Top of the Pops

A tanker’s gotten stuck in the Suez Canal, leading to speculation about the impact on energy markets since large volumes of crude oil and oil products flow through the canal. Crude oil won’t be much affected — there’s pipeline capacity bypassing Suez in Egypt as well as in Israel if need be. Products, however, are a different story and we’d expect to see some very short-term disruptions and shifts as importers hunt for new suppliers or swap orders depending on where tankers are currently located. It’ll be cleared up within a day or two, though. The effect is unlikely to do anything to the downward trend for oil prices since the oil market has realized for the millionth time that demand isn’t out of the woods yet due to the potential for continued waves in Europe and emerging markets where vaccine rollouts are lagging. The most immediate short-run impacts will be felt in Lebanon — now experiencing an economic meltdown due to currency crisis — and Syria, where Israeli strikes continue to quietly escalate the conflict by risking greater retaliation. The bigger market problem for any price upside in the months ahead, as usual, lies primarily in the oilfields of Texas. Even though Wall Street’s more skeptical than ever of returns on shale drillers, the flood of liquidity hitting the US banking system from the Treasury General Account and Federal Reserve’s continued commitment to easing have pushed down the cost of refinancing existing debts to seven-year lows:

In the first 10 weeks of 2021, US shale drillers sold $11 billion worth of debt. That’s over $1 billion a week propping up drillers just waiting for OPEC+ to kick the price up a little bit more. Canadian firms are also getting in on the action. The current downward trend for prices will have a far more muted effect on US production for H2 if these rates hold for long enough (note that junk yields are rising a bit in response to inflation expectations, but they’re still a small relative adjustment). The moral of the story is that since the cost of capital is an essential factor for determining the hurdle rate of return for any investment in an extractive industry like oil, Russia and Saudi Arabia can’t kill shale so long as shale has friends in high financial places, namely the Federal Reserve and, in this case, the US Treasury.

What’s going on?

‘Insomar’ polling shows that as of now, turnout for the September elections is expected to hit 55%. That’s a little low if United Russia hopes to sweep back in with a safe supermajority, with lower turnouts tending to benefit the opposition, systemic or otherwise, since they lack the same level of command over administrative resources as United Russia in many contexts. Only 42% confirmed it as a hard yes, with 13% saying they’d more or less participate. 12% won’t participate and 31% are undecided and waiting to make a decision closer to the elections. That’s a huge block of ‘swing’ voters without too much to guide us as to what would drive them to the polls — would they go to reward parties for efforts helping them etc., vote for a future change, or prefer to stay home since it’s all rotten anyway? Only 33% are for UR, though 54% say they’d vote for them on a party list basis. The Fund for the Development of Civil Society estimates final turnout will hover around 45-48%. Others expect it to be above 50% because of the organizing activity of the non-systemic opposition, which boycotted the 2016 Duma elections. My guess is that people are waiting to see how the recovery pans out. Even with Navalny in prison and much of his staff and team targeted and harassed, the opposition will have a lot more to work with until the Kremlin announces that social spending package. The fact that it’s vanished from public discourse suggests to me that either it’s truly been killed by internal blocs opting for repression, or perhaps more likely, being kept under wraps so it can be a bigger surprise and buy more coverage for longer.

AKRA data shows that regional governments’ borrowing is up year-on-year with a few regions borrowing when they normally wouldn’t (here’s looking at you, Yamal-Nenets!). All told, 29 regions issued debt as of February 1 vs. 28 regions the same time last year. Issuances outside of Moscow totaled 406 billion rubles ($5.35 billion) whereas they were 282 billion rubles ($3.71 billion) in Moscow alone. The following shows the top 10 regions by planned issuances (as of now) for 2021 in blns rubles:

Kommersant’s writeup notes that most of the borrowing has been via short-term maturities of 6 months to 2 years. They’re hoping that the recovery powers the budgets through as will any additional support measures such that with the rates lower now than they were a few years ago, they can afford the increased debt load. But it’s a big risk and likelier to worsen regional credit ratings given the state of the recovery and tax receipts from businesses. There’s also the over-concentration of systemic default risks from municipal debt to consider — Sberbank has been the counterparty for 85% of the issuances. Either a greater degree of fiscal devolution or a higher level of federal support are needed to prevent this from becoming a problem in the near future.

MinFin backed off a further OFZ issuance citing market volatility for the ruble and non-resident flight from OFZ purchases in the wake of “Putin is a killer gate.” Citing rhetoric and sanctions risks from the US explains some of the psychological jumpiness, but not the context for returns. The fact is that rising inflation expectations in the US reflect a stronger growth path ahead, which is pushing US bond yields higher, makes the American economy a better bet for equities (since inflation is still likelier to be on the lower side of 2-4% with a boom), and reduces the attraction of emerging markets for yield. In other words, Russia’s volatility fits into a broader emerging market story that reflects the differential effects of US stimulus, Europe’s struggles, and rising commodity prices. However, some market participants are convinced that the rising short-term rates reflect insider information of the Biden administration’s intentions to levy sanctions on Russian sovereign debt, which would trigger a direct capital outflow of $8.5 billion followed by billions from other investors put off by US pressure. Sber and VTB have publicly commented that they’re willing to cover all of MinFin’s issuance requirements if need be due to sanctions, so I don’t think the issue is the state’s balance sheet. It’s the political uncertainty. The ruble has bounced back from its lows, though OFZs are still wobbling. My own sense is that it’s likelier that Russians’ assets in the US would be seized than debt targeted for the obvious reason that it would hurt millions of innocent people in a manner far beyond anything the current sanctions regime has done.

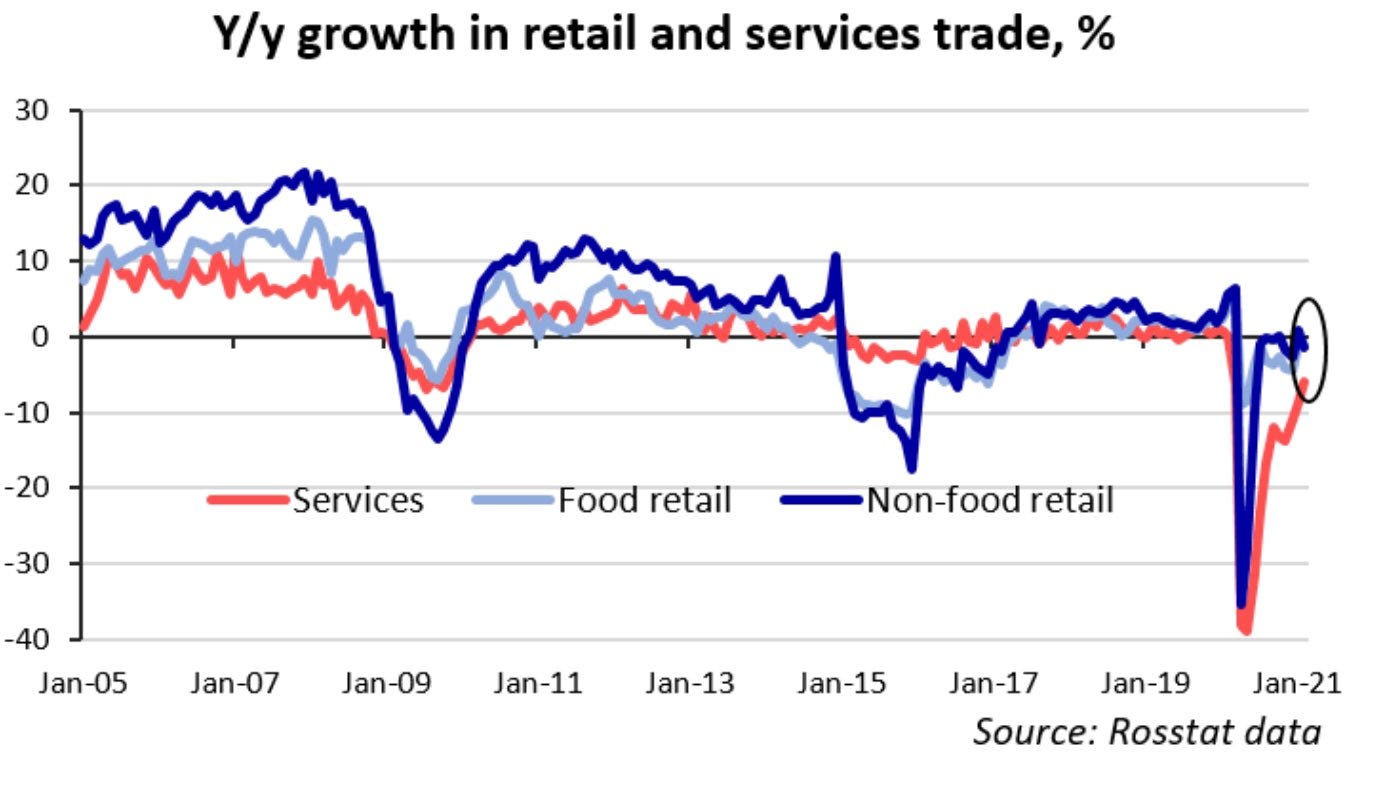

As of February, the volume of debt payments overdue by at least 90 days in Russia had grown 18% year-on-year and 1.3% vs. January, reaching 149.6 billion rubles ($1.97 billion). Overdue debts accounted for 15.6% of all consumer credit, an increase from 14.2% last year. The tick upwards in the data accompanies signs that services demand is finally recovering compared to food and non-food retail as restrictions end despite the persistent threat of a new COVID wave:

Considering that delinquency on payments is rising based on the 90-days late metric, we know that real incomes fell once again last year, and the growth path for services demand since 2015, the services recovery is not going to have a significant impact on growth. Services inflation has trailed other inflation metrics by so much because Russians have gotten poorer since 2013. A return to the prior path is only possible if debt is financing that additional consumption above prior years given income decline over the previous time period. Further, it’s not estimated that the mortgage portfolio held by Russian banks — expected to be 10.6-10.75 trillion rubles ($139.8-141.8 billion) — will surpass the volume of consumer credit banks are providing. In other words, housing prices are likely going to have a greater effect on spending expectations in the year(s) ahead given the changing composition of demand. People may not consume as much in the way of services and may prefer to save up to buy a house or apartment to have their own space and a store of wealth for themselves and their families. Alternately, they simply won’t be able to afford either. A related problem is that as the key rate hike filters into borrowing costs and deposit rates, companies are expected to cut as much as half of their borrowing and may well just park their money in banks to collect interest until they deem the environment healthy enough to invest. The obvious result is less private sector spending that becomes household income. If the 90-day delinquencies continue to rise, then the recovery is probably much weaker than topline data suggests.

COVID Status Report

8,861 new cases reported alongside 401 deaths per the Operational Staff. Putin finally got a vaccine dose but no one saw it, so we’re left asking questions like whether or not a mime’s death in the woods at the hands of a falling tree happened if no one was there to witness it? Things keep moving towards a full national re-opening, despite the risks. Domodedovo airport in Moscow has begun issuing vaccination certificates to travelers in English in preparation for more international arrivals. Belarus has secured supplies of Sputnik-V at the same rates as the African Union — about $10 a dose. According to Tatiana Golikova, there are about 6,000 vaccination points across the country. You’d think the take-up would reflect that but:

Russia’s right around the world average from the data available and in pace with China, which is as likely to speak poorly of its production capacity as it is the population’s trust in the vaccine. These figures are still far too low to meaningfully affect infection figures if there’s a resurgence in April thanks to the end of restrictions. You’d hate to see vaccine exports rising because of a lack of domestic consumption…

Whose model is it anyway?

I was trawling for something to write up since it’s been a slow morning, but I finally chanced upon a rather odd piece from Lenta that raises serious questions about the competence of the effort Mishustin is reportedly leading to find a new ‘development model’ — how Russia loves its models — for the economy and social sphere. According to Lenta (with a grain of salt taken), the government’s internal discussion is trying to use South Korea as a reference point, citing its use of massive conglomerate chaebols and its leading families to command the heights of the economy and drive its development. Moscow wants to salvage comparisons to the “Asian tiger” economies that generally rose through a mix of aggressive state protection and aid with the willingness to expose exporting firms to serious competition and failure as well as the suppression of domestic consumption by pushing the population to save in excess quantities and then funnel that money via the banking system to lend to industry at lower rates. South Korea specifically is an interesting choice of model since political scientists have long noted Russia and South Korea offer oddly divergent paths despite institutional similarities — wealth and economic power in Russia have historically been concentrated at levels similar to that in South Korea, yet South Korea managed to transition to being a democratic state. South Korea has historically been somewhat of a riddle for economists, political economists, and political scientists as its growth path doesn't neatly correspond with other examples, yet it managed to join the OECD. The unique pressure of its own business elites and the United States government to reduce the state’s intervention in the economy while giving it easier access to the US market because of the country’s geopolitical importance played a significant role.

Unlike Russia, it’s process of policy-led industrialization took it from being a net importer to a reliable net exporter by the mid-80s and early 90s whereas Russia’s current account surplus since the Soviet period has generally reflected the suppression of consumption in various ways. The Four Asian Tigers — South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore — all run large surpluses via industrial exports rather than resource exports (HK is the odd duckling since it’s a finance hub for mainland China and its own current/capital/financial accounts are recycled into China’s). I’ve included mainland China and Japan for reference and note that Taiwan is excluded from World Bank data. South Korea’s current account also fluctuates more than the others from deficit to surplus:

Russia runs similar levels of current account surplus as Japan, higher than China now (though the COVID stimulus changes this look a bit), and used to run much higher surpluses than South Korea when oil was riding high. We can see the surplus for Russia decline first as oil windfalls filtered into consumption and imports and then post-2013, oil price declines alongside consumption stagnation and falling incomes. What’s odd to consider here is that if Russia is serious about mimicking the structure of the South Korean economy, not just slapping some paint on branding because chaebols are reminiscent of existing SOE and parastatal market and wealth concentration, then they want to swap the resource-based trade surplus with consumer goods components or similar value-added production for export. German Gref’s been intimately involved in the internal discussion, which helps explain why the government program resorted to a laundry list of English-language consulting-esque jargon when the initial details of a plan in the works were leaked. There are only two ways Russia can reasonably finance this shift: investing its existing export earnings into new productive capacity — much harder with a lower overall oil price environment — or debt-financed, state-led investment that faces serious corruption and capacity limitations. But that’s not what the new proposal is really about. Even Lenta’s coverage acknowledges that the government is not consulting any independent experts/expertise in devising its proposals, locking out real critics and limiting the policy circle to the players in the system who have no incentive to push hard for systemic overhauls.

The biggest gap using South Korea as a model is that after the May 16 coup in 1961 when Park Chung-hee came to power with his Revolutionary Military Committee, the state began to ruthlessly apply export discipline — exporting firms that received aid via state subsidies, protections, or else subsidized credits from the banking sector awash with household savings and consequently underperformed were culled. The country’s leap up the development ladder happened as a result of its judicious use of state industrial policy coupled with the willingness to let ventures fail when they proved unable to compete. This latter dynamic has never existed under Putin since the state has maintained several decades worth of industrial policy that prefers to maintain employment over efficiency and export competitiveness for electoral gain. Comparisons to a South Korean model are irrelevant unless the state intends to let big firms fail, unthinkable for now. The other obvious distinction is that South Korea has no comparable fiscal and macroeconomic economic base built off of resource wealth and exports. The political competition for resources between sectors and lobbies in South Korea differs strongly in this regard, particularly since tax receipts that matter most for the budget have to be derived primarily from corporate profits and not a variety of taxes on extraction and export. The political incentive structure for tax and fiscal policy is far different. The following data is a bit out of data — the graphic is from 2018 — but it similarly captures what Russia’s not doing and doesn’t seem capable of doing well based on its current institutions:

Increasing spending on R&D has been critical for South Korea to maintain its relative edge. Another aspect of the ‘model’ for the government that’s odd to contemplate is that the exporters of Asia, broadly speaking, rely heavily on US consumption i.e. its trade deficits and now on Chinese consumer demand to maintain their surpluses. This also ties into the region’s responses to the 1997 financial crisis that hit currency exchange rates hard for many regional economies, promoting a greater degree of conservatism, impetus to hold more reserves (and therefore suppress consumption to support current account surpluses), and strongly aligning the region’s net exports with US economic policy. This from an old Brad Setser thread is a useful reminder:

The US stimulus in 2020 helped push it back up and allowed regional economies dependent on trade surpluses to weather COVID much better. If Russia were somehow able to shift its export basket towards industrial output, it’d either do little to or even strengthen its relative dependence on US and now Chinese fiscal and monetary policies since they drive the global consumer economy (or else the safe assets underpinning global trade) and consumer goods, electronics, more are still going to be bought in huge quantities as economies become greener, and emerging markets now consuming more oil have a long way to go as goods consumers. China’s current account would become the most important thing to watch, yet last year, China’s exports into Russia overtook imports for a spell because of the industrial asymmetry in the relationship and Russia’s weak existing industrial policy. Russian economist Dmitry Nekrasov is convinced that there is no risk of a true economic crisis tending towards collapse in Russia unless oil prices were stuck at $20 a barrel for 7-8 years. His view is probably close to the consensus view in Moscow — oil has them trapped economically, but also permanently cushioned by dint of the budget rule, existing oil sector tax code, and relatively weak effect that price levels have on investment into production in Russia (only below $30 a barrel does it really become a huge problem). To my mind, it’s an absurd stance to take since oil at $20 a barrel would wreck industrial orders across the economy, with deficit spending being the only off-setting mechanism available. This all makes the South Korea leak all the more beguiling since it never developed out fo this mindset and context.

Interestingly, the hunt for a new economic model isn’t just a matter of regime politicking and a chance for Mishustin to shine. Even systemic party A Just Russia has called for a new economic model, though in their case they’re criticizing the construction of capitalism in Russia and saying people want something fairer. It’s the view of outlets like Krasnaya Vesna that the real problem lies in the fact that the economic bloc, the supposed liberal reformers, have actually stuck the country deeper on the ‘oil needle’ and its resource dependence because of their conservatism. I tend to agree with this view, though I can’t say I endorse Krasnaya Vesna. The EAEU as a bloc is cognizant that stagnation awaits it without change. That’s why you’ve seen more movement from Kazakhstan to create more joint venture opportunities using sovereign wealth with Russia. There is no substantively new model being developed by Mishustin, Gref, or anyone benefiting from the current system. The first political force to truly propose one, even one out of power, might surprise if the public reacts positively.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).