Top of the Pops

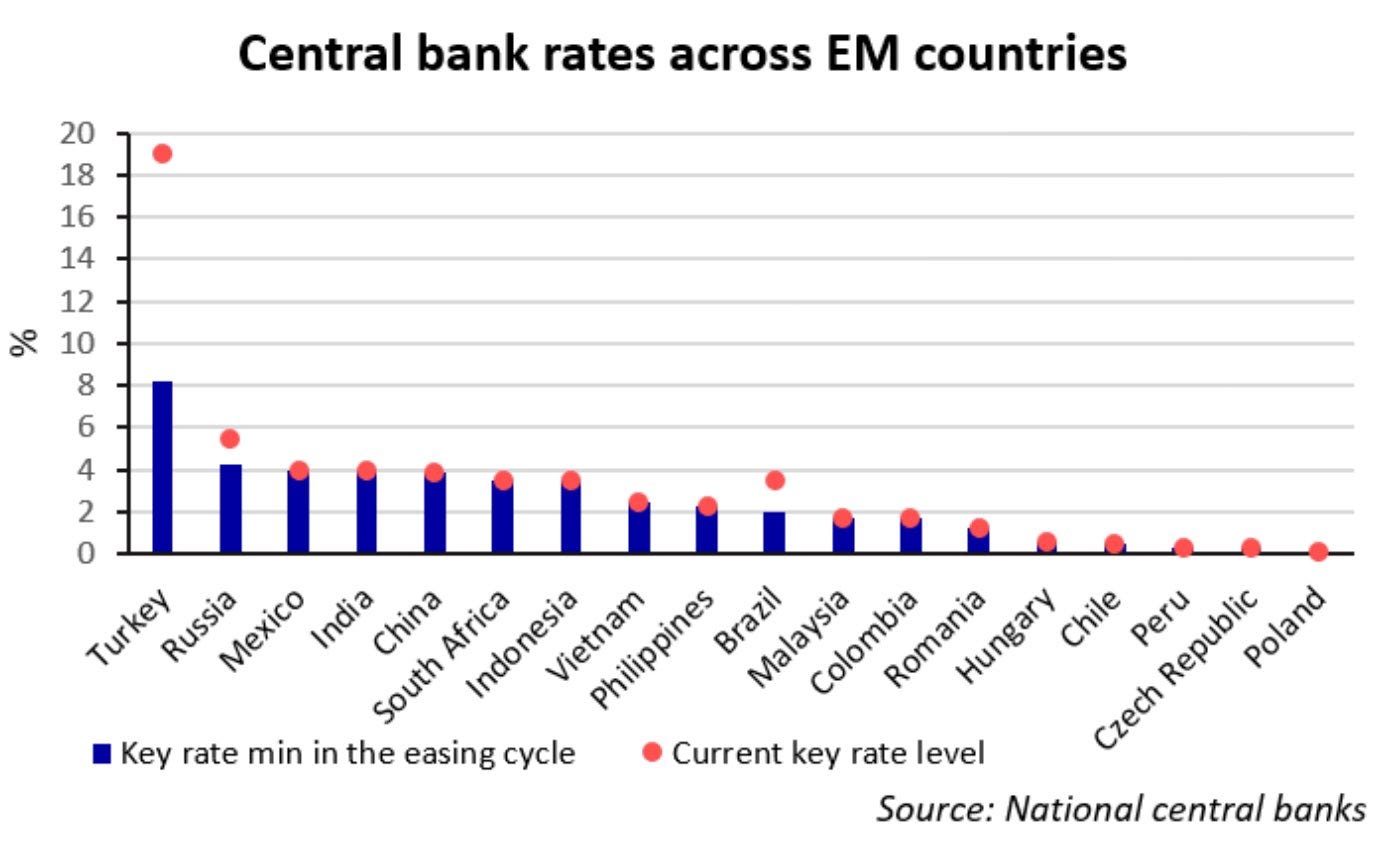

The Central Bank’s finally moved into the hawkish mode that I’d expected was implied by its earlier ‘neutral’ policy stance given how little the inflationary wave in Russia has to do with monetary policy. We can now see Russia’s only bested by Turkey in terms of the hawkishness of its monetary policy turn despite being in far better position than many others to finance its own borrowing domestically:

You can see that it’s begun pulling away in terms of its relative key rate level and is likely to move back towards 7% from the current 5.5% in the months ahead. It raises the question why since so many other emerging markets that ostensibly face greater monetary policy constraints aren’t following in tandem even when they similarly face concerns about consumer price inflation. Central Bank analysis on the state of the micro loan market shows that the pain from rate hikes will be quickly felt. Thought net new issuance of micro loans is declining, their monetary value is still rising. The consumer credit boom has finally caught up to households’ capacity to borrow and while more individuals are dropping out from borrowing to sustain consumption, the ones who can still afford to borrow seem to taking out larger and larger volumes per individual issuances as a result of both inflation and likely from the pressure to make big consumer purchases now before prices increase even further. The biggest effects will be felt for mortgages and short-term deposit rates. We’re back to 2015-2016, but instead of panicking about capital outflow, it’s a lower relative inflation level amid stagnation after years of falling real incomes. These policy choices will also mute some of the positive impact of rising oil prices on intermediate demand across the economy.

What’s going on?

Rosstat’s latest inflation release shows that aggregate price levels rose 3.7% for the first 6 months of the year, significantly above the 4% target and earlier forecasts in the 5-5.5% range. In fact, the current levels imply we’ll see inflation closer to 7.8% for the year at the current rate. The main challenges for price levels are all basically worsened not so much by the fact that the state intervenes in the economy, but rather the manner in which it does and the quality of its institutions. Competition is generally weak, so firms with strong positions don’t lose much from markups, tariff rate regulations for utilities and other public goods tend to undermine capacity investments over time and make the supply/demand balance more brittle, counter-sanctions on EU agricultural goods just increases the relative cost of certain imports as well as transaction costs, and the current price controls approach relies heavily on strong-arming wholesalers and retailers. But what inevitably happens is that the wholesalers have to increase prices to be able to maintain supplies of goods while retailers are expected to reduce their margins for the public good. None of this stops inflation. Rather it’s a political fight over who pays the costs of price inflation. Now parts of Russia’s media landscape are starting to wonder how the current situation compares to the 90s — inflation may be far lower in % terms than then and the system isn’t undergoing a massive depression like in the early to mid-90s, but the price of ‘stability’ for the Kremlin is that even marginal structural changes or shocks can have huge economic and political consequences.

Volgograd oblast’ authorities are complaining about the availability and quality of medical equipment being produced by domestic manufacturers per existing import substitution measures that have increased drug costs without adequately replacing imports (yet). But the lobby and ministries supporting import substitution efforts are wary of suggestions to increase the quality and production requirements are a backdoor to pay for imports if Russian medical producers can’t meet them. In a letter to Moscow, Volgograd deputy governor Valeriy Bakhin noted that plans to modernize hospitals requiring equipment for advanced care — X-ray machines, mammographs, and so on — faced considerable difficulties due to import substitution requirements for procurements. Though most other regional authorities contacted for comment either said it was a federal matter or refused to say anything on the record, we can see the influence of the security and defense lobby at work — Russian-made is fine even if it’s lower quality seems to be the default stance Moscow wants the regions to take even when it openly contradicts the injunction to improve healthcare systems strained by the COVID crisis. The situation is worsened by the lack of clarity in the regulations as they stand — MinPromTorg has clarified that customers can establish a ‘description’ for the equipment needed and if no analogs exist from Russian producers, there are no import restrictions. MinFin doesn’t want to rewrite the rules because it believes the existing framework allows enough leeway to contest restrictions. The solution? Come up with a new administrative organ responsible for properly cataloging what equipment does, variations in their capabilities, and so on. It’s a farce, and one that’s unnecessarily undermining what could otherwise be relatively valuable modernization programs reacting to the COVID crisis.

MinStroi, MinFin, and the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service (FAS) have begun communicating with regional governments to let them know that if price increases for construction materials (or labor) prevent the completion of state-funded construction projects, they will introduce new measures to allow for renegotiations for inputs to cap costs by changing contractual conditions. However, doing so would only cover about 10% of contracts currently under construction based on the construction of the initial proposal. Prices are a huge obstacle to the state’s desired investment plans — building material costs were up a net 16.4% year-on-year for May and of 846 billion rubles ($11.7 billion) allocated for construction, 42 billion rubles ($581.28 million) of that will be ‘lost’ to price increases alone this year. MinStroi and MinFin’s main proposed conditions for the contracts that cap prices are pretty weak: the project has to exceed 100 million rubles, contracts must be 1-year long, and price revisions can’t exceed a 30% increase. But over 90% of contracts per the National Association of Builders last less than a year. The political brains of technologists convinced that by magically signing a ‘long-term’ contract, one achieves price stability without consideration for the countless factors relevant to pricing and market signals have really taken over these types of discussions. Creative policy is important. Russia does face limitations more developed markets don’t. These, however, are the worst kinds of policy innovations because they’re designed to create the appearance of action instead of addressing root problems or challenging the assumptions held by policymakers in Moscow as to what actually works.

The demographic picture emerging from 2020 looks quite grim. Rosstat’s latest release shows that Russia lost 700,000 in population for 2020 after losing 317,000 in 2019 to natural decline/deaths. And that’s before counting the continued excess mortality caused bay COVID this year. The 700,000 figure is a revision upwards from the 500,000 announced by Tatiana Golikova and the ‘social’ bloc within government handling demography and related problems as of January. The problem, of course, is that in pre-COVID years, inward migration could cover most losses to natural causes. The 2020 migration figure is just guesstimated based off the scale of the loss of foreign nationals in the country as of 1Q this year, but is meant to show the scale of the shock compared to usual for the Russian economy. Following is in 000s and 2014 was excluded by Rosstat cause it’s an anomalous year and the population jumps post-Crimea annexation:

This is the one area where Russian policymakers are right to point to a supply-side shock. The labor market’s taken a huge beating on top of of the weak underlying trends whereby the state has been able to prevent significant wage gains for labor in real terms by exploiting illegal, semi-legal, or else fully legal migrant labor from Central Asia in particular while doing precious little to protect laborers’ rights. Now that the softening of labor laws and restrictions from last year, a crisis measure to buoy the economy, is coming to an end, labor migrants are going to face more pressures as they arrive and look for work. There’s renewed political interest from Moscow to harmonize and improve labor migrant regulations among EAEU members, but the more Moscow creates a stronger legal basis for workers’ rights and the ability to immigrate, theoretically the ability to shut down flights’ access — usually from Tajikistan — loses political coherence. What’s the point of a set of supranational legal arrangements and institutions if they don’t work when needed?

COVID Status Report

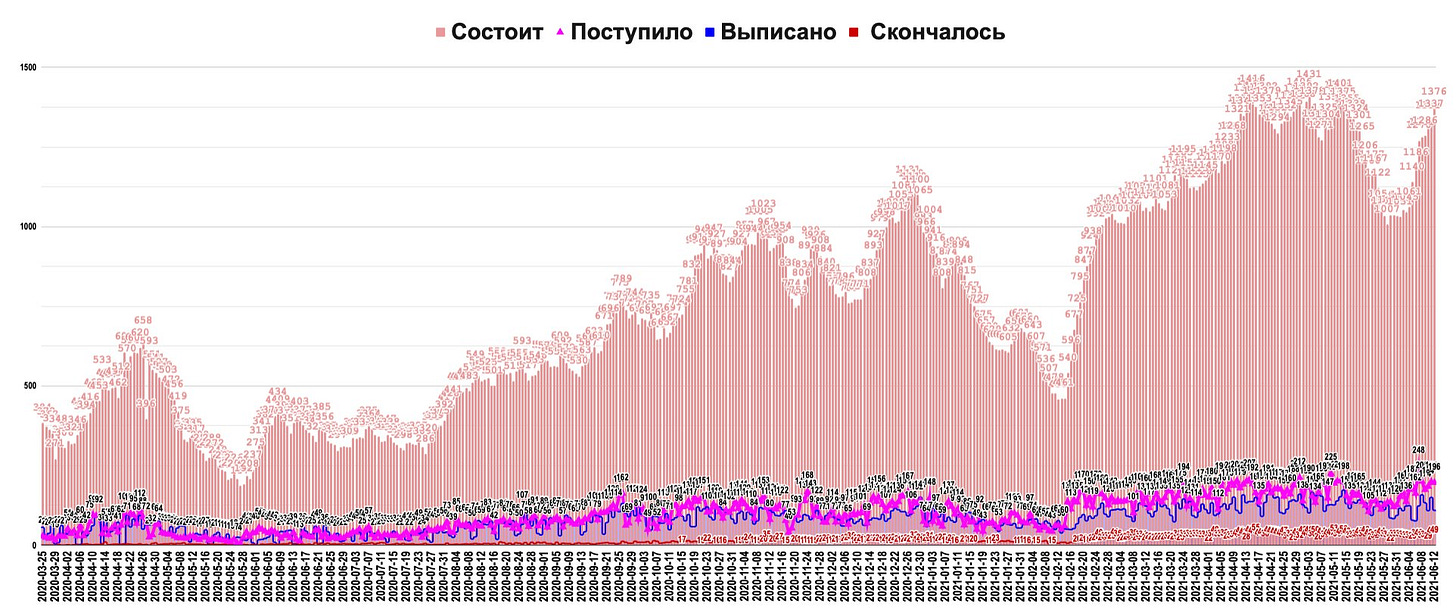

Yesterday saw 13,721 new cases and 371 deaths recorded — yesterday the new case load was 14,723. Moscow accounts for the surge in the official data, but data from the Kommunarka hospital in the city shows that COVID hospitalizations have remained high for months with a dip in May after the non-working day holiday was taken. H/t to Jake Cordell for grabbing this off of Facebook. It’s the bottom lines that matter most, but we can see from overall activity at the hospital as well that the pressure never really eased up:

Purple = admitted Blue = discharged Red = died

COVID restrictions are coming back. Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin called for another ‘non-working’ holiday from the 15-19th to halt the rise in cases, since yesterday, anyone who can work remotely has been told to do so, some attractions have been closed, and we’re back to the stop-start confusion of last year and earlier this year. St. Petersburg is similarly introducing additional restrictions from the 17th onwards. Gotta let 30,000 fans gather for a Russia-Finland match first naturally. Rospotrebnadzor is sticking to its guns — Anna Popova has reiterated that all restrictions will be lifted when 60% of adults are vaccinated or have immunity from having gotten COVID and recovered. Given just how far to go there is to achieve that level of vaccination, it’s going to be a tough summer. Check out this RFERL interview between Sergei Medvedev and Aleksei Raksha on what now officially looks like a third wave.

When you assume, you make an *** out of you and me

I had the pleasure of watching CNAS’ ‘Assumptions Check’ on Russia as a declining power, and finding the conversation rather wanting and evidence of both how questionable the claim that Russia is in decline actually has been as ‘consensus’ broadly prior to the last few years. The intention was to “right size” Russia as a threat to US interests, which is Swamp-speak for making sure one’s own pet interests and issues are adequately funded without intending to claim that Russia is anything like the challenge posed by China. Ahead of the Biden-Putin summit, it’s worth reacting. Before diving into my issues, it’s also important to be fair to the speakers — when you’re working within a half hour format, you have to be rather choosy about what you include and cut out for your analysis. Link below for the video:

The worst offender among the lineup is Eddie Fishman’s analysis of the Russian economy, leading with the oft-repeated claim that Moscow’s done a great job of keeping its fiscal and monetary policy house in order. It might be hard to be an everyday Russian, but from a macro perspective, things are in solid shape. Russia’s got its war-chest with Central Bank reserves and the National Welfare Fund and is ready to go:

Fishman’s broad strokes portrait of a country managed by competent macroeconomic managers amid systemic corruption is simply false. The Central Bank’s efforts from 2015-2017 were heroic, but ultimately fit into a fiscal policy framework shaped by an outright political opportunist — Anton Siluanov — and economic policy approach that has consistently degraded Russia’s capability to actually diversify its economy. In other words, this “competence” really just abets the incompetence, graft, and short-sightedness of political institutions and policies across the wider economy. The war-chest he points to is largely irrelevant as a success story because not much of it is generally spent, and when it is spent, it’s rarely spent well. Accumulation via export surplus to finance domestic investment can be a successful approach in specific contexts, but in Russia, what it really entails is the destruction of domestic demand to maintain that surplus, whether through orthodoxy monetary and fiscal policy or by clustering state resources and support in export-facing sectors with the intention of pursuing import substitution and industrial policy prerogatives. Most of these policy approaches end up increasing domestic costs and create a new class of rentiers living off of state resources and intervention. In short, Fishman launders the stability thesis without scrutinizing macro orthodoxy. What’s even odder to consider is what comes next.

Per Fishman’s comments, sanctions are too weak to have any significant impact on Russian power — this is strictly true, but basically assumes that Russian policymaking operates without any concern for sanctions pressures since 2014 — and that Russia’s economic decline hasn’t and won’t affect its power. Well, if that were strictly true, then Russia’s mighty reserves and export surplus should be able to sustain greater client relationships, ‘adventurism’ (I hate the term), or else not be shaping Russia’s policy toolkit at present. All three evidentially have been affected by Russia’s self-imposed economic weaknesses. The expansion of Russian influence in MENA and Africa is driven primarily by policy entrepreneurship, save Syria, and in the case of Wagner and other mercenaries is often a pale imitation of the Brezhnev years. The other problem with the formula Fishman provides is that it’s not just about Russia when it comes to power. In Central Asia, if Russian consumers don’t offer a significant outlet for value-added exports and production or conversely if foreign firms stop sinking FDI into factories to Russia to take advantage of its access to CIS markets because they’re also stagnating, the relative economic power that China and frankly any external power with deep pockets and an interest in development economics is increased. China hosted a diplomatic forum for the Kyrgyz and Tajik governments to discuss recent. border issues within a broader regional framework including other Central Asian states and Moscow never attempted to create a meaningful diplomatic parallel. Ukraine wouldn’t have drifted towards the EU in the first place if Moscow had done more to turn the oil windfall into more than just an import-led consumption boom — admittedly difficult but was of course possible. The examples go on, but it seems odd to simultaneously stipulate Russia is a stable economic great power and basically conceive of its international power only in terms of its military might. I fully agree that the Russian market can’t just be ignored or written off along with the rest of former Soviet Eurasia as they often are by most of the academic world concerned with international political economy. It’s a country that could rival Germany for economic influence globally. But it falls far short and its own policies and institutional weaknesses are the leading proximate causes of that today, though certainly not two decades ago. His notes on Russia diversifying its trade to Asia are important, but at the end of the day, lots of trade with China is still with European companies and importing tech and finished goods from China and Asia while selling it energy resources and food doesn’t actually change its economic predicament or ‘power.’ Trade balances on a bilateral basis don’t matter that much except when political decisions limits trade, they reflect structural domestic imbalances.

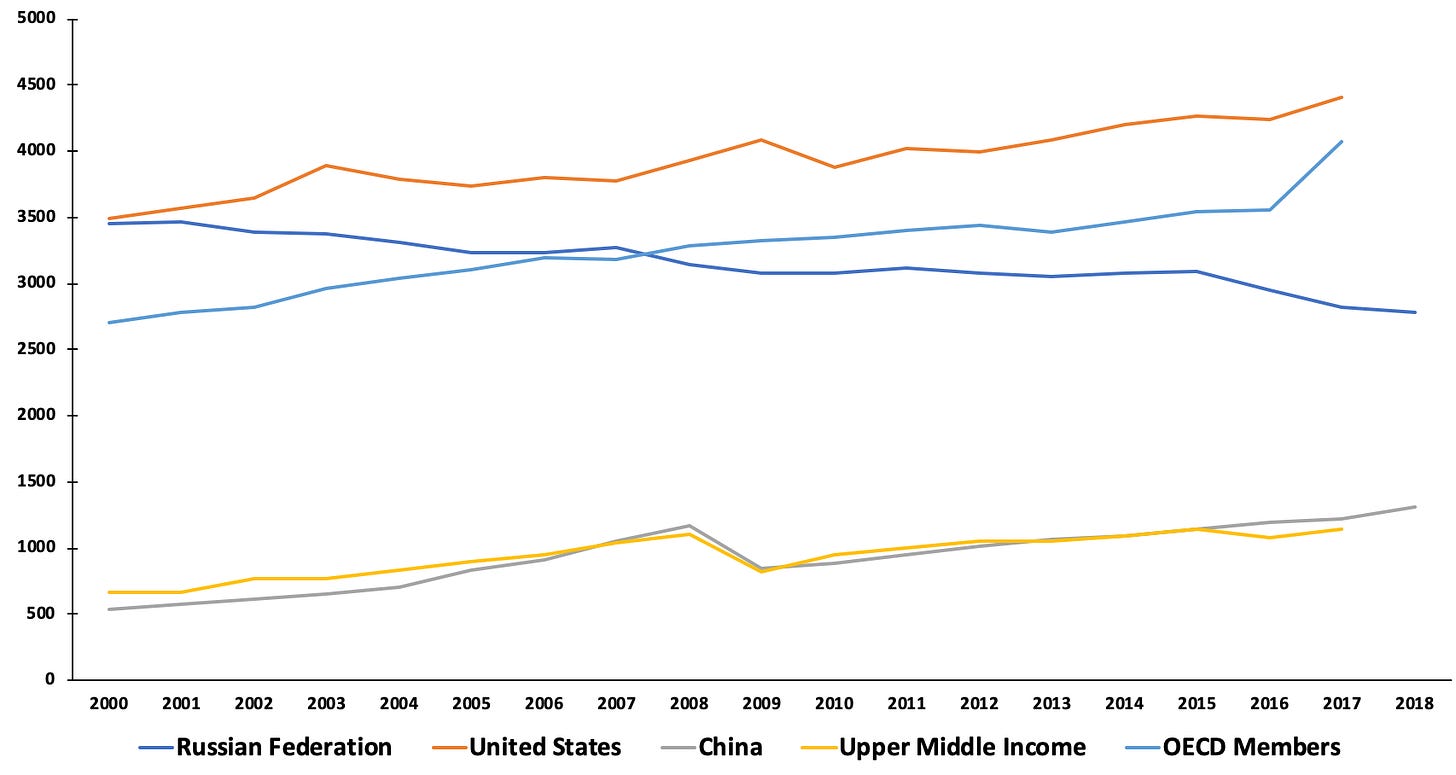

Rita Konev’s bit on Russia as a technological power was a useful reminder that Russia’s R&D capacity is highly concentrated in military applications and quite bad at commercializing innovations. It’s still relevant for specific measures, despite challenges retaining educated talent and chronic underfunding, but also nothing like a ‘pacing challenge’ like China. Just look at how much the rentier state (re)formed after Putin came to power has worn down the large body of researchers left over from the Soviet period, effectively squandering what could have been a strong basis for future growth and competitiveness. Data only goes to 2018 for Russia and China and 2017 for the US, but the trends are probably still on track. World Bank data shows # of researchers per million people:

Russia was basically tied with the US in quantitative terms around 2000 and has seen the steady and systematic decline of the cadre of researchers it has. The improvements to human capital indices would suggest getting more out of the workforce it has, but not that it’s using innovations effectively or else hide that decline compared to the US and OECD where human capital indicators are better and, perhaps most importantly, exist in a political and market ecosystem where innovations can be adopted, though there’s plenty to be done to improve that process.

Mike Kofman’s bit on Russian military strength is one that’s really important to sit with because I tend to agree with him about Russia’s capacity to do more than it currently is militarily, but also think questions about the viability of that military power longer-term and its domestic costs are far more significant than he generally argues. Setting aside issues with his use of human capital indicators in Russia — one can ‘teach to the test’ with them for lots of purposes and still recklessly misuse human capital as is systemically the case in Russia — the problem applying the generally conservative PPP adjustment for Russian defense spending pegging it at $150-180 billion annually isn’t about the scale of Russian capabilities. It’s a really useful exercise given Russia makes its own arms and funds military research. The problem for ‘power’ purposes is that the quality of the resources available, of human capital, of access to credit, or other qualitative indicators for the defense sector are generally better than you’ll see in much of the economy. The efficacy of that $180 billion spent on defense is likely higher than $180 billion spent on infrastructure, housing, domestic industrial subsidies, and so on. You also have to factor in what’s actually generating purchasing power across the Russian economy. Rosstat’s recent pivot to use a far more accurate median account for wages institute of mean has effectively revised the figure used for the average Russian’s wages down by 37%. And this also is operating in an environment where Moscow tries to cap costs for the defense sector to bury the real level of spending, which is undoubtedly higher than what we see publicly. So the issue isn’t so much whether the current macroeconomic framework can literally support these levels of spending, but rather the opportunity costs associated with spending because of the self-imposed scarcity of financial resources per the existing macroeconomic framework. Add in the political limits of what the regime can do and I actually don’t know one can credibly claim Russia can really do that much more than it is, otherwise one has to explain why it’s limited itself the way it has to secure its interests if we take seriously the degree to which policy in Moscow is operating with a siege mentality in mind. Of course, Russia isn’t the US. It’s not burdened by the same psychological onus to do something merely because it can. It’ll be interesting to see what will happen with Afghanistan should Russia be forced to commit AirPower.

There’s also the issue of which people you are actually recruiting into the military, which interacts with Russia’s management of its labor market and fiscal/monetary policy approach. Take the following Levada poll showing an age demographic breakdown of who owes mortgages and consumer debt that has to be paid off:

People under 40 are more indebted as a % of the total population to sustain their living standards and the Russian military has benefited from the political management of the labor market. The system seeks a politically optimal level of employment probably higher than the traditional measures of NAIRU (that never made much sense…) in western economies, but supported in a manner that undermines productivity enhancing investments. People get desperate, they look for stability. That may end up being a positive for recruitment, as was often the case during the worst of the manpower crunch in the 2000s the US faced.

One of the odd things to factor in, though, from Kofman’s comments about quality vs. quantity of human capital and the recruitment pool is that most of the newer jobs being created are lower wage and less-skilled, with freelancing absorbing a fair bit of the the higher-skilled work. You can’t really trust the official data about skill-level and labor, not because it outright lies, but because it classifies a lot of activity intended to paint a prettier picture about moving up the value-chain than makes sense. It’s inconceivable that human capital is enjoying a renaissance when Russia’s services sector is constantly dealing with falling incomes and the state’s massively inflating the profitability of financial services and banking. In short, it’s just as likely that the economy is creating labor-intensive jobs that’ll compete with the military based on its current ambitions. Conscripting prisoners to build railways also suggests that we may see the normalization of yet more mobilizational tools, whether they be for the defense sector or else to cap costs for infrastructure investment. Those are things that suggest Russia’s ‘light touch’ approach to Syria, for instance, can be easily replicated elsewhere. That does not suggest that it can be replicated without domestic political costs unless the regime keeps expanding the repressive apparatus without any material improvement in living standards. Tatiana Stanovaya’s recent piece on the growing horizontal nature and expansion of repression affects institutional capacity to govern. Look at the disastrous response to COVID. Compare it to China. Arguing against decline requires a far more holistic rendering of ‘power’ in rival states and how institutions interact with economic realities, political concerns, personalist whims, and more. Decline, like going broke, happens slowly and then very quickly. The West needs to start talking about disaster planning too and construct a positive vision of what it can offer Russia down the road instead of (mostly) hollow summitry.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).