Top of the Pops

Tomorrow, the relevant ministers of OPEC+, including Aleksandr Novak post-promotion to deputy minister in the cabinet, will be meeting to discuss whether it’s worth gradually increasing output by 2 million barrels per day come January. From BoA’s Karen Kostanyan, there are still 200-300 million barrels of oil in excess of demand in storage around the globe and it could take another year to unwind that supply overhang. Factor in that OPEC+ is fighting weak demand and not US shale and the odds go up that the group hangs together to prioritize price over market share. However, this is where a lack of clarity on Biden’s likely policies — fostered by his own branding as a complete blank slate frequently in thrall of Washington careerists who artfully hide their own foreign policy preferences behind the language of human rights and liberal internationalism — is a problem for OPEC+. Take the EIA’s forecast about world liquids consumption in 2020 vs. 2021:

While I remain very skeptical of a significant change in US policy regarding Iran, additional volumes from Iran or Venezuela coming onto market due to a relaxation of sanctions would cover, to ballpark it, around 1 million barrels per day in short order of a nearly 6 million barrel per day demand increase against a larger net loss from 2019 and without sufficient evidence (yet) of US shale vanishing post-crisis. OPEC+ has only been able to do as good a job balancing the market because of its luck with US policy and production outages in Libya. Libyan output has recovered to about 1.25 million barrels per day — 75% of its per-2011 output — with the tentative peace prevailing between military factions on the ground, US sanctions took off hundreds of thousands of Iranian barrels of crude off the market, and Venezuela’s domestic woes took hundreds of thousands more off the market (then hammered by US sanctions). Washington is still playing a partial role of market manager, even if less directly and without any centralized control over its own production. I expect a cut continuation because OPEC+ has no other choice. Moscow’s faux enthusiasm shows they know the score on their end. But even with Moscow and Riyadh’s extensive cooperation, we shouldn’t rewrite the last 4 years of oil market history. Their success has been highly contingent.

What’s going on?

The program launched by the state to provide zero-rate loans to small and medium-sized businesses via 50 participating banks ends today. The MinEkonomiki claims that these credits — worth a lowly 102 billion rubles ($1.34 billion) — saved 1.2 million jobs and loans with rates capped at 2% saved another 5 million. But there are 70 million jobs around the country and many businesses aren’t even able to return to the money without interest due to the massive shock to domestic demand this year. It may be cheaper to procure credit now, but since the state has done nothing to sustain demand, providing interest-free loans still imposes a cost on business balance sheets. If the money were grants for business or else schemes whereby costs to keep people employed could be claimed out of the state’s coffers for at least year, it’d probably work better. Instead, Moscow’s claiming policy success while the country’s SMEs face a terrible 2021 where even at 2020’s policy-discounted average of 6.1% interest rates, loans will crush bottom lines if profits don’t return.

Industrial producers are losing short-term optimism for industrial recovery and growth per Rosstat. Much of this can be chalked up to seasonal factors though — December tends to slow things down heading into New Year’s and then Christmas in January:

Title: Index of Firms’ Certainty (seasonally-adjusted)Brown = extraction of natural resources Green = value-added production

Still, the recovery in outlook plateaued in 4Q with a great deal of lingering uncertainty about state support plans for oil & gas services and the state of consumer finances in 1-2Q next year since Russians appear to be borrowing less money as income deflation forces households to pay off debts and spend more thriftily. Net sales for Black Friday were down 39.2% year-on-year according to Sberbank, though online sales continue to show roaring year-on-year growth. Evidence of business stabilization in 3-4Q is still fragile. A lot hinges on the yet-to-be-agreed next OPEC+ oil production cut extension too.

Alexander Shokhin, head of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, has reportedly asked deputy minister Viktoria Abramchenko to lighten the requirements set forth by MinPrirody mandating industries reduce pollution levels. Putin’s May decrees from 2018 set out a target of halving Russian emissions by 2030. The trouble is what to use as the base year. At present, it’s 2017 and Shokhin wants 2019 to be used instead because of modernization efforts undertaken by the energy sector, thus lowering the overall reduction burden because of the phrasing of the mandate. On top of that, the current requirements don’t cover a bevy of associated emissions and sources of pollution. Vedomosti has relatively little insight here, but this fight is going to be pivotal for Russian industrial exporters if they want to keep pace with market developments and requirements in the EU and China.

The Federal Tax Service expects 116 new participants to join the 95 current members in using its electronic tax monitoring platform. The new joiners include SOEs like Rosneft and MNC subsidiaries for firms like Procter & Gamble. By building out a shared platform whereby tax data is collected, stored, and transparent, the FNS is reducing the amount of paperwork needed and, in theory, making it easier for businesses to operate, understand, and contest their tax burdens. The problem, however, is that the improvement of tax administration is really an initiative aimed at increasing receipts and the state’s ability to monitor business activity. That’s not to say it’s malicious or a corrupt initiative — far from it! — but rather that it’s an area where administrative reform, while successful, is not going to fix structural challenges. The current initiative might encourage more foreign firms to operate in Russia, though, and that counts for something.

COVID Status Report

The last 24 hours saw over 26,000 new cases and continued growth at levels dangerous for public health and the economy. Data as of Nov. 30 pegged the week-on-week growth rate at 10.1%, an increase from the previous week’s 7.9% rate:

There is, however, a mini-trend that’s a glimmer of good news if it holds. The last 4-5 days, the infection rate in Russia outside of Moscow has plateaued. My money’s still not buying the good news yet, though. The fact that Rosstat data shows a death toll 2-3 times higher than the numbers put out by the Operational Staff — cited for that graphic — suggest that even with improved testing capacity, things are probably a little worse than it looks (though nothing like the gap between data collection and reported numbers in April-June). In absolute terms, an estimated 510,000 people are under medical observation with COVID-19 in Russia right now, a little above .03% of the population. If the R is at or above 1, no one’s out of the woods yet. The EpiVacCorona vaccine is being reviewed for its public rollout by December 7-8 at MinZdrav, so it’s clear that there’s some light at the end of the tunnel for their plan to stumble along till they could start vaccinating people. If the growth rate week-on-week hangs around or above 10% through December, however, the medical strain and business uncertainty are going to be unbearable. It’s good that universities in SPB and Moscow are going remote for the next few months. Should help flatten the curve headed into the New Year by reducing transmissions to students’ families and friends.

Corps Bride

Russian corporations are getting slammed by the pricing losses for some exports, weaker external demand, and weakened domestic demand this year. BNE intellinews’ snapshot captures the story well stacking up cumulative profits for 2020 vs. the past 4 years. Cumulative profits for Jan.-Sept. stood at just $91.7 billion vs. $153.8 billion for 2019:

Profits are a flow, converted into a stock. They’re accumulated out of the differential between revenues and costs. Zooming out, those figures say a lot about the available resources needed to invest in the Russian economy. Presumably profits, both realized today and forecast into the future, form the base upon which corporations grow. Revenues are in practice more relevant for some corporate examples — take giants like Amazon and systemic underpayment of tax receipts by generating losses — but suffice to say that corporate profits at the national level provide a pool of excess money to be invested into new production, into long-term interest-generating instruments, acquire fixed assets like property, licenses to extract resources, etc. Doing a little ad hoc adjusting, that means that this specific pool of resources was equivalent to about 5.5% of Russia’s GDP. Last September, that figure was more like 9%. Here’s why that’s a serious structural problem for the Russian economy, its financial and fiscal health, and its ability to generate growth using domestic demand and domestic resources going forward.

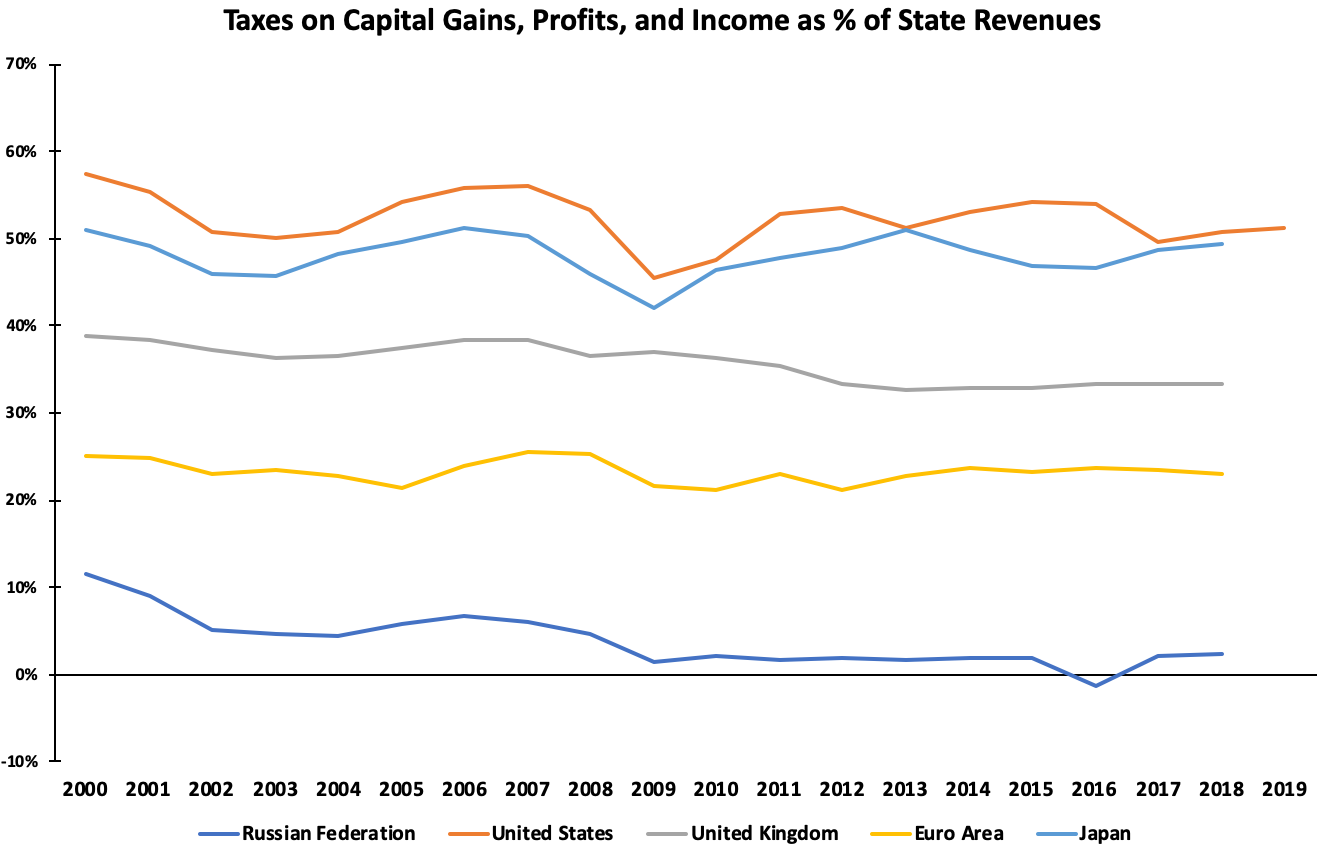

On its face, the 2019 numbers are healthy. After all, US corporate profits as % of GDP in 2019 was 10.4%, suggesting that last year — a relative “return to normalcy” for Russia post-2014 — was a strong one for Russia Inc. But in actual macro terms, the picture looks a lot worse. This is World Bank data so it’s not perfectly precise, just easy to pull quickly. If you look at taxes on capital gains, profits, and incomes as a % of state revenue, the problem becomes a bit clearer, even if corporate profit taxes aren’t broken out:

If we think of tax revenues as a redistributive mechanism to raise capital, reduce inequalities, and finance either investments or else programs and spending that the market is ill-suited, that requires longer time horizons than most investors are comfortable with, or else can allocate resources in a more efficient manner than private sector participants scrambling to create rents for themselves, then Russia’s lack of direct taxation on capital gains, profits, and income as a major revenue source suggests that its profit figures are artificially high. In other words, Russia should be using its presumed oil rents to create more financial space for corporate investment into non-oil & gas sectors to aid the slow and inevitable rebalancing of Russia’s fiscal system over time. But Russia’s saddled corporations with a variety of social expenses and even with a low nominal tax rate on profits, Russian corporates actually pay a higher contribution and tax rate as a % of profits than in virtually all developed economies except Japan. I included Saudi Arabia here because there was data through 2019 and it’s a more “pure” case of oil rentierism:

You can see how the Trump tax reform in 2018 saves US corporates yet more cash… anyway, despite profit taxes playing a (relatively) negligible role for federal revenues — as a caveat, it’s unclear if the underlying data is only looking at federal revenues since corporate taxes are assessed regionally in Russia and the % figure does seem a little low, though by no means totally off-base — Russian corporates are on the hook for a similar tax and contribution rate out of their profits as Japanese firms. What this really suggests is that profits are, in many instances, depressed by the inherited infrastructure of formal and informal price controls, agreements, and pressure from Moscow. At the same time they’re depressed, the actual effective tax burden on profits is not that onerous and in line with the lower end of rates abroad and, given the space to capture rents through policy interventions, market protections, and direct and indirect subsidies such as depressed energy input costs, you’d expect that corporate profits would either be higher or that the rate of investment activity across the Russian economy driven by the accumulation of profits would be stronger. Basically, Russian corporates — even those with healthy balance sheets and strong showings for things like online retail or banking services — are operating on a market that is suppressing their ability to earn. This generates deflation, lower net profits, depresses wage and output growth, and also increases the salience of state spending and procurement to drive economic activity. It’s damning that this September was the first time Russia spent more on the economy than defense out of its budget allocations since 2014.

Looking to Rosstat for turnover at the corporate level for Jan.-Sept. starting in 2010 and adjusting it per the end of year exchange rate and comparing it to the average annual price for Brent, a clear pattern emerges for Russia Inc.’s net turnover:

The oil price is the business cycle in some respects, except as we can see post-2014, the 2018-2019 rise didn’t actually trigger a large increase in 2019 in exchange rate adjusted terms against the USD, partially because of reserve diversification into gold, the Euro, and CNY. Now, to be clear, this makes logical sense since the exchange rate tracks with the oil price, but it’s important because of the presumed potential for healthy corporate profits in sectors that benefit from protections against import competition as well as the continued role of imported goods and services for large segments of Russia’s corporate world. Accounting for the currency devaluation in constant terms, Russian corporates are probably a bit below where they were 10 years ago on net (exchange rates were in the 30-32 band against the US$ in 2010-2013) without much economic growth since 2013 and are now facing what will likely be an increasingly harsh tax environment as the current round of fiscal consolidation will have to soak not only the extractive sector, but keep improving tax receipts from other companies and sectors. Assessing corporate profits only in ruble terms slightly misstates the picture given exposure to eurobonds and foreign-denominated liabilities, but is fair given that these companies have had to focus on the domestic market since 2014 anyway. The fiscal system and business environment in Russia, now lacking stimulus from the state, promotes chronic underinvestment into capacity. If corporate profits retained hit 10% of GDP given the relative burden on businesses and restraints capping their profitability, including the lack of income support during the current crisis, it’s very difficult to see administrative improvements of a system structurally suppressing supply and demand in different ways leading to significantly improved growth.

The impetus for corporations to invest into productive capacity are undermined anytime policy measures crimp potential profits. Some of those constraints are perfectly healthy. You don’t want raw sewage being poured into a river next to a city or someone making a killing selling defective equipment. But regulatory intrusion and fiscal systems in Russia often create rents or perverse incentives. In the case of the oil & gas sector, the highly progressive tax code dovetails with a lack of state support for exploration activities making the development of newer oil & gas fields highly risky and expensive. That has a net knock-on effect for service providers, whose demand for legal and financial services filters into regional capitals and Moscow and so on. If you’re in logistics, you’re able to still profit considerably but you’re going to be dealing with the often arbitrary nature of fights over tariff rates on the rail network — monopolized by the state — vs. the trucking sector, which has to contend with not only the Platon tolling system but the need to rationalize domestic fuel prices over time to make the country’s refineries more profitable and efficient under the evolving oil sector tax regime since it raises feedstock costs. These types of policy interventions may only marginally alter costs of inputs and the prospective profit margins from outputs, but there are loads of industries with tight margins or else industries that derive less benefit from investing into higher efficiency, cost-cutting, and new production because of marginal losses.

Zooming out, you can see how the construction of the pre-COVID fiscal and economic settlement in Russia revolved around the 2000s commodity boom and how the growth of Russia’s consumer economy was driven by external demand:

Since 2008, Russia’s lost massive ground to China in relative terms because of the slow, if inefficient and structurally unsound rise of China’s domestic demand. It’s lost ground since 2012-2013 to the US, even lost ground to the Eurozone despite its massive dysfunctions. Since 2013-2014, it’s lost bigly to India and only managed to keep pace with Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole despite having what would appear to be a more complex economy with a bit more fiscal capacity in most cases to sustain domestic demand and growth. Corporations are only going to realize the productivity gains that Glazyev et al want to see if they have better incentives to invest and a more stable business environment. The latter requires consumers whose spending power isn’t declining in real terms every year. Both require more than administrative adjustments the likes of which Putin has tasked PM Mishustin with pushing through.

What’s odd is that Russia exhibits the same levels of gross fixed capital formation as % of GDP as developed economies in the Eurozone and US (slightly lower than Japan) but obviously lags behind China massively where systematic over investment into unneeded capacity generates massive figures. Russia’s hanging around 21% of GDP once it settled post-2014, in line with the US and Euro Area. But given how much higher inflation in Russia is (ironically due to underinvestment in new capacity, weakened price signals creating temporary or seasonal shortages, and infrastructure), the depreciation of existing assets is more harmful to corporate balance sheets than their western peers living on home markets with inflation regularly in the 1-1.5% range instead of 4%+. Corporations have less reason to risk long capital in a higher-inflation environment if marginal returns are weakened via price interventions and state-generated rents, creating this endless ouroboros problem in the Russian economy. The only way to break through, it seems, is to accelerate the shift away from its oil-dependent fiscal regime to target profits and capital gains for revenues while also risking higher short-run inflation by lifting some price and tariff control measures. No matter how healthy Russian corporates’ balance sheets might look from afar, up close things aren’t rosy. It’s not a zombie firm epidemic to worry about, but a zombie economy.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).