Top of the Pops

President Putin, Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev, and Armenian prime minister Pashinyan met in Moscow yesterday to discuss post-conflict plans for Artsakh/Karabakh. The new working format between the three leaders will be used to lay out concrete plans for reconstruction and infrastructure (re)development across the region through the beginning of March given that the rump Artsakh that remains is now a territorial island and Azeris will undoubtedly seek to strengthen the transport corridor linking Nakhchivan. As of now, everyone seems content with the work Russian peacekeeping forces are doing, though undoubtedly some of that quiescence stems from COVID and a focused effort to head off any retaliations or provocative actions by returnees.

Karabakh featured prominently in the phone call Putin had with French president Macron just before Christmas, which reflects the extent to which Karabakh is the “new Syria” in diplomatic relations. Even though the EU had a minimal role to play ultimately, it’s become another ‘point of contact’ in diplomatic affairs with Europe, just as Syria broadened the strategic conversation from Donbas and Crimea in 2015. On that front, the EU is now trying to do the only thing it can do in these types of international affairs: win the peace after it avoided lifting a finger to do anything proactive in the resolution of the crisis. In this case, that means using negotiators and diplomats in support of the OSCE Minsk Group to try and establish a viable working format that doesn't involve Moscow. At this point, that’s farcical. Both sides have rejected such overtures so far for the simple reason that neither can afford to displease Moscow so long as Russian troops are delivering needed humanitarian supplies, maintaining access, and actually keeping the peace. The biggest challenge now is economic, and it’s something the EU is, whether it intends to or not, actually undermining with its current energy strategy, approach to recovery, and relative growth stagnation setting aside the political limits on FDI from the EU and other various barriers. It’s a bit janky (I used a secondary axis just to emphasize the divergence) but both Y-axes are %:

GDP growth is far too blunt to capture the intricacies of regional growth, but the broader point here is that Armenia and Azerbaijan live and die by trade, and are both highly exposed to the oil price cycle — Baku’s economy is dominated by the oil & gas sector (90%+ of export earnings) and the only major economy Armenia meaningfully trades with is Russia. Russia continues to suppress domestic demand, Baku has to carefully manage its fixed exchange rate, and Armenia lacks capital to invest into productive capacity and adequate physical connectivity and access to export markets. A green(er) recovery in the EU is only going to worsen these challenges and it’s too late to be of any use in resolving the conflict. Some might paint that as a ‘win’ for Russia, but really it’s a long-standing liability Russia now has to pay for at a time when it’s not delivering for its own people.

What’s going on?

The government has ok’d annual interest rate cuts for loans extended to small businesses in service of national goals from 8.5% to 7%. The policy will be paralleled by a round of rate cuts (read: loan subsidies) for construction firms building social infrastructure on state contracts to keep said annual rates under 3% to finance programs. This is particularly helpful for higher-cost construction projects in the regions. Though it’s being sold as a way of reducing debt burdens for companies, they’re really just shuffling around the financial exposure. Since the CBR risks a run on bank deposits if it cuts the key rate to match inflation — effectively rendering it a zero-rate for savers — so instead of broadly boosting economic activity by bringing future investment into the present, state policy has to offer what are effectively subsidies to banks to keep borrowing costs down. But unless the current account surplus recovers, the lower inflow of foreign currency into Russia creates (some) financial system risks that then encourage the suppression of domestic demand to accumulate more reserves. It’s a catch-22. It’s good short-run policy, but just as the mortgage subsidies have driven up housing price inflation, there’ll inevitably be limited distortionary impacts on investment that may not improve the realization of national goals.

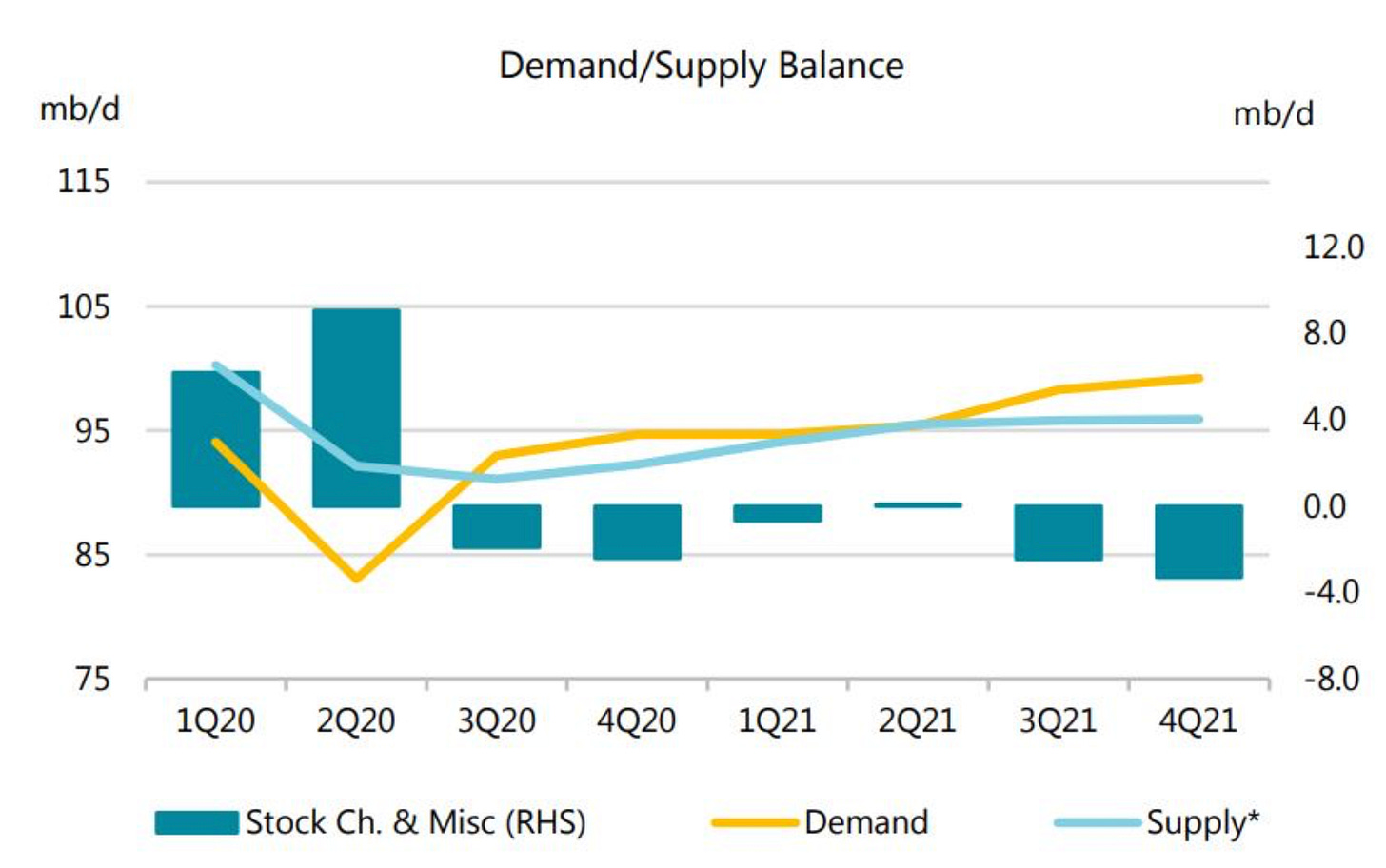

The oil price recovery seems likely to stall out over the next week or two. Large price increases led to profit taking on futures markets as traders cashed out, thus lowering the price back down again, but more importantly, the US dollar’s recent strengthening reminded market participants that oil prices don’t reflect supply/demand fundamentals at the moment. Russia’s losing out on a little revenue at the worst moment — the resumption of oil transited from Kazakhstan to Russia per a recent agreement has been halted due to extreme cold. Big picture, the reality of the new COVID strain has finally infected the market’s psychology, with more pronounced fears about safe havens for value — hence better US$ performance — and a dawning (re)realization that while vaccines offer a light at the end of the tunnel, demand problems are systemic, pronounced, and not going anywhere. The IEA’s mid-December estimates suggested it would take several months for vaccines’ real economy effect on oil demand to be felt:

I’m still waiting on Biden’s stimulus rollout. His backpedaling on student debt forgiveness and refusal to use an executive order to achieve it suggests his team, while thinking big, don’t understand just how large a drag on growth indebtedness creates on a job market that is not lifting wages and incomes for many people.

The Shopping Index for Moscow and St. Petersburg was down 24.6% year-on-year this holiday season, showing that the pandemic and weak income support policies continues to significantly depress foot-traffic with spending levels down 10-15%. Foot-traffic seems stalled at 85% pre-crisis levels, which is actually a terrifying thought when you consider that the newer COVID strain found in the UK carries much greater transmission risks for anyone standing in line for a longer period of time. Restaurant earnings were down 49% in both cities, a logical result of consumer fears of infection. The damage from forcing small businesses to open in place of extensive support and lockdowns may only be realized in the coming months if the newer strain(s) spread across the country. Consensus views hold that consumer activity will begin to recover in 2Q driven by the vaccine rollout. That makes a lot of sense, but it seems to presume there won’t be worse economic scarring if more transmissible strain(s) outpace the rate at which vaccines can be provided, especially if the presidential administration starts to curate the policy response to maintain sales agreements with foreign countries in search of geopolitical influence.

The Council of Energy Producers (CPE) is once again pressuring MinEnergo to change the rules pertaining to modernization programs for aging power stations so as to create separate modernization tenders for thermal plants from combined cycle gas units, increase the annual quota for power withdrawn from the grid from 4 to 6 GW, and to select projects that match expected total investment needs on a cost basis rather than cutting corners. The current investment program for 2022-2026 calls for 250 billion rubles ($3.37 billion) when the modernization program’s stated needs are three times that. In effect, the amount of modernization work that can take place has been capped to avoid short-run price increases (partially covered by subsidies/guaranteed payments to firms operating newer plants, partially by pricing flexibility). But as is always the case in Russia, attempts to control short-run prices create long-run investment imbalances and mismatches between supply and demand, thus creating a future inflationary pressure while also denying the economy much needed spending to generate more activity and growth. Companies like Uniper and Fortum are proposing MinEnergo adopt a more flexible approach for capacity write-downs instead of setting fixed values on a project-by-project basis and ending non-market controls on the volume of capacity available and costs. The lack of market signals is undermining investment into capacity, and poses risks for industrial power consumers in the longer-run as well. Nothing ever changes…

COVID Status Report

New cases finally dropped below 23,000 again though 531 deaths were recorded. While I’d like to be optimistic about the dip leading to more declines, the situation suggests otherwise:

Russian specialists actually see that the holiday period ended up blunting the spread of COVID and the presumed arrival of the UK variant because of how many people ended up effectively living in self-isolation regimes for a few weeks given how long the holidays run. That’s a very troubling indicator if it’s the case, worsened by the fact that the current figures aren’t quite accurate because the diagnostic centers weren’t staffed and operating at full capacity for the first 10 days of the New Year due to the holiday season. To some extent, we’re flying blind as to how the current set of protective measures are actually working with the newer strain(s) very likely to appear and spread across the country per expert views. Like the UK, it’s now a race to vaccinate as fast as possible. Sber has worked to develop a diagnostic too that would offer a COVID self-diagnosis within 60 seconds just using one’s voice and cough. The pressure’s on to innovate and act now.

War Pigs

In a largely pedestrian interview with TASS, Vladimir Mao of the presidential administration’s academic research wing (RANKhiGS) offered up a slow ball over the plate when assessing where exactly Russian policymakers’ head is at when it comes to the post-COVID recovery. The following are cobbled together across many paragraphs into a relatively concise point:

“Generally, we have an economy any country can be proud of. Few are the countries in the world, in which foreign currency debt — the most dangerous for the economy — was just 10-15% of GDP at the start of the pandemic like us. And during this, low inflation, a practically balanced budget, and low unemployment . . . [this crisis] isn’t economic or structural, it’s not connected to a liquidity crisis, it’s not cyclical, it’s external . . . in economic terms, this crisis isn’t connected to demand, it’s a crisis of supply . . . in these conditions, pouring money into the economy is quite dangerous because this crisis isn’t due to a lack of demand, but of supply. And supply doesn’t come from money.”

Mao goes on to clarify that this isn’t an economic crisis, but rather war with COVID, the mother of all external shocks. It’s truly astonishing to see so much economic and political economic illiteracy shoved into one interview with a quasi academic. imagine thinking that 4.9% net inflation — much higher for consumer staples thanks to the fruitless attempt to reap the benefits of agricultural exports without exposure to world prices that are rising because of demand pressures since consumers can’t spend as much on comfort and leisure and wholesale supply to restaurants has affected marginal prices for grocery stores — is somehow a pat on the back moment when real incomes have effectively fallen 6 years running. However, it speaks volumes about what Russian policymakers think is happening and how frighteningly unprepared they are for the post-crisis economic competition to come. COVID-19 isn’t a demand crisis? Irony is dead. Long live irony.

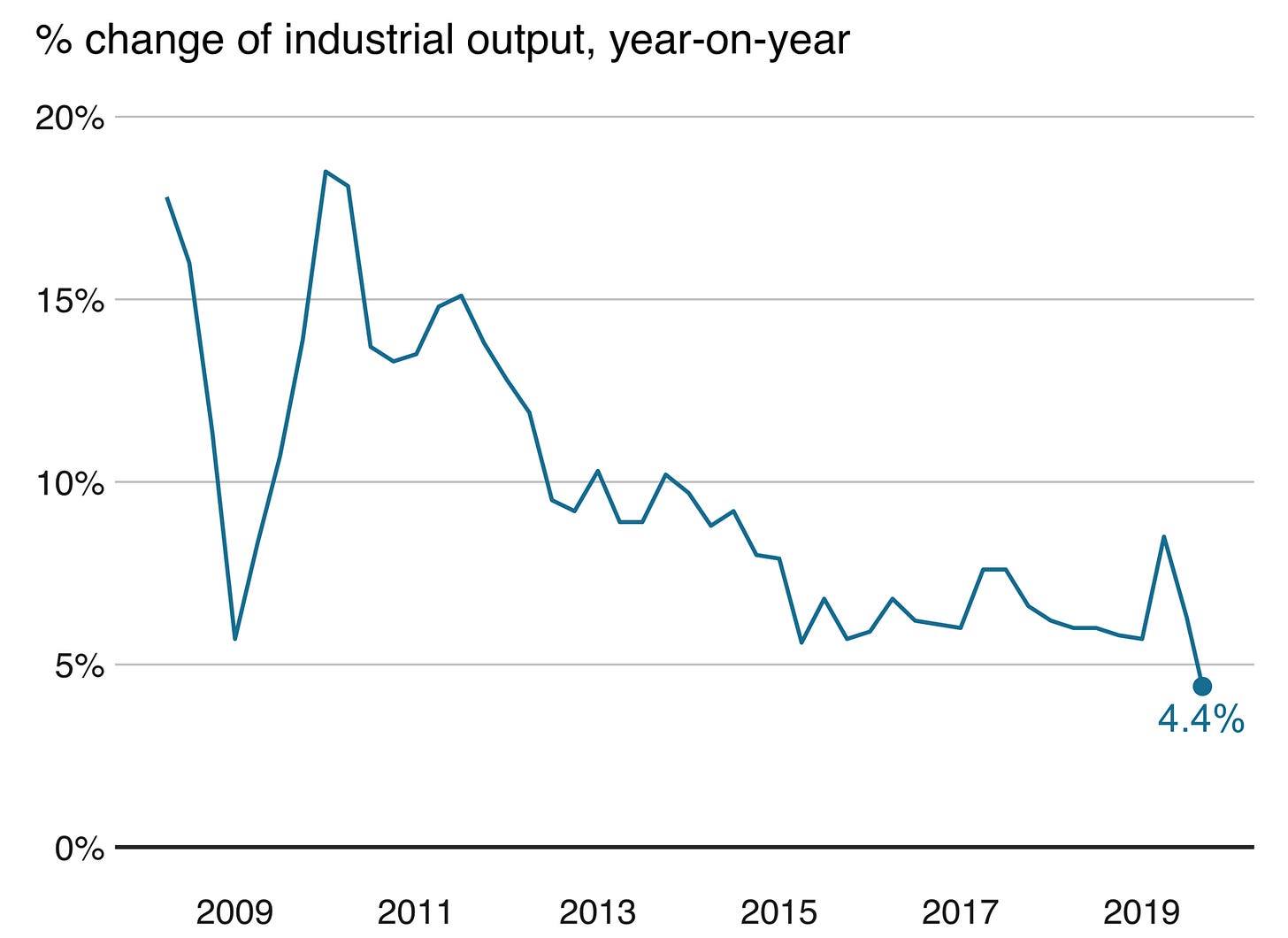

It’s important to note the structural factors pre-COVID that portended 2020 would be a rocky year economically, even if not quite the start of a global recession. Germany — the engine driving the Eurozone’s current account balance — had narrowly avoided two consecutive quarters of contraction twice in the 18 months prior to Jan. 2020 and, in usual style, refused to countenance demand side policies that would stimulate domestic consumption because of its preference to suppress domestic demand, run up huge export surpluses, keep wages lower, and free-ride off the Euro which increases German exporters’ relative competitiveness. Exports of goods and services (mostly manufactured goods) accounted for around 47% of GDP pre-crisis, and manufacturing PMIs weren’t looking great:

Below 50 indicates output contraction and as we can see, Germany was flirting with recession before COVID and services weren’t saving it. China was doing the heavy lifting keeping growth up — Germany’s growth correlates heavily with the Chinese economy, especially as German exporters have shifted to focus on selling to Chinese consumers. Then consider liquidity risks.

In mid-September 2019, the Federal Reserve began pumping tens of billions of dollars in liquidity weekly into the banking system to prevent repo rates — the cost at which banks could swap safe assets like US Treasuries as collateral to raise short-term cash to cover lending and trading operations, after which they buy back said assets at a slight markup — from spiking up due to a lack of liquidity. By mid-October, it reached a point of exceeding $80 billion weekly. This spills over into concerns about European economies as in the post-financial crisis world, investors desperately sought yield in a low interest rate regime. As the stock of debt borrowed at very low rates by corporates grew and grew, corporate loans began to be collateralized (CLO) to provide securities yielding returns, often on riskier loans, to investors:

Any significant slowdown in corporate earnings in Europe could lead to a spike of defaults, which would collapse the value of CLOs — this was a problem in the US as well, but European banks are woefully weaker and uncompetitive compared to their US peers. You can see how much stress CLOs faced in the early stages of the COVID crisis last year, though swift action by the Fed and European Central Bank stopped it from spinning out of control:

And all of that came alongside structural fears of a (further) slowdown in China as it runs a host of domestic financial risks in trying to transition to a consumer-led economy:

COVID simply accelerated all of these underlying problems and pathologies, worsened most by China’s supply side response. That doesn't mean we now face a liquidity crisis. But it does mean that to distinguish the COVID shock from structural weakness and problems that existed in both the real economy and financial system internationally is absurd. The saddest part of all of this is that the single biggest problem in balancing these various economic pressure points is the imbalanced distribution of demand globally due to domestic financial and trade policies in countries like Germany and China, as well as the constant suppression of demand in economies like Russia.

Mao tries to warn us about a potential ‘stagflation’ scenario and hones in on the oil shock of 1973 in the interview. Yet he seems to skip over that inflationary forces had spread internationally because of a combination of the inadequacy of the Bretton Woods system and idiosyncratic policy and economic forces in the United States that exported inflation to other developed economies. A combination of a growing dollar money supply without adequate gold reserves to maintain the price parity of a fixed exchange rate, wage inflation due to the effect of the draft on the US labor market, and an expansion of US deficits due to the Vietnam War and Great Society spending that had to be financed internationally by partners who had to import their dollars from the US (in a system with significant capital controls) triggered rising inflation before the oil shock and massive expansion of dollar-denominated borrowing internationally to finance imports of oil invoiced in US dollars. The expansion of the money supply has never been the lone factor in deciding inflationary forces, though it does play a role, particularly given that interest rates and other policy instruments affect where capital flows. None of these factors are at play at the moment. There are certainly risks of inflation due to much greater pressure on the supply chains we all consume from while stuck at home, or else from rising commodity prices now. But the underlying monetary regime underpinning this crisis has been in place for a decade. It’s now about fiscal spending, fiscal multipliers for growth, newer trade policies and R&D and so on that matter a great deal more. US banks, at least, are fairly well capitalized for this shock and European banks are, for now, ok. Chinese banks, well, the quality of the assets they hold are steadily deteriorating but I doubt Russian policymakers intend to criticize their partners in state capitalism.

The crisis for the Russian economy has been structural since 2013, and it’s, at heart, a demand crisis. The following is the current account balance once again, with the surplus as a % of Exports tracked on the RHS:

Growth begins to slow after 2010 and enters stagnation in 2013, when the country’s use of its oil earnings was financing a great deal of consumption domestically without actually creating productive economic activity that could sustain growth. Since then, the pressure on the current account has reflected the lack of non-oil & gas stimuli for domestic demand, a necessary means of actually undertaking economic diversification in the first place since newer Russian firms would struggle to competitively export on new market segments with new types of products initially. Demand drives investment which then generates supply. If the post-COVID economic regime in Russia is to take Milton Friedman as gospel and hop on the Ron Paul goldbug bus for good, then they have no clue what’s going to win the next stage of ‘multipolar’ economic competition. And just as Hyman Minsky noted, “all stable economies sow the seeds of their own destruction.” Economic stability (read: stagnation) in Russia and supply side mania are coupled with price controls and non-market mechanisms that doubly constrain investment because there is less demand to be met by it in the first place or else policy impediments to the realization of demand and the full use of the economy’s productive capital and resources. There are countless global economic problems with our current system and regimes, but we rightfully live in a demand-side world now. Hopefully Putin’s economists brush up on Keynes while they watch their geopolitical competitors outgrow them. Their Minsky moment won’t be a financial crisis. It’ll be a political one.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).