Top of the Pops

I checked Levada’s homepage briefly this morning and came across their latest poll result. It challenges the suppositions made by many in the West about how life in Russia is experienced by most Russians and also points to a growing political problem beneath the surface:

Title: Do you feel you live as a free person in our society?

Red = definite yes + overall yes Blue = definitely not + overall no Grey = hard to say

Despite the creeping escalation of repressive measures over the last 8 years, more people feel like they’re free. At the same time, we see polarization taking place. People who used to be on the fence per this poll drifted into the “no” camp and there’s been more than a 10% gain in “no” respondents since 2014. Now the “yes” category is coming down, which could also be some people’s reaction to COVID and related public measures, but I suspect has far more to do with how explicit political repression has become. Yet we still see fewer people saying “no” today per this poll than before Crimea. Does that matter for September? I suspect the qualitative significance of the question has evolved, aided as well by the net reduction in the prison population over time. But 40-42% of people saying they don’t feel free living in a system that was still politically competitive, if not necessarily per completely democratic norms, from 2000-2011 is far different from a figure now climbing back towards 40% with Putin effectively given the option of staying around as long as he wants as the state has replaced anyone competent in the bureaucracy with political technologists. I also suspect freedom means a lot less to someone when it feels like the freedom to starve. According to VTsIOM, 54% of Russians support higher taxes on them to provide support for the poor. That’s not necessarily good news for United Russia — systemic parties can seize on these issues too — but something else to consider about campaign planks and the economic consequences of reducing household spending power further.

What’s going on?

Today, Novatek and Severstal signed an agreement to jointly launch a hydrogen project in Cherepovtse in Vologda oblast’ by 2023. This and next year, preparatory works laying out plans for relevant infrastructure will take place as well as the financial model monetizing any production — that bit’s going to be quite tricky. There isn’t a strong market with lots of pricing schema and contracts as reference points despite knowledge of production costs, which makes it harder to estimate margins and so on. Clearly Anatoly Chubais’ assertion that hydrogen is the thing that’ll save Russia’s status as an energy superpower — I’d argue it ceased to be one by 2015-2016 — is getting through to firms and billionaires in search of new rents. Novatek and Severstal are hoping to deploy green technologies to make sure it’s “blue hydrogen,” and therefore low to zero emissions and recycling CO2 and methane for production. According to Fitch, the project will cost in the range of $100-200 million assuming no major price inflation. The aim is to get hydrogen down to $1.50 per kg, at which point it could competitively replace coal. Right not that figure is closer to $5-7/kg. There’s another reason Russian firms need to get these projects going. It gives partners like BP, perhaps Total at some point, German industrial firms, and others a reason to partner and invest since there’s no conceivable reason the US and EU would try to directly attack green investments via sanctions.

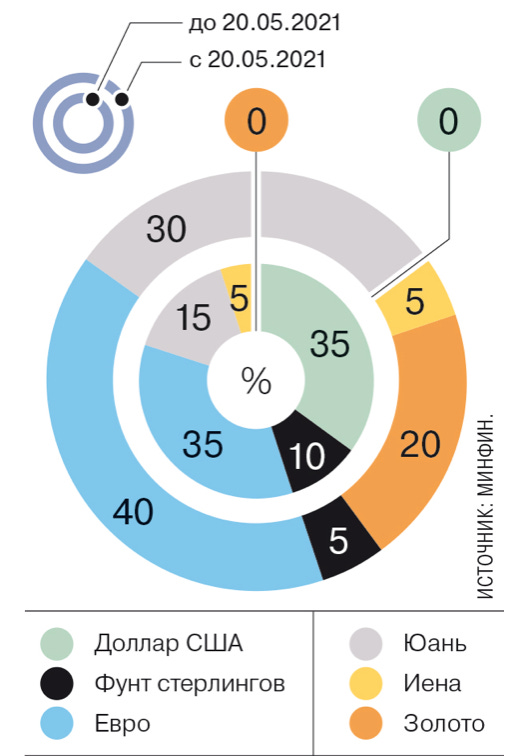

Kommersant had a useful graphic showing the planned change in the National Welfare Fund’s holdings per the decision to completely de-dollarize its holdings. The inner circle is before and outer after the decision:

Green = USD Light Blue = Our Grey = Yuan Black = GBP Yellow = Yen Orange = Gold

As finanz.ru terms it, MinFin and the Central Bank are carrying out “operation de-dollarization” — useful because it highlights how completely political and illogical it is economically. As Yakov Feygin noted, the move just increases transaction costs for Russia in self-inflicted fashion. Sanctions risks clearly motivated the decision, though it beggars belief the US would ever cut off Moscow from SWIFT since it was only able to levy that level of punishment on Iran with a multilateral coalition of states, including Russia and China, supporting the move. The siege mentality is real and somewhat understandable. I wouldn’t trust the US congress to craft smart sanctions with a clear strategic target and intent in mind. But this is just the latest weird turn, stupider still since gold is priced in USD and provides a relatively illiquid type of reserve i.e. you have to sell it for currency, and that currency is almost certainly going to be US dollars. Just an unnecessary transaction cost with no real material benefit dodging the dollar unless China wants to risk more of its export sector and financial instability truly internationalizing its currency.

One of the interesting lines of thought to emerge from SPIEF has been the shared belief that globally, state involvement in the economy will expand, not just in Russia. As expected, figures like German Gref and Maxim Oreshkin link that to ballooning deficits and excessive state expenditures that aren’t sustainable. They’re probably wrong for the simple reason that public-facing Russian economists and corporate leaders refuse to consider the possibility that there’s been a chronic shortfall of demand among developed economies, most egregiously from Germany and within the Eurozone but also from the United States’ comparative refusal to expand social spending and the widespread suppression of labor’s bargaining power. Russia’s national strategy documents and economic outlook shoehorn these types of developments into their understanding of multipolarity, and one can imagine the unimaginative minds of the security bloc(s) in Moscow somehow seeing this outcome as an affirmation of their belief that the state must have a deciding role in economic matters. But the energy transition is ultimately a global crisis of central planning — failures of industrial and energy policy are transnational problems rooted in the policy preferences of western donor classes, American bankers, German and Chinese manufacturers, and so on. The hollowing of state capacity in the US in particular has added a number of complications to the geopolitical components of energy transition, including China’s dominance over solar power supply chains. The worst possible thing economically for Russian firms reliant on state help or else driven by Russian state interests and policies are more active government intervention on western markets with governments more willing to securitize investment relationships, more able to foster competition using their fiscal powers to ease budget constraints on firms, better able to commercialize R&D, and better positioned to utilize and improve human capital. The more the climate crisis defines OECD politics and policy approaches to the economy, the more important the power of the state. It’s a direct challenge to the traditional conceptions of ‘hard’ power and state power one can infer from how figures in Moscow talk about international politics, and something worth considering as green deals take shape.

RZhD is looking for funds to cover infrastructure investments needed to provide adequate carrying capacity from Elginsky and other coal fields in Yakutia by charging an “investment tariff” on shippers carrying coal to Far East ports. These funds, therefore, will support efforts to continue modernizing and expanding capacity on the Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) without an increase in federal spending, backed as well by some money from the National Welfare Fund meant to cover 25% of financing needs. Elginsky is a flagship project indicative of the operating assumptions of the government in Moscow chided by the IMF at SPIEF for not taking the energy transition seriously enough. Elginsky is expected to produce 40-50 million tons of coal annually in the coming years making it the world’s largest single field. At present, RZhD has no real plan. They haven’t even decided whether to electrify the track or not or else which ports to send supplies from Elginsky and other fields to in the end. Shippers have to consider these proposals as well and come back with a counter-offer on what they think is a reasonable rate. Part of me wonders whether this would end up being an excuse to mandate the deployment of hydrogen-powered trains, but that’s probably a ways off until more production in Russia is actually built up. The episode is yet another example of the (un)intended consequences of the regime’s approach to fiscal policy. By forcing operators to pick up more of the costs, admittedly softened using the NWF, they’re effectively transferring the financial to firms and comfortable reducing their profits without actually raising direct taxes on them. It makes sense for infrastructure in general. Charging users can be effective, if risky since asset owners can also just collect rents in the end. But Moscow is asking shippers to foot the bill for an export that eats up an insane amount of physical shipping capacity at the risk of a near-term shift on external demand that lowers margins.

COVID Status Report

The Operational Staff recorded 8,947 new cases and 339 deaths for the last 24 hours. To give you an idea of the gap between the messaging and official data from concerns among hospitals, there was actually a hospital in the Moscow burbs that has opted to refuse to treat patients who haven’t been fully vaccinated and back on May 25, the Moscow oblast’ authorities apparently told hospitals to vaccinate all patients being treated or else sent to sanatoriums. Basically, if they can’t get you to do it on your own and you end up in hospital, they figure they’ll try to vaccinate you there if feasible. Mikhail Murashko used SPIEF to note that COVID wasn’t going anywhere if Russia only achieved vaccination levels of 30-40% of the population, citing the possibility of requiring as high as 90% vaccination rates to achieve adequate collective immunity. It appears the Ministry of Health is internally discussing what they can politically announce without annoying the bosses, as it were. Anna Popova from Rospotrebnadzor is asking people not to listen to COVID truthers. The fact that a weird amount of energy Kirill Dmitriev put into criticizing western pharmaceuticals’ spin machine rather than the poor take-up of the vaccine in Russia proper where Russians openly don’t want western vaccines suggests that after Putin shot down the idea of mandatory vaccinations, everyone’s out of ideas and clinging to the positive PR from late last year if they can manage it. At least Putin wants to vaccinate migrant laborers now and vaccine tourists.

Crying for help

Anastasia Tatulova, speaking in her capacity as ombudsman for SMEs, had some choice words at SPIEF about the state and political environment:

“Businesses in any industry need all of two things to grow rapidly — efficiency and security. Nowhere, not in a single slogan at the present moment, not in a single regular strategy, are these words [mentioned]. Anything else is there — digitalization, acceleration, generation, sandbox. Only these two words are missing.”

Tatulova’s speech at the plenary session similarly noted that more economic activity is drifting into the shadow economy. The constant assurances that the economy is recovering and everything’s alright, per her account, reflect the insulated world of Moscow bureaucrats fat off of their posts and beholden to groupthink. She’s of course correct. Behind the facade of effective stimulus responses lies a different reality facing the business owners and businesses making sense of the national COVID response — the municipal waste reform handing out contracts to friends has increased the takeaway cost for garbage collection as much as 500%, the cost of registering additional lease agreements with Rosreestr skyrocketed 22 times since COVID began, fine collections have tripled in the last three years (though the COVID moratorium helped some), and the reduction in insurance premiums paid by businesses since last April-May has only applied to employees who’re earning more than most SMEs often pay. In short, the state screwed the sector and fostered the narrative that it had successfully handled COVID because during the early phases of the new commodity price cycle, Russian exporters benefited. But that eventually fed back into higher inflation levels domestically by the end of 3Q 2020. As she summed it up:

“We have a total crisis of confidence [between] the authorities and business, and many problems stem from it. You spit on us, you patronizingly talking with us like with the needy, saying we know what you need. And we hate you. And this is bad for everyone.”

We can focus on the bigger international stories where large corporates make investment decisions, draw interest and scrutiny from investment banks and commodities markets, and the like. She went off at length on the illogic of the state’s tax system as well and refusal to incentivize investment effectively because of the arbitrary imposition of taxes and constant changes. But here, it’s exceedingly obvious that the recovery we’re supposed to be seeing now is not being felt by SMEs at all. They’ve been left on an island. Even big businesses are worried about the arbitrary imposition of new taxes, regulations, trade limits or bans, and so on. German Gref explicitly came out against Andrei Belousov’s accusation that businesses were ‘screwing’ the state and failing to honor their social contract (read: not stopping inflation, which they can’t stop from happening). Gref shot back working in his love of business terms that, in this case, unintentionally say more perhaps than intended:

“Generally, the client-centric nature of the state and terminology of ‘screwing’ the state don’t really fit, especially on the part of the state. All the same, the state establishes the rules of the game and business should play by them. Then we need to further discuss them: either business doesn’t follow the rules of the game, and maybe it’s not good enough, or the government is not good enough because it has established insufficiently transparent or effective rules of the game.”

On top of these open criticisms of state policy and the regime’s approach to both COVID and economic policy more broadly, Aleksei Kudrin and Anatoly Chubais openly spoke of the challenge that the specter of peak oil demand poses for the stability of the Russian economy and Russia itself. United Russia deputy Andrei Makarov, head of the budget and taxation committee, came out swinging on the state’s failure to adequately consider living standards and the investment climate ironically quipping that “the first step’s been taken — it’s the third day of the forum and no one’s been arrested.” There’s clearly a new level of panic about how bad the situation’s gotten and recognition that what’s always been a dicey investment climate with some upside has become too disorderly and risky for even local firms to make sense of heads or tails.

Looking at Levada for some perspective, similar % of Russians now believe the country is on the wrong track as ahead of the Bolotnaya protests — note that aggregate levels drop as the political system becomes less competitive, which we need to factor in for respondent biases:

Black = on the right track Blue = on the wrong track

What’s perhaps most telling is that the uptick probably is itself a bit of a base effect from how bad last year seemed in March-April. It’s hard to imagine it’ll continue to climb as people discover they’ve been screwed over by landlords, won’t see their wages rise enough against inflation, and so on. That so many elites are trying to use SPIEF as a platform, not only to lobby foreign businesses to “help us,” but to flag to the regime that they’re losing the plot goes to show just how incapacitated and out of touch Mishustin’s efforts appear to be. He’s effectively announced Gorbachev’s uskoreniye without any gas in the tank. Conservative reform in Russia always fails, swallowed alive by rentiers, rogues, imperial dreams, and the dissent it creates. More and more people seem to grok that things are falling apart. Whether they can influence the Kremlin, however, is a different matter entirely.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).