Top of the Pops

Crisis in Armenia continues apace. Members of the Dashnaktsution party stormed into a government building before calling off the protest action in a show of force that they could work their way into any ministry if they so wished. Pashinyan’s press secretary told the press that he lacked all the facts about Russia’s Iskander system when he commented, a remarkably clumsy attempt to save face and appease Moscow, which apparently is a bit a jumpy about the performance of the Iskander system and refuses to acknowledge that it was fired in the conflict despite video evidence to that effect. Pashinyan’s team did not confirm whether or not it was fired in the first place and Pashinyan himself called Iskander “one of the best in the world.” It’s incredibly difficult to follow accurately without being in the weeds on Armenian social media and daily political shifts, but the coverage in the Russian press conveys the sense that he’s swiftly moved to head off any internal dissent from the military trying to firm up support from Moscow knowing that it could be the end for him politically if he lost Moscow’s confidence given its ties and role with the Armenian military and security apparatus.

Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev has kept out of the conflict, retreating to the classic CIS dodge that the protests and political disruption are a domestic matter. The peace deal holding Karabakh together requires stability in Yerevan, stability which would be all the harder to win if Armenian political parties furious at the government for its conduct of the war visibly saw Baku cheering on Pashinyan. Armenian president Armen Sargsyan refused Pashinyan’s initial demand to relieve the head of the General Staff from his post. Pashinyan convened the national security council this morning to discuss how to address the situation with his cabinet and repeated his demand to relieve the head of the General Staff to Sargsyan. The question is how long the president can keep balking, especially since Sargsyan served as Armenia’s point man for diplomatic relations with the EU for several decades. It’s unclear which direction he’s leaning since Pashinyan’s been forced to tack back hard to Moscow since the war concluded, precisely what he’d won power to prevent in hopes of improving Armenia’s chances to turn to the West. It gets all the more complex now that the prospect of opening the border with Turkey, while not yet a concrete possibility, is at least on the political horizon. Aliyev has said that Azerbaijan wouldn’t object to it. The political blocs fighting now don’t correspond to any neat political fault lines concerning external powers, nor do they necessarily reflect the same constellation of factors that brought Pashinyan to power back in 2018. The strategy is clear — prevent the military from taking sides and ‘let the people’ decide by exhausting the opposition’s will and public support. For now, Pashinyan appears to be fairly safe, but Eurasia has a tendency to surprise us when we least expect it.

What’s going on?

MinStroi wants to expand support for small construction firms building housing projects in poor(er) regions with low profit margins. At present, companies are able to access subsidized credit to finance the construction of these projects when they’re worth up to 500 million rubles ($6.74 million), a limit it wants to lift to subsidize larger construction projects. The program’s aims are two-fold: improve housing shortages in poorer regions that aren’t attractive investments for firms and support small and medium-sized businesses. These loans can only be accessed by small firms operating in regions where the average income falls at least 15% under the national average and the project in question has a profit margin at least 15% under the national average — one wonders how exactly they calculate that figure effectively since in a higher inflation economy, even with stagnation, backwards looking survey data would lag changes. It’s a good initiative, but I would worry about rising costs for labor and construction materials creating significant price inflation and flat real wage and real income data affecting projected margins for properties depending on what the firms can convince others to pay them. In short, it’s another potential bubble within the economy, though one that doesn’t really pose systemic risks and carries socially positive externalities.

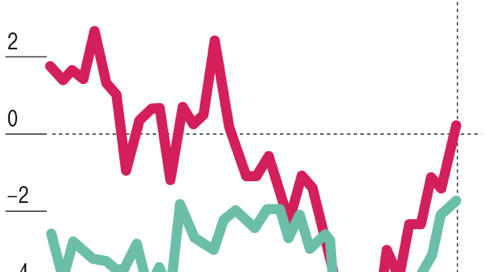

Business confidence data shows a surge for extractive companies and a lagging recovery for manufacturing/value-added production including refining. That lag has to be caveated, however, since levels are back to where they’ve largely been for 2018-2019 and could actually slightly improve on them during the initial rebound:

Title: Index of Business Confidence of Organizations (excl. seasonality, %)

Red = extractive industries Seafoam = manufacturing/value-added production

The number changes between January and February are just noise. The underlying trend is the story. Higher commodity prices have turned things around for most of Russia’s miners and drillers with hopes that either OPEC+ oil production cuts are rolled back, or else the cabinet will discuss further support measures for the oil sector to hold up intermediate demand. The story’s different for manufacturers/refiners who are more confident now than the have been for several years, but still aren’t seeing any particularly strong gains across the economy. Price inflation for basic goods across the broader economy continues, hurting consumers with the highest propensity to spend all of their earnings the most. That means that the most reliable source of demand — and greater confidence — in the year ahead will come from budgetary support, direct budget spending for procurement orders, and businesses otherwise wrapped up in support schemes. Boris Titov is still working to get the Kremlin to announce a new business support package. But austerity imposes a lower ceiling on how high producer confidence can climb given the correlation of forces.

The Ministry of Digital Development is looking to expand the credit subsidy program intended to stimulate firms’ digitalization of their operations, proposing to lower the minimum loan size to 5 million rubles ($67,437) from 25 million rubles as well as expand the number of lenders allowed to use the program from the current list of 20. Last year, 35 billion rubles ($472 million) at annual interest rates between 1-5% as companies coped with working from home needs and upgrades in digital infrastructure. On top of making the program more accessible, the ministry wants to up the domestic sourcing requirement from 60% to 70% to meet development goals replacing imports of software and hardware wherever possible. It’s yet another supply side measure to boost import substitution for digital goods and services, the question as always is where does the demand come from? Large firms like Russian Railways have jumped at the program since they have scale, won’t dislocate a lot of workers from investing in better equipment, and can marginally improve profits by doing so. It gets a lot trickier, however, for industries that provide an employment backbone for the regime’s support, an issue all the more tenuous now given the clear policy pivot to promote home ownership — and create a growing class of assets that could be securitized to finance domestic investment needs and that store wealth for Russians unlikely to see their incomes rise much without broader economic growth. Still, it’s a relatively affordable program and one to watch for the rest of the year as a proxy for aspects of sectoral import substitution.

Moscow is set to be the first municipality in Russia issuing green bonds to finance investment initiatives for ecological/environmental programs and infrastructure projects. It’s a sign of progress towards the incorporation of ESG guidelines into investing and domestic financial instruments, but as always in Russia, it’s not necessarily what it appears and seems to mostly be about greenwashing (at least at first). Per Vedomosti’s reporting, the Mayor’s office is foremost trying to use these bonds to finance projects already underway that would otherwise be cheaper to cancel. The hope is to issue 400 billion rubles ($5.4 billion) worth of bonds over the course of a year, but the catch will be that since it’s a novel instrument and they need to attract investors, the coupons offered on the green bonds will probably have to exceed standard municipal bond rates — 6-7% vs. 5-6% based off of OFZ yields. Andrei Loboda of IATs estimates a bond with a duration of 3-4.5 years would net yields of 5.75-7%. The biggest thing going for the city government is that bank deposit rates are so low thanks to Central Bank policy, so a coupon at 5.75%-7% would draw more interest from investors, especially as an inflation hedge given the key rate is lower than the current inflation rate for the year.

COVID Status Report

Cases slightly spiked up to 11,571 with 333 reported deaths. The messaging around levels of immunity in the population are getting confusing despite the drop in numbers. The absolute figures at the regional level show that cases are still (relatively) concentrated and there’s little reason to get too complacent just yet despite the world of difference from a month ago:

Rospotrebnadzor is briefing that only 5.7-6% of the population has immunity against COVID — about 8 or 9 million people. That doesn’t seem to match what you’d expect at the national level per the data given how weakly enforced or followed restrictions have been. But it matches the available vaccine data. What’s worse from Levada, the fall in cases now means that over half of Russians don’t think they’re at risk of getting infected, 28% say they don’t know anyone who’s gotten COVID, only 30% say they’re ready to get the vaccine, and 64% think COVID was created in a lab as a bioweapon. The hope would be that herd immunity will be reached nationally soon thanks to last year’s public health failure and the sheer number of people infected, presumably including a great deal who simply didn’t know they had COVID. The natural herd immunity explanation is the only one left to explain the case decline, barring some fudging the numbers and issues of administrative capacity. The ‘easy’ part of case decline is over, it seems. Vaccines have to do the lifting now.

Public Enemy No. 1

New survey data from NielsenIQ should scare the government and presidential administration: 69% of Russians report having to stretch their money farther from financial stress — 53% say that the pandemic is having a financial impact on them and of the 47% who say their earnings haven’t been affected, 16% are still more carefully watching how they spend their money. The Nielsen findings corroborate the observation that consumer spending in Russia is increasingly polarized between those who are feeling the pinch and those who aren’t, likely overlapping considerably with employment in service industries that weren’t terribly affected — law, finance, etc. — vs. consumer-oriented industries, the more secure jobs in the extractive sector, and so on. And on top of this dismal news, we’re no longer benchmarking the relative decline in standards of living against 2013 when economic stagnation became the structural reality of Russian economic policy as all of the surplus productive capacity from the Soviet period was exhausted and the workforce began to decline — that’s been a fall of roughly 4 million people per official stats in the last decade. It seems that real incomes are now at the same level they were in 2010 during the initial stages of the post-financial crisis recovery.

We can now officially say that the Kremlin has led Russia to a lost decade in terms of the material purchasing power of its population — I set aside quality of life which is a bit more complicated to measure. It’s remarkable that the gains from 2010-2013 thanks to $100+ per barrel oil prices were wiped out in 2020 since real incomes kept falling through 4Q, though nowhere near as fast the post-Soviet record of 8% between April and June alone. Consider also that these real income declines and supposed economic diversification from oil since 2014 show virtually no impact if we break out sectoral % share of business turnover from Rosstat data (2021 is just January and skewed by the 4Q spending effect and holidays whereas the others were based on averages from monthly data):

The ‘rest’ includes a bunch of smaller sectors so I condensed it, but is dominated by the power sector and transport, so the higher its share of economic activity, the more those sectors are basically draining money from elsewhere given that net investment levels fell from 2013 onwards and increased turnover for either tends to correspond to price inflation passed onto consumers elsewhere. Retail turnover’s share of turnover is relatively consistent — between about 36-40ish% — despite declining real incomes. But what that means is that the consumer sector is increasingly fragile while manufacturing’s share has declined slightly, which corresponds to the austerity measures taken to reduce spending more in % terms than revenues have been increased as a % of GDP as well as OPEC+ production cuts. Most telling of all is just how small the turnover in agriculture has been as a share of total economic activity, which means that while it’s grown as an export sector considerably — enough to affect the national balance of payments, though marginally compared to oil & gas — it’s not actually producing much knock-on demand elsewhere in the economy in the aggregate. Once again, the people hawking the diversification story don’t seem bothered by the lack of intermediate demand the industries they cite as success stories seem to be generating.

Since retail continued to account for around 40% of business turnover last year, it makes the pressures implied by this year’s inflation data all the more concerning amid real income decline. Since the year started, consumer prices have broadly inflated by 1.2% — 0.2% from Feb. 16-24 alone. Pasta’s up 2.3%, black tea is up 1.5%, frozen fish (theoretically cheaper with China’s now easing import restrictions) is up 2.6%, and chicken has risen a whopping 6.7% for the year-to-date. It’s inconceivable that there won’t be more respondents in polling citing financial stress in polls to come. Medication prices have also risen anywhere from 2-5% depending on levels of import dependence and domestic availability. And amidst all of this, Kremlin spokesman extraordinaire Dmitry Peskov has literally blamed the implementation of pension increases on the global economy despite the fact that 1 trillion rubles from last year’s budget went unspent and were cordoned off into extra-budgetary vehicles or deposited elsewhere. Pensions were indexed upwards 6.3% as of January 1, but those gains are evaporating under the weight of the current wave of inflation. There is some good news on that front, at least for foodstuffs. The Central Bank’s most recent monitoring update on financial flows shows that inflows into food production are notably higher than last year (or any year 2016-2020) chasing higher prices:

This lends more credence to the relationship between supply and demand driving inflationary cycles rather than the money supply, and again speaks to how the lack of investment supported by austerity policies since the business climate is weak and consumer demand frequently weaker worsens these bouts of price pressures. These increases also take time to show up as price deflation assuming this is real economy investment. But price deflation via investment into greater productive capacity requires the proper mobilization of savings for investment purposes across the economy. Apparently 44% of Russians are unaware that as of January 1 this year, they pay tax on accumulated earnings from deposits in banks in excess of 1 million rubles ($13,490). 17% don’t care cause they have no deposits, 27% understand the scheme (and are clustered in Moscow, SPB, and big cities), and on the whole, 74% of Russians aren’t going to refuse deposits. Those who knew have already adjusted, and those who aren’t particularly bothered or aware have yet to realize any losses. It’s a policy that makes sense in terms of trying to capture any accumulated gains from being wealthier, but seems likelier to hit middle class Russians than anyone else, those with some savings but not earning extravagantly off of capital gains elsewhere. The same polling shows that 42% of Russians don’t have an individual investment account and don’t know why they’d need one. The decision to tax deposits may spur more people to buy into the stock market or move their money elsewhere, which should theoretically expand the pool of equity available against which loans can be secured, capital raised, etc. However, the institutional distrust that many Russians evidently have for totally valid reasons undermines that strategy, and it’s hard to see this tax as proving popular if there isn’t any appreciable gain in terms of public services or spending from it, especially since every marginal increase in tax revenues corresponds to a smaller marginal increase in budget spending since 2014.

Against this backdrop, Boris Titov is pushing for a new round of business support measures with Andrei Belousov that would include tax amnesties for any companies earning under 2 billion rubles ($26.99 million) that saw their 2020 earnings fall 30% or more from 2019. He’d also like to write off half the debts of companies that failed to maintain 80% employment or else increased employment after July 1, 2020 on top of the current 2% subsidized credit program for distressed businesses. Basically, yet more supply side measures, admittedly welcome ones for SMEs, that have precious little to do with bringing back demand. He’s also proposing a progressive tax system for smaller businesses whereby the tax rates would rise with company and earnings size up to a point at which it would be uniform. It’s a great opening bid for small business and service business owners, but somewhat aside the question of how to save living standards so long as investment levels correspond to disposable incomes and consumer spending and a large portion of increased savings aren’t actually being lent or mobilized by financial and non-financial institutions as well as companies. Rather they’re stashed under mattresses and not circulating or being absorbed by consumer price increases while retailers face political pressures to reduce their own margins where possible. The Federal Antimonopoly Service just launched an investigation into egg production and price increases among producers as administrative resources are used to legally pressure companies into pretending that they’re just marking up costs and not also absorbing some rising costs themselves (sector dependent of course).

Navalny isn’t Putin’s public enemy no. 1. It’s the economy. The underlying data for recovery this year looks worse and worse upon close inspection, even if exporting sectors show signs of life. And the worse the economy gets, the more repressive measures will be used to control the public.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).