Top of the Pops

I missed this last week, but it’s worth flagging since it speaks to how market innovations introduced primarily by foreign firms — think Robinhood making an addictive app out of the service that outlets like etoro provide in this instance — end up posing serious structural risks and problems for markets like Russia. The Central Bank finally got around to tracking the money individual investors were putting into the market via brokerage accounts:

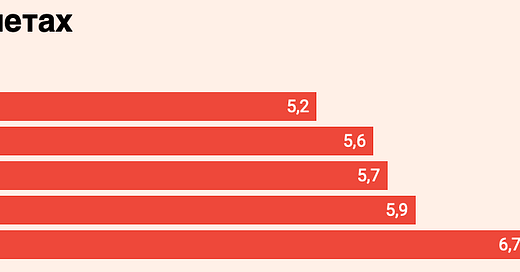

Title: How brokerage assets are growing, trlns rubles

As we can see, there was surge of 800 billion rubles ($10.87 billion) of savings invested between the end of June and end of September, a massive movement of capital after comparatively little action the first half of the year. Yes, people being trapped at home and also seeing bank deposit interest rates lag consumer price inflation encouraged people to do it. What I think is more interesting, however, is that the relative cheapness of stocks after their early crash in February-March drove the phenomenon in the OECD. In Russia, it’s not like the state’s stimulus plans did as much lifting for equity values — the commodity price rises in H2 certainly helped and beating macro expectations did as well. If the brokerage account trend continues in Russia — the CBR has backed off of harsh regulation realizing that most of the risk was centralized to a few investors who know what they’re doing generally — I’m waiting to see investors shifting around their investments as oil & gas underperform, even if shorter-term price rises aid equity values and revenues in the next few years. Protecting the environment has already become an organizational force for local protests and political activists engaging political institutions. The question in Russia is when it becomes one impacting what domestic investors want since they’re a crucial group for Kremlin economic policy in the longer-run if it wants to avoid exposure to foreign capital and market gyrations as well as develop adequate domestic sources of capital for investment.

What’s going on?

MinFin is working up a mechanism to attract private sector investment from industrial firms that receive state subsidies in order to improve their efficiency. There’s a huge problem now for publicly-traded firms receiving support — they turnaround and use subsidy schema to pay out dividends for shareholders. MinFin wants to mandate that all net profits from projects that are subsidized by state programs must be reinvested into production and productivity. It’s part of a larger push for legal frameworks taking effect in 2022 that will require any firm receiving subsidies to actually account for how they were used. The real aim here is to use it as a ‘transitional’ measure to increase capital investment across the economy amidst budget consolidation, another version of the “optimization” disease that plagues most of the Russian government. Business lobbies are already clarifying that in some cases, dividends could still be paid out effectively using subsidy support. It’s a neat solution, and a smart one to improve the effectiveness of state spending, but it also is likely to create disincentives for companies to take subsidy support for capital investments in the first place if they can’t retain the profits, thus making the scheme another potential source of musical chairs and arm-twisting without stabilizing the investment climate significantly.

2020 data through November shows that Russia’s cheese product output rose by 5.8%, driven by a mix of higher demand with lockdowns and falling incomes. Cheese products are what they sound like here — substitutes for cheese that use vegetable fats, including palm oil:

Title: Production of cheese and cheese products in Russia, thousands of tons

Orange = cheeses Light Blue = cheese products

As you can see, 2020 figures are set to match 2018 levels and the rise in cheese production in 2019 likely reflected higher incomes buoyed by oil market stability at or above $60 a barrel as well as a brief price rally in late 2018 that fed into other parts of the economy. I’m curious and have to dig around more, but the shift in consumption, even if small, is a useful indicator for both where household finances are at. Rosstat data cited shows Russians spending 43.4% of their income on daily needs like food, which is a bad sign for the durability of longer-run consumer goods consumption. Cheese prices were up 7% year-on-year in December reflecting the broader trend of higher net inflation for staple goods. It seems that more Russians ordering food at home has helped — pizza and burgers use more cheese than a lot of other staple dishes would.

Kommersant’s Dmitry Butrin writes quite convincingly about the biggest success story of Mishustin’s time as Prime Minister thus far: he’s managed to corral the government to unify its efforts to respond to COVID and internalize disagreements into the decision-making process so that no public fights appear and cause headaches. The result has been a much smoother operating environment for Mishustin to set about improving the efficacy and digitalization of state services, a prime directive when he got the gig stemming from his success modernizing the Federal Tax Service. In effect, Mishustin has proven quite capable of pursuing reforms to social spending and programs that Putin clearly wanted with his 2018 re-elect as a matter of course correction from the mistakes of the post-Crimea policy and political environment. My take is that Mishustin has done well to shape the policy process in such a way that he has become its central organizing figure (on domestic matters) without appearing to have a coherent elite base of support that might threaten anyone else’s political interests. In effect, he’s confirmed that he’s simultaneously harmless and competent. No one gains from removing him, the only people who lose from having him there are people that the presidential administration doesn’t mind upsetting if need be to achieve political objectives. It also explains why it’s gotten harder to track business developments in the last year in some respects. There’s not as much cross-briefing for at least some of what I cover, and I count that as likely a shift in managerial style in the cabinet and between the ministries as a result.

There’s a fairly clear consensus among Russia’s economist class — note that these people aren’t necessarily anywhere close to policymaking — that Russia is entering its second decade of stagnation after the COVID crisis with little left to help it grow. A mix of concerns over external demand i.e. weak global growth, evident changes in trade and industrial policy that will affect the structure of output in developed economies and China, the effects of growing digitalization, and rising inequality all pose huge problems for Russia. While one could argue that Russia’s import substitution programs have helped alter the structure of production, import substitution requires healthy domestic demand to function, and is worthless as a strategy to improve export competitiveness unless incomes are strong enough domestically to absorb initial output and help domestic firms (or even factories that have been localized from abroad that are run for foreign ones) get on their feet. The National Goals explicitly state that incomes should rise in line with inflation through 2030, abandoning serious ambitions to improve standards of living. None of this is news, but what is telling is that Russia’s academic and policy institutions know they have little influence over policy outcomes during this crisis, creating parallel economic discourses that fail to interact and inform each other. Compare this to the evident lessons learned from the global financial crisis in the United States and shifts in consensus. The political system has thus closed off any feedback loop from its economic experts save those who still preach monetarism, supply-side economic policy, and other imported ideological frameworks filtered through a Soviet lens lacking any domestic substitutes. That’s where the lack of growth drivers starts.

COVID Status Report

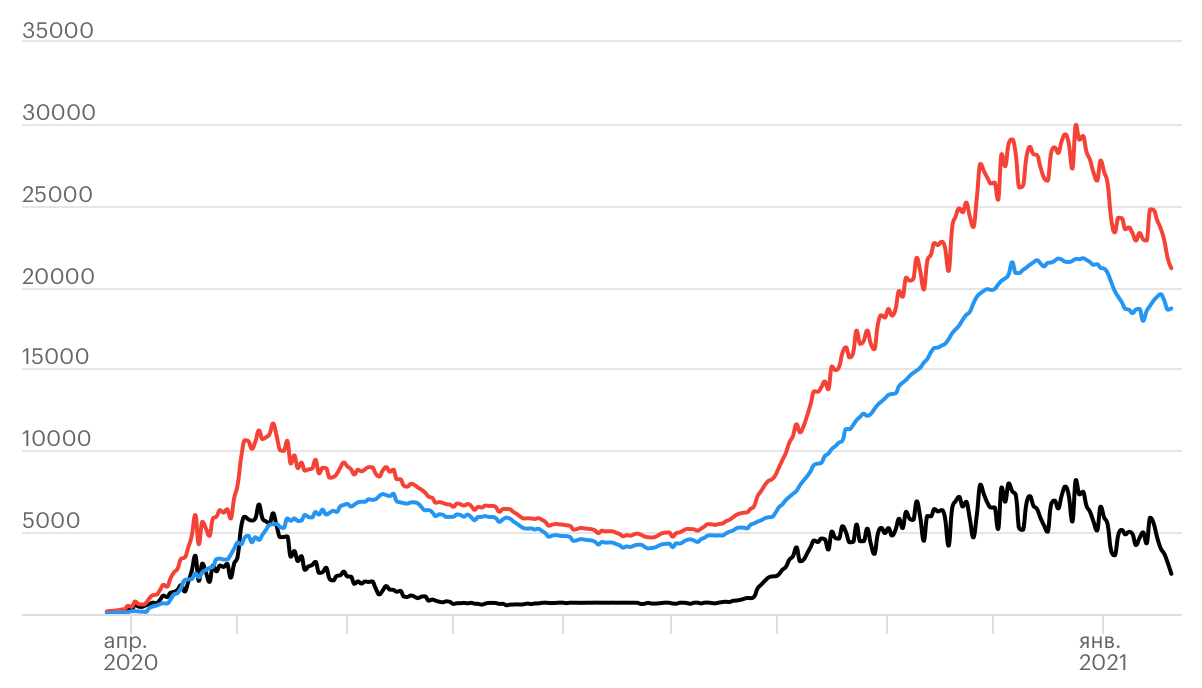

Cases dropped to 21,152 and while reported deaths rose to 597. The net infection figures were largely influenced by a big drop in Moscow. My pet theory is that MinZdrav is trying to funnel vaccines to Moscow to accelerate the vaccination rate in line with Sobyanin’s promise that the city will reopen in May, providing the added benefit of making it look like the virus is under control when the regional figures are largely stagnant and still waiting to see what impact the new strain(s) have, if any:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

While more government officials lay groundwork for a serious policy debate on COVID passports, it seems that 59% of Russians are opposed to them. That’s going to hurt the supply-siders’ dream of everything going back to normal for those who’ve been vaccinated or have the antibodies. Valentina Matvienko, speaker of the Federation Council, is adamant that a COVID passport will not be introduced. It seems they’re reading the polling and thinking about the logistics of inventing yet another registry in the middle of a crisis they barely kept a lid on that will cost them support in the September Duma elections. Now that vaccinations are taking place across all the regions and shortages are being openly acknowledged, the issue will undoubtedly be more salient politically in the next month or two, no matter what the regime lands on it. My money’s on ‘no passport’ for now.

Crude Boys

Vedomosti ran a piece yesterday evening that caught my eye: ‘Joe Biden prepares a gift for Russia’. The piece makes the argument, correctly, that Biden’s public announcement that he’ll sign an executive order to spike the Keystone XL pipeline will give Urals blend a small demand bump on the market. I figured it’s worth pausing over whether or not it actually makes strategic sense for the US, and what impacts it has on the market so that one can better understand the political significance of the decision, how it interacts with the climate agenda politically as well as the distributive politics of the energy transition, and how to think about the interconnected consequences of these decisions. Biden will be reversing Trump’s reversal of the Obama administration’s decision to kill the project in 2015. There’s a lot going on.

The trouble now is that the Trump administration’s sanctions regime on Venezuelan crude as well as the collapse of Venezuelan output (not necessarily a result of sanctions) has affected the United States’ import balance for crude because of the loss of access to supplies of heavy crude used by American refiners for refined products like heavy fuel oil (think fuel for generators, now being phased out slowly from shipping), bitumen (used for asphalt and road surfaces), and other lower value end products. Otherwise refineries have to spend a fair bit more removing impurities to yield higher-end products. Given the size of the US economy, its road construction and repair demand, its daily imports and frequency with which fuel oil is used in non-shipping settings, that shift in crude flows was significant.

Canada alternately produces a lot of heavy crude, most infamously from the Athabasca Oil Sands in Alberta considered to be one of, if not the most carbon-intensive and high-polluting major oil project on the planet. Alberta produces in the range of 80% of Canada’s oil — Canadian producers extracted about 4.7 million barrels a day in total in 2019, as much as Iraq and lagging Texas by roughly 370,000 bpd. Canada consumes about half of what it produces, thus exporting (in a normal year) in the range of 2-2.3 million bpd. But it has a huge geography problem: its domestic demand is centered in the east and near the US border, whereas its oil producing regions are further north and away from the coasts. It therefore makes more economic sense to import oil to meet domestic refined product needs in many cases, and Canadian oil sold for export trades at a significant relative discount, both because of its frequently heavier, dirtier quality and also because of the logistical constraints on firms’ carrying capacity away from oil fields. Keystone XL was meant to expand existing takeaway capacity by pipeline from Alberta to the Gulf of Mexico:

The expansion would have done a three things: improve Alberta’s carrying capacity, reduce Alberta’s steep export discount, and make Alberta more viable for future upstream investment. For context, Alberta’s crude is broadly traded at a discount relative to West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude in the US, which itself trades at discount to North Sea Brent (currently in the range of $2-4ish, but historically higher due to limited carrying capacity from the Gulf and US export bans) which serves as the international benchmark because it yields the most balanced combination of refined products. But Alberta’s discounts against WTI are terrible due to logistical constraints and geography:

We’re talking regular discounts in the range of 20-40% during ‘good’ oil demand markets. They skyrocketed to 60+% in 2019. If you were drilling Alberta crude, you were selling crude at about $22.80 a barrel when shale drillers in Texas could net $56.99. You don’t need to be an energy economist to realize a price discount that steep for crude that’s in high demand on a huge neighboring market like the US is murder for investment. Trump was even crazy enough to throw his weight tentatively behind ok’ing permits for a proposal to build a railroad from Alberta’s main oil fields connecting to Anchorage, Alaska by way of Fairbanks to improve the viability of Alberta’s output. As it stands, Albertan producers face limited existing capacity south down to Cushing, Oklahoma — one of the main distribution hubs in the US for reference pricing — and east-west railways in Canada that aren’t fit to expand production and export volumes. With the pipeline expansion built, discounts would fall, investment into upstream production would rise, the US could import more from Canada instead of relying on Venezuela — this would be more useful leverage than the existing sanctions regime — and crucially, it could have helped keep oil prices lower for even longer. The best way to defang OPEC and Russia’s oil-producer power is to make sure the oil market functions as closely to a transparently traded market as possible with as limited a political risk premium for pricing as possible and limited scope for swing capacity or else politically-motivated production decisions in major exporters to ‘short-circuit’ the business cycle that corresponds to oil prices and leads to peaks and troughs for upstream investment.

Setting aside the very drastic negative environmental impacts suffered in Alberta, particularly by the First Nations living there, the environmental arguments in the US were largely symbolic. There’s pipeline infrastructure all over the country that works with limited incident and whenever you hit national park land or places that really need to be preserved, there’s generally a routing workaround that can be agreed, though by no means does this remove the risks of contamination and accidents that come with any hydrocarbon project by its nature. Keystone, however, became a symbolic litmus test that politically hurt the Democrats. I was interning in the Senate during the 2014 midterms and senators like Mary Landrieu (D) in Louisiana were desperately trying to hold onto their seats and advocating for the project since it’d benefit her constituents. Coastal Democrats didn’t care since their political bases expected a No vote and weren’t much affected by the outcome materially, yet the original proposal dovetailed perfectly with the lifting of the ban on US crude oil exports that followed in 2015 as a strategy to further weaken Russia structurally at the time. The problem was that the project was visibly at stake when oil prices were low — supply security wasn’t on the public’s mind since gasoline was cheaper — and no one had moved the ball on carbon taxes. It was obvious to anyone watching floor speeches just before the election that moderate Democrats needed a legislative win that would depress Republican turnout by delivering something many moderate Republican voters wanted while securing jobs, some of them unionized, for their political bases back home.

Ironically, by lowering the differential discount for Albertan crude blends, it would be much easier to tighten environmental requirements mandating companies spend more on mitigation and the elimination of emissions and waste, whether that be by taxing carbon or else through delegated regulatory powers from environmental agencies. Similarly, there was still more optimism about future demand growth at the time. Though I fully understand why it went the way it did — the jobs Keystone XL promised were always overblown and activists raised completely valid concerns about land rights (Standing Rock in particular) and potential environmental damage — it was a mistake that undermined the United States’ ability to leverage its rise as an oil power to pursue a coherent grand strategy abroad, diminish the power of what became OPEC+, and use a lower price environment to begin passing legislation that would raise the cost of carbon precisely when consumer end-costs were lower to “hide” some of the inflationary effect and jumpstart the wave of R&D and capital intensive activity to improve energy efficiency and encourage fuel substitution that it’s taken COVID to really accelerate.

It’s funny now to think that a business daily in Moscow would pick up on this story in a way that the US media never has. Biden clearly is doing it to please his caucus, since the party shifted noticeably left after the 2014 losses having washed its hands of competing in places like Louisiana. It’s still a point of concern for Russia. Last April, Alberta’s export woes were at a particular peak and the province had begun imposing production limits to keep things afloat. FT reported that the Canadian and American governments had discussed the possibility of placing tariffs on imports of heavier Russian crude to prevent them from being more competitive than Alberta’s output and give Albertan producers a chance to claim more market share and stay afloat. Biden’s foreign policy team is a lot more hawkish on the whole, save General Lloyd Austin and his inner circle, than Biden lets on. Anthony Blinken’s testimony on Georgia’s potential NATO accession — a valid position, though one with many problems — inartfully revealed that the State Department will likely be happy to go full bore finding ways to jab at Russia around the edges without defining a clear endgame or strategy on their part. That’s only going to empower more hawkish members of the National Security Council, including the hawk in slender man’s clothing Jake Sullivan:

Biden’s revocation of Keystone XL will barely get any coverage once it happens, and few will stop to look back on what it could have helped do for US national security and strategic interests because of the attendant environmental risks it brought. It’s still worth a look if you’re in the weeds on Russia’s oil politics. Global markets for fungible commodities are a brutal, constantly moving ballet of unstoppable forces and immovable objects colliding. Giving Ural blend even a .50 cent boost on its usual discount to Brent — this dynamic flipped somewhat due to US sanctions on medium, sour production in Iran and Venezuela — can make a significant difference for Russian firms calculating recovery costs per barrel against their breakeven prices and export expectations. It won’t help Russia’s oil sector much, but in an age of ever diminishing expectations in Russia, I’m sure at least a few people will be taking the little W.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).