Top of the Pops

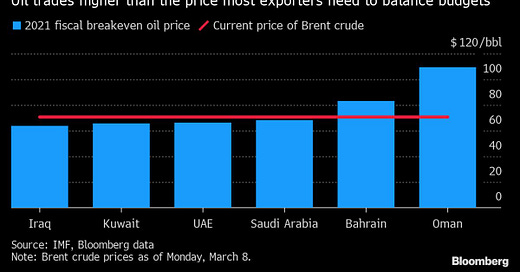

Oil prices rocked up past $70 a barrel on news of an attempted attack on facilities at the Saudi Aramco hub in Dhahran claimed by Houthis took place yesterday. It’s an abiding truth that the tighter the physical market for oil becomes, the greater the psychological shock to prices whenever a political disruption or event such as this takes place. Saudi Arabia is of course playing the victim and downplaying that it had been ramping up its bombing campaign with coalition support in recent weeks and immediately retaliated. The attack comes just days after the US Treasury announced it was sanctioning two leading Houthi commanders — Biden’s policy appears to be pulling back support for offensive operations (basically a lie/dodge for public consumption) while continuing to support Saudi operations logistically or else using sanctions instruments. But it’s unclear oil will stay higher for long on the news given past attacks and brief supply interruptions have faded quickly, even with the recent loss of 500,000 barrels per day of production from Canada. The current price levels are right where Saudi Arabia and most Gulf exporters want them for budgetary stability balanced against debt issuances and dollar pegs for currency management:

The oil market is still tightening with demand slowly clawing its way back. But there’s reason to believe that China’s slowing down new purchases because it stocked up when prices were low, which means that its actual demand is somewhat overestimated even accounting for traffic patterns and that the next stage of demand recovery probably has to come from the OECD, namely the US. The stimulus will surely help, we just know far less than the sleuths using traffic data or tracking tankers can actually tell us since they’re generally making massive assumptions that a) aren’t actually modeled b) are modeled badly c) can’t be modeled or d) project today’s behavior into the future without any dynamic feedback. All told, the $65 a barrel estimate for where the market ends up on the year is, I think, reasonable (though with some downside risks towards $60 a barrel remaining). Russia’s budget balances and industrial orders rise slightly, but the effect on the ruble will be muted as well as any potential lift for consumers. Banks, however, won’t have to worry about foreign currency reserve access again. If higher prices stick longer or else keep ticking up, however, the risks from US output will rise considerably.

What’s going on?

Friday evening, it broke that Rosatom energy storage subsidiary Renera bought a 49% stake of South Korean lithium-ion battery manufacturer Enertech International. The sum hasn’t been disclosed by Vedomosti — it’s generally safe to assume Russian SOEs overpay when it’s politically sensitive, but it’s not always the case. Finanz.ru reports that financial guarantees for the acquisition were worth $99 million with all guarantees operating under English law to last until July 1, 2026. Enertech is well established in the energy storage space, which is clearly the direction Rosatom wants to head to capture future market share and rents from battery deployment in Russia and, where it can compete, abroad. Localization of production and import substitution are the evident aims here and Rosatom is expected to sink 12-20 billion rubles ($160.6-267.7 million) into the plant with an expected annual production capacity of 2 GWh. The hope is to launch a new factory in Russia by 2025, the first of its kind making lithium-ion battery accumulators. Rosnano has the country’s only plant of its type, in operation since 2011 in Novosibirsk, with a few smaller producers on the market with negligibly small topline output capacity. Vygon Consulting expects the domestic market for accumulators to grow 30 fold (to a relatively lowly 2.6-4.6 GWh annually) by 2026 and Rosatom would have no direct competitors once the factory opens. It’s an important step for domestic manufacturing capabilities, though it’s 4-5 years away from launch, but if the market structure becomes monopolistic domestically and isn’t integrated into supply chains elsewhere, it’s most likely creating yet another sector whose demand and investment levels follow budget cycles without a broader growth stimulus across the economy in the years ahead.

The commission earnings on the Moscow Exchange grew a record 30.9% last year to 34.3 billion rubles ($459.1 million), accounting for a record 76% of all revenues in 4Q and 71% for the year. The breakdown for 2020 vs. 2019 is as follows:

The influx of retail trading and lower key rates are a boon for it, and I’m curious to see how the commissions play out this year since the rates won’t budge till late 4Q or early next year. It’s one thing to see the wealth effect have a greater impact on spending the more Russians decide to chuck some savings onto financial markets, another to see if the growth in commissions earnings continues and creates more of an incentive from brokers and the platforms benefiting from the retail investment surge to try and convince more people to hand over their cash. If inflationary pressures aren’t resolved — they well could just be a one-off as they are in most developed economies, but systemic underinvestment heightens the risk in Russia — then there’s more reason to take chances until deposit rates at banks are high enough to convince people their money’s collecting real value sitting in them.

Bank card issuance hit a seven-year record high during the pandemic, totaling 19.2 million credit and debit cards issued in one year per Central Bank data. That’s the most issued since 2014. There are now more than 300 million cards in total issued circulating around the Russian economy, 209.4 million of which are reportedly in active use. Active cards in use rose 6.9% last year vs. the implied 10.7% growth in total cards out there (the Central Bank allowed expired cards to be used during the worst of the crisis, which pent up some card demand). Based on a quick search for reference, base rates for consumer credit on credit cards seems to broadly be in the range of 19-21% — that’s 3-5% points higher than in the US, for some comparison. The fact that this expansion took place amid a pandemic with falling real incomes and limited measures to enforce compliance — it is certainly possible that fewer people wanted to use cash because of COVID, but payment tech was already there anyway — should caution anyone confident about recovery. Sustained improvements in business confidence require higher consumption levels and a growth in the use of credit to finance purchases is bad news without real income growth. Manufacturing doesn’t necessarily follow consumer demand as closely for its order logs. Extractives obviously don’t:

The Federal Tax Service (FNS) is launching a pilot project in collaboration with the labor ministry, the national Pension Fund, and Rosstat to better assess total income levels for households. The idea is to improve the data collected to calculate tax obligations and then pass it on to the Pension Fund, which hosts data on social support payments to citizens to improve the delivery of support at the right levels to the right people. 167 million rubles ($2.2 million) from the government’s reserve fund are being used to pay for it, building off of inter-agency experience targeting support payments from the initial COVID support measures. It’s hard to believe this isn’t a fiscal and a political measure disguised as optimization — people underreporting incomes due to informal sector activity are implicitly targeted and while there is most certainly a focus on improving the delivery of public services, social transfers already account for about a fifth of the national income. If that rises at all, it tends to benefit the regime by making stability more attractive (while also making inflation a bigger concern), but if they can reduce waste to target resources better, it also helps improve Russians’ experience of state social services. But it will help improve aid to those who need it most if it works, and it’s lazy to act as if there aren’t earnest interests in improving quality of life at play here. Yet again, it appears to be an attempt to institutionalize a measure built off of something undertaken during the worst of the COVID crisis last year, which would be yet another mark Mishustin is leaving on the across-government ability to cooperate and deliver (assuming it works).

COVID Status Report

New cases came in at 10,253 with reported deaths at 379. The rate of decline in daily cases has noticeably slowed and seems to be heading towards a new, much lower plateau, all the more likely as self-isolation regimes and other requirements — even if poorly followed — are being lifted in Moscow and elsewhere:

Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow Black = Moscow

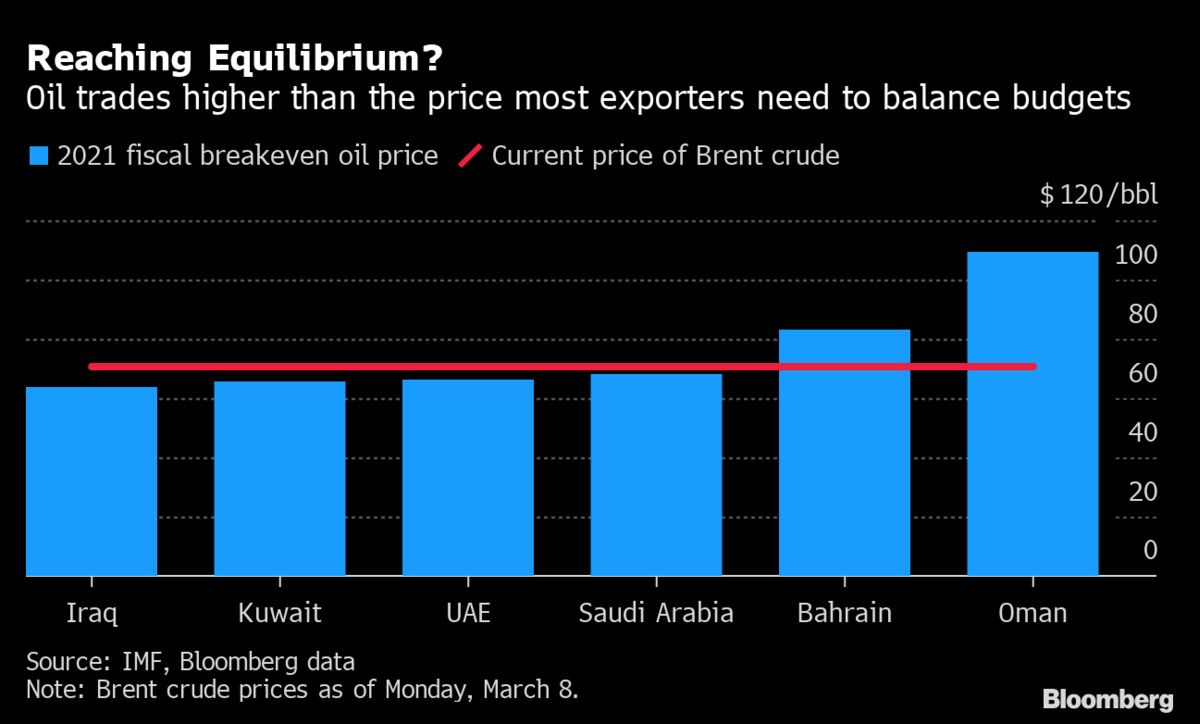

And as Moscow Times has noted, the data showed massive levels of excess mortality in January that, even with parallel decline, would still imply a much worse situation than these figures point to:

The argument that herd immunity has been achieved by natural infection rates holds merit to explain the decline, but it still understates the likelihood of people dying out of hospital or at home from how the virus interacts with underlying conditions or people getting sick and not reporting it or getting tested.

Time for No Huddle Offense

Carbon Brief’s late February post covering the expected net effect of current climate commitments is a good reminder that in most base cases without significant transfers of help and money from developed economies to developing economies, net reductions by 2030 will be relatively insignificant:

There’s no time to waste. The intended conference led by Biden for April 22 that should update nationally determined contributions (NDCs) for reductions will be really important to follow for marginal shifts in industrial and trade policy that will affect these targets. It’s amusing to see Tsargrad — far from the most quality of publications — attack Anatoly Chubais for calling on the national implementation of a carbon tax in Russia and citing KPMG’s work, which has been out there for months now. Per their editorial opinion, doing so would be ruinous for Russian industry and bring back the deindustrialization of the 1990s, artfully dodging that deindustrialization was also brought about because of the fixed exchange rate from 1994-1998 that made imports much more affordable on top of, you know, the disintegration of a fair part of the state amid mass disruptions to supply chains formerly located across the republics on a single market. But this is interesting to note because I think it demarcates where the political fight over decarbonization is going to take place: holding off on more radical measures can be defended as necessary to avoid the 90s, which is the raison d’être for much of the regime’s policy framework and existence, and business lobbies will follow this line.

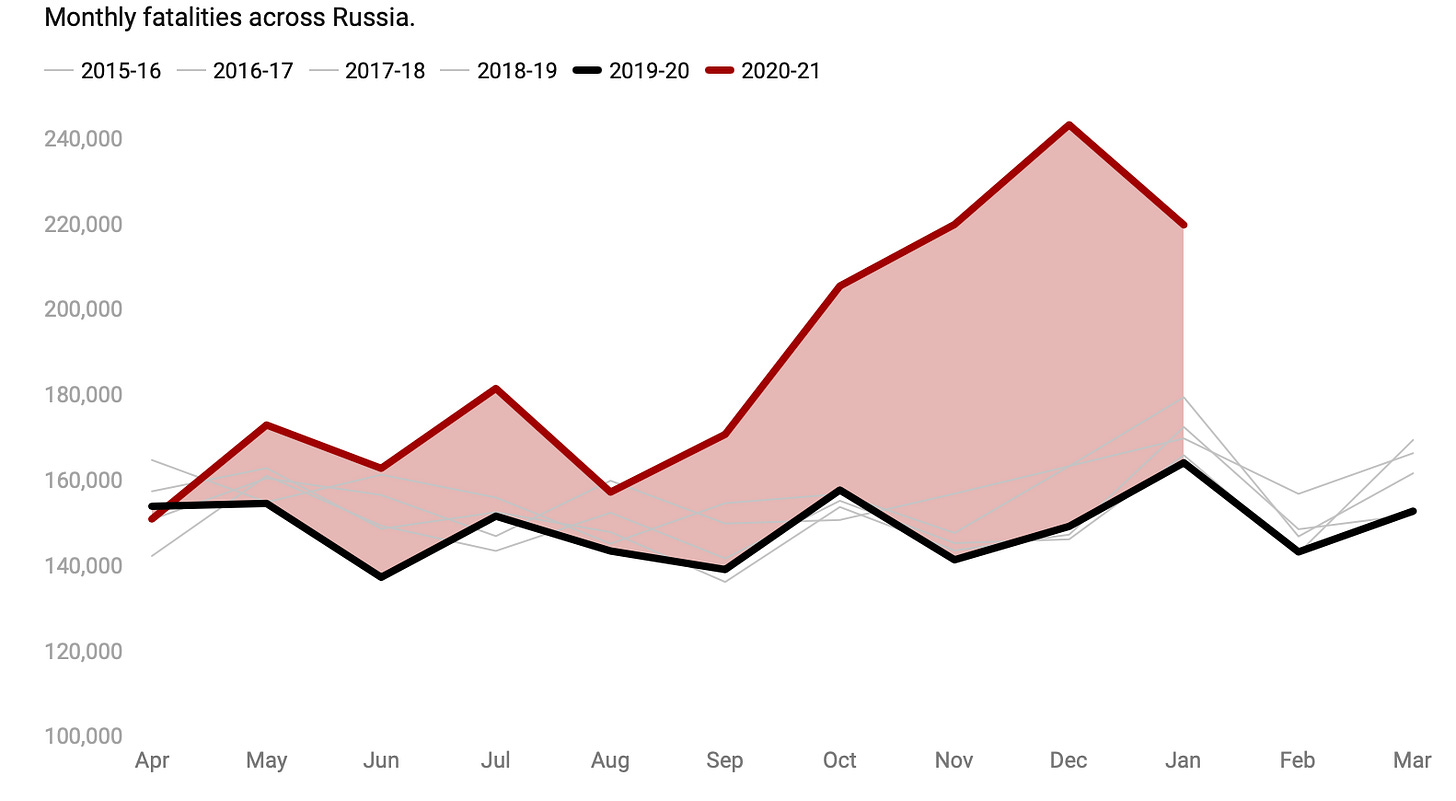

But there’s no longer space to ignore these changes by trying to insulate domestic policy choices and discourse from what’s happening abroad. Once trade partners impose a carbon tariff, for instance, what can Russia actually do in response? Retaliate over goods it has to import? In that case, it may give more domestic firms excuses to seek subsidies to localize production or else legally construct rents by distorting market competition, but you end up making Russians poorer because of marginally higher costs passed onto consumers either through higher prices or, in the case of many Russian policy interventions, through shortages. It’s just not something that can be spun into a siege mentality, especially since one of the main charges from policymakers and figures like Aleksandr Shirov representing the Russian Academy of Sciences is that the EU proposals thus far aren’t transparent enough. That may well be true of any initiative that has to be negotiated behind closed doors before going too public, but it means that the Kremlin has to engage with European governments on the matter. Berlin’s attempts to foster outreach and coordination with Moscow on the matter are aimed at the fact that for all the discord, Europe and Russia are still trade partners, still share a common neighborhood with differing security interests, and most importantly have a shared stake in addressing climate change since it’s a collective goods and action challenge. After all, Russia is the world’s 4th largest emitter (by country):

The current strategy to manage this tension is a bet on the cap and trade monitoring system being pioneered on Sakhalin. By monitoring emissions and creating a voluntary market offering financial incentives, Moscow can claim it’s acting while actually doing relatively little to threaten the competitiveness of its industries. Deputy Minister of Economic Development Ilya Torosov had a column out in Vedomosti about three weeks ago basically saying that working out an emissions reduction strategy and proper accounting system is an enormous undertaking (pat on the back, guys), that forest carbon sinks have to factor into the equation, that Russia’s already meeting its Paris Agreement obligations since emissions levels are effectively 70% what they were in 1990, and that more aggressive carbon taxation is a European plot to negate Russia’s advantages in energy so that production costs for things like steel and other energy intensive industries in Europe are equivalent with those in Russia. Thing is that Torosov is right. The carbon agenda in Europe is an explicitly protectionist one trying to generate a competitive advantage for European corporates that often can’t compete with American or Chinese firms (there are exceptions, of course). But Europe’s lost its first mover advantage with the passage of the stimulus bill in the US making way for a new infrastructure bill and diplomatic leadership from Biden that the EU has never been able to replicate. But complaining’s not competing. Torosov was laying out the negotiating position Moscow’s taking that mirrors the complacency of the cabinet in describing the safety of hydrocarbons’ role in the energy transition: we’re already doing our part as mandated multilaterally, what’s the deal?

The irony is rich. Moscow loves to claim multilateralism is the only means of solving a wide array of problems, inevitably in a manner that grants it a much greater stake in negotiating and problem-solving than its actual weight in global affairs outside of specific markets or measures of military influence and power are concerned. The Trump administration’s frequent fights for coal and against the energy transition were a boon for Russia because they disrupted said multilateralism on this matter. All the same, the absence of American leadership on the matter revealed what anyone paying attention to international affairs since the Iraq War and especially the Global Financial Crisis knew: Europe rarely can lead multilateral efforts effectively and requires a partner in the US. This is particularly true for this specific type of policy agenda since the EU is most certainly dressing up protectionism designed to re-shore jobs and bolster some efforts at greater economic sovereignty as a climate good. It is that, it’s just not the proximate casual political economy of how lobbying for anything like a systematic border carbon adjustment system works, especially given a decade of austerity, weak to nonexistent growth, and rising inequality. The celebrated American return to multilateral leadership has put Moscow on the back foot and now any net increase in emissions is a geopolitical tool, a trade tool, and a means of naming and shaming:

This is a corollary diplomatic problem for Russia. The US — and EU, though with a great deal more phony trepidation — will step up diplomatic efforts as well as domestic lobbying and policy rollouts from the Biden administration to use the energy transition as a rallying tool to get infrastructure bills and more passed. And since even China’s out front with an actual net zero target, Moscow can’t exactly rely on its relationship with Beijing as some sort of diplomatic shield. The narratives the regime has traditionally employed to protect industries and its own policy obstinacy won’t work for carbon taxation and climate change policies. Over half the country, per VTsIOM polling from September, thinks significant climate change is occurring:

It’s unlikely there’ll be a rally round the flag effect from ‘carbon nationalism’ in Russia, especially when so many Russians are concerned about their economic prospects and want better jobs that could be provided through green investment. The West isn’t the boogeyman for the country’s economic problems and the public knows it. All that’s left is for the regime to find some way of coopting expectations and muddling through.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).