COVID Status Report

First off, following up on an article currently in the works, I’ll be doing a post next week specifically covering how shale in the US is doing and how to think about where it fits into the recovery as well as future oil market.

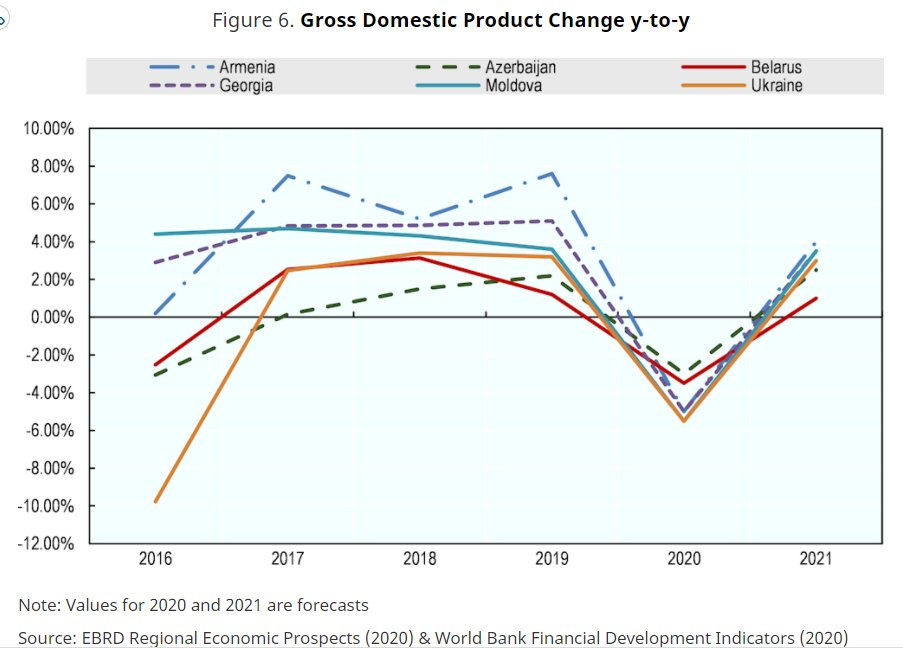

In case you missed it, worth taking a look at the OECD’s note from Oct. 16 on the Eastern Partnership countries, their responses to COVID-19, and recovery prospects:

Luka Way

Quick news hits for Belarus:

The US has denied Belarus market economy status while the European Parliament debates what comes next in typically indecisive fashion

The daily caseload for COVID-19 hit 619 yesterday, a figure to watch given that herd immunity requires vaccinations and other controls to work

Polish officials including president Andrzej Duda’s chief of staff Krzysztof Szczerski met with Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. She made a point of requesting employment rights for Belarusian refugees

Tens of thousands of protesters marched in Minsk on Monday despite the threat of live fire ammunition from the police. Today, Lukashenko ordered at a televised cabinet meeting that 73-year old Nina Baginskaya, a leading protest figure for the opposition over the last decade, not be arrested in a clear bone thrown to the opposition in faint hopes of easing the protests

Everyone knows that Lukashenko’s in a bind between maintaining power and maintaining Belarusian sovereignty write large. Between January and August alone, the nation’s sovereign debt increased by 29.1% to 57.8 billion rubles and other figures put the total at over $41 billion. Ongoing talks over debts owed to Gazprom, subsidized prices for oil and gas supply contracts, and more consume the state’s economic attention at the moment. The trouble began with Russia’s oil tax maneuver back in 2015 - raising feedstock costs for Russian refiners inevitably raised costs for Belarus to supply its refineries at Mazyr and Navapolatsk. Refined products (and oil and gas transit fees) generate the foreign currency earnings needed to keep the system afloat while making use of adjacent sectors such as potash production benefiting from energy and product input subsidies on top of lower labor costs. Add the oil crash in, the growth model is not only exhausted, but completely dependent on the next phase of Russian policy.

Watch the next weeks of talks with Gazprom as winter comes. Scanning public statements, it’s difficult to see just how much has been agreed and how much is both sides putting on a happy face, but clearly Lukashenka’s in a bind and can’t dictate terms.

Bish(kek), Please

The Central Electoral Commission of Kyrgyzstan has announced that the re-do parliamentary elections will go ahead on December 20, not the initial month timeframe that came out in the earlier stages of Sadyr Japarov’s takeover of the formal institutions of government. As Erica Marat notes, the other political prisoners freed along with Japarov - that includes former president Atambayev - have been returned to prison and the current struggle for power does not signal a change in political attitudes in Bishkek when it comes to its relationships with Russia, China, and the region. Unlike past changes of power, there is little evidence that the country’s opposition is united in its political aims aside from a desire to return to fairer, more pluralistic political competition of a kind seen earlier in the 2010s.

The worst of it comes from the visible influence of Raimbek Maitromov, an oligarch who’s made a fortune running trade terminals and smuggling and colluding with the country’s customs service as a deputy - always a classic in Central Asia - who was detained and then quickly released yesterday after agreeing to pay roughly $24.6 million in fines in what looks more like a campaign stunt for Japarov. The payment seems to many to act as reputation laundering. It speaks to a broader problem in the run-up to the election, both for the opposition and making sense of the country’s political landscape.

Russia retains considerable influence because of the country’s large migrant labor population, dependence on ruble-denominated remittances, and contacts with formal institutions, including the country’s membership in the Eurasian Economic Union. But private trade, especially smuggling, and private financial interests are increasingly dictated by China. Figures like Matraimov make a living on the shuttle trade China generates for Kyrgyzstan within the EAEU and with Uzbekistan, but aren’t “bought” by interested parties so much as rented depending on their own financial interests. Japarov is openly nationalist and well-positioned to use discontent with China as a political tool. While that’s not news in of itself, that’s going to be an important through-line since China provides many of the rents extracted from institutions like the Customs Service. Beijing has handled the crisis clumsily. They may regret that soon.

Sinews of War (and Peace)

I’m not in good position to make sense of the latest on the ground in Nagorno-Karabakh. Baku is adopting the time-honored strategy of fighting while you talk and talking while you fight, continuing to press whatever advantage it has to gain more territory back and more leverage at the negotiating table. Meetings in the US with Secretary of State Pompeo have little to do with resolving the conflict and everything to do with gaining more diplomatic legitimacy for other counterparts and for Pompeo’s own campaigning plans ahead of this US election and a likely run in 2024. At the moment, Azerbaijan appears to have the initiative, money, and the limits of Russia’s ability to interfere on territory that isn’t legally recognized as Armenia on its side. I’ve noted before that the conflict fits into a petrostate/resource wealth context, and I think it’s worth zooming out a bit to look at oil across the South Caucasus and Central Asia to see what it means for Baku. The following is taken from BP’s data (always handy) for a snapshot about the arc of oil production since 2000 by measuring annual changes in output against the average annual Brent oil price. I’ll come back to this chart another time when looking at oil’s future in Central Asia:

Almost all of Azerbaijan’s oil production gains came between 2005 and 2010, a result of business interests going back to the late 90s and an oil price cycle that was favorable. High prices from 2010 till 3Q 2014 failed to sustain output via higher investment, technological innovation, and most importantly, efficiency gains (high prices psychologically discourage firms to look for savings everywhere). Production’s only declined since 2010, which puts more pressure on the Central Bank and State Oil Fund to manage the currency’s value and budget deficits. Azerbaijan has not met any marginal increase in oil demand with its own production in a decade. However, Baku faces a shifting balance of pressures when it comes to maintaining its fiscal stability (World Bank data, so it’s probably not capturing everything. Site was glitchy today so I only managed to pull Azerbaijan’s data from it):

Servicing costs are undoubtedly far higher this year given the price crash, but the point is that Azerbaijan’s debt burden is increasingly geared towards long-term debts, rather than short-term debts (presumably the first things that would be collected). In other words, given the expansion of the country’s debts since oil production stopped increasing in 2010 and given the structure of repayments, they benefit more from acting now. For further reference, however, Azerbaijan’s nominal GDP for 2019 was in the realm of $47 billion. External debt stocks are worth around 33% of GDP. They can afford the costs of mobilization for awhile, especially if a nascent US stimulus deal comes together and the oil market gets a temporary lift headed into the winter doldrums.

Armenia’s in a world of hurt by comparison, both given its got one-third the population of Azerbaijan and its economy lacks a competitive export like oil or gas to drive growth, even if artificially and in a manner that is not sustainable. Pre-COVID, external debt stocks stood above $11 billion, over 13% of that was short-term debt, short-term debt servicing costs stood were equivalent to over 24% of export and primary income earnings, and GDP in current US$ was just over $13.6 billion. In other words, even small shifts in its current account pose systemic financial risks for its banks, businesses, and households. Similarly, Azerbaijan’s ample foreign currency reserves and earnings make it far easier to maintain its exchange rate peg, while the dram faces more downside risks which increase the cost of borrowing externally given that the domestic market is limited in how much debt it can absorb, especially since Armenia presents longer-term sovereign credit risks.

I’m not going to dive into the large losses of life because we don’t even have ready access to reliable reportage and figures and most of the analysis of any military gains entails guesswork, a degree in Google, and attempts to use stuff akin to PlanetLabs to take a stab at where the frontlines really are exactly. It is vital, however, to grapple with how high the economic stakes are for both parties and just how much better positioned Azerbaijan is to weather the economic fallout barring some massive Russian military and economic intervention. I can go deeper into the domestic political economy of both parties in a future post (probably not a newsletter), but suffice to say that Baku is going to keep grinding away and holding up talks unless facts on the ground change dramatically. The fact that BP has publicly sided with the Azeri government speaks to the reality that money talks when it comes to garnering diplomatic interest in resolving the conflict.

Ruble Tuesdays

Kazakhstan’s undoubtedly panicking from the latest oil market news. Though the 2020 budget was adjusted to assume an oil price of $20 a barrel, the folks in Nur-Sultan would breathe easier if Brent and, ideally, WTI stuck at or above $40 a barrel in tandem. The last few years, debt issuances have consistently outstripped state plans:

Title: In recent years, the government’s borrowing more than it plans

Black = plan, bln tenge Red = Amount actually borrowed, bln tenge

The novel development more recently is the Ministry of Finance’s decision to place 20 billion rubles’ worth of 3-year ruble-denominated bonds at an annual rate of 5.4%, 10 billion rubles’ worth of 7-year ruble-denominated bonds at an annual rate of 6.55%, and 10 billion rubles’ worth of 10-year ruble-denominated bonds at an annual rate of 7%. Aside from there being greater interest in subscriptions to the 3-year bond - understandably, investors wonder what whether it’s really worth holding a sovereign bond for a government dependent on the long-term oil price outlook - it’s an interesting development to see countries in Eurasia potentially turn towards the ruble as a means of managing their external debt loads coming out of the current crisis.

The groundwork for this specific issuance goes back to June when the Bank of Russia announced it was registering 14 planned issuances worth a combined 170 billion rubles from the government of Kazakhstan. The aim was to raise somewhere in the area of $933 million in external financing for the budget deficit. The logic is sound. The ruble’s far more correlated to the tenge than, say, Euros or US dollars so it’s safer from a currency risk perspective to deepen the country’s fiscal and financial exposure to the ruble.

Countries like Ukraine and Georgia are highly unlikely to want to go that route based on political preferences, and Azerbaijan’s commitment to a phantom peg against the US dollar and high dollarization of it current account will make it less likely to go that route. But Euro-denominated debt is now, in currency terms, more expensive since the Federal Reserve has out-eased the ECB and deflationary pressures in the Eurozone lead to its appreciation against the USD. It’s interesting to track regional responses against the broader problems facing emerging markets globally. This from Robin Brooks is a good reference:

While many emerging markets are now looking at dollarization to cope with COVID as investors don’t trust local currency bond markets in many cases, Russia’s fiscal discipline and continued interest from foreign investors - even if it’s declined in relative terms for non-residents’ share of OFZs purchases- may end up plugging some of that gap instead such that foreign investors would feel more comfortable holding bonds in Kazakhstan or elsewhere in rubles. Early days, but interesting to see that COVID might nudge Eurasia’s financial (re)integration. Given that the Belarusian ruble trades so much stronger against the dollar than the Russian ruble (thanks to Russian subsidies and the state controls), they might want to consider ruble bonds placed in Moscow, but then again, who knows how long they can keep their own ruble at current exchange levels…

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).