Top of the Pops

Hyundai just announced plans to sell a million EVs globally by 2025 off of its new platform, a modest sales target. What’s eye-catching are the stats they’ve trotted out for the platform: 80% charge in 18 minutes, a 500 km range on a single charge, and you can add about 100 km of range with just 5 minutes’ charge. The timing is key. No one wants to be forced on a road trip to spend half an hour or more waiting at a rest station in Western Pennsylvania or Doncaster or Bochum before moving on. Once you get charging times into the 15-20 minutes window, filling stations can more successfully pivot to improve their margins offering food, conveniences, and so on. Volkswagen has already announced its own EV platform — think the structural guts and chassis upon which multiple models can be developed — and that’s pretty clearly taking off with auto manufacturers trying to find growth amid the current consumption downturn. The question now is when does the tipping point come? Switching to EVs isn’t the same as adopting the internet, using smartphones, and the like. EVs are repeating a function already fully provided by another product without offering anything substantively new, save that they’re cleaner. But history shows that at an adoption rate around 5%, technologies tend to massively accelerate as businesses and consumers realize the benefits and how to profit:

There are countless logistical hurdles left to clear. It’s just telling that when consumers really want something, policymakers and markets have proven adept at following in the past.

What’s going on?

Rosneft has reached a deal (without publicly available specifics) with Eduard Khudainatov’s Neftegazholding to acquire the Paiyakhi oilfield and formally incorporate it into the Vostok Oil project. Estimates stand at $5 billion for the transaction with payment coming in a mix of cash and equity stakes or else full ownership of other assets. The numbers cited on premiums and tax breaks per barrel are a wash and not helpful to make sense of the deal, I think. More interesting is word from Rosneft that they intend to sell brownfield assets, including potentially projects on Sakhalin island (and its coastal shelf), Western Siberia, the Volga-Urals basin, even Timanoo-Pechora. Looks like the OPEC+ deal is now creating an unintended effect: large producers like Rosneft particularly beholden to the cuts can reduce their tax burdens by focusing on Arctic projects with a long list of exemptions or state support. It’s quite early, but it’s possible that smaller producers might be the big beneficiaries, which will then further complicate cut adherence by broadening the pool of firms who will no doubt lobby to maintain their investment plans, especially if they’re grabbing depleted fields on the cheap and have to pump more today to realize returns.

Russia’s Central Bank is now worried about the rapidly growing number of Russians who are investing into equities through brokers rather than using money managers. As much as 2/3 of all investors are using brokers and directing their funds personally. The real problem is that these investment instruments and options to invest are still developing and new, so everyone’s free to try and chase returns while bank deposits offer them nothing against annual inflation. Here’s the October MSCI snapshot again next to emerging markets for annual performance:

Russia’s annual performance for returns from its mid and large cap firms shows great potential to those willing to tough out the deep troughs. But the market follows a clearly political arc, from sanctions risks encouraging more domestic capital to be deployed into Russian equities to national spending plans to the exaggerated impact of oil shocks worsened by the construction of the fiscal system and ways in which wealth is taxed and redistributed. Volatility is a much bigger problem for Russia’s growing class of self-starter investors than for those in the US worried about Robinhood addicts.

Vedomosti’s interview with EN+ head Mikhail Khardikov captures the challenge facing the electricity generation sector during the COVID shock very well. Power demand in Siberia only dropped about 1.4% off of pre-COVID levels, but declined 10% in the Urals at one point. Regional segmentation within Russia due to local climate and economies is a broad problem for firms like EN+ planning at exit from the current crisis. Revenues haven’t slumped as much as feared on the whole, but that’s also cause non-payments for utilities peaked in April, dropped considerably, and started rising again with the current wave of the pandemic (up 12% for October). This has the a quietly building potential for social crisis in many regions with harsh climates because demand for electricity is quite inelastic and only going to grow. This means you need massive spending to improve energy efficiency — again, more difficult in harsh climates — and also into new generating capacity. In Khardikov’s own words, long-term project financing doesn’t work in Russia because of byzantine pricing rules and tariff regulations, quota systems for planned investments that make sense for a centralized system but create tensions planning at the regional level, and more. Without it, costs are going to go up from interruptions and shortages in investment cycles worsened by the current crisis.

MinFin is finally going to launch a centralized government platform linked to the Unified Information System (UIS) collecting relevant data on confiscated properties working with Rosimushchestvo. The object is simple. It’ll be harder for state officials and the rich to cut inside deals using their connections to acquire valuable assets on the cheap, to self-deal, or else use confiscation as a business strategy against competitors. The real catch is that the project would give figures in Moscow’s economic/budget bloc in Moscow, including Alexei Kudrin, a means of naming and shaming to push back against brazen raiding, particularly by security officials. For 2017, the Audit Chamber found that costs of selling off these properties exceeded revenues by 42 million rubles ($555,240) with the overall margin 222 million rubles ($2.93 million) to 180 million rubles ($2.38). Someone’s lowballing the property values if that’s the case…

COVID Status Report

Cases fell back towards 25,000 for the last 24 hours with 589 recorded deaths. It looks like Moscow’s starting to get a better grip on the virus. However, cases in the regions ticked up slightly again:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

The Sberbank subsidiary “Immunotehknologii” won a tender to be the sole supplier for COVID vaccines in Russia, which has to make German Gref happy as a clam. As of now, Mishustin, MinZdrav, and MinFin appear to smoothing it over with the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service and those who rightly point out that it’ll lead to cost inflation and undermines efforts to improve procurement processes. Getting people vaccinated has to be a priority, though. Putin had to call off personal meetings today with Alexei Kudrin (reportedly now infected) and Valentina Matvienko from the Federation Council to take precautions. The sheer number of political figures in Russia who’ve been infected is something the Kremlin needs to sort out fast, lest it be stuck finding replacements in the spring.

They Might Be Giants

The discourse around leading firms as “national champions” has countless applications, but was most firmly rooted in the rise of state-owned enterprises ceasing control over nations’ resource wealth to more directly transfer the gains from any rents they provided to the state’s budget and its people. An entire literature arose out of the concept of the ‘obsolescing bargain’ between foreign, multinational firms trying to extract said resources (or provide production) and governments being able to renegotiate the terms of that firm’s continued presence in the country, raising the relative costs of operations until, theoretically, a local firm could supplant it. That theory, of course, was totally wrong because it was built out of the OPEC oil shock in 73’. Commodity price cycles felt forever changed by the rise of oil scarcity as a mentality. And it failed to account for how intellectual property, internal markets within corporations, transfer pricing, the ability to access international credit, and more could allow those firms to retain their privileged position negotiating with governments in developing countries. It’s important to also consider the inverse: what happens when national champions that have “won” domestically lose out?

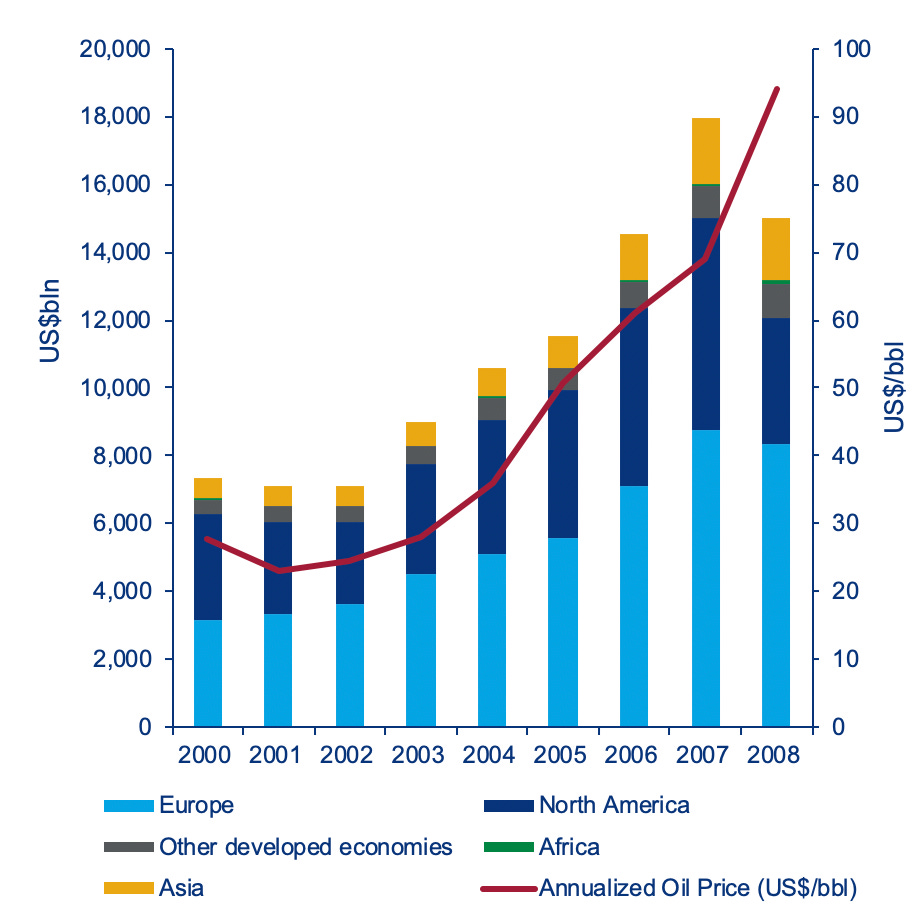

In Russia’s case, the 2000 commodities boom shaped the story. After the re-nationalization of Gazprom and Yukos was stripped for parts and largely given to Rosneft, Russia’s economic prestige was linked with the market cap of its biggest energy firms. The narrative — and political power vested into those firms and personal networks — were shaped by the explosion of FDI globally that decade underpinning a mix of rising demand expectations and a slowdown in the rate of new production coming on stream in the business cycle from 2005-2007. The following show net stocks of outwards FDI (glad I had this chart handy…):

Before the last crisis, some dreamed of Gazprom becoming a $1 trillion company as oil & gas looked promising. As we all know now, that never came to pass. Tech is the hamburger that’s eaten the equity world. Consider the following market cap valuations in US$ blns:

The national champion model for energy in Russia began to fizzle out in 2008, but really died in the aftermath of the crisis because of the US Federal Reserve. Shale as a whole returned a net negative cash flow in the hundreds of billions of dollars covered largely by junk debt, which demolished any equity case for Russia’s oil & gas champions to seize the day ever again.

Don’t get me wrong. Rosneft and Gazprom are still Russia’s biggest tax revenue generators, they hold immense sway over a wide range of procurement contracts, and have leading roles handling Russia’s foreign relations with the European Union and China. But Russia’s current landscape for “national champions” has further shifted because of COVID and it’s clearly Sber that’s racing to exploit the opportunity. German Gref’s realized a basic reality of the tech world that oil & gas firms in Russia used to lean on: the first in able to consolidate their market position build up a relatively unassailable position that increases barriers to market entry and reduces competition. Whereas oil & gas companies once assumed that sitting on the single most important fixed asset resource in the world would protect them, now it’s building out leads when it comes to scale. At a certain size, you can afford to pick off innovative competitors starting out with acquisitions and it’s clear that Gref’s ambition is to corner the Russian market for e-commerce and consumer services, from which the company could conceivably then tentatively expand elsewhere. Much of this is also branding. Banks risk losing customers to tech service providers and Russian consumers could well abandon ship if Sber doesn’t get it right. It’s clear that Sber, Russia’s largest bank and increasingly its most impressive SOE, is well-positioned to use its dominance in its traditional core sector to change it up.

Where I think it’s worth thinking more deeply about Sber is what it can do that Rosneft and Gazprom can’t do, and what that says about the structure of domestic political competition between SOEs and the significance of Russia’s “national champions” post-COVID. The fact that Sber could very well be the future lodestar for success among Russia’s state-owned and parastatal corporates, I argue, comes down entirely to it being a financial entity responsible for achieving social objectives that the state refuses to finance directly and for sustaining consumer demand. The surplus/deficits are measured in billions of rubles:

MinFin hides how important the oil & gas sector through a variety of tricks, including breaking out their VAT payments from taxes levied directly on the production and export. However, showing the relative ratio of direct levies to VAT receipts offers a snapshot of the slow but steady shift towards increasing the tax burden on consumption. VAT receipts overtook oil & gas taxation in May-June during the worst of the first wave. The broader point now is that oil & gas companies in Russia have been constrained by the regime’s obsolescing fiscal bargain. The tax code’s burdensome requirements and progressive nature have reduced the sector’s competitiveness and limited its ability to invest into new output, a strategy that worked when the world looked it did from 2000-2008 for commodities. But ever since, the link between FDI, global growth, and demand changed alongside the equity bubble (and hole) created by US shale:

The rate of demand growth slowed a bit, FDI stock growth rates were considerably lower, and with weakening productivity gains in emerging markets and economic malaise in the EU, that meant debt was also integral to sustaining oil demand. The current COVID shock has forced the Russian state to collect more revenues from consumption and incomes and to improve tax enforcement to make up for the obsolescence of that bargain. Sber is one of the unintended beneficiaries politically from the constant return to budget surpluses since those surpluses generally correspond to demand constraint and rising levels of person indebtedness over time given real income declines and stagnation. It falls to the banks to keep the cost of borrowing from rising too much while improving financial services since they’re now in higher demand and need.

This isn’t to say that Sber and German Gref are somehow on track to dethrone Igor Sechin or the oil & gas sector’s continued central role for the country’s politics. After all, MinFin is raising the tax burden again on the oil & gas sector to accelerate fiscal consolidation 2.0. But the more Sber diversifies into other areas and is able to generate rents, not by policy fiat but by its sheer size and access to resources, the less dependent it is on interest income to sustain its financial health (and I’m sure they’re going to get creative moving money between divisions depending on their needs). The less dependent on interest they become, the more able they are to sustain lower interest rates for the longer-term while the Central Bank rethinks its own policies to guide Russia through the next few years. The energy firm data is from April (had it on hand) whereas Sber is from September, but it makes an important point about financialization in the Russian economy given its current stagnation. These are quick hit numbers:

Sber is worth more than either Rosneft or Gazprom, and the market capitalization gap is only going to widen if it truly moves into tech since it’s a story investors like and it’s also a market that produces new kinds of rents the business can realize, particularly with data. This is the key point. Sber’s assets are driven by lending since those loans generate income for Sber, but more importantly, generate economic activity throughout the economy. Rosneft and Gazprom’s assets generate activity, but generally depreciate in value much more quickly or else are hostage to commodity price fluctuations and their liabilities are debts owed to banks like Sber. Sber’s liabilities are the money held from depositors or else money borrowed from the Central Bank or other banks trying to keep the system operating. Even though Russia’s macroeconomic policy is not designed to do so, it’s an inevitable fact of the need to raise taxes on consumption that banks are going to matter more to keep consumption going for the sake of the fiscal health of the state and, as a corollary, investor expectations around the ruble. Whereas oil & gas are trapped by the limits of fixed assets and physically owning things, Sber has the benefit of trying to move into a high growth market in Russia while profiting off of any and all economic activity if it lends accordingly. I don’t think Gref is ever going to “take on” the siloviki, but there’s a reason Sber is opening up shop in the UAE. Sber suddenly becomes a financial middleman for a wide variety of commodity-sector investments and trades while also establishing a foothold in a non-Western financial center.

The company’s rolled out AI as a core part of its earnings model, already accounting for 6% of its net profits this year via efficiency gains and productivity improvements generating more earnings on an estimated return of 100 rubles for every 15 rubles invested into AI. With the aim of making all processes fully AI-run, Sber is going to wring out more cash from its existing base, free up more capital in the wake of the failed deal with Yandex to become king of online commerce and retail, and more. NOCs aren’t going to suddenly lose their clout because of the energy transition, but in a system simultaneously so dependent on the oil price and commodities markets while also so diversified with a deepening financial market, other players are going to have a larger say. Sber is an interesting business story to follow, yes. But it’s more than that. It’s showing us in real time what the shift in power between energy, tech, and finance in a country like Russia means for politics. In this case, the message is murky but clearing up: the devil’s bargain with Russia’s biggest energy firms isn’t over, but it’s a depreciating asset.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).