Top of the Pops

Mohammed bin Salman noted in an interview that talks are underway with a “leading global energy company” to sell a 1% stake of Saudi Aramco — estimated to be worth somewhere around $1.7 trillion — and has set off a wave of speculation. Who wants to own 1% of Aramco? It’s a tiny equity stake. It’s a good reminder, however, that while the shale revolution killed off political risk premiums for oil prices and ‘de-politicized’ the market to a considerable extent, the looming threat of peak demand ‘re-politicizes’ it. High cost producers that can’t afford to idle capacity are at risk, as are publicly-traded firms unable to address investor fears and demands that they cut emissions to zero or else go carbon negative in time. The EIA demand forecast, I think, probably gets close to the likely demand recovery timeline with the caveat that the US pivot on AstraZeneca vaccines may help emerging markets recover more quickly:

By the end of 2022, we’ll be marginally above 2019 demand levels assuming this pans out. US shale isn’t going anywhere, even if it never manages to replicate the same heady pursuit of output over profit, but assuming it becomes less reactive to price, then future increases in output will hinge more heavily on MENA output — Russia, due to sanctions and its own geology/geography, is unlikely to raise output past 2019 levels to any significant degree, if it ever does. So say you’re an international firm trying to maintain oil & gas cash flows to finance a more expansive pivot to focus on trading operations and renewables/utility investments, Aramco might be attractive. BP’s already saddled with its near 20% stake of Rosneft aware that Russia’s lackadaisical approach to the coming carbon pricing storm will start to cost it. The best it could get was a toothless agreement to cooperate on carbon management and sustainability that practically kicks the burden onto BP. Nationally-owned firms are going to dangle their equity for political purposes. Unlike Russia, Saudi Arabia has an easier time dealing with investor fears — there aren’t sanctions risks and it’s built up a huge reservoir of lobbying support in Washington and London. MbS acknowledges peak oil in Russia is Saudi Arabia’s gain. The OPEC+ cuts have benefited Saudi Arabia far more than Russia, which has had to sacrifice intermediate domestic demand subsidizing or supporting other sectors to pull it off while its fiscal regime takes most of the upside from higher prices above $35 a barrel. But as Russian output enters decline in the coming years, its political incentives to be an involved security partner in the Middle East seeking some sort of clout to help manage the market will only intensify. When we talk about oil post-COVID, we need to rethink what the risk premium represents, whether that be discounts on equity valuations due to emissions, opportunity costs to ‘recycle’ equity stakes into green investments at the national level, or else the unintended domestic economic costs of output restraint. In other words, the risk premium isn’t about the barrel anymore. It’s about all the stuff behind it. And any attempt to soak the market for prices again, even in a world where private investors doubt oil & gas projects, will just accelerate fuel switching now that the alternatives are truly competitive and receiving more policy support.

What’s going on?

For those who’ve watched Sino-Russian trade closely, you may recall that in September, Putin ordered the government to ban the export of unprocessed timber or else low-quality wood. It’s a hot button political issue in the regions across Siberia and the Far East — by October, record levels of timber were being exported to China and local businesses and many locals see it as a rapacious trade since China has restricted logging domestically and instead sought to plunder Russia’s natural wealth. The government’s now considering offering a 10% discount subsidy to households and builders buying lumber home construction kits worth up to 3.5 million rubles ($46,672.50) to keep more business domestically, increase the marginal profits retained in Russia through value-added production, and make people forget that forests are being felled without much environmental concern because they’ll be selling to other Russians instead. The main critique is that the price cap is too low for the subsidy to have an appreciable effect — the subsidy is paid out by MinPromTorg to the bank issuing the credit and taken out of the principal owed. The cost to the budget is estimated at 360-400 billion rubles ($4.8-5.35 billion) annually, analogous to the one-off social spending package from last week. The forecast reported from Kommersant is that that money would increase housing sales by 1,500-2,500 homes a year given the price cap and rising prices nationally. That’s an insane amount of expenditure for little housing gain and would also likely pressure housing prices upward if consumers use the subsidy to cover renovations instead of buying complete homes.

Consumer expectations surveys from the Central Bank show that expectations and spending outlooks are getting worse fast and that the consumer side of recovery is proving to be a myth. Fears of an inflationary spiral are hitting households hard and many are starting to withdraw more of their collective 30 trillion rubles ($400.5 billion) parked in bank deposits out because the current rates on deposits lag inflation. Deposit rates have to go up:

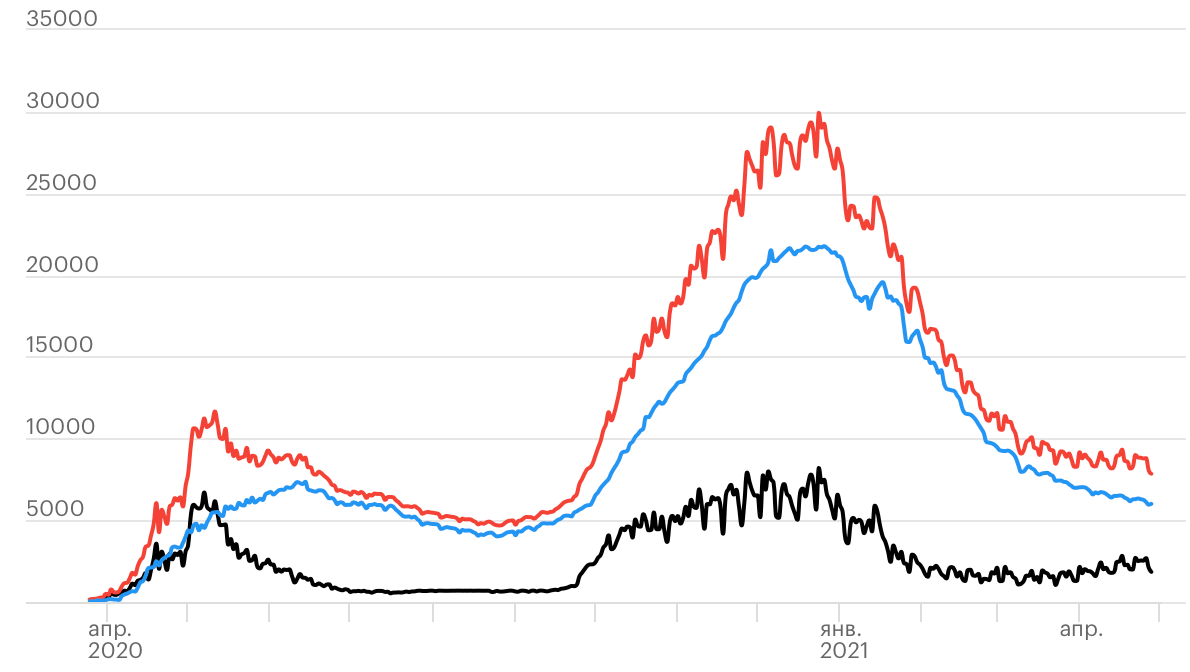

Gray = expectations index Red = consumer confidence index Blue = current state (of affairs) index

These are intended to be measures showing relative levels dynamically. Anything under 100 is bad news for trends, but the expectation figures generally come under 100. As we can clearly see, the recovery’s quite weak — expectations and consumer confidence far overshoot the index intended to reflect the actual state of the economy. On that front, things are barely better now than they were at the worst of the initial COVID shock. Expectations and attitudes also appear to have peaked in February-March. The social spending announcement last week might nudge that up slightly, but confidence is the real concern. Consumers now expect 11.9% inflation for the next 12 months vs. the figure closer to 6% from the official forecast. On the one hand, that encourages anyone who can afford it to make big purchases like a car or house now if they can. On the other, the rush to do so just worsens the squeeze on prices and demand for food doesn’t work that way. Plus you’d think that consumers would have a sunnier outlook given that some banks have reported a combined 62% increase in savings deposited with them during the pandemic. In reality, people have been living in economic crisis for 8 years now. There’s no consumption boom coming, especially not with inflation out of control and generally worsened by poorly designed price controls for basic goods.

Fights over the meaning of ESG norms, a recent arrival for Russia’s financial markets, are now breaking out over the financing of Rosatom’s Akkuyu plant in Turkey. Former problem-child bank Otkrytiye extended a $500 million line of credit with a 7-year maturity after Sovkombank offered a $300 million line of credit in Feb.-March. Both banks say the project’s up to snuff, but the yawning absence of clear guidelines and lack of pressure for the government and presidential administration to proactively ‘problem-solve’ means that the rules of the game are up for grabs. When Sberbank extended a $400 million line of credit in 2019, it didn’t even refer the project for internal ESG review because the processes didn’t really exist until 2020. There aren’t yet any rules to distinguish the primacy of emissions reduction — nuclear power is obviously better on that front — from other ecological risks. Given that regional governments have been handed the task of implementing any carbon trading schema as they arise and the explosion of green financial instruments and issuances abroad, Russian banks need to keep pace if they want to be able to finance projects abroad in the longer-run. Nuclear is excluded from the green taxonomy for European ESG standards, which are the ones Russian banks have to follow the most closely in practical terms. That doesn’t mean the interest rates for Rosatom are bound to skyrocket — after all, it’s probably Russia’s most competently run SOE and the expansion of nuclear exports is central to Russia’s energy strategy and ability to adapt its over-reliance on energy diplomacy to the energy transition. The company’s Build, Own, Operate (BOO) model relies on discounted state-backed credit to build capacity in emerging markets with higher default, currency, and political risks. But if ESG dictates nudge rates upwards (eventually), state subsidies might have to rise as well to offset that.

The Central Bank notes that for Jan.-March, the number of false US dollar notes in circulation found by authorities reached a 20-year high. There was a 15-fold increase for all fake foreign notes found in 1Q 2021 over 4Q 2020, 98.2% of which were dollars. The total cited seems low — 6080 notes in total — but given the large gaps in state capacity, particularly given the large share of financial activity such as lending carried out in the informal economy, my guess is that it’s a significant leading indicator. Apparently there haven’t been this many total fake notes circulating found since 2010, but the surge in USD shows that Russians still see it as the safe foreign currency of choice. The number of false overall fell by 32.3% from 4Q 2020, however. Inflation is changing the incentives for counterfeiters and anyone trying to find hard cash floating around — so long as deposit rates lag inflation, the historical preference for cash in hand will only strengthen. It’s just that it won’t be rubles doing the circulating since you need so many more to buy big ticket items and they’re devaluing far faster than the USD. The net decline isn’t necessarily a good sign for that reason and while marginal statistically, probably plays a part in worsening consumer outlooks.

COVID Status Report

Russia recorded 7,848 new cases and 387 deaths yesterday. The dip is down to variation in the data from Moscow put out by the Operational Staff. Despite the appearance of good news, the WHO is warning of a ‘soft plateau’ for cases at the same time that Moscow data shows cases are rising in Moscow again when you pull the 7-day average and ‘unofficial’ data shows a 3rd wave is developing. To give you an idea of the policy focus now in the Duma, speaker Volodin has demanded compensation from European countries from which COVID spread into Russia:

Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow Black = Moscow

COVID hospitalizations for yesterday were up 1% week-on-week in St. Petersburg, with the more worrying stat that the number of patients recovering from it suddenly dropped 39.74%. That could be statistical noise, but it’s worrying if we see the same trend elsewhere outside of Moscow. St. Petersburg and Moscow alone can sway the numbers considerably, but also are travel hubs and the best equipped to handle surges of infections. For now, the Operational Staff is adamant that any data showing a 3rd wave is ‘absolutely unreliable.’

The Eek-onomics of Optimization

Few are the leaders of Great Powers who’ve suffered political ignominy with such aplomb as Dmitry Medvedev. As I wrote a long, long time ago, Dimon became the political equivalent of Tarantino’s gimp from Pulp Fiction after Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012. As Mark Galeotti well notes:

He’s now seated in his semi-obscure role as a deputy on the National Security Council. The council is headed by Nikolai Patrushev, an über-hawk who earlier this month accused the US of controlling a network of laboratories in foreign countries making biological weapons strangely close to Russia and China’s borders. Safe to say that Medvedev’s softer, systemically liberal instincts have limited reach there. But yesterday, he made a classic plea that captures the plight of anyone calling for more proactive fiscal policy and state expenditure. He called for the more ‘economical’ use of state research and science expenditures in the wake of Putin’s announcement last Wednesday that an additional 1.6 trillion rubles ($21.42 billion) would be allocated to civilian research through 2024. For context, the annual science budget for 2021 is roughly 405 billion rubles ($5.42 billion). Russia’s R&D expenditure has a languished at about 1% of GDP, trailing competitors by a significant margin and compounded by the over-concentration of research in the defense sector that has limited civilian applications.

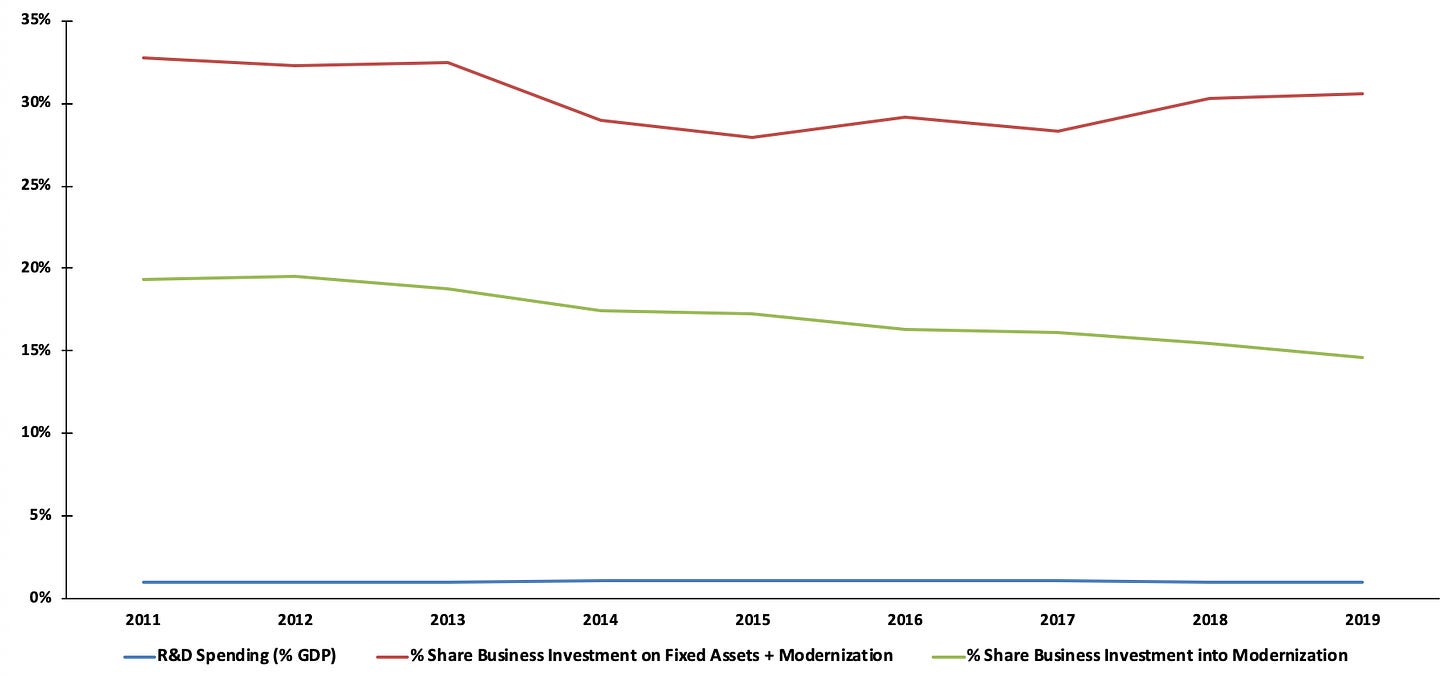

Optimization is a word thrown around since Mishustin became Prime Minister and replaced Medvedev in January 2020, and it reflects the claims made by Medvedev. The lack of ‘synergy’ between various research efforts is a reflection of poor institutional arrangements, inefficiency, and corruption and resources are incredibly limited because of the bunker mentality that Russia’s brand of statism fosters. Deficit spending threatens to increase the relative level of dysfunction because it increases the opportunities for graft and potentially increases the private sector’s claims on foreign currency reserves, which are needed to insulate the financial system from geopolitical risks. Medvedev’s comments struck me because they suggested that the new spending that was announced wasn’t seen as a significant increase, but still carried risks. If you compare R&D spending — basically all directly or indirectly backed by state spending or financing — to the state’s consumption share of GDP, you can see that the announced increase through 2024 is really just intended to claw back % losses that kicked in after 2016 in tandem with a slowdown for military spending. On a % basis, R&D spending in current prices was lower in 2020 than it had been for 2011-2014 during the most intense phase of the military modernization program that first began in 2007:

I thought to check this because Medvedev’s statement reads like a guy pinching pennies to keep the boss happy, not someone excited to see an infusion of cash help build up the state’s capacity to stay competitive and support innovation. There was a nascent policy initiative back in January from Rospatent to introduce tax breaks for firms’ IP that enters production and inventory in order to stimulate private sector R&D. Absent was any discussion of the escalating effects of amendments to the legal code intended to ensure ‘economic security’ and how business conservatism without demand stimulus also kills IP investment. As a Novaya Gazeta investigation notes, members of the security services used the legal code to go after nearly 4,000 businesses between 2010 and 2019 and seized assets and money on questionable grounds using just one law in the codex. If a private sector firm comes up with an innovation that has any potential value to the state, they’re inherently at risk of being raided, curtailing the range of sectors where innovation takes place and further concentrating the important projects in the hands of SOEs, natural monopolies, or firms that effectively act as extensions of the state. Throwing more money at the problem, however, isn’t the go-to response not so much because of corruption risks by themselves, but because corruption can worsen inter-agency and inter-firm conflicts over resources and become a national story causing dissent or affecting local politics. The tax cut is the easier path and better fits the Kremlin’s preferred managerial approach: kick as much responsibility as possible to people lower on the food chain and let them sort it out. The state gets to assure businesses their profits will be safe while actually undermining the fiscal capacity it jealously guards as the prime mover in the economy. What’s obvious is that the private sector isn’t filling the gap:

R&D is trapped at the 1% bound pre-crisis, but the % share of business investment going into modernization — often covered by imports but where domestic import substitution provisions could help — is declining while the overall spending on plant has fallen, but less sharply. These are proxies pulled from Rosstat data, which is always finicky and methodologically messy. It gets even weirder when you break out national income (current prices) into labor’s share vs. the % tax take and % accumulated as profits/revenues:

The relative tax take in % terms has declined since 2011, which might reflect lower oil prices but also goes to show that tax breaks can only do so much in macroeconomic terms if the state’s still obsessed with reserve accumulation as geopolitical insurance. Topping it all off, capital outflows are continuing apace while the current account remains compressed from the oil price environment and oil production cuts:

It’s not ‘news’ that optimization is the policy path of least resistance. What’s surprising upon closer inspection is how ill-suited the tax cut and efficiency-centric approach is given the overall environment. There’s a compelling case to be made that an increase in spending could create enough additional state capacity in time to offset some of the negative drag from corruption and institutional informality. Medvedev’s a human palm tree who sways with the needs of the moment, but his comments point to a problem for analysts covering Russia: when does policy paralysis and economic crisis become elite crisis? Optimization of research institutes and spending approach suggest it may be closer than many assume.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).