Top of the Pops

The Director of National Intelligence dropped an unclassified report yesterday confirming that the US intelligence community believes that Putin personally authorized an array of influence operations intended to support Trump’s re-election, though these efforts did not include attempts to directly hack election infrastructure. Sanctions are expected shortly, and while Biden is saber rattling over making Putin pay, I do not expect new sectoral sanctions or anything touching sovereign debt to be unveiled, but rather targeting individuals or defense/security adjacent organizations. The timing is a bit more sensitive than usual for macro risks despite Russian markets’ general imperviousness to sanctions because of the Central Bank’s inflation-induced pivot to raise rates faster and more aggressively. The spike is already reflected in the spread between MosPrime Rates and forward rates for ruble deposits:

Any time people get spooked about sovereign debt or other broad-brush sanctions on top of rising inflation concerns, you can see yields for bonds and other related instruments rise to offset the loss on future cash flows due to higher inflation or default risks. I don’t have access to today’s market data for CDS or bonds, but the money market is still a helpful reference point for how much inflation expectations are beginning to affect real rates across the economy. Deposit rates have to rise to keep pace with inflation and maintain reserve adequacy ratios, particularly if Russians are now more comfortable tossing money into retail investing in hopes of extracting value from stocks. There’s never been significant appetite at the US Treasury to sanction Russian debt because doing so would not only be an insane escalation of economic war, but would boomerang back on the US since it’d force Russia to 1) further deepen its domestic market’s ability to absorb debt issuances, which improves its ability to weather sanctions 2) turn to China and expand their bilateral financial infrastructure without much the Treasury could do to stop it. I don’t think any new sanctions announcements will be that impactful and rather will target domestic audiences in the US so long as Biden listens to the Treasury. Inflation’s doing damage damage without any help from Washington.

What’s going on?

The upcoming release of the Audit Chamber’s 2020 review — set for the Duma on April 7 as of now — is expected to give Aleksei Kudrin another excuse to politely excoriate the government for its handling of financing and spending priorities during the crisis. To some extent, these reviews are a greatest hits parade for Kudrin — construction works are left incomplete inexplicably, state procurement rules are violated, vast sums are wasted by inefficient spending and price manipulation, and so on. What makes this slightly different is the context in which the criticism will be taking place. Things aren’t just stagnant, they’re looking bad because they’re stagnant amid rising inflation. One of the biggest gripes coming out of the Chamber is that there is no effective coordination between the strategy/guiding documents for policies intended to increase labor productivity and the institutional structure meant to implement the policy. This really sticks out to me because it’s not like building more roads or housing or can indicator that can be improved through targeted spending on healthcare or a boost to pensions. Labor productivity reflects structural dynamics, including a refusal to countenance any short-run increase in unemployment from inefficient sectors. It’s clear that the national projects have become a punchline and not a policy agenda despite the pretensions surrounding the 2018 inauguration. I’m interested to see which bits Kudrin targets in criticizing the reappropriation of funds from national projects to anti-crisis measures, particularly since it’s clear the state could have afforded to further borrow without meaningful political or macroeconomic risks.

A PwC survey shows that globally, firms have significantly improved their technological capabilities between 2018 and 2020, showing a significant decline in concerns over the availability of opportunities to use tech to improve (and measure) productivity. Conversely, now the trouble is that the tech they have in hand is often seen as too complex. The following are % of firms responding to the survey on barriers for the measurement of productivity:

Descending: lack of tech, resistance from employees, lack of resources, tech is too complex, no problems, everything’s already implemented

These measurements and PwC’s rationale for much of this study correlate to the rise freelancer economy as younger workers lack high-paying opportunities or else want to supplement their income and work more flexibly. The number of firms confident they can attract freelancers rose from 39% to 80%. PwC estimates that the number of project-specific workers i.e. workers on contract for projects rather than full or part-time in developed countries will rise from 5% to 15-20% within 5 years. These trends are as pertinent to follow in Russia since younger workers have turned to freelancing in response to a terrible economy. Deputy Minister and ‘social bloc’ leader Tatiana Golikova took a shot at Generation Z yesterday noting that the jobs market doesn’t fit Gen Z’s needs, insinuating openly that they face higher levels of unemployment because they’re too choosy and demanding. Alas, she’s wrong. There simply aren’t enough good opportunities and the companies able to more flexibly create project work seamlessly while liking generating rents by dominating local, regional, or national markets will benefit in the years ahead.

This longer-read on forestry from Vedomosti is worth a read if you have the time, but is an interesting case of a failed attempt to stimulate private investment and activity by allowing private property owners to grow and fell trees freely as of September last year. The catch is that only 0.03% of all available land to do so was actually being put to use after the law was changed. Problems like this can be traced back to the byzantine and uneven privatization and de/re-regulation processes of the 1990s and early 2000s. Historically, it was only state-owned forests that could be used for this purpose since they were held in a public trust — the State Forest Fund — and that way, the state could extract more regulatory rents as well as more easily regulate sector activity (which makes a lot of sense for natural resources like forests). The privately held land on which forests were located was broadly designated as agricultural land i.e. it could only be used for agricultural purposes, effectively banning private forestry. Now that the Kremlin’s in dire need of new sources of business investment, domestic value-added production, and export revenues, reform has come. For now, most of the plots that could be exploited are too small to interest big investors, so we have to see more consolidation of ownership of the relevant land available. There’s a lot to unpack here, the most interesting of which is that the steady rise of wood prices makes investments into forestry a potentially useful pensions instrument in Russia given its immense forest wealth — think of Real Estate Investment Trusts that pass on the vast majority of their profits to shareholders as a reference. I need to dive deeper into this sometime, the craziest institutional stories in Russia almost always come from markets like this that are liminally trapped between the state and private interests without effective resolution, such as cemeteries (85% of which have no legal owner in Russia…).

MinEnergo has replied to the Audit Chamber calming fears of a looming motor fuel crisis due to shortages, citing evidence that existing measures including the recent hike on the crude oil export tariff have stabilized prices. The precedent cited by the Audit Chamber comes from 2018 when oil prices rose in the wake of the Trump administration’s reimposition of sanctions on Iran and escalating sanctions on Venezuelan crude supplies. Higher prices naturally filter into the prices refiners quote wholesale retailers for refined products. The big policy move to head off the phenomenon was an agreement with the government at the start of the year to provide 50 billion rubles ($684 million) of relief to refiners to increase production and limit the pass-through effect of price increases. The current “damping” mechanism for refiners is used to offset any losses from the political agreement to hold down consumer costs in response to the rising tax burden on oil extraction, which raises gate prices for refiners since the tax has been levied before they buy the oil (unlike the export duty). It arose in 2018 as part of the political compromise to offset this problem in the first place, and clearly it doesn’t work particularly well without ‘manual’ adjustments on an ad hoc basis. Fortunately, oil prices are no longer climber on irrational exuberance about demand and the situation’s under control.

COVID Status Report

There isn’t much of interest on the virus today, so I’m taking this excuse to instead react to the fallout from a crisis measure now hitting the economy: a looming apartment shortage. The Minister of Construction and Communal Utilities Irek Faizullin warned on Tuesday that the national supply of new apartments has been exhausted and demand for new-builds is outpacing supply. Net construction of new-builds fell 5.9% last year amid an explosion of demand fueled by mortgage subsidies. Mortgage issuances were up 40% for Jan.-Feb., rising past 600 billion rubles ($8.15 billion). In cities of a million people or more, apartment prices are on average 15.7% higher than they were a year ago, massively outpacing topline inflation. The irony of course is that the longer the current policy offering fixed-rate mortgages at 6.5% is held in place while inflation rises, the more attractive it is to borrow. All of the worst hit regions — Bashkortostan, Krasnodar, Perm’, the Altai, and Satarov — are exposed in various ways to commodity export sectors, underdevelopment of infrastructure, and wage and income dynamics lagging the main metropoles in Moscow and St. Petersburg or the income levels we see in the main oil provinces that somewhat offset higher costs of living. This is a problem in the regions, not just the urban centers where regime support is weaker anyway. What’s remarkable about this shift on the market is that the mortgage subsidies are no longer the price driver, it’s the physical shortfall of housing stock. But they created a ‘bridge’ for demand that tipped into market imbalance this year because they didn’t address other aspects of the virus response adequately via income support, getting the caseload under control, etc. In other words, the supply-side mortgage policy — I argue that the supply of credit here was the main ‘policy lever’ rather than generating demand since that demand was repressed by falling incomes — created more economic instability despite the intention to stabilize the economy.

The Price ain’t Right

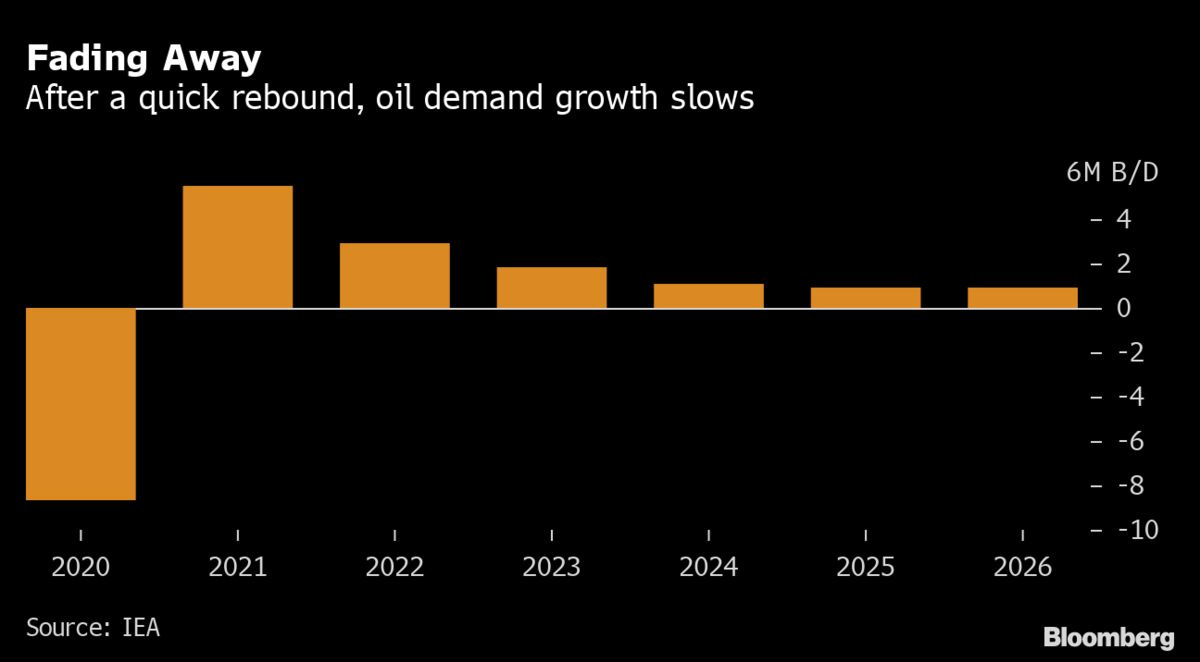

If Moscow is betting on further oil price gains, it’d better rethink its strategy. The IEA has come out with a new forecast on oil demand recovery that supports my long-held view that the pathway to pre-COVID demand levels was long, arduous, and would provide enough of a window for marginal demand decreases to begin to take effect to threaten any future growth:

Their guiding assumption is that demand growth will never return to its pre-COVID trajectory, which was already showing structural decline post-2015, further weighed down by Trump’s trade war with China (that hasn’t ended, lest we forget). Pre-COVID demand levels return by 2023. This is all the more important to remember because of the lopsided nature of the global recovery. The US is doing all the heavy lifting, and if Democrats manage to pass an infrastructure bill now that they’re reportedly moving towards at least amending if not killing the filibuster, that spending will likely end up accelerating EV adoption and other greening measures that reduce marginal oil demand. Here’s a snapshot of the Eurozone vs. the US and China in GDP terms relative to 2019 from Philipp Heimberger:

This likely understates the US case because many of the productivity gains taking place from working from home and more flexible work arrangements aren’t effectively captured by current GDP measures, whereas China’s recovery (as of now) is still dependent on increasing levels of debt financing inefficient investment. The pricing problem for Moscow is all the more apparent when you look at 2021 planned upstream investment levels among OPEC members:

Investment is down for low cost producers that could otherwise plan to lock in more market share without any substantial risk to prices in the medium-term. The idea that investment levels are wholly insufficient to meet future demand is being smashed by just how weak the demand recovery will actually be and rising likelihood that demand peaks well before the common 2028-2030 dates given by forecasts seeking a happy medium between bear and bull takes. In this context, it’s important to track the latest news from MinFin and Siluanov that as much as 1 trillion rubles ($13.57 billion) from the National Welfare Fund — now topped off by surplus oil revenues above the $43 a barrel price level set by the budget rule — will be spent on infrastructure projects for 2021-2023. It’s a relatively small sum given an additional 2 trillion rubles ($27.04 billion) in revenue are expected this year assuming current oil price levels and exchange rates. Regardless, one of the prime candidates to receive an infusion of investment support is Rosneft’s Vostok Oil. Rosneft has flatly denied its strategic planning includes any funding from the NWF, but it’s an open question given how unclear the economics of the project actually are.

The project’s moving ahead at pace regardless. On April 12, Rosneft and its Vostok Oil subsidiary are taking part in auctions in the Krasnoyarsk region for the right to use the Deryabinskiy and Turkovskiy fields per MinPrirody reports. Goldman Sachs has upgraded Rosneft’s equity valuation with a $10 target price for its GDRs with a recommendation to buy thanks to strong dividend growth. All told, the company’s got reason to feel more confident. But there’s an ongoing shift in its contracts and export priorities — not new, but accelerating — that speaks the fragility of the economic logic of Vostok Oil and the oil market. The new 2-year supply contract for the Polish refiner Orlen set the supply level at 3.6 million tons, down from the previous 2-year contract at 5.4-6.6 million tons. Poland’s long politicized gas imports in Europe, but oil’s a different matter since the market’s fungible. It’s not a source of real political controversy, but rather something to threaten canceling if other OPEC producers, for instance, offer discounts to compete with Russian crude supplies that have a built-in advantage due to the Druzhba pipeline. The supply cut, however, fits into a long-running trend of Rosneft cutting its own direct supply levels to European refiners and consumers and replacing them with contracted volumes via its trading arm and direct deals with the Libya’s National Oil Corporation as well as the Kurdish authorities in Erbil, Iraq. In effect, this cut signals they’re doubling down even more on Chinese demand and, to a lesser extent, placing volumes onto the Indian market via the port and refinery complex at Vadinar in Gujarat. But even OPEC’s short-term forecast hints at problems that were visible pre-COVID for Chinese demand:

The spike came from a supply-side surge in the Chinese economy, and annualized demand growth levels fell to around 500,000 bpd in 2018-2019 with signs of a further slowdown to come. As BOFIT notes, consumption was a net drag on growth last year in China and it’s important to remember that it’s recovered much more weakly than production in China with GDP last year boosted through property investment that did not generate significant wage or productivity gains in the economy. Rising Chinese exports reflect its inability to absorb rising production levels thus far:

Yet BOFIT and other forecasts show China returning to pre-COVID trend growth quickly, which is odd given that this trend has always been maintained via targeted debt expansion or supply side measures not reflecting healthy growth. Since consumption isn’t overshooting its pre-COVD trend, the implication is that end demand in China for things like oil, while still rising, won’t increase at trend either. It’s good Rosneft locked in those supply contracts in 4Q 2020 cause as of now, there’s little reason to view the Chinese market as an attractive justification for the scale of future production increases at Vostok, especially if peak demand is closer at hand now per IEA estimates. Topping all this off, Rosneft’s long game in Libya has been to await a resolution of the conflict — Moscow’s efforts backing Haftar backfired spectacularly — to secure upstream investment contracts since the financial terms are more attractive than in Russia and these projects secure a Russian economic and political presence for years and years to come. That’s in question with the demand picture changing and uncertainty over Libya’s effect on the global market for the rest of the year.

The fiscal system has adjusted to a lower oil price reality, if not to the reality of potentially falling demand. Russia’s oil sector hasn't, nor have its economists in positions of power been able to make much headway in generating a consensus about new vectors for sustainable growth. 2014-2016 triggered a change in Rosneft, which went from domestic consolidation of a commanding role in the oil sector to aggressive, debt-financed expansion abroad wherever possible to circumvent sanctions and find as many foreign stakeholders as possible to insulate it to whatever extent possible from further sanctions risks. This failed, most notably in the case of Venezuela, and it left the company only one option: grow through state largesse in the Arctic. But the pyramid scheme of subsidies and spending propping up Arctic activity has always relied on dependable demand and price levels for hydrocarbons. China held up the market from 2000-2020. With the close of that era, the significance of energy in Sino-Russian ties is bound to evolve to Rosneft and Russia’s loss. If I were a fly on the wall at meetings in MinEnergo and with Novak, I’d be warning them that whistling past the graveyard on the oil market didn’t turn out well the last time. Unlike today, Gorbachev’s economic team believed peak oil was a real possibility after years of demand decline from 1979-1984. They were wrong, of course, but at least they could envision things changing. The lack of imagination this go round speaks to the political hole the regime dug for itself as early as 2003-2005.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).