Really-Existing State Capitalism

The hollowing of Russian democracy is tied up in the expansion of state capitalism

Top of the Pops

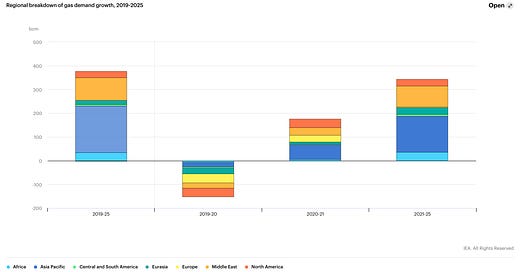

As I expected, the potential sanctions packet leaked to Bloomberg from the Biden administration doesn’t touch sovereign debt, once again confirming that sovereign debt — something the US Treasury has never wanted to target — will not be touched beyond the existing measures in place. RIP whoever claimed to have insider information or that “markets are often wrong to underestimate sanctions impacts.” The truth is markets are often wrong. Period. They also rarely follow the narratives imposed upon them with the level of precision business reportage, especially in a country like Russia, implies. But the sell-off from OFZs had a basis in the macro environment and rotations of investor positions as much as sanctions fears, which I always felt were an odd fixation since just 3 weeks ago, equities markets reported foreign investors were shrugging off sanctions risks looking for value. Equities aren’t sovereign bonds, obviously, but the larger point is that the market has been very noisy and it’s difficult to ascribe the results beyond a few days’ turbulence to the “Putin is a killer” comment and Biden’s cryptic, but boilerplate warnings. So instead of sovereign debt, Biden’s team want to target people close to Putin — this would be a nod towards Navalny’s team as well — and hit Gazprom subsidiaries. The US is going as far as to appoint an envoy to negotiate a deal with Germany to kill Nord Stream 2. If we pull the IEA’s adjusted gas demand growth forecast for 2021-2025 and assume it’s close to the mark, European demand has basically peaked:

The Asia-Pacific and the Middle East are doing the lifting, same as oil post-2000. But if European demand isn’t expected to grow significantly, the need to expand the pipeline capacity to Europe looks a bit flimsier (though it doesn’t invalidate the commercial logic of NS2, despite its critics’ claims otherwise). But even with damningly lackluster EU recovery spending levels and the latest German legal action against the fund, rising carbon prices in Europe will facilitate higher levels of investment into energy efficiency gains, improving heat retention and efficiency for homes, or else fuel switching where possible. It’s an open question what that looks like given the bizarre attempt in Germany to cut nuclear output. I’m still inclined to see more fuel switching occur, particularly since carbon adjustment on top of taxation will raise costs to use Russian natural gas as well.

What’s going on?

The government’s analytical center is now warning that Russia will pay if it doesn’t quickly develop an adequate system to report carbon emissions levels because EU importers will be forced to use high estimates to assess adjustment levies. As of 2023, the EU’s schema is supposed to take effect, creating a looming “policy cliff” without quick action. The government can, of course, plead for leniency from EU importers because of Russia’s dependence on carbon-intensive practices, hydrocarbon sector, and lower level of economic development, but it highlights just how little sovereignty Russia has on transnational economic matters of this nature. The exact economic impact is quite difficult to measure without more concrete policy proposals to assess, but the EU plans to completely eliminate oil from its energy mix as quickly as possible after 2030 while natural gas’ share will fall to 10% by 2050. Unfortunately, the changing forecasts for gas are all accelerating the timeline for its obsolescence, not suggesting it’ll last longer. Even Elvira Nabiullina’s warned that climate change poses financial risks the system will have to stress test for, and that includes large changes in capital flows due to an evolving policy environment. The story here is the absence of a policy agenda around Mishustin at a moment when it’s evident the direction of travel will soon affect the Russian economy. Some of that is down to just how many fires Mishustin is putting out, but it’s also a reflection of the increasingly negative influence the presidential administration seems to be having on economic policy.

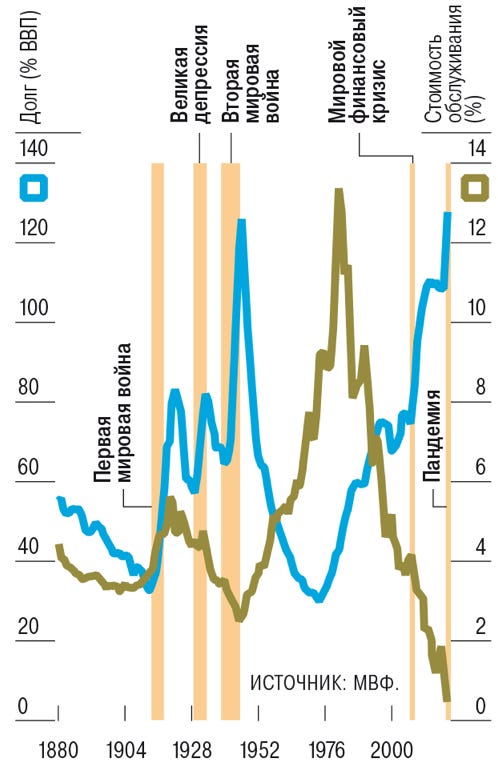

Kommersant’s writeup of the IMF’s latest review of sovereign debt handily dismisses the fear-mongering about borrowing embedded into Russia’s guiding economic security documents, though it doesn’t mean to. If sovereign debt is so bad for developed economies, why is it that debt servicing costs are at historic lows? The LHS is debt as % GDP and the RHS is cost of servicing as %:

As we can see, debt levels are analogous in % GDP terms to where they were in WWII, yet the costs of servicing them in % rate terms are near 0. There are limits to monetary sovereignty when you aren’t printing the US dollar, but the interest rate paid on sovereign debt is ultimately a political decision and the broadly disinflationary forces contributing to the global economic balances Russian policymakers are supposedly worried about — they never seem to address Russia’s role in perpetuating them in Eurasia — have forced the economic consensus among OECD members to evolve. Put another way, international investors will still want higher-yielding debt as part of their portfolios, which will buoy OFZs and Russia’s macroeconomic standing so long as they can buy them. However, what investors understand to be good macroeconomic policy is changing significantly. The loudest goldbugs taking the more Russian view on debt and equity valuations are, in fact, techies terrified that growth in the real economy will rob them of their wealth. They’ve gotten rich by selling themselves as drivers of growth in a world of demand and wage stagnation. At some point, the more orthodox views of the competency of the Bank of Russia and Russia’s finances will come under closer scrutiny as we shuffle through what is a paradigmatic shift in economic thought, at least in the West and among its leading international economic institutions.

MinEkonomiki wants to boost investment into utilities at the local level by banning state and municipally-owned firms from taking part in concessions. The proposal pairs the ban with moves to simplify procedures to move property that has no registered owner into private ownership. The latter is the real opportunity for private capital since there’s still a massive amount of pipeline and power infrastructure left from the Soviet period without a legal owner. The flip side being that many consumers, particularly in the most remote parts of the country but not always, effectively get part of their utilities for free by tapping into these objects without utilities operators being able to track what’s going on and swallowing losses on their balance sheets. To help address this, the reform would also allow private investors to take on greater than a 50% of the asset being acquired to then be put to use while extending the registration deadline for the asset from 1 year to 10 years and also making the municipal authority responsible for “formalizing” the asset alongside the private investor. It’s actually a decent approach divvying up responsibility more equitably and allowing private operators to operate more profitably. It’s exceedingly difficult to properly value assets that aren’t legally registered to an owner, and they default to local public ownership if the private operator fails to register it, creating a rotating opportunity to generate rents from the local government without increasing investment levels. There’s just one problem for MinEkonomiki: private operators inevitably try to raise end prices as much as possible to maximize their own rents from owning key infrastructure, whether that’s by overstating their operating costs, reducing investment levels and interrupting services, or through old fashioned graft. This is the rare relatively well-designed reform proposal, but one that will run up against political pressures to keep prices low.

The Duma is now debating a bill that would create yet another category of state secrets to be applied to ‘service secrets’ in the military that applies to military maneuvers or actions, but will not be classified at the same level as state secrets. The relevant organs — Ministry of Defense, FSB, FSO, and Rosgvardiya — will publish their own registers of what qualifies as classified information. It’s an update to an existing 1994 government decree. By itself, it’s not a remarkable development. As far as I can tell, it’s an attempt to create a new administrative tool to enforce operational security requirements to prevent more information leaking out to the public or online. Outfits like Bellingcat might claim credit for scaring Moscow despite the fact that they provide convenient avenues to leak information and generate a wall of noise about intelligence operations or the lack of professionalism of Russia’s military or security services that don’t track. What’s most important, however, is that the reform, however long-needed it may be, furthers a long-running dynamic whereby more and more information that would contribute to sanctions risks of any kind as well as accountability for the actions and corruption of military or security officials is being hidden by diktat. One can also see it as a means of inflating the threat perception in the West to maximize the psychological value and effect of the country’s continued financial commitments to its military and security services. Either way, these reforms often generate “mission creep” once the relevant organs realize there are gaps.

COVID Status Report

8,672 new cases were recorded alongside 365 deaths. The decline plateau is a lot more evident now in the official data despite headlines harping on new cases below 9k coming out now:

Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow Black = Moscow

If it picks back up towards November levels, presumably we’d see foot traffic at malls decline, at least marginally, hurting consumer demand (and supporting e-commerce). The anti-COVID immunoglobulin just worked up has been certified for clinical trials. It’s sure to factor into the public health strategy if it works. More interesting to note is that Germany has begun preparatory talks with Moscow about Sputnik-V supplies according to Regnum. Not only does this contradict the European Commission’s stance, it raises the possibility that by the time an agreement is reached if it is reached, cases will be surging once more in Russia. As of April 6, the official data collected by Our World in Data showed that just 5.61% of Russians had received at least one dose. That’s just plain terrible given the speed with which Sputnik was developed.

The Tax Man Cometh

I’ve been reflecting recently on the arc of Russian political economy since the 1998 default and the parallel change in the domestic politics of growth, redistribution, and reform. One can begin to trace major moments at which things changed in some way, or at least the seeds of change were sown, with the Levada Centre polling on public attitudes towards the United States. Thanks to Anton Barbashin for posting it on Twitter this morning:

Public attitudes are remarkably durable and bounce back, but the public’s feelings towards the US take big hits over Yugoslavia, the invasion of Iraq, the invasion of Georgia (coupled with the global financial crisis), and the annexation of Crimea, war in Donbas, and ensuing sanctions. The recovery the last time has been much weaker, likely because of sanctions don’t make you friends but also because of how the regime’s economic policies have moved further and further away from emulating western reforms or the failures of the partial efforts to apply shock therapy and privatization in the 90s. Compare this to Putin’s invocation of democracy and you see a related development arc — shout-out to Olesya Zakharova who wrote up her dissertation research for Riddle. Here’s the link for her full dissertation. Putin’s evolution from his first federal address is stark:

“But our position is extremely clear: only a strong . . . effective state and a democratic state can protect civil, political, economic freedoms, [and] can create conditions for people’s prosperous lives and for the prosperity of our Motherland "

Even if it was couched in the language of reforming and rebuilding the state’s capacity to govern, the power of democracy as a construct was politically useful and important. As Zakharova puts it, it was a ‘fundamental principle’ that would contribute to how Putins 1.0 and 2.0 cast the consolidation of state power. The relationship between ‘democracy’ as a fundamental principle and state capitalism is less clear. In the wake of the Munich Security Conference speech in 2007, then first deputy minister Sergei Ivanov promised liberal economic policy through 2020 at the St. Petersburg Economic Forum. ‘Liberal’ still had cache so long as it was tied to attracting foreign investment, but the energy sector had just been consolidated in state hands or at least under state leadership at precisely the moment that the Russian oil sector tax code ran afoul of the price rally. Production actually slightly declined in 2007 as effective tax rates shot past 100% since no one in 2001 thought that oil prices would rise much past $35 a barrel, let alone soar towards $100 a barrel and higher. The state was profiting handsomely, which was the point: the rents generated by state-owned resources and firms already dominated fiscal politics and future development plans. ‘Liberal’ economic policy, however, was still the operative goal of Kudrin’s team at the Ministry of Finance and those similarly inclined. They wanted more privatization, better functioning markets, greater economic complexity to reduce resource dependence, and a de-militarized foreign policy to the extent possible to buy more space for socioeconomic development, especially since the commodities boom had already begun to filter back into the economy negatively by 2007. They held on during the crisis years under Medvedev.

The Bolotnaya protests fueled a shift in Putin’s rhetoric upon his return to the presidency in 2012, calling democracy “compliance with and respect for laws, rules and regulations” rather than a foundation for modernization efforts. Six years later, he’d all but given up the pretense of democracy rhetoric. At the same time, Kudrin’s exit to be replaced by Siluanov in 2011 heralded a more conservative, statist bent at MinFin. Unlike Kudrin, Siluanov happily enjoyed the spoils associated with his participation in Alrosa, and even Elvira Nabiullina’s 2013 appointment to the Bank of Russia was foregrounded by time heading MinPromTorg and MinEkonomiki, institutions which may promote ‘liberal’ policies but have historically protected business interests in a manner not exactly conducive to strengthening competition or looking out for SMEs. Her time at the Bank of Russia, oft touted as a masterclass in effective central banking, has been a masterclass in applying the strictures of authoritarian monetarism even when calling for more ‘liberal’ market policies. She’s done so ably, and a remarkable job with the bank sector cleanup since 2015, but the consensus that applauds the bank has begun to change with this latest global crisis. The shift in Putin’s democracy rhetoric paralleled a more expressly statist, neoliberal austerity consensus for Russian economic policy that has only intensified to this day as the facade of ‘democracy’ has ceased to be a legitimating discourse for modernization and instead a tool to repress and divide political opposition to the extent possible.

So how does that fit with the timeline of spikes in sentiment towards the US? I think one can reasonable infer the large dips, short they may be, from the late 90s and 2000s reflect public anxieties and responses to perceived or real American unilateralism. The invasion of Iraq was particularly egregious among elites for the simple reason that the US granted itself the right to use force in a manner so wasteful, short-sighted, and unnecessary as to render criticisms of other nations acting unilaterally to assert their interests absurdly hollow and blatantly self-serving. When Dmitry Medvedev assumed the presidency as the country reeled from the shock of the Global Financial Crisis, his governing ‘raison d’être’ rhetorically was modernization to prevent such a crisis from ever hurting Russia as badly again. From Adam Tooze’s Crashed:

“What had made Russia so vulnerable in 2008 was its lopsided integration into the world economy: on the one hand, its excessive reliance on oil & gas; on the other hand, the corrupt culture of capital flight . . . What Russia needed was economic transformation, and for that it needed not less but more interaction with the world economy and above all its technological leaders.”

Medvedev understood the fears Kudrin and similar systemic liberals had. Future growth would be weaker and weaker without structural reform, a process seen across Eurasia after each respective commodity shock since 2000. Russia finally acceded to the WTO in 2012 largely thanks to Medvedev’s efforts, within the constraints he faced, but the political benefits were limited by the recession that struck in 2013, followed by the crisis of Ukraine and ensuing protectionism. The lesson clearly internalized by the Russian elites that began to assume posts setting economic policy after Kudrin’s departure in 2011 and across the security/military establishment was that Medvedev and the liberals were wrong. Integration was a political threat without control, or at least one to be profited off of, and could only be managed effectively by a strong state guided by conservative policy. Since they couldn't rollback free flows of capital, both to protect the interests of rich elites and calm foreign investors, they were beholden to the logic of austerity that swept across the EU in 2010-2011 and the challenge to democracy it entailed alongside the regime’s repressive turn. One can see the results a decade later when checking current polling on attitudes towards the US:

50+% of those under 40 have a good opinion of the US, a figure reaching 65% for those 18-24. The erasure of ‘democracy’ in practice and discursively from Russian politics has paralleled the hardening of its economic policymaking, itself presaging and reacting to the explicit turn against the West first started in Georgia August 2008 and then continued after Medvedev’s departure from the presidency. In place of more integration with the global economy’s technological leaders, badly designed “Buy Russian” policies subsidized by trade surpluses maintained at the expense of standards of living lead the way. Those hurt most by failures of economic policy since the crucible of 2008-2009 have the most positive view of Russia’s main geopolitical rival and threat, which alters the future discursive terrain of how terms like ‘democracy’ or ‘liberal’ can be deployed by those in or outside the political system critiquing it. What Konstantin Remchukov somewhat clumsily labels a fight between American expectionalism and Putin’s exceptionalism is, I think, reflective of the absence of economic logic from multipolarity as a concept and the regime’s insistence that Russia be remain a peripheral economic player while playing the part of a Great Power on matters of high geopolitics. These issues and perceptions are deeply interlinked.

The Biden administration’s new campaign to establish a global minimum tax rate for corporations and allow national governments to pocket the difference from tax havens is precisely the kind of initiative the regime hates — it’s multilateral, strengthens the cohesiveness of the ‘West’, and invests the US with a primacy Moscow cannot challenge. It defies the often easy, often accurate narrative of America as a rogue power accusing everyone else of being a revisionist, even when it’s in fact an example of Washington undertaking hegemonic adjustment to maintain its own primacy. These agreements challenge the sovereignty of individual states by force of economic and political gravity, and make future agreements on carbon adjustment and carbon tax harmonization all the more reasonable. Further, the initiative provides more fiscal room, in theory, to further tilt the world away from the neoliberal consensus that otherwise casts Russia’s macroeconomic management in a positive light. Post-Medvedev, Moscow laid its bets on state capitalism prevailing as a means of ensuring sovereignty and projecting power. Post-Trump and hopefully soon-to-be post-COVID, it’s becoming clearer that in the Russian case it’s ill-suited to do either.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).