms have a more reliable legal framework to assess the tax implications of any deal, and the FNS is opening the door to deepening cooperation with foreign governments when assessing international deals. That’s a net positive for business, the catch of course being that it has little to no bearing on the broader problems in the business climate and will likely cost Russian firms trying to free-ride on transfer prices a bit of money, thus raising revenues for the current round of fiscal consolidation.

COVID Status Report

Daily cases fell to 13,233 and reported deaths rose to 459. The government has extended its ban on flights to the UK, presumably to prevent more cases of the Kent strain, but more importantly, the gap between what we know about the success of Russian public health efforts and the infection data seems wider now than it was a few weeks ago:

The week-on-week decline reached 10.5% yesterday, and the current drop-off is far more pronounced than last summer when restrictions were largely responsible. As Jake Cordell notes, we’ve only got regional data to look at for vaccinations — there is no national data — and the current rate of vaccinations suggests 70% of all Russians would be vaccinated my December 2022. That could reflect the government funneling vaccines abroad instead of helping its own people, something that would be on brand for sure. There may also be supply bottlenecks we aren’t that aware of due to the lack of transparency. What doesn’t make sense regardless, however, is the current rate of decline if restrictions are being eased steadily and the vaccine isn’t going out fast enough. The government officially can’t explain why the death rate was so high this last year during the pandemic according to Nezavisimaya Gazeta. Everyone knows they lied last year, the question is how pervasive the statistical fraud is now. Clearly it’s systemic and part of the ‘recovery plan’.

Till the Money Runs Out

Rosneft has apparently resumed an old practice popularized during the halcyon days of Brent prices at $100+ a barrel: it’s selling barrels of oil to Chinese counterparties that haven’t been extracted yet. It’s an old trick Sechin used when financing the acquisition of TNK-BP. Agree to huge prepayments for future deliveries in what’s ostensibly a long-term contract to be honored. A significant part of how Rosneft managed to deliver the results it did last year — and fool investors into holding onto the stock while IOC competitors crashed — was that it received $12.8 billion in pre-payments in 4Q, with 20% of the volumes purchased to be delivered in the next 12 months. This really gets to a quirk of Rosneft’s business model that was originally meant to capitalize on long-term demand growth expectations and also use prepayments to lift crude volumes from Kurdistan and Libya to redirect Europe-bound crude flows to China so he could take on the Saudis for market share. Sechin loved to reiterate his belief that long-term supply contracts were the best basis to establish secure and profitable relationships for the company and the oil sector. China bailed out the company presumably by locking in lower prices for long-term deliveries in exchange for the upfront payment, something BP might also want to thank them for. The prepayments allowed Rosneft to reduce its effective debt burden to $45.6 billion, worth 62% of its current market cap (roughly $75 billion after it overtook Gazprom on Russian exchanges). So here we see that Rosneft actually did very little to earn its earnings windfall in 4Q, once more reiterating that the company isn’t actually that well run and reliant on political support, tax exemptions, and state spending to support Sechin’s personal ambitions to expand Rosneft’s reach everywhere he can without any regard for its core competencies. Another layer of crazy: after meeting with Putin to report on the company’s 2020 financials and big up his ‘great success’, Sechin has requested 300,000 doses of Sputnik-V to vaccinate his employees from MinZdrav. That’s more than St. Petersburg has received thus far, and an insane logistical strain based on the vaccination data we have available.

Suffice it to say that one of the reasons Rosneft can readily demand these types of resources is because of how integral it is to the maintenance of Sino-Russian relations and the national balance of payments, even if it stupidly swapped US dollar contracts for Euros. These international deals, in the context of Russia’s political economy, are part and parcel of how domestic political constituencies, blocs, and individuals make themselves invaluable and their fiefdoms ‘first among equals.’ Whatever the limitations of Russia’s economic engagement with China — it has to resolve scores of institutional barriers to Chinese investment if it wants a more sustainable, even 'partnership’ — China remains the world’s swing consumer of oil. Rosneft was the first in the door among Russia’s SOEs and largest firms to expand its market share going back to the 2013 mega deal that actually mimicked much of what Khodorkovsky had negotiated when he still headed Yukos as of 2002-2003. Despite the current euphoria about prices, crude oil stocks globally are still 200 million barrels over their three-year average and there are growing questions about China’s oil demand and its role as a market manager. Choosing to take up long-term, prepaid supplies from Rosneft only adds to them.

The US holds about 600 million barrels of oil in strategic stocks with strict legal limits on when they can be drawn. China currently holds somewhere in the range of 400 million barrels of oil in reserves and allows itself to release them to influence prices when convenient. Though stocks were drawn down in December, most don’t expect that trend to continue. What’s likelier to happen is that Chinese importers will make use of contracts like those they cut with Rosneft to hedge against price increases and release supplies to the market to put downward pressure on prices if OPEC+ cuts end up having a stronger effect than expected by summer so as to smooth out the curve on the price increase. Rosneft is, therefore, just one of many pawns in a game played by the world’s leading oil importer on what remains, overall, a buyer’s market. The rise in oil prices taken in light of price trends the last decade is still not that significant and the slack in demand creates opportunities to hedge against expected price increases:

The record cashflows Rosneft recorded starting in 3Q probably reflected supply hedging from Chinese counterparties awash in cash, but also point to a bigger question about what’s happening in the Chinese economy during its current recovery — and therefore how that affects the arc of the oil market in the year ahead. The growth of the oil future market in China — up 20+% year-on-year for yuan-denominated oil contracts — points not to hedging real economic activity, but a growing speculative bubble that parallels a broader increase in speculative activity across the economy since the growth in futures doesn’t correspond to concerns about market volatility as expressed broadly elsewhere. In other words, Chinese suppliers were locking in cheap(er) oil and shoving money out front to Rosneft, but the futures market, ostensibly meant to allow importers to further hedge against price fluctuations, suggests that a financial frenzy is ripping across large parts of the Chinese economy, and therefore likely underpinning a chunk of consumption that would take a hit should the bubble burst. Rosneft was locking in long-term deals without any substantive consideration for what China’s growth actually consists of. And as is often the case with rising levels of financialization, the real economy will feel the pain — Rosneft included, if in delayed fashion — and the financiers will probably find a way to make out alright.

Credit growth in China hit $5 trillion for 2020, a 35% increase year-on-year. Beijing’s response has been to slowly reduce the flow of credit and capital into real estate, but that’s insane. That’s nearly a third of the total increase in global debt last year. China’s overseas lending is also at a nadir now:

To be fair, the Rosneft deal is essentially a loan to be repaid in physical production. It apes a long history of equity/credit for resource transactions Chinese firms have reached in other resource-exporting economies. But if China’s loaning less abroad — nearly all of these loans are in USD — it’s not as actively financing recovery of investment or consumption levels elsewhere while managing an appreciating currency due to a surge of capital inflows that makes it cheaper to buy commodities like oil in relative terms for domestic importers that the government has sought to maintain to shore up domestic balance sheets after the financial pressures of Trump’s trade war and trying to avoid a currency appreciation that would weaken Chinese exporters. That surge, however, is bound to make a market saturated with dumb money all the dumber as the recipients of inflows will eventually turn around and start looking abroad for opportunities as the domestic market struggles to absorb yet another round of infrastructure investment that’s not generating real value or return in order to make use of improved balance sheets. These are all indirect ways of saying that Rosneft’s closing long-term deals with a consumer that’s structurally gutting its own ability to grow oil demand through imbalanced speculation, lack of demand-side policies, the strains of financial liberalization, and its long-run environmental policies. Rampant speculation doesn’t generate that much demand growth in the real economy, save for construction if we’re talking about property. It can increase incomes, but those incomes usually reflect the distribution of asset ownership. China’s millennials are seeing their prospects diminish as costs of living rise.

Sechin was lucky to be able to close a big deal with prices in the toilet to bail out his financials and make the boss happy. It helped secure his right to make demands of the vaccine rollout that could drastically skew the arrival of sorely needed doses in Russia’s regions given Putin’s consistent desire to maintain close ties with Xi Jinping and the value of having a partner in Beijing publicly back the regime against the current wave of protests. The deals, however, fit into a bigger picture whereby China’s growth is increasingly unstable, not structured in a way that will sustain greater consumption of oil, and the economy maintains the capacity to have a large effect on prices through crude oil drawdowns that, strategically timed, would allow importers who know companies like Rosneft are desperate for cashflow to lock in long-term deals on favorable terms amidst what many assume will be a bull market for oil over the next few years. He should count his lucky stars. He’s in till the money runs out. It’s impossible to hide what’s going on with financial trickery forever. That’s when he gets really dangerous for domestic politics.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).