Top of the Pops

MinFin is preparing Russia’s financial sector for its full decoupling from LIBOR, part of a broader regulatory change in world’s offshore dollar system that’s largely only gotten traction with finance nerds for the last several years. LIBOR — the London interbank offered rate — has been estimated from British banks in London based on the cost of interbank borrowing for wholesale unsecured funds of dollars, but lacks transparency since it was an inferred value rather than based on observable data and will cease to operate come 2023. LIBOR-based funds underpinned as much as $300 trillion of dollar-denominated financial contracts — derivatives, bonds, loans, even credit cards. LIBOR and its continental cousin EURIBOR, the rate set for Euro borrowing between banks, can help gauge how de-dollarization efforts and moves to improve Russia’s monetary sovereignty are actually going. The Central Bank’s review of LIBOR operations within Russia shows they’ve steadily declined in volume, though LIBOR’s % share of non-fixed rate borrowing operations between banks has grown slightly (following in billions of dollars):

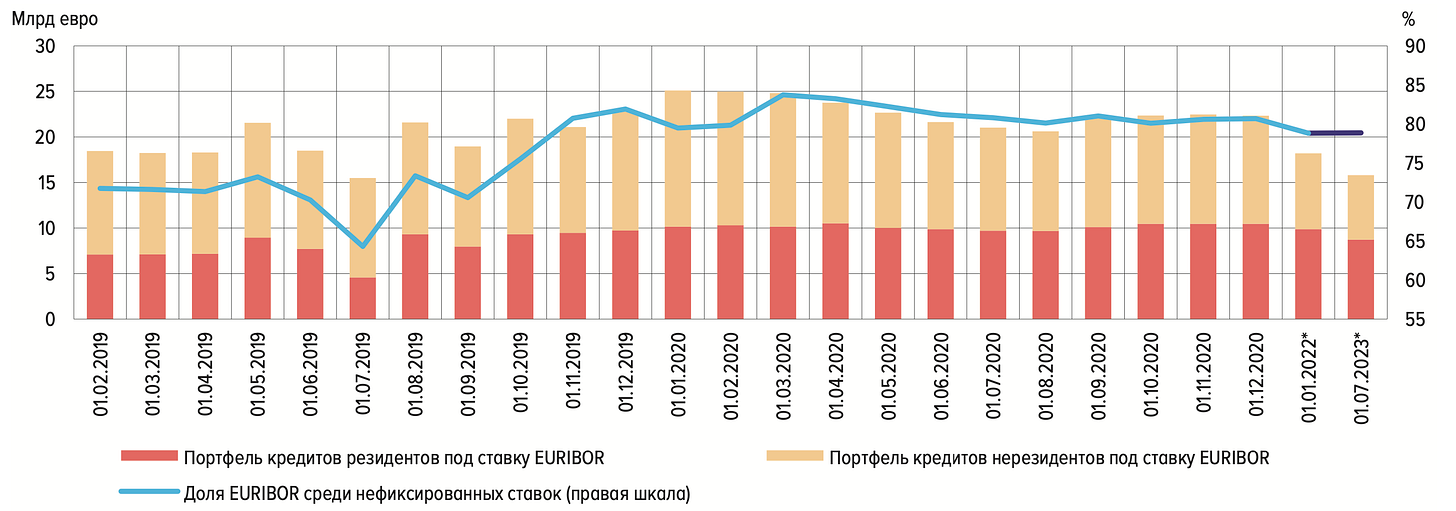

Red = portfolio of resident borrowing using LIBOR rate Beige = portfolio of nonresident credit borrowing using LIBOR Blue = % share of LIBOR in non-fixed rate transactions

The LIBOR volume largely converged with lending operations under the EURIBOR rate set by interbank operations in Europe, though the volume of EURIBOR borrowing now exceeds LIBOR in turnover turns significantly. Same color scheme but measured in Euros applying EURIBOR instead:

LIBOR and EURIBOR underwrote most everything together till the scramble to replace LIBOR — the LIBOR market was simply illiquid relative to the size of the global asset and liability pool priced using it — led to the initial rollout of the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) to replace it in October (in the US). The UK is rolling out its own SONIA while the Eurozone is going with Estr (Euro short-term rate). Switzerland and Japan have their own adjusted mechanisms as well. CBR data shows that LIBOR dominates open positions for currency swaps and that non-residents account for over half of the counter-agents in transactions using the dying benchmark while foreign bank subsidiaries take up a large chunk of EURIBOR transactions. It’s interesting to see no clear guidance forward yet emerge as to what should replace LIBOR, and the proposal now being worked up by MinFin and the CBR is intended to set a new unified interbank rate mechanism across all dollar, Euro, and ruble transactions. Risks for Russia’s financial markets are limited because it simply doesn’t take part in the types of leverage financial flows at scale that pose the massive systemic risks in highly financialized economies, but at the end of the day, Moscow can’t magic sovereignty into being when it comes to market trust. I’d expect they’ll end up following Eurozone practices more closely, but watch to see how China’s plans to adopt a depository-institutions repo rate of its own and how interbank rates in Shanghai and Hong Kong may influence policy rollouts as the more geopolitically inclined parts of the financial policy ecosystem mull the value of regulatory alignment away from the West. It covers a relatively small part of the Russian economy at present, but the scale of repo operations needs to rise if Mishustin’s policy drive cottons on to the reality that Russia needs a large financial market to finance investment needs if the state refuses to take matters into its own hands by spending more. That means ensuring adequate liquidity and, potentially, offering financial regulatory leadership within the EAEU to reduce the influence of foreign benchmarks on interbank borrowing between member states.

What’s going on?

Putin reportedly met with the heads of the Duma parties to discuss election plans and taking action against “enemies of Russia.” The latter point, reported by Vedomosti, speaks to how openly paranoid the siege mentality has become in a matter of weeks. Any collaboration between non-systemic and systemic parties is now off-limits. All of the stage managing precedes Putin’s coming announcement of a 500 billion ruble ($6.7 billion) social support package before the Federal government, a rather paltry sum that seems designed to make it appear as though the authorities are doing something rather than significant evidence of a change in orthodoxy. The economic impact of an additional $6.7 billion, presumably mainly spent by those without any savings amid an inflationary burst without resolving the underlying supply shortfalls/squeeze, will be quite small. They may intend for the support packages to be more targeted at helping out services as the economy recovers. Overall, though, the message said is one of panic and a search for the right band-aid, not systemic evolution to fix anything substantively. That could change, but the usual political tradeoff is to find a short-term fix that works while making the system more rigid and less able to react as needed to resolve socioeconomic problems. This seems closer to what’s happening now.

A new report out from the Center for Strategic Planning, MinEnergo’s analytical center, and the private '“Situation Center” argues that Russia needs to pro-actively develop new policy instruments to support market moves to roll out low-carbon and net-zero supply chains, energy sources, etc. They set relatively low estimates of annual losses for key exports worth about €1.6-2.9 billion annually through 2030. The following covers billions of tons of CO2 emitted:

Beige = shipping Purple = Japan Salmon = Russia Light Blue = India Gold = EU-27 Green = US Blue = China Gray = rest

The report proposes a cap and trade system that initially operates on a voluntary basis. That’s truly weak tea, but it speaks volumes that Chubais’ hobby horse of trying to internalize carbon externalities in economic activity is slowly catching on as the research infrastructure supporting public policy recognizes trouble ahead. Carbon adjustment just passed in committee in the European Parliament, an important early step in the painfully slow process of policy adoption in the EU. Mikhail Krutikhin, a major talking head and analyst of the Russian energy sector linked with RusEnergy and Carnegie, is now predicting that Russia won’t be a net exporter of oil by 2035 because of domestic costs, changing end demand, carbon policies, and the energy transition broadly. The internal consensus is changing, clearly. But it’s much more likely to encourage Moscow to soak the oil sector for all it can now than any attempt to decrease the equity and earning value of the sector.

The Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs is lobbying the presidential administration against a proposal to create a centralized federal data platform for automobiles that would be used for future work on self-driving cares, optimizing traffic flows, as well as by insurance companies and others who could commercialize its applications as proposed in a new law. The RUIE cites concerns about personal data protection and, more importantly, the business case against a public data pool. If everyone’s using a public data store that requires X technical improvements to the existing car fleet, there’s little incentive for any one firm to improve its data collection or otherwise invest into the intellectual property needed to make best use of said data because they forego a crucial part of the business — the sale of user data to other sectors and firms, which can offset high initial costs and loss-making activities during an initial rollout of new tech as well as advantages gained by having better, more refined data in-house. By forcing companies to hand over their data, they create a massive risk for competition, especially since federal money will be subsidizing localization initiatives that will support the rollout of newer, smarter cars. If the approach in Russia ends up being to create new federally-owned ‘distribution centers’ for data in different sectors, it’ll be a fascinating policy area to track to make sense of how securitization and the provision of data as a quasi-public good affect Russia’s tech ecosystem during a period of what’ll likely be rapid change and higher levels of investment into innovation globally.

MinStroi is extending its national housing program launched under the 2018 national goal plan targets another 5 years so that it runs through 2030, increasing the total expenditure outlay from 2.4 trillion rubles to 5 trillion rubles ($32.47 to $67.65 billion). But the net construction outlaid for 2021-2022 actually shows decline before construction starts picking up more in 2023. The next two years, the ministry expects to build less in 2021 than in 2020 by a few million sq. meters (a decline of 80.6 to 78 million) and then rises to 85 million sq. meters in 2023. The program had to be expanded in response to the reality that real incomes continue to decline, which makes housing a bigger part of consumer spending and also makes the current burst of price inflation for new builds a concern for the national program if prices don’t fall enough. MinStroi’s initiative may well fall prey to the influence of global price inflation for construction as green retrofits, infrastructure plans outside of China, and attempts to expand green energy’s share of energy mixes lifts demand for steel and other commodity inputs. The slowdown the next few years, however, might also create more pressure on the housing market for those who can’t afford to take out mortgages to buy under the subsidy schema, but I need more refined data and better data to look at before making any larger leaps.

COVID Status Report

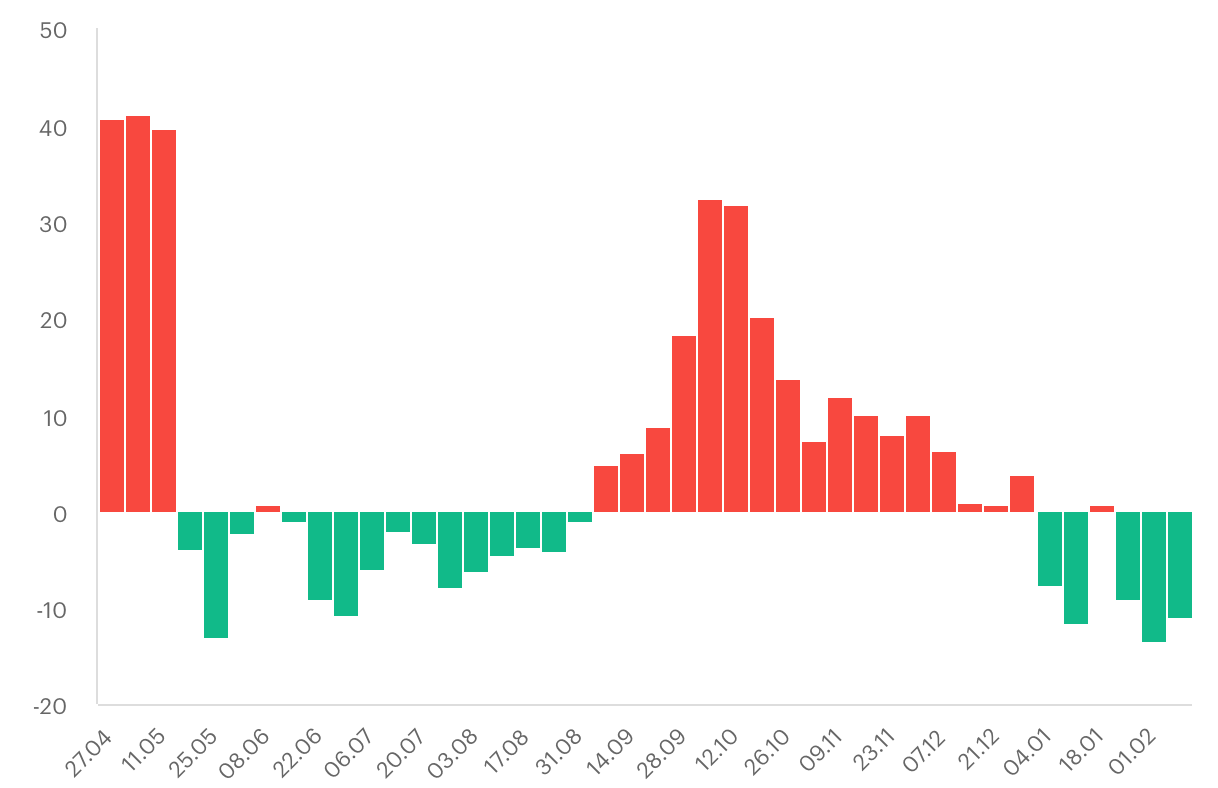

Daily cases fell to 15,019 while recorded deaths rose to 530. The Operational Staff data shows a continued strong % decline in cases on a weekly basis, with the last week-on-week caseload growth rate coming in at -10.8%:

Yandex search data related to COVID shows that while the federal data almost certainly understates the real situation, it’s not that far off. The bigger issue is that the search data in early February shows that the rate of decline for cased has slowed considerably, which would be an effect of the vaccine rollout and psychological easing of observance of things like social distancing, while the official data shows continued decline. Rospotrebnadzor is making sure to message that while the decline is happening, it’s too early to ease up on restrictions. Given that Moscow is now trying to register Sputnik-V with the EU to open up vaccine exports, the official data seems closer to reality than it was, say, two months ago despite the massive gaps in mortality statistics as reported by Rosstat. The real trouble comes when people realize that reopening won’t actually help incomes that much given the years preceding the COVID shock.

Ships of State

I’m struck by Mikhail Krutikhin’s warning that Russia won’t be an oil exporter by 2035 mentioned earlier, not just for how firm his conviction in the prognosis is, but also because of how overblown Russia’s escape from oil dependency has been. In particular, Krutikhin put his finger on the problems created by the oil tax maneuver that started in 2015 and was ostensibly a means of (slightly) reducing budget revenues’ price exposure. Regarding swapping out the export duties for higher MET:

“Any new [upstream] project will only start to generate cash flow after a minimum 7 years — that’s an optimistic scenario. As a rule, [more like] 10-15 years. And who knows what the taxes will be in 10 years? One time Lukoil counted 22 changes to tax terms in 3 three years.”

Oil sector taxation was the original fiscal backbone that allowed Putin’s regime to consolidate because its luck. Highly progressive taxes imposed on projects and exports as oil prices rose passed in 2001 when the price expectations for the decade didn't top $35-40 a barrel before spiking as demand grew faster than supply could keep up thanks to an acute investment shortfall isn 2005. It’s been short-termist ever since, along with macro policies managing the downsides of oil dependence such as Russia’s own version of Dutch Disease — shrinking export complexity, growth of imports financed through oil export revenues displacing domestic production, the sector’s role in generating intermediate demand and business cycles and cross-subsidies, and fiscal dependence. The two most common metrics to make the claim that Russia’s lessened its oil dependence are in net revenue terms for the consolidated budget, thanks in significant part to the 2017 budget rule, and the (relative) decoupling of the ruble from the oil price. Both merit (re)consideration for the year ahead given the growing pressure on social and fiscal policy to support what could well be a rocky campaign season. Navalny’s team has ordered a Valentine’s Day protest nationwide, but mostly as a means of testing their ability to mobilize turnout rather than provoking any conflict with authorities.

Meduza’s writeup (English) on the budget rule is a good glimpse of the problem: whenever oil’s at or less than $42.40 a barrel, 100% of the revenues cover budget spending obligations. Once they’re higher than $42.40 a barrel, all the extra revenues are “sterilized” by being parked in the National Wealth Fund. This heads off inflationary pressure, reduces the effect that higher oil prices have on the ruble (pushing it up), and creates more fiscal space to absorb external or internal economic shocks. But the budget rule wasn’t a means of ending oil dependence. It was an austerity measure that was part of a relative pullback in spending as seen here. Spending levels kept rising in absolute ruble terms, but the 2014-2015 devaluation and economic shock doesn’t significantly change the trajectory from 2006 as you’d expect:

By looking at the cumulative surplus and deficit pre-COVID for what’s identified as oil & gas vs. non-oil & gas per their accounting identities, the increase in non-oil & gas revenues, while substantial and even better improved during 2020 due to the effects of low prices, corresponds to significant transfers rooted in the performance of the energy sector. That trend actually accelerates after the adoption of the rule since oil prices rose, but because the additional revenues were parked into the National Welfare Fund and not spent, they failed to generate spillover economic activity that might have further boosted non-oil & gas revenues and instead went towards assuring international investors about Russia’s finances and, within bounds, stabilizing the ruble by ensuring domestic access to foreign currency. The budget rule was also meant to help keep the ruble weaker, which would boost oil firms’ relative profits — they sell in dollars and Euros, spend domestically in rubles — while theoretically making non-oil & gas exports more competitive. The latter never happened because oil rents were redistributed to protected domestic industries instead of exporters who were allowed to fail against foreign competition (and each other).

The ruble ceased to be positively correlated to oil prices significantly as budget rules and currency management practices in terms of operations to buy and sell foreign reserves changed — when prices rose, the ruble wouldn’t increase by much in value — but negative oil shocks immediately feed into the ruble since they harm so much of Russia’s real economy. In other words, Russian macro found a way to insulate itself against the risks of exchange rate appreciation (and therefore some sources of inflation) but remained exposed to most of oil’s downsides since the money parked aside isn’t spent on much to materially reduce the economy’s dependence on the sector. Krutikhin’s comment nails this problem, even if it’s not explicitly speaking to it. The amount of uncertainty generated by the fiscal policy changes needed for Russia to maintain austerity policies render long-term investment planning for the national cash cow extremely difficult without state guarantees and support. This helps explain why Vostok Oil is so salient not just for Rosneft, but the entire sector. Only a company like Rosneft could reasonably expect to extract guarantees to justify that type of investment with the decade needed to cover costs of initial investment, never mind ongoing capex and opex as oil prices fluctuate.

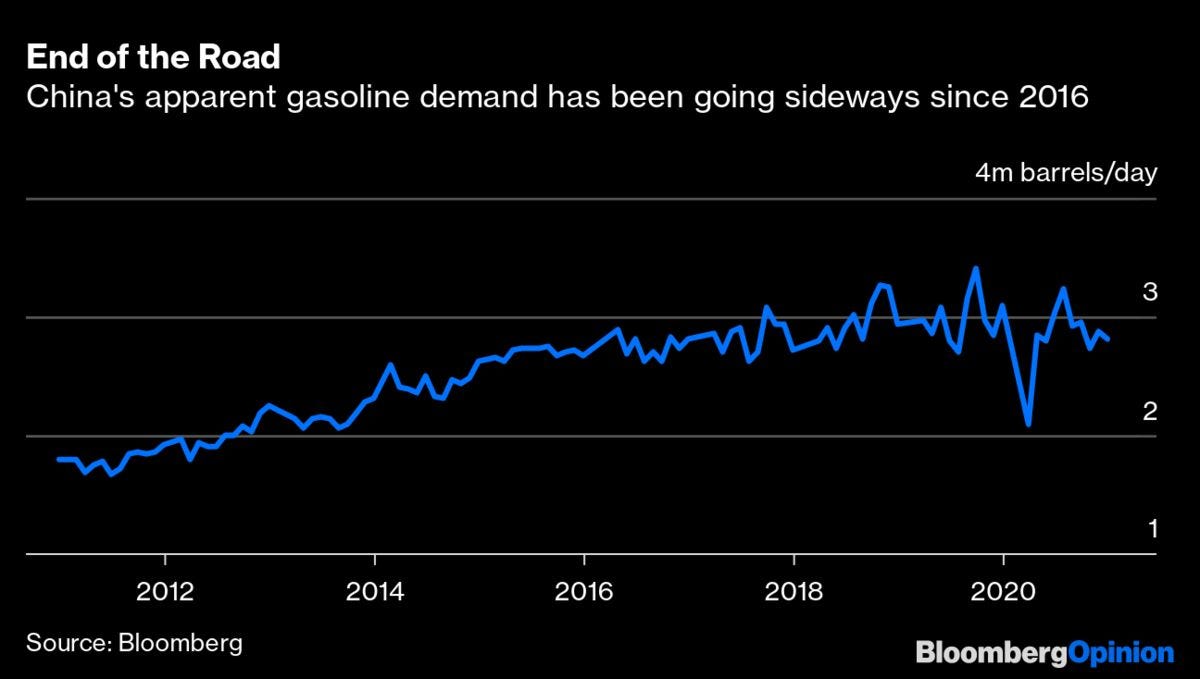

I tried to find the original source and couldn’t pull it, but it’s worth remembering Mohammed bin Salman’s brief attack on Russia in an interview (I think with Bloomberg) back in 2018-2019 when he claimed that Russian oil would leave the market in 10-15 years. The Saudis recognize the crude reality of the position Russia’s in compared to them. There is no means of creating spare capacity in Russia. It’s simply too expensive, the fiscal environment is a mess, and relative production costs are rising continuously. Krutikhin mentioned in his interview that there’s little hope of the creation of a national strategic oil reserve that would allow the state to buy volumes and resell them at convenient times. Creating such a system would be inefficient and lead to even more intra-sector problems. It’s exceedingly difficult to make meaningful forecasts. But Krutikhin’s warning is well taken and, I think, serious when you look at the economics of maintaining market share once demand enters decline as it costs the state in Russia more and more to maintain the oil sector, and thus stabilize the ruble via export earnings, at the expense of its fiscal framework (which has failed to finance adequate diversification). Consider China’s gasoline demand has been stagnant structurally since 2016:

In other words, more of China’s demand growth has come out of plastics, product exports, and other refined product consumption separate from road fuels, which are the leading edge of demand decline (even once jet fuel levels return to normalcy). Russia’s oil dependence has not diminished or ended, it’s been transformed via an increasingly complex system of austerity fiscal instruments meant to prevent inflation and the emergent political economy of business lobbies in Russia that benefit from a weaker ruble, namely the oil sector itself. The shifting fiscal load onto non-oil & gas revenues is happening, and crucial for the regime’s survival in the next decade. But as export levels drop, the question is what the next short-termist bargain looks like. Increasing the tax burden on the sector as prices rise is generally the first impulse of the state so it can hoard money for later not-use. But any increase in the tax burden worsens the problem of redistributing federal money back into the oil sector to maintain output because of rising investment and production costs at the same time Russia’s largest competitors — mostly Saudi Aramco, but also US shale and newer offshore finds — are adjusting their strategies to the new market accordingly. Russian oil & gas stocks have outperformed their peers since COVID hit:

Without a jolt from the state, like a new approach to carbon policy, they don’t have a business case for why they should change their way of doing things even with all the uncertainty and inefficiency they face and generate through their own business practices domestically. A growing, if disempowered, chorus in Russia realize this.

The politics of the oil market and OPEC+ can only get uglier from here. As Logan Roy in Succession teaches us, you best come correct when you aim for a king who’s “in the middle of turning a ****ing tanker.” The question is who’s the king. What was once spun as a resounding political victory for the Kremlin in the Middle East became supplication last year with no end in sight. The market’s on Mohammed bin Salman’s side. That should worry us all.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).