Top of the Pops

HFI Research has it out that China disproves the thesis that COVID-19 will create a structural drag on demand. What they seem to leave out of the analysis is that China’s total demand recovery has, for now, a structurally deflationary effect on economic recoveries elsewhere and that fiscal spending plans, at least in OECD countries, are generally going to accelerate demand destruction for oil as a road fuel. In other words, it’s looking at the problem only in terms of oil without factoring how oil is consumed: with money that people have to earn and spend somehow in economies facing huge levels of policy uncertainty and impact in the short to medium-term. Market bulls shouldn’t be ignored, but if they aren’t factoring in that one man’s inflation is another’s deflation without coordination, they’re missing a key piece of the puzzle.

Tomorrow, I’ll be doing a less Russia-centric newsletter and diving more into what’s going on across the broader Eurasian neighborhood when it comes to COVID-19, energy markets, economic recovery plans, and, well, events in Belarus, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Kyrgyzstan

What’s going on?

Sber is launching a pilot program to track Russians’ transactions, match them up with geodata, and then selling their analytics tools and content to businesses and regional authorities. On the one hand, this is clearly going to become a surveillance tool for the Russian government via SOEs and a source of huge future procurement contracts and rents for Sber (assuming it works). On the other, the company has committed to keeping data anonymous and, frankly, has some good reasons to do so. MinFin supports OECD efforts to coordinate digital tax collection for international holding companies, and Sber is keen on expanding onto the Chinese market. Expanding financing and letters of credit with Chinese banks is one thing, but ensuring any internal data doesn’t get stolen by Chinese counterparts is going to be another. Still, the FSB and other blocs are most likely going to demand a backdoor into the system.

Rail wagon manufacturers led by Uralvagonzavod are asking for more help from policymakers to address the surplus of 70-100,000 gondola cars on the network (roughly 8% of the total fleet on the Russian rail system at the moment). The surplus drives down rental rates for shipping and is expected to cost wagon manufacturers 50 billion rubles ($642 million) in earnings this year and reduce output by a third to 50,000 wagons. The hope is that they formally mandate write-offs for older cars in the fleet, forcing companies to buy new production. I doubt that’s effective stimulus without a broader demand recovery, but deflationary pressures for rental rates and costs for wagons will probably help rein in consumer price inflation in the regions slightly.

Izvestia reports that MinFin is looking to cut defense spending, proposing a 100,000 man reduction in military personnel, cutting corners on costs for clothes and related gear, limiting compensation for contractors to periods when they’re deployed in the field, and more. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov is firing a shot across the bow given the military’s generally sacrosanct place for the Russian budget. Even before these cuts, however, the portion of Russian GDP that is covered by classified expenditures i.e. the defense budget has declined from its 2016 peak, though that’s also due to the end of economic contraction and return to stagnant levels of growth:

Title: The Secret Share of Russian GDP, trln rubles

Grey + total figure = GDP in current prices Light Green = fixed capital accumulation Green = closed part of budget outlays for fixed assets (weapons systems + intellectual property)

Note that this is from this August and 2019 data is not yet published.

The Ministry of Labor is taking heat over its standard for calculating the wages necessary to be living at or above the poverty line. Critiques cite 14,000 rubles a month for 2021 as an adequate figure, 25% higher than the current proposal of 11,600 rubles which, per the first reading of the bill submitted to the Duma, is calculated in relation to Russians’ average per capita incomes rather than the costs of consumer goods. That’s lunacy given the wage gaps between cities, regions, and the complexity of regional income coefficient adjustments for costs of living. It’s sure to be an area of some contestation given how many poor Russians have children and large families.

COVID Status Report

RBK’s done a good job visualizing the week-on-week % increase or decrease in infections in Russia:

The weekly growth rate of new cases, %. Comparisons are week-on-week. Focus on the period after the start of May when the number of daily COVID tests broke 200,000

There’s some reason to hope that remote work measures and related attempts to track and trace in Moscow in particular are having an effect, but there aren’t clear parallel efforts in the regions. What’s more interesting now is that Vasily Ignatiev from P-Farm - the frontman selling the Sputnik-V vaccine - has now said that mass vaccinations in Russia could start by November or December. Sputnik-V entered mass production on August 15, so it’s clear that the presidential administration has been waving off strict lockdown measures based on an assumption that they can get a vaccine out in time before the worst economic damage is realized because of their failure to provide adequate levels of support and stimulus.

The Conquest of Bread

While doomscrolling last night, I stumbled across this graph from Tatiana Evdokimova that neatly summarizes how Russia’s managed to weather 2020:

It’s nothing new for most of you, but it does point to a question that has to be answered now that COVID-19 has roiled the world of oil & gas: how much can Russia’s non-oil & gas exports grow? It’s something I’m thinking a little more about now since we’re not going to have any clarity on OPEC+’s cut extension plans until the end of November. So what exactly can we expect elsewhere in the Russian economy given the novelty and myriad difficulties posed by the current crisis? It’s worth looking at budget politics given how closely they track with Russia’s current account. Note that I’ll look around for more comparative data about sectors later on and try to come back to the topic with more depth at some point, ideally as the budget is rolled out to find different sectoral compromises that might not be making headlines.

It caught my eye that during the current budget talks, the Duma’s looking to increase subsidies for the agricultural sector from 371 billion rubles ($4.8 billion) in 2021 to 435 billion rubles ($5.6 billion) by 2023 - presumably keeping pace with inflation. The goal is to avoid a drop-off in investment into Russian production in the current crisis environment, and a logical one for the future of Russia’s current account. Vice-speaker of the Duma Alexei Gordeev - agricultural minister from 1999-2009 and governor of Voronezh oblast from 2009-2017- is leading the charge for the lobby in Moscow calling on the Duma not to vote for a budget failing to support the sector adequately.

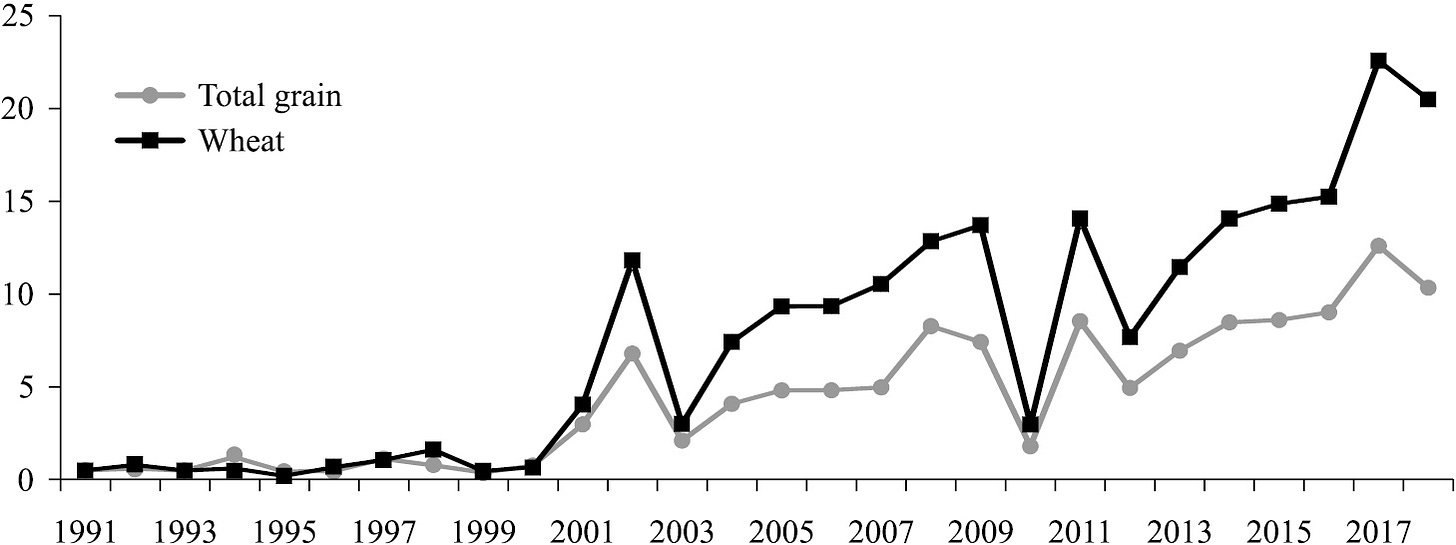

On its face, this is a story about trying to develop another sector to meet external demand and increase export earnings. That would help manage the ruble exchange rate and provide sectoral growth in a largely stagnant economy. But up close, it’s not quite so clear cut. A few years ago, a shortage of rail wagons literally pushed the governor of Leningrad oblast to write a panicked letter about potential bread shortages despite surging wheat exports. The attempts to funnel money into production should, in theory, suppress domestic prices and encourage producers to sell for export and earn a higher markup after meeting domestic demand. But that assumes that Russia’s infrastructure keeps pace. Bottlenecks contribute to higher domestic prices, which end up undermining continued export growth and increasing price volatility because of potential over-investment into capacity without matched investments into road and rail capacity to ensure that supply chains operate smoothly. Wheat has been the one of the biggest success stories for the Russian economy since Putin’s land reforms adopted early in his first term as president:

But that increased share of world exports is bound to face some interesting competition in the new COVID world. The trouble is Russia’s grain export quotas and their impact on businesses, domestic prices, and the current account. The EU overtook Russia as the world’s leading wheat exporter this summer because of export controls imposed to prevent domestic price inflation. MinSel’khoz is now arguing to preserve the quota mechanism - a physical cap on exports - for the long-term regardless of the expected good harvest this year. Those controls, however, operate inefficiently for price equilibria between the Russian market and world market due to the idiosyncrasies of Russian infrastructure and its freight markets.

For context, the latest government stimulus plans as of mid-September called for 1 trillion rubles ($12.8 billion) of bonds to be issued specifically to finance the construction of infrastructure and housing. Though an imperfect comparison, that’s less than 1% of Russia’s 2019 GDP in nominal terms, and that’s before accounting for rampant cost inflation with procurement contracts and related mechanisms allocating state resources to such projects. As of last year, VTB flagged that Russia would need $1 trillion in cumulative infrastructure investments to reach the level of a developed, western economy. All is not lost. RZhD has reported getting container train speeds for routes longer than 2,600 km above 25 km an hour - a huge improvement over where things stood a few years ago. What that really means, however, is that operators are probably prioritizing long-distance freight and trans-Eurasian freight to try and collect higher fees over shorter hauls when they can (the average freight shipment moves something like 1,000 km in Russia, need to check the sourcing again for that). Still, that’s a significant improvement in the quality of shipping services.

Any attempt to ramp up investment into agricultural production capacity to meet export demand is going to lead to a more volatile marketplace in Russia if infrastructure ends up creating or recreating bottlenecks. Direct export quotas are going to be a drag on profits rather than using tariff quotas whereby x amount faces a certain tariff beyond which the tariff rate adjusts. Unless there’s a breakthrough with China on market access, I’m curious to see where they intend to dump excess output and if the latest policy push plays with existing inflation-deflation dynamics on the market while other producers in the EU and further afield more efficiently invest into productivity gains because of a better equilibrium between domestic and international prices.

Kid Kudrin

Looks like Kudrin’s playing ball in an attempt to save Russian GDP and some space for marginal reform. In an interview on the 15th, he came out saying that cutting Russian defense spending to 2.5% of GDP is lower than the “optimal” level for national security. He prefers his old commitment to the 2.8-2.9% range. The gap’s not that big, but suggests that he’s not on the same page as Siluanov, or else would prefer to see salaries raised after they cut the military’s size by 100,000. At the same time, he’s clearly fighting for a 500 billion ruble ($6.4 billion) increase in spending rather than cuts to target support for social spending. That’s about 0.5% of GDP.

By no means does Kudrin have that much heft to get his way anymore, though he at least has been given a platform to constantly rap the knuckles of other ministers and leaders who don’t seem to understand that private debt is not going to save Russia’s economy. Still, tracing these types of statements while Russia’s budgeteers and oil sector hope for higher oil prices is a useful exercise to grasp the contours of policy debates that generally lack coherence. It’s especially stark given that the media is running interference: media mentions of the keyword ‘self-isolation’ during the current wave are down 96.4% compared to the first wave and references to the word pandemic are down 71%. It’s really all hinging on oil prices.

Kudrin seems to think that oil will be stuck in the $40-45 a barrel range for the next 3-5 years. The current budget rule may make that work in fiscal terms, but it’s a terrible signal for the business cycle. Figures like Reshetnikov at MinEkonomiki might offer some interesting insights into just how badly the ministries have given up and how much farther attempts to reimpose state controls, directly or indirectly, over the economy are going to go since economic downturns strengthen state-owned firms and state-centric lobbies most closely tied to the budget, sovereign debt rating, and access to cheaper capital. No matter the rhetoric, that’s the way things are cutting at the moment.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).