Top of the Pops

I myself missed it, but earlier this week, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak threw his weight behind disclosure requirements for firms covering their exposure to climate change risks and, at the same time, the Federal Reserve has included climate change as a risk for financial stability for the first time ever in a quarterly stability report. The UK’s more directly interesting, as one would expect from the Task Force on Climate-Related Disclosures, some mechanism by which they measure their own impact as well. The. timeline for the requirements laid out was 5 years — plenty of time — and as of now, it only applies to firms with primary listings on the London Stock Exchange. But crucially, it’s likely these schemes are going to slowly be expanded to include firms that are cross-listed or otherwise using depository receipts to trade on multiple exchanges and tap more liquid financial markets. There are 35 Russian firms listed on the LSE, including VTB, Gazprom, Lukoil, Norilsk Nickel, Severstal, Sberbank, Gazprom Neft, and Novatek. The diffusion of financial reporting requirements is going to create a new body of publicly available material that lobbyists will grab hold of and governments will make use of in negotiations. Russia Inc. is going to be dragged, slowly, into this brave new world so long as it needs to access foreign financial markets in host countries pushing in this direction.

What’s going on?

GDP for 3Q was down 3.6% in year-on-year terms, less than half of the scale of the contraction shock witnessed in 2Q. When you consider that manufacturing was down 5%, extraction (led by oil & gas) was 11.5%, passenger turnover is down 44.7% and paid services are down 17.4%, the topline figure speaks to just how distorted the structure of the Russian economy is in relation to what creates value and growth. Agriculture was up a piddling 2.7% but export controls aimed at cutting off domestic inflation limit potential export earnings from what would is the second largest wheat crop no record in Russia. Despite outperforming Europe significantly, the division of national income does not suggest quite as rosy a picture.

Figures for January-September show that the budget deficit currently stands at 1.8 trillion rubles ($23.3 billion). Oil and gas revenues have accounted for less than a third of this year’s total, no doubt a spillover effect of prolonged lower prices. Domestic demand for debt issuances have supported MinFin through while foreign investors increasingly shun holding OFZs:

Russia’s fiscal consolidation looks to be in good shape overall, especially if the oil price rallies above $45 a barrel next year — an unlikely possibility, but worth considering. But the the loss of oil & gas revenues correlates to declines in spending and demand from the sector that transmit through other sectors still struggling to return to 2019 levels with consumer demand weakening.

Now that Mishustin has extended the tax holiday for small and medium-sized businesses till the end of the year, the pointyheads of Moscow realize that it’s just not enough. The holidays are meant to help the hardest industries — tourism, hospitality, sports, services most exposed to COVID. But it’s not actually addressing the underlying problem which is a lack of consumer demand and it’s just as likely that when firms suddenly owe those taxes, many will struggle to stay afloat. Boris Titov, the main point man for entrepreneurs and SMEs in the Kremlin’s policy circle, knows these policies resolve little. Now that suppressed demand from 2Q has already unwound itself in 3Q,

The FSB is apparently wielding its regulatory powers in the country’s Western Arctic to inspect fishing boats under suspected legal violations. It’s reportedly happened 32 times since the beginning of November and no one knows why it’s happening now. Legal changes over the right to treat and pack fish onboard vs. in port aside, the northern fishing basin accounts for a little over 10% of Russian fish production, with nearly 70% coming from the Far East. These interruptions and searches slow down deliveries, increase uncertainty, raise insurance costs, and also affect business planning such that they can slightly raise the marginal cost of fish bought in European Russia. If the practice spreads elsewhere because someone at the FSB has decided to wring money out of the sector, it’s going to contribute to inflation without any correlated growth.

COVID Status Report

Russia’s still breaking records with the latest daily caseload at 21,983 new infections. As we can see, all the variation continues to come out of Moscow with no evidence that any measures taken anywhere else are having any effect as of yet:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

It is estimated that nearly 75% of those infected have already recovered, but you have to wonder how bad things are when the spin machine decides that saying “look, they were sick but they’re fine now, right guys?” is the line you want to take. Tatiana Golikova is trying to wield her pulpit as Putin’s woman Friday on social matters to push for greater investment into rehabilitation and long-term care programs in general, and for those affected by COVID. That’ll be a tough sell to the budget hawks.

The Sick Man (is) Europe

Investors and financial managers still seem keen on selling a positive European story for life after the pandemic. Blackrock is advising its own clients that Europe’s growth trajectory, with adequate policy support, is strong:

This is obviously all conjecture, but it’s odd to hold that bullish a view when the policy environment, even with a Green Deal in the works, doesn’t hint at strong growth. The ECB is still going in circles about its inflation targets, a persistent punchline to a very, very boring joke told by a bureaucrat, and there’s the new possibility that some may propose the creation of a “bad bank” to absorb the non-performing loans held by other European banks that are now again on the rise with current wave of the pandemic. The ECB is chastising Europe’s banks for failing to adequately publish measures of their loan losses, sort of a fundamental piece of data you need to craft a policy response to COVID-19.

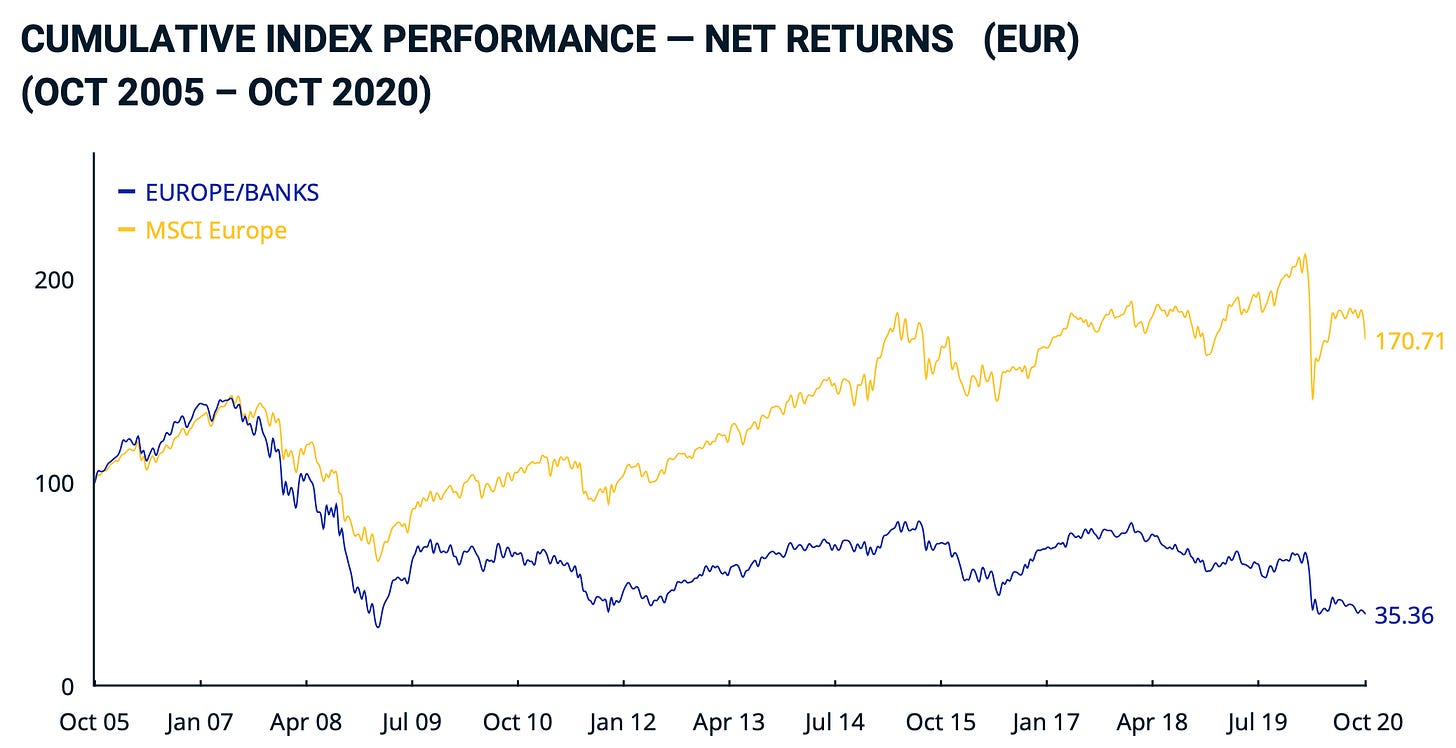

Compare now the equity performance of European banks against the rest of the world — led by US financial institutions:

The underperformance of the world index is entirely down to Europe’s miserly returns. US banks have been stealing a march on European ones when it comes to investment returns on their own markets. This is older data, but still useful from Bain:

In 2019, 4 of the top 7 dealers for fixed income financial instruments in Europe were US banks. No matter how much regulations advance, European banks have failed to turn adequate profits and have struggled with a lower rate environment than their US counterparts for a decade now who are steadily expanding their market share. That’s a huge consideration for future growth. Banks have reined in lending because of pandemic fears, but a new surge in defaults is going to feed into inadequate fiscal measures in a vicious cycle. From Bruegel, the US is still leading the way on immediate fiscal impulse by size (though that’s now run out and stimulus talks are gridlocked):

Every Euro that is not spent creating demand creates a knock-on effect vs. every loan defaulted, which creates a longer-run drag on growth as long as economies like Germany or France rely heavily on liquidity guarantees at a time when interest rates have to be held low to the detriment of banks’ interest earnings. Unemployment goes up, fiscal revenues go down, growth screeches to a halt. Despite having pulled off strong earnings for 2Q-3Q, weak bank profits and performance will then undermine future lending for growth. The situation is even scarier when you consider the looming wave of defaults, bankruptcies, and evictions in the US without further policy guidance and help from Congress and the Trump administration. The risk of financial contagion from securities going under, nothing like 2008 mind you, is still a big one and equity markets this year increasingly look like one giant trade with everyone betting up or down.

A weak European recovery is a problem for Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia because of how it fits into a big range of dominoes now falling in disorderly fashion. Weaker growth and bank sector weakness undermining recovery inevitably pose a negative drag on imports for EU-Russia trade. This from EU data (I know, I hate their bizarre obsession with using millions as the underlying unit too, but the EU is known for its efficiency):

Weaker domestic demand in the EU does not corresponding to wholly ‘accurate’ employment data as of yet for the simple reason that furloughs and state support to maintain jobs, crucial during the crisis, is going to have to end at some point. Whenever that point comes, there’ll be an initial period of turbulence for businesses. Going back to an earlier graph used in this newsletter, the falling income off of loans for banks eventually create a perverse incentive to raise rates to earn more, which then leads to more defaults and a worse outlook for demand:

So you’re looking at a weak demand environment on top of the demand dislocation from energy transition policies — obviously Russia’s primary exports to the EU are oil & gas. But the problem is yet worse because of the interlocking effects of European deflation vs. Russian deflation channeled via their currencies:

The problem here is one of competing deflations. The decline of domestic demand in Russia followed ruble devaluation triggered initially by an external demand shock and the collapse of oil & gas prices. But European deflation is partially a result of legacy impacts of internal devaluations by member economies of the Eurozone i.e. cutting costs, cutting spending, suppressing wages and related austerity measures. Since German exports drive the German economy and Eurozone’s current account, deflation of domestic demand can often correspond to relative appreciations of the currency which, in theory, would make it cheaper to import and consume more. But the underlying trends for EU-Russia trade show a steady creep up in European exports to Russian firms with downward pressure on Russia’s export surplus from falling prices. Since Eurozone deflation has pushed the Euro up in value, those exports are doubly threatened by Russia’s tepid economic policy response to the pandemic.

Banking sector weakness in Europe is also a long-term political risk for Russian firms that, as noted at the top today, may be exposed to policy changes for securities listings and foreign financial markets when it comes climate-related policies. The more market share US banks take up on European markets, the smaller the range of lenders Russian firms are going to have an “easy” time dealing with. Risk premiums are already bad since banks faced some uncertainty about potential future sanctions risks, but the growing strength of American banks on European markets slowly increases the influence of the US dollar and US regulatory power through the backdoor. Europe’s problems are Russia’s problems when it comes to recovery. Europe coughed first, Russia definitely got COVID.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).