Top of the Pops

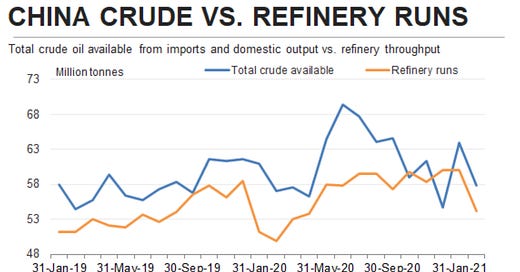

China’s back to storing up crude oil as refinery runs tick downward. This is a huge trend to watch for the oil price going forward in 2021, and provides a strong rationale to adjust the bull market case for oil in 2021:

There’s an important lag between when deliveries of crude oil are secured and when they’re actually “consumed” by refiners or else put into storage. This lag is generally several months, such that March deliveries were probably secured in December or early January (when prices were lower). The operating assumption is that with Brent crude trading around $65-70 a barrel, storage demand (i.e. ‘excess’ purchases over current demand levels intended to be drawn down when oil prices are higher) will weaken. China’s not going to be lifting up the oil market as much in the current oil price band by snapping up extra volumes otherwise not being consumed in other economies. The market’s bullishness is basically down to nerves — net long and short positions for oil futures contracts are basically even right now. JP Morgan expects shale output to rise since profit margins of $10-15 per barrel (or more) are hard to pass up. It’s a perfect storm despite Russia’s line that the market is balanced: sentiment is vague, ill-informed, and not borne out by futures positioning, higher prices in place with Saudi Arabia’s decision to hold off easing are beginning to tempt otherwise cautious drillers elsewhere, and China is no longer going to be the “consumer of last resort” holding up the market the way it did on the back end of 2020. Demand growth has to come from elsewhere as supply side measures, effective in the very short term, are running out of room to balance the market.

As of April 1, the export duty on crude oil in Russia is rising $8 to $57.60 per ton — clearly MinFin wants to capitalize on the moment and MinEnergo is onboard for now. That will provide a short-term infusion for the budget and more resources to be distributed to sectors in need. But there’s a stronger case for downward pressure on prices in the months ahead, especially if OPEC+ cuts are eased in April, which will inevitably roll back some of this gain. The oil tax maneuver remains incomplete with export duties set at these levels. Whether they complete it on time seems to be a function of how greedy MinFin’s feeling, though I lean towards the view that the implementation will accelerate once the “crisis” has passed. The decision to cut debt issuances suggests confidence that the budget is in fine shape, even if another burst of social spending is needed. But whenever Siluanov’s confident, it tends to mean the public are getting soaked for the good of the state. That can’t be a positive sign.

What’s going on?

In yet another twist in Russia’s municipal waste management saga, deputy minister Victoria Abramchenko is pushing for ministries, operators, and regional governments to work out a payment scheme for waste disposal that charges users based on their income level. It’s intended to be an extension of current plans to create differential tariff schema at the regional level depending on a region’s level of development. Everyone knows it’s a sham. There simply aren’t any means available to effectively structure such a system, particularly if levels of waste don’t vary that much per household past a certain income threshold, and it would require yet further federal subsidies to make it feasible for operators to take financial losses without charging richer Russians exorbitant fees. What’s worse, even the waste operators don’t care much for getting paid by individuals or companies because they’re making their money off of the regional and federal contracts they’ve won. Were they to actually charge every individual house and implement a tiered payment system, the sector would likely collapse unless federal subsidies were expanded. The systemic underinvestment in infrastructure makes it exceedingly difficult to actually serve every individual house as well, and it seems that direct contracts with users are the best means of paying for the actual physical volume of waste taken away. This is a perfect example of how the center’s failure to invest in infrastructure at adequate levels because of excessive fiscal caution has, over time, built up a capacity deficit that makes it all the more difficult to resolve a problem that launched a national wave of protest and organization at the local level in 2018-2019.

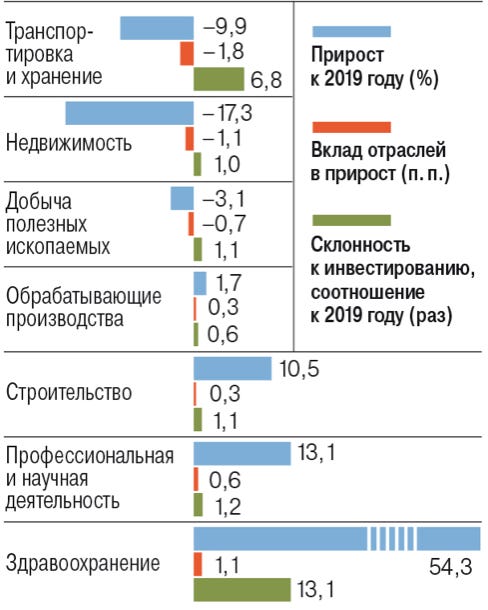

Data covering capital investments from Rosstat and the Higher School of Economics shows a very skewed and weak investment recovery. The HSE put out a commentary on business yesterday worth a look if you want more granularity (I’ve used it in today’s long column). The blue refers to general investment growth in % terms vs. 2019, orange is the sector’s contribution to growth, and green is the inclination to invest vs. 2019:

Descending order: transport and storage, property, resource extraction, value-added production, construction, professional and scientific services, healthcare

Construction is up, yet property investment is down bigly as is transport — the latter is huge given that COVID was a demand shock, not a supply shock, and even temporary interruptions in infrastructure investment cycles in Russia can have considerable consequences for logistical bottlenecks. The good news, of course, is that the net volume of investment — 20.1 trillion rubles ($275.27. billion) — only fell 1.4% vs. 2019, much better than the expected 4.3% drop. That these drops are so small goes to show how central the decision to continue federal projects was to maintaining investment levels and that a lot of money to be invested was just directed to other sectors/uses. But the drop hides the problem — investment levels and the GDP growth path pre-COVID were atrocious, with investment down roughly 10-12% off of its 2012-2013 peak. As a result, this data actually suggests things are going to look anemic in the year ahead since the sectors worst hit are mostly correlated to consumer demand, which will look weaker than 2019 by many measures because of falls in income.

According to an HSE survey, less than 60% of productive capacity in the industrial sector was utilized in February, the lowest reading since the worst of the financial crisis in 2008-2009. It was 65.3% in November and steadily fell to 59.8% in February, a trend that is worrying but tempered by the fact that February tends to be a month with lower utilization rates even in a good year. Economists are brushing off the news by reminding us that the maximum figure for the sector is about 80% and as long as it returns to growth in March, everything’s copacetic. The figure should be somewhat more alarming, however, given the concern about inflationary pressure. If inflation is already a problem when industries that drive a great deal of investment, hire more, and provide some production for consumers domestically are operating at less than 60% capacity and never operate at more than 80% capacity when times are good, then the revival of the sector should lift inflation. Note that all economies have some slack, but for instance, a similar measure of productive capacity in the UK was 85% briefly just a few years ago and more normally falls around 80% where wage growth and inflation are anemic. This is another way to say that in the aggregate, industrial production should be having a deflationary effect on the economy (unless a shortage of a domestically-produced good that can’t be imported bids up prices). A tight spot to be in if you’re the Central Bank or government wondering just how the hell you can get the current situation under control.

Export levels recovered by the end of 2020 towards their 2019 levels, with exports of construction machines and other types of machinery rising 12% and exports of appliances up 17% beating pre-COVID trends. Agro-industrial machinery production was up 6% alongside a 14% rise in agricultural output for 4Q 2020. Metallurgical exports also rose 3%. There’s more in the piece, but the big picture is that non-oil & gas exports showed strong signs of not just recovery, but potential for future growth. The current national strategy through 2030 aims to increase non-resource exports in real terms by 70% vs. 2020 levels as the original export aims set in 2018 by Putin’s May Decrees for 2024 have all been revised downwards significantly. It’s become quite clear that the regime hoped 2018 would have allowed space for a reset on economic policy that never came together. What’s more interesting to me is how these indicators of rising non-resource exports in the present environment actually reflect the failure of Russian economic policy. Aside from something like wheat or gold which have effective limits on how much is consumed domestically, the rise of machine and some consumer exports reflects the decline of Russian consumers’ incomes and lower levels of business investment. A nation’s current account is, in simplified terms, a measurement of how much it produces domestically vs. how much it consumes domestically. When you export more than you import, you produce more than you consume. When you import more than you export, you consume more than you produce. It’s quite possible that Moscow can make headway on some of its export targets through 2024 and 2030, but so far, the gains are primarily coming as a result of falling real incomes and domestic levels of consumption instead of competitiveness. That should alarm policymakers.

COVID Status Report

New cases came in at 9,393 with reported deaths at 443. Death rates still aren’t declining in step with cases, which which either means that there are more at risk people than expected or, much likelier, that total infections are still higher than the official data reported by the Operational Staff. Worryingly, Rospotrebnadzor confirmed new cases of both the British and South African variants with different mutations (but no sign of the Brazilian variant), though all infected parties are in isolation and it’s just a few cases. The bigger draw for news came from a leak that the US State Department leaned on the Brazilian government to reject the Sputnik-V vaccine. Many rightly cry foul, but to me, it seems a rather pedestrian and expected course of action differing little from whatRussia or China are doing elsewhere where if they can (of course, this depends on the country), never mind the EU’s bizarre antagonistic stance against AstraZeneca. The US has already launched an initiative to produce 1 billion doses elsewhere and I’m confident that there are parallel initiatives in motion though they may come to nothing. But it’s hard to ignore the blatant disregard for the public health of Brazil, especially given the history of US policy in Latin America, and it’s clearly a wrong and malevolently constructed policy. At least Moscow can rest easy as Duma speak Vyacheslav Volodin has set out an agenda to identify the countries safe for Russians to travel to by the end of spring.

Capital Crimes

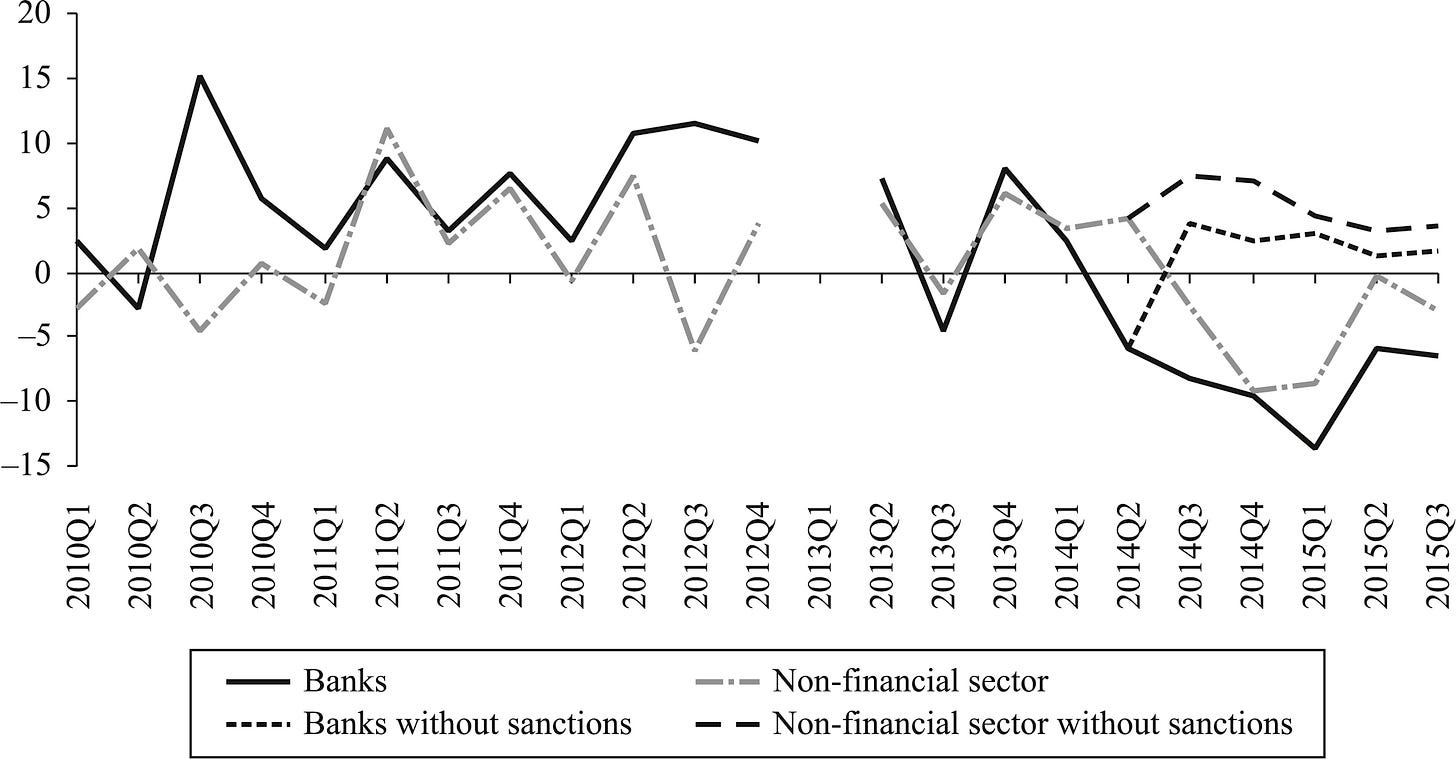

A new article published in the Russian Journal of Economics by Evsey Gurvich and Ilya Prilepskiy offers more useful evidence to make sense of the impact of western financial sanctions on the Russian economy. The topline takeaway is that by 2017, GDP was 2.5% smaller due to the sanctions effect, but that the impact of oil prices on GDP outcomes was over over 3 times greater than that of sanctions. A pretty obvious distinction comes about from the author’s data showing the sanctioned banks/sectors that immediately began to deleverage foreign debt vs. those that, after an initial shock linked more to the oil price collapse and initial secondary sanctions risks from uncertainty over western policy, recovered. The following measures the level of change in foreign debt:

We can reasonably deduce that the outsized role of the oil sector in attracting flows of FDI and borrowing on international markets coupled with the specific banks exposed as lenders to the oil sector as well as state-owned defense firms exerted a much greater “gravity” on capital flows than the unsanctioned banks and sectors. It can’t be denied, however, that once Russian borrowers could only access foreign capital to service existing debts and couldn’t raise more money, the underlying logic of borrowing in Russia would change significantly — for instance, the relative cost of borrowing is much higher and, ironically, more bearable if the inflation rate is actually higher since that would inflate away the value being paid off, but higher inflation would naturally threaten the value of investments by accelerating their depreciation.

At the same time, we’ve seen from past newsletters and related reports and data points that the extractive sector’s net share of GDP actually grew after this capital shock because of its spillover effects across the economy. The loss of easy access to foreign capital markets prompted a logical shift in domestic political economy: sectors with the ability to access budget resources or lobby to generate regulatory rents such as the counter-sanctions regime for the agricultural sector benefited at the expense of Russian consumers and standards of living. The losses of earnings from oil prices were a more significant blow because they shocked the fiscal structure that had usefully propped up consumption and growth through various transfers while the financial sanctions created reputational risks that expanded from just the oil sector, where the decline in prices probably caused most of the loss of investment initially, only to then be choked off from easier foreign funding sources when prices recovered as they have (somewhat) since 2015-2016. You can see this dynamic reflected from HSE’s commentary on business just put out. The following smooths out any seasonality:

Light Blue = investment growth Solid Red = GDP growth Dark Blue = investment Empty Red = GDP

Net investment levels clearly track with oil prices more than anything, but in the absence of an external stimulus for investment such as an oil price rally, the only thing left for Moscow to rely on is domestic demand. That obviously never materialized as a growth driver because the state took a supply side approach to crisis management, I think with the political realization that supply side approaches were far more beneficial politically so long as they could maintain employment levels and reduce deficits. Consider then just how massive a shock in GDP terms for debt COVID has proven compared to the regime’s preferred debt levels and how little it’s done to shake confidence in Russian sovereign debt, the country’s fiscal stability, and how little an impact it’s actually had on inflation and other metrics traditionally cited by more monetarist-minded economics wonks and decision-makers with a friendly audience in Moscow:

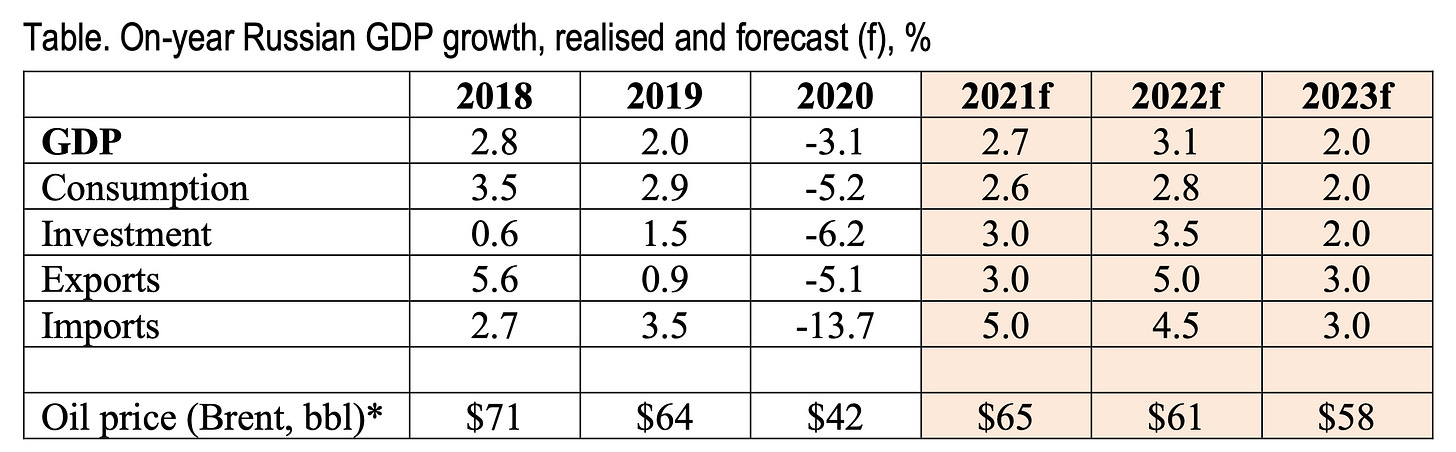

In the span of a year, net public debt rose roughly 8-9% vs. GDP without any evidence of macroeconomic instability and it wasn’t even spent effectively in supporting the economy. Imagine how different the growth arc for the country could have been had the Kremlin been comfortable with a net 20-25% debt to GDP ratio back in 2016-2017 just as the worst of the banking crisis had passed and the economy desperately needed a new stimulus for growth and investment. The sanctions regime, I believe, had the effect that it had not because the sanctions themselves, but because of how their perception as a policy problem reinforced the policy priors of those in Moscow who see the economy and the state’s finances as effectively inseparable, as though the existence of a budget deficit is a crime rather than a public good that can be used to invest in growth or redistribute resources. They brought the current political crisis on themselves. BOFIT’s growth forecast for Russia in the years ahead is, I think, slightly generous:

Forecasting is always fraught and their note is a great read, but the implicit takeaway is that external stimulus via higher oil prices feeds into the economy and lifts it more than expected. I disagree that higher prices will end up producing more growth, however, because higher prices will only be sustained by continued production cuts that hinder output and intermediate demand. Further, I’d expect prices to drop again, though their price forecast is probably close to where things will stand. But I’m curious about the leading indicators that consumption is only headed down this year. The decline in consumption of goods and services for 2020 hit 9% with the average Russian spending 20,200 fewer rubles ($277.90) in 2020 than in 2019. We’re witnessing the most belt-tightening in the Russian economy since the 1998 default. What’s more, the Central Bank’s financial flows review from February showed volatility for consumption trending hard downwards at the end of the month:

Title: Growth rate of inflows of payments into consumer sectors, w/o seasonality

Dark Blue = quarterly average Light Blue = 2020 Red = 2021

Things are supposed to be stabilizing, but the downward trend is almost as steep as the worst of April or July-August last year. It all comes down to exports. They could be resources like oil with higher prices short-term or resources with a longer elevated price runway (I still believe a commodity supercycle is coming, but it’ll be policy driven). Wheat will be interesting in this regard. Or they’ll be industrial exports the Russian economy is unable to consume domestically. The rise in oil revenues is estimated to be worth 2-2.5 trillion rubles ($27.5-34.4 billion) this year for the National Welfare Fund and, presumably, some disbursed social support. That increase in GDP will be pretty worthless if it doesn’t actually generate growth through investment. Sanctions aren’t the problem for the Russian economy, even though they have clearly had an impact. The problem has been developing adequate sources of growth and financing not dependent on external demand. HSE’s commentary reinforces this point when it lays out investment volumes in fixed capital vs. credit and profit levels. Green/Red is profit, Red/Green is flow of credit, Blue is investment, and Light Green is profit + credit flow in trillions of rubles:

We can see that while sanctions clearly takes out some of the credit available, the real problem is profits. These are in nominal terms, not real terms (so no devaluation adjustment), and we’ve also seen that producer price inflation often beats out consumer price inflation, yet those costs aren’t being passed onto consumers pre-COVID. Russian companies can’t make money without more effective demand. It’s that reality, not sanctions, doing the most to hold the economy back, and the real source of the crisis the Kremlin can now only control through arrests and intimidation.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).