Top of the Pops

First, some housekeeping: I’ll be off tomorrow and Monday for a long weekend planned awhile back with my partner. Afterwards, I’ll be going at the regular schedule until the 22nd when I’m off for Christmas up north. I’ll then be back at it after New Year’s. Also, my Twitter account has been suspended quite randomly — waiting to hear what exactly tweeting partial defenses of Lloyd Austin suggested under Twitter’s rules — so if you could share on social media, that’d be much appreciated. Due to some house repair work today dealing with an old boiler, aging pipes, and the joys of limescale in Central London, today’s column is shorter and more slapdash than usual. My apologies.

Gazprom Neft is reportedly launching a 4th well at the Sarqala Field in Kurdistan, which would raise output there from 24,000 bpd to 32,000 bpd. It’s easy to spin this story as part of a narrative of Russia expanding its influence in the region, what with the 2017 equity acquisitions of controlling stakes over export pipelines feeding into Turkey. That’s a remarkably naive way of looking at power and influence, however. On its face, yes, Kurdish authorities have to deal with Russian companies and needed the money they raised from that 2017-2018 spate of deals (including prepayments for Kurdish oil to be shipped to European refineries) and it gives Moscow an avenue to influence decision-making ini Baghdad. But in reality, the entire operation hinges on the United States maintaining its presence in Iraq and just over the border in Syria, where US interests are decidedly opposed to Russia. If the US were to withdraw and major instability in Iraq created physical security risks for production, Russia would have to deploy its own forces, provide support to Kurdish authorities in the event they are stuck fighting militias or resurgent extremist groups, or else rely on other regional players to step up. The trouble, of course, is that once you’ve provided economic support and legitimacy to Iraqi Kurdistan, you’ve taken a clearer stance on Kurdish autonomy than anywhere else in the Middle East (outreach to Kurds in Syria is a slightly different matter). That doesn’t sit well with a lot of other governments, and it’s a needle Moscow threads not out of genius or guile, but simply because the US can be relied upon to backstop its own attempts to curry influence. It’s the great irony of American strategy in the region that it actually provides Russia more opportunity to be seen to be expanding its influence without making it pay the full cost of doing so.

What’s going on?

Daria Godunova has a really good column out for VTimes highlighting the regulatory problems facing investment in the energy sector in Russia. The legal construction of concessions is not the sexiest topic, but it cuts to the heart of the ways in which Russia’s under-government, over-centralization of political power, and sheer size create massive governance challenges that impinge on the flow of investment into the economy. Private firms looking to win contracts to modernize aging plants are negotiating what is effectively a lease — the government is still the owner of the asset at the end of the day — meant to guarantee them earnings based on tariff rates needed to cover economically necessary expenses and investments the state doesn’t make. Private sector bears the risk, in theory it gets enough reward to do so. But every municipal and regional government has a different definition of what that entails as do the companies involved, and that’s before you consider that tariff controls one electricity costs to remote areas where consumers live, no matter how high demand for electricity actually is in those regions, then creates the backdoor inflation problem of raising costs for the state to maintain output levels without passing on too much of the cost to consumers living in, say, remote Siberia. Concessions agreements are therefore hostage to the state’s need to maintain price controls for Russia’s vast interior, the weakness of municipal governments that are not given enough subsidies from the center to better direct investments locally, and the state’s power over property no matter what guarantees are provided. As Godunova argues, there’s no investment boom coming until the institutional arrangements improve.

The latest CBR data dump on the country’s current account shows that the country’s current account surplus has declined 46% year-on-year for Jan.-Nov. The breakdown isn’t pretty:

Green = exports of fuel and resources Blue = imports Orange = non-resource, non-energy exports Black = real exchange rate RUB/USD

In the accounting methodology, non-resource and non-energy exports rose 1.8% and that was all because of gold exports abroad (how it’s not considered a resource export, I don’t know). Imports only fell 6.9% year-on-year for Jan.-Sept. though. Ruble devaluation once again has little to no bearing on the country’s export competitiveness because of credit constraints, lagging efficiency, and a (relative) lack of integration into international supply chains except for select foreign firms trying to sell in Russia or to the CIS using Russia as a base market. Exports are expected to end the year at 77% of their 2019 levels, a current account surplus of $155 billion. It’s very difficult to foresee Russia hitting its export growth targets of $250 billion by 2024 no matter what happens next on non-oil commodity markets.

The Audit Chamber has found that the self-employed tax regime rolled out over the last few years hasn’t proven a popular means of optimizing tax expenses for individual entrepreneurs, freelancers, and the self-employed at large. The issue isn’t that people are exploiting the low tax rates for earnings — 4% for physical entities (i.e. a person) and 6% for legal entities — but rather its reach so far. There are about 1.3 million people legally defined as self-employed across Russia compared to 14.25 million people reportedly working in the informal sector. The biggest problem identified by Vedomosti’s coverage is the current 2.4 million ruble ($32,688) ceiling to be able to claim the tax rate. Those who are self-employed but run a successful business will frequently earn more than that, and their own interests minimizing their tax burden incentivize them to remain in the informal economy and use other means. On the whole, Russia’s expanding its tax base steadily over time. It still has a long way to go trying to reduce the fiscal drain created by the informal sector, and with it a variety of skewed economic outcomes including higher inflation rates that the CBR can never quite tame so long as the informal economy occupies as much as 44% of GDP in some measures (which are all contested and subject to considerable methodological limitations).

It turns out that export growth/trade integration is a double-edged sword. Kommersant’s reporting today on the agricultural sector highlights that Russia’s growth as a wheat exporter is a problem during the current economic crisis because rising world prices given demand for grains wasn’t interrupted by COVID are now pressuring domestic prices at a time when Russians’ spending power is suffering. The National Security Council appears to be talking about the matter, with Nikolai Patrushev pushing for hard export limits to lower domestic prices. Two quick thoughts: those who want to securitize everything in the economy are on course to lower costs in the short-run while lowering investment into production and ceding some of Russia’s external market position in the long-run and there is no resolving this underlying tension. Any export limit will save consumers’ money, but cost the state more in support for the sector. They might want to start thinking about income support for Russians and increasing infrastructure investment to lower delivery costs rather than playing games with their most successful export story the last 5 years.

COVID Status Report

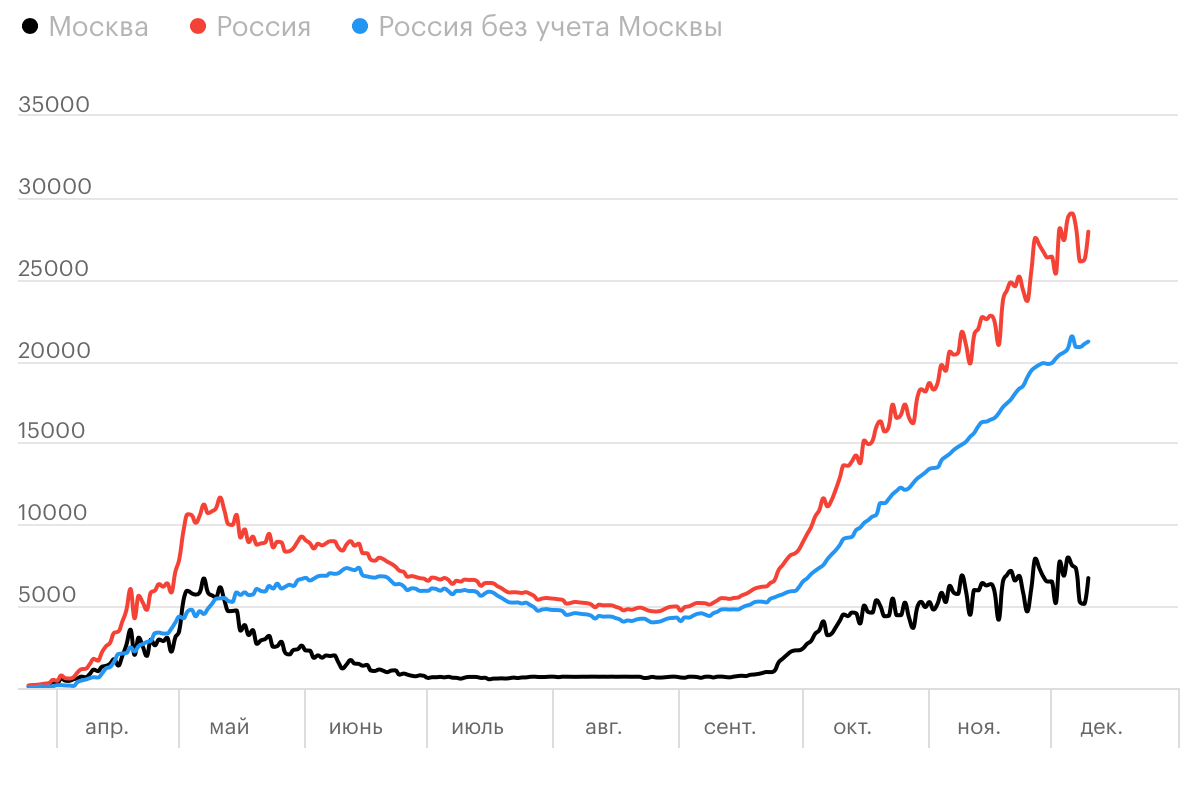

The caseload moved back up past 27,900 with 562 recorded deaths. Absolute numbers continue to climb, but there is a little more evidence of tapering in the data. Regional cases + St. Petersburg are slowly plateauing while Moscow’s stuck in place ping ponging up and down:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

Roughly a third of respondents from polling conducted to gauge public opinion on how bad the situation is for their own regions said they would not trust any vaccine, regardless of where it was made (notably over half of respondents said they’d only trust a Russian vaccine…) and 5.9% of respondents said they’d only trust a foreign vaccine. We might see a photo op with Putin sooner rather than later since the polling showed that a little over 12% of respondents would consider following his example. Those levels of distrust are too high for the penetration levels needed to make the vaccine truly effective at stopping continued infection clusters across Russia. There’s no reason to expect further quarantine measures given the lack of economic support available, but if the public doesn’t get vaccinated at high enough levels because of lingering trust issues — a near 40% ‘no’ rate to getting vaccinated drastically undermines herd immunity — then quarantine measures at the local level might not be going anywhere for a longer time than the Kremlin would like.

Til’ the Money Runs Out

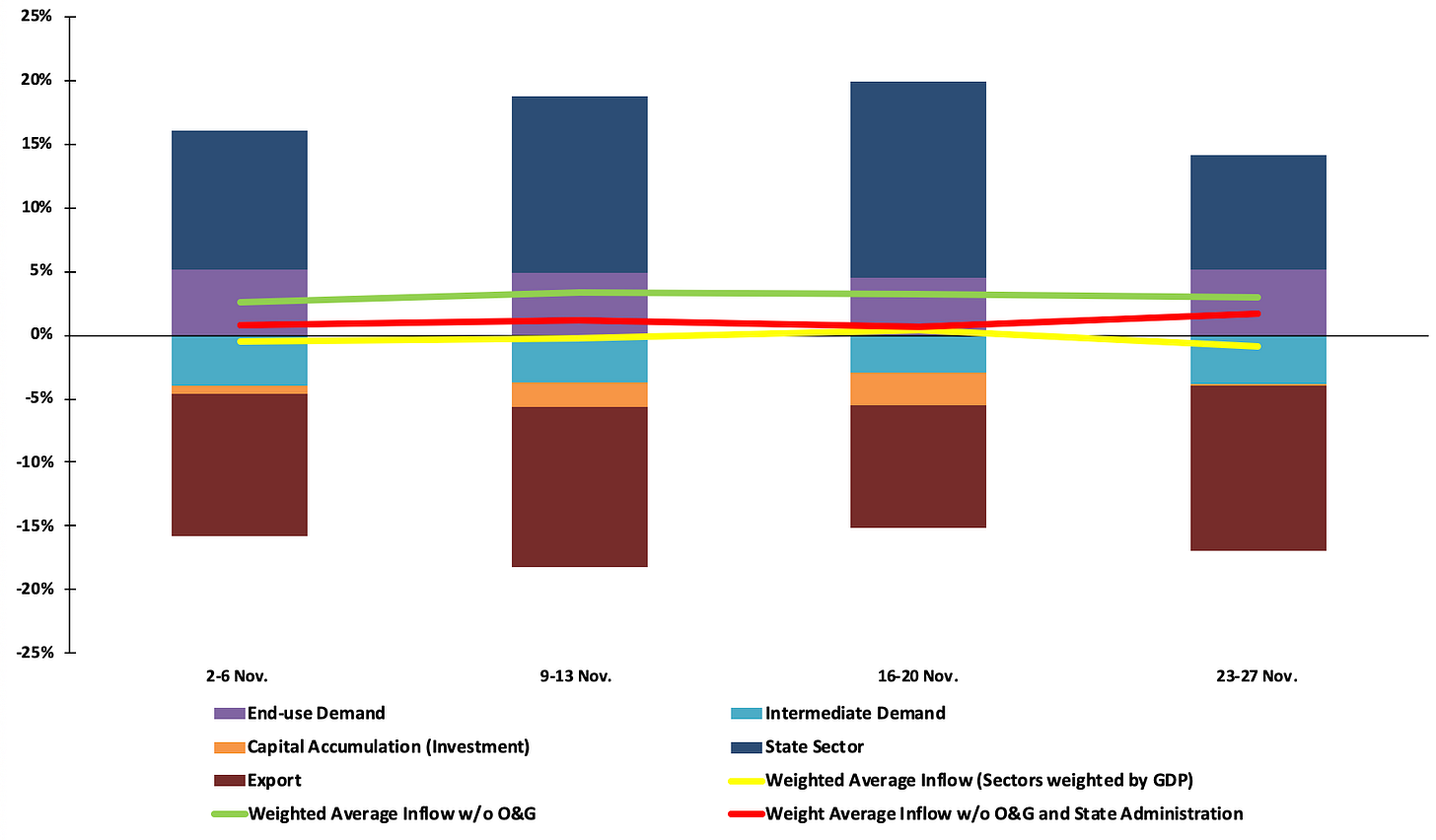

Looking back at the CBR’s review of financial flows at the sector level in the Russian economy from the beginning of December, it’s pretty clear the end of the year is setting up a bad 2021. The following are % changes against “normal” levels from November data:

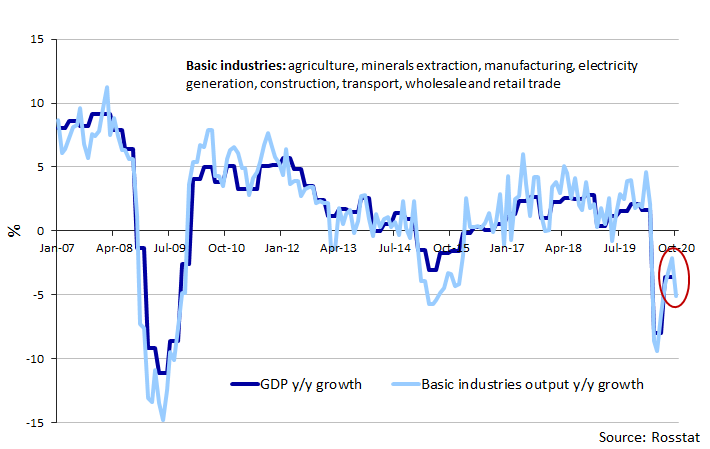

The export sector its seriously struggling to maintain financial inflows at adequate levels, which is feeding into capital accumulation, and intermediate demand i.e. demand between firms and sectors is flagging. State financial flows are a lot higher, but you’d expect them to be even further up in % terms if Moscow had adopted a more comprehensive stimulus plan. This is where the structure of the economy really matters and poses a fundamental problem. It’s exports that do the most individually to drive levels of intermediate demand, whether that’s by supporting Russians’ real incomes or else by ordering more goods and services themselves. The industrial output data for year-end is looking grim:

When you see an output dip at the same time consumer price inflation is becoming a worry, it’s a bad combo. Mishustin is now sounding the alarm in the government that it has to address rising prices for consumer staples since Russians’ real incomes are still falling. Export quotas and tariffs for agricultural goods are part of that plan. But every time they adopt a measure introducing an export inefficiency that reduces the profitability of the firms that have benefited most from counter-sanctions on EU goods, expanded state support, and targeted investments, the more they reduce future financial inflows into investments and intermediate demand from the sector as it begins to lose out on potential earnings in what is effectively a state-mandated deflationary push on business. It works in the short-term, but not for too long. The state response to the issue is still structured by Russia’s simultaneous dependence on external demand and internal market controls. The relative balance of consumer spending hasn’t declined that much in the last 15 years, though the relative cost of foodstuffs vs. goods and services as a share of spending has come down (note that the snapshot Rosstat breakdown for consumer spending doesn’t include spending on housing, utilities, or transportation):

This graph shows a serious policy failure on the part of Russian economic planners. Food should take up a declining share of spending over time with gains in efficiency of production, rising output, etc. That this relative change in balance doesn’t really move after 2013, save a tiny rise in services’ share of spending, suggests both failures of diversification as well as under-investment into productive capacity and efficiency at play. There’s a big gap between inflation for staples over the last decade compared to net consumer inflation including services and other goods:

Food costs about 25% overall coming into 2020 than it did in 2010. Price inflation overall, however, seems to have converged coming into 2020. That supports my own assumption that real income deflation is the primary culprit, but I also suspect that Russia’s export problem going forward is at play too. Mishustin’s trapped by the perverse incentives of the Russian economic system and orders from the boss to tamp down any public discontent. Deflation is preferable to inflation structurally. policy interventions into prices end up constraining growth and investment, and therefore kill income growth. There’ll only be a recovery in intermediate demand and its related financial flows if Russian consumers can afford to buy Russian-made products (assuming they can’t afford imports). Intermediate demand is the turnkey for Russian recovery since its relies on and provides domestic demand. 4Q will end up being brutal for both given the current COVID wave. The slight easing of OPEC+ cuts is the only stimulus I see in the near-term to underpin a more sustainable recovery path.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).