Oaf Wiedersehen

Renewables worsens Germany's nat gas price problem, but it doesn't have to be that way

Top of the Pops

Household finances have finally hit what appears to be a tipping point for purchasing power. Sberbank’s consumer activity index hit a post-February low on July 3-4. In June, net consumer spending began to fall. Below is the Sber index, what’s relevant are relative levels and not the absolute measurements:

Annualized inflation at the end of June hit a 5-year high at 6.4%. Since a big chunk of the consumption surge in 1-2Q was debt-financed, the question is how long does it take for falling consumption to rein in inflation? That’s unclear since domestic demand has relatively little bearing on commodity price levels globally. Agroholdings are screaming about price increases for fertilizer and are moving beyond calling for price stabilization and actually asking for price decreases. Now Mishustin is calling for measures to control the increase in prices for PCR tests for COVID instead of just taking the position that the state will organize and pay for them. Supply bottlenecks correspond to demand, and demand shifts in accordance with the health of household finances. But things like food and transport are a constant. Moscow’s about to pay a heavy price for returning the budget to surplus in 2022 at the expense of demand, capacity investment, and household solvency as the weakest SMEs and companies go under. Refinancing at lower rates last year provided a lifeline, one that required a counterpart fiscal policy in place.

What’s going on?

Something’s rotten in the state of Russian Railways. At a Federation Council hearing on the realization of RZhD’s long-term development plans through 2025, deputy general director Anton Zubikhin of Sinara Transport Machines (CTM) complained that in the last 6 months, the rail monopoly has stopped buying new track-laying and surveying rolling stock used to build and maintain railways and expand rail capacity. Sinara accounts for about 85% of all track-layer production capacity in Russia, and there isn’t any evidence some other supplier suddenly leapt forward. Sales in 2019 and 2020 were worth about 20 billion rubles ($269 million) annually, but RZhD’s stated needs for said rolling stock fell 85% in 2020-2021. The Institute for the Problems of Natural Monopolies found just 4.18 billion rubles ($64.69 million) of track-layers were sold for Jan.-May, a 51% decline year-on-year against 2021 and a 37.9% decline against 2019 levels. Without another 10 billion rubles ($134.6 million) in orders, CTM is going to have lay off 7,000 people — about 20% of its employees. Once they go, the relative costs of increasing production capacity and strain on existing output increase if demand were to rise again. But the spending plans laid out by Russian Railways cut track-layer purchases down to 8.6 billion rubles as a budget item per Infoline-analysts, significantly less than the 12 billion rubles the company claims it budgeted — both figures represent a drop from 2019-2020. What does this mean? Seems that less construction work is being done, whether due to price increases for materials, shortages of labor, or else attempts to crack down on corrupt waste given the problems the Baikal-Amur Mainline and Trans-Siberian works have faced. The problem’s bigger, though: the failure to use the COVID shock to push for a much larger investment program when the cost of state and corporate borrowing was lowest last year to correct for the shock and existing infrastructure and manufacturing bottlenecks is creating a structural drag on growth outside of households and consumer-facing industries. The loss of those jobs would be a big blow to Russia’s industrial capacity to maintain its existing rail network, let alone expand it, and that brittle supply/demand balance only gets worse the less they do for investment and demand. I expect some sort of intervention.

As the mortgage subsidy program has been extended, with a minor upwards rate adjustment, Russian banks have issued a record volume of mortgages for the first half of 2021. Big banks have collectively issued a whopping 2.21 trillion rubles ($29.85 billion) to Russians looking to buy property. Sberbank and VTB are clearly lead the pack, with overall issuances in the realm of 2.5 trillion rubles ($33.77 billion). Sber and VTB account for 72% of that. The following is in billions of rubles:

All told, it’s estimated that 500 billion rubles’ ($6.76 billion) worth of mortgages were issued in June. But this lending expansion is hitting up against the end of the bankruptcy moratorium and rising consumer indebtedness to pay for goods whose prices are rising all the time. 88,000 personal bankruptcies were declared for H1, an 110% increase year-on-year over 2020 data that showed a then 50% increase from 2019. Corporate bankruptcies are on the rise for the first time in 4 years — 9.2% to 4,920 cases total — as the moratorium has lifted and creditors surveyed showed a 30% increase in the intention to reclaim debts owed via legal proceedings. The more the banks issue these loans to prop up asset values for Russians as a salve for falling wages, the political tradeoff American authorities made with their housing push in decades prior, the greater the risk that rising costs of credit take out businesses and households alike whose creditworthiness keeps declining as Russians’ consumption falls. Financial fragility is a much greater problem after a debt-intensive recessionary shock whose mismanagement has led to economic scarring. June also saw record levels of cash loans — 622 billion rubles ($8.36 billion) for the month. Things aren’t looking great.

Forbes has some great scoops. The 100 wealthiest state officials and deputies got some nice raises in 2020 — they collectively earned 75.9 billion rubles ($1.02 billion), a 15.3% raise over 2019 while average real incomes declined about 3% for everyone else. The top 10 earners took home 43.7 billion rubles ($588.42 million) of that, 57.5% in total. Those top ten earners took home more money than the combined annual budgets of 13 Russian regions with a combined population of 6 million people. Chelyabinsk deputy and president of Yuzhuralzoloto Konstantin Strukov was #1 with a take home pay of 8.6 billion rubles ($115.9 million), a 66% raise over 2019. The head of Kamchatka krai, Igor’ Yevtushok, came in 2nd. The other details don’t matter a terrible amount. The deprivation imposed upon regional budgets isn’t just about political control — the Center can find other means to ensure complicity and compliance with important diktats and since everyone’s dirty, security services and anti-corruption investigations often do their job. Rather the problem is about efficacy. If Putin, others in the Kremlin, and across the government operate with an assumed overly hard constraint on state borrowing and spending, that doubles the pressure to crack down on excessive graft, which tends to be fueled by higher levels of state spending. But the lack of spending then empties out state capacities to govern over time and since property rights are politically contested and contingent, local businessmen, business, and security interests frequently enter politics to ensure their properties or businesses are safe, lobby for their friends, and prevent worse from the Center happening. As a result of these patronal systems, the incentives are greater to raise the pay of useful managers holding seats than to actually fund regional budgets adequately. And these figures in the regions aren’t saints of local government, they realize that state capture operates from below and middle out, not just from above.

VTB Kapital is warning that prices for coking coal — metallurgical coal used for steel-making — may rise 30-40% in 3Q because of the export targets that have continually been raised for the coal sector in recent years. It’s a double whammy for metallurgical firms in the making. Export duties intended to combat domestic price inflation for a range of metals take effect on August 1, but they don’t touch feedstock prices for domestic coal producers trying to seize the day since China’s banned Australian coal imports, raising prices globally and disrupting established trade flows. The result will be further increases in cost without the hope of realizing equivalent earnings from higher export prices and, more recently, the rise in the US dollar against other leading currencies. In the last month, FOB Australian hard coal prices have risen 22% to $181 per ton and CFR China coal contracts rose 12% to $303 a ton. Iron ore prices keep rising, too. Russkaya Stay’ estimates that current export tariffs will cost the sector about 150 billion rubles ($2.02 billion) in profits this year. VTB analysts suggest that domestic steel prices could fall 25-30% once the duties take effect, which is great news for Russia’s construction sector, decent news for housing prices, and politically mixed since it’ll encourage future interventions along similar lines. But the effects of the approach and the expected coal price rise will be uneven. Exporters can ride out lower domestic prices since they still earn decently abroad. If a firm relies entirely or mostly on Russian demand, however, that’ll end up squeezing their profits too. In economic terms, Moscow’s playing with differential capacity utilization — one sector of an economy running hot can mean another runs cold or faces problems. Rising tides do not necessarily, in fact, lift all boats, nor do falling tides beach them. The end result will be fewer profits to invest into production. China still holds a large excess of steel-making capacity that’s been supported by domestic over-investment, a combo that affects global supply/demand balances. Moscow’s living for today, not sectoral planning.

COVID Status Report

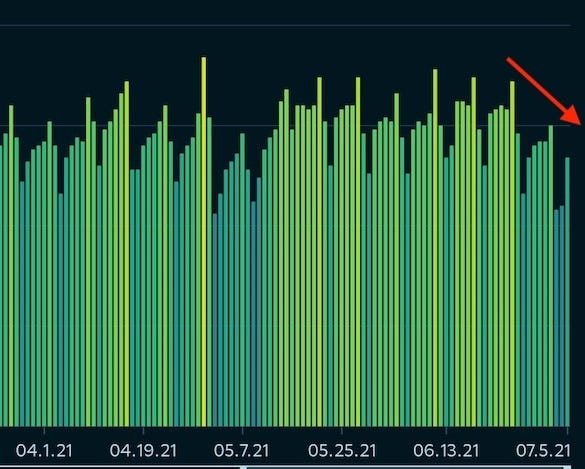

23,962 new cases and 725 deaths were recorded. The rate of increase seen across the regions is steeper than any prior wave (though testing is a part of that), worsened by the greater transmissibility of the Delta variant:

Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow Black = Moscow

Mishustin has ordered the Healthy Ministry to work up a vaccination model to achieve 80-90% collective immunity, which raises the question why the hell they hadn’t already discussed at least the possibility internally for modeling purposes? He’s also finally taken a public stand recommending that regions place restrictions on mass events. We don’t which ones, but health minister Mikhail Murashko confirmed yesterday that foreign firms had applied to register their vaccines in Russia and that foreign vaccines “will be sold.” Restrictions for businesses are going to have to expand across the regions. In Saratov oblast’, for instance, they’ve reported a marked increase in infections among people working in service jobs. That’s almost certainly happening elsewhere where steps haven’t been taken yet. Reapplying restrictions without a new business support package that goes beyond tax breaks or inspection exemptions is a recipe for further economic mayhem at the local level, especially in smaller cities and towns that can’t rely on national demand for services like Moscow or St. Petersburg. At the current rate, regional cases will match their second wave peak within a few weeks. So far, it seems fairly likely that the next peak will surpass the winter and possibly by a significant margin. Vaccine take-up may blunt some deaths and hospitalizations, but 20-30% would still be a far cry from enough given the risks the Delta variant poses.

Ties That Don’t Bind

One of the main recurring themes of energy transition and green development coverage and debates is the political economy of what I offhandedly think of as “disjointed” development. Often implicit rather than stated, it manifests in many ways. The most obvious challenge comes from the fact that surges of green investment in a developed market lead to higher commodity prices that pressure resource exporters to reap more of the windfall. Shifting lobbying interests from entrenched commercial blocs that have benefited from lower fossil fuel prices in developed markets tend to get less attention. The Daily Shot posted a useful graph today showing the long arc of German industrial output, and why the German export machine that has driven the Eurozone’s external balance of payments and internal politics faces some serious post-COVID headwinds with roots pre-dating the current crisis environment by several years. German industrial production has returned to pre-COVID trends, slowing down considerably in June. That’s a huge problem — and a potential opportunity:

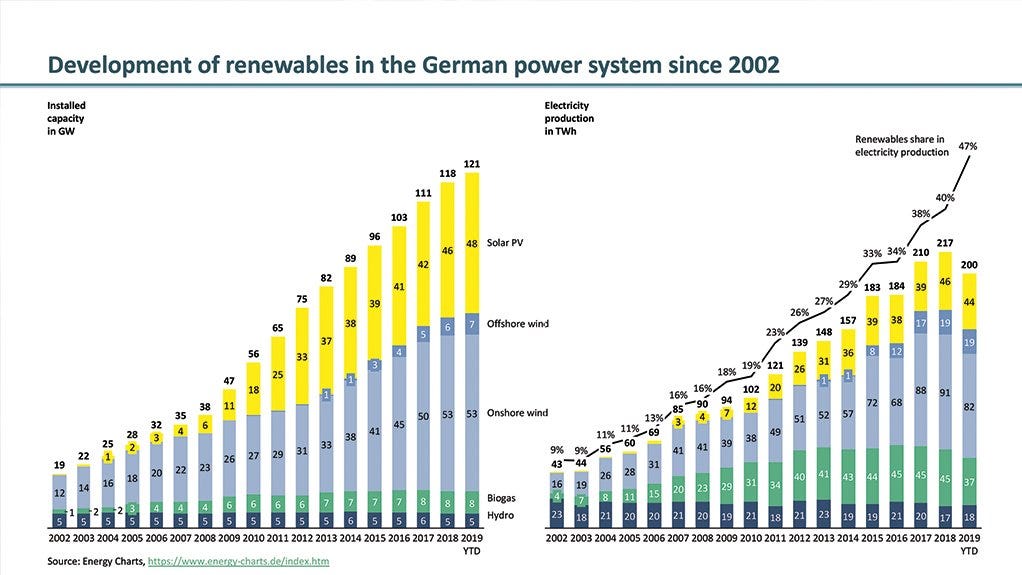

We can see the industrial output peaked in 2017-2018 and has since been on a steady decline. Some of that may be firms relocating production into China proper. Electric vehicle supply chains are also an important a headwind over time since EVs are mechanically simpler and therefore offer fewer component parts to manufacture and export. At the moment, supply chain bottlenecks biggest culprit whether they be difficulty booking containers or physical shortfalls of production for semiconductor parts and other electronic components. The trend, however, is there. Energy is a huge input cost for heavier industries and manufacturing since they’re energy-intensive ventures. The structure of costs matters a great deal. One of the biggest problems for Germany has been that natural gas continues to set the marginal wholesale price for power since it backstops whenever renewables can’t meet demand, so you get a case of “disjointed” development. The greater the share of renewables in the national energy, the more sensitive large consumers become in response to import price changes for natural gas. When you look at relative price levels for electricity over the last decade, you can see that price increases only start noticeably in mid to late 2017 and then pick up:

That coincides with renewable’s passing a threshold in terms of their net market share for power generation in Germany — that share rose from 33% in 2015 to 47% by 2019:

So we see Germany’s industrial production beginning to decline just as electricity prices start to rise, amplifying concerns about competitiveness. Think of it this way. German industrial manufacturers have been obsessed with securing low price, reliable natural gas supplies from Russia because the demand in Germany is there, they want to cap price increases since surcharges for renewables now account for 20ish% of consumer electricity rates — note that this balance is probably different for industrial consumers but still an important reference point — and German exports are the glue holding together the Eurozone’s balance of payments and internal flows of capital. Germany’s export surplus alone accounted for just over half of the Eurozone’s net surplus exports of goods and services in 2018-2019, and that was declining from 61.2% in 2014 just before the Eurozone fully stabilized. LHS is US$ blns:

Right now, European natural gas prices are breaking records and pricing and storage dynamics are setting up persistent high prices through winter. That intensifies the political pressure from German industry to lobby Berlin to go soft on Russia, and it’s also core to why the US backed off of killing Nord Stream 2. For all the howling about abandoning Ukraine, Germany’s export dependence and its centrality in locking the Eurozone into its persistent deflationary rut complicate the room for American policy to adjust. At the moment Gazprom’s ability to wield the ‘energy weapons’ has been defanged by antitrust action and market forces, there’s now a surge of concern about energy price inflation. This concern, however, is symptomatic of the conflicting timelines and vectors that affect the energy transition. Price pressures would ease relatively quickly if Germany availed itself of its considerable fiscal power to increase efficiency further, make more green investments, improve battery deployments and smart grids to best match supply with demand, support businesses, and reconsider its stance on nuclear power. The lesson is that what might appear to be resurgent Russian influence over energy markets in Europe and the ‘reactivation’ of one of its largest political and economic constituencies within the EU is about time horizons and decisions made in European capitals. In short, it’s a self-imposed problem, though no one should delude themselves that natural gas isn’t hugely important in the medium-term or irrelevant in market or political terms.

These disjunctures create paradoxical effects, doubling the extractive or political logic states like Russia have operated under and the price stability concerns consumers have had after decades of broadly low inflation outside of commodity price cycles. Like inflation, some of these disjunctures will be transitory and others not. Saudi Arabia isn’t going to be exporting tractors and leading frontier tech adoption. It’s going to be relying on its competitive advantages in oil & gas on a cost basis and its sunshine as fossil fuel demand enters decline. Russia’s in a more complicated position since its industrial exporters have long-standing ties to European industries now reexamining supply chains and their carbon and environmental externalities. Advances in one sector can undermine others domestically in Russia and other former Soviet states. There’s little hope at present Germany’s political establishment will break out of its ruinous economic consensus, which will lengthen the runway for Moscow’s ability to cultivate valuable business ties in Europe. The influence bought with molecules of natural gas, however, is waning. We now live in a world where fuel substitution is a much more meaningful threat to demand in the immediate term . High prices tend to cure high prices if they persist for too long. Democracies can eventually mobilize when the rents are too damn high.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).