In the Green Zone

A bunker mentality may push Russia to copy China's green financial institutions

Top of the Pops

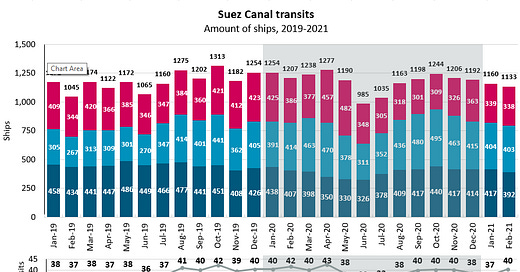

Well, now it seems the Suez blockage might last longer than a few days. No, it’s not striking a blow against globalization and it’s impact will still be relatively short in market terms, but the scale of commerce headed through the canal — worth $400 million an hour — is immense:

When we consider the sheer number of containers or else oil & gas per ship, this is a big short-run hit for consumers and spike for insurance and freight rates. The knock-on effect falls onto the container market since there’ve been global shortages of containers for exporters that have contributed to producer price inflation and trickle into consumer prices. This problem’s already hit Russian auto imports, for instance, and has affected price levels for consumer good imports in Russia a bit. Oil prices keep trending back downwards, even with this disruption, but the ruble devaluation post-COVID shock has left the oil price in rubles far higher than it’s usually been since 2015 despite oil trading about $20 a barrel lower than it did for several months in 3-4Q 2018:

The production cuts are dragging down revenues significantly, not just suppressing intermediate demand in the Russian economy. One imagines that there’d be more pressure to increase output after the next OPEC+ meeting. The current blockage might last a lot longer than the initial few days a lot of coverage assumed. Either way, it’s going to hurt Russia more than it helps based on how it affects trade and prices so long as oil production is restrained and the oil price doesn’t react to the shift in crude flows, something I think will be easier to stomach since European demand is now falling again with renewed waves of the virus.

What’s going on?

The ongoing maneuvering over an income tax hike for wealthy Russians has been met with expected skepticism from many economists — Russian Grinberg, head of RAN’s Economic Institute, calls the proposed hike from 13% to 15% one of an ‘imitative character’ for the elections and little more. Experts at RAN modeled a scenario in which setting rates at 20%, 25%, or 31% for the richest Russians could add an additional 1.3-3.3% annual GDP growth if that money was reinvested into infrastructure and other sorely needed economic activity. The Liberal Democrats have performatively called the bluff on the 15% hike proposal by introducing their own version whereby anyone earning under the living wage (17,000 rubles a month) would not pay income tax with an increasingly progressive scale such that anyone earning 100 million rubles annually would pay 35%. It’s got no realistic chance to pass, but looks great for electioneering. The obvious problem introducing a tax hike on higher earners now is that they’re holding up the consumer economy and without growth, it’d likely suck money out of consumption. This would be most readily alleviated if the state increased spending levels alongside this change. The RAN study that’s being pushed now shows that an increase alongside higher spending would get the economy operating closer to its true potential instead of a stagnant 1.8% GDP growth rate over the next 5 years with a % breakdown by components:

Left/Right: GDP growth (inertia scenario), household consumption, state consumption, fixed capital formation, exports, imports, GDP growth using full potential

The biggest proposal on the market side is using the tax increase to raise the wages of state employees, thus pressuring wages upwards in the private sector and expanding consumption and improving spending power for those who are poorest on the labor market. The KPRF also frequently tosses out ideas about progressive tax schema, but Putin’s decision to tweak the code this year with that hike to 15% for earners at or above 5 million rubles a year has cracked open the door to rewrite the compromise Kudrin masterminded at a time when the administrative capacity to tax was much, much weaker. Mishustin’s success at the Federal Tax Service has, ironically, created greater potential among systemic actors to agitate for further change that could be politically disruptive, particularly since Putin’s only asked the Duma to consider changing the tax code for business so far this year.

The Audit Chamber found that federal programs intended to aid the development of rural areas and villages in Russia were inadequately funded, echoing concerns that MinSel’khoz has raised repeatedly in an attempt to expand its delegated authority. The current plan calls for 1.5 trillion rubles ($19.76 billion) in spending through 2025, of which 730 billion rubles ($9.6 billion) would be federal money. But even this seemingly high spending target comes after a large reduction from the initial 2018 proposal and the ministry has repeatedly explained that it can’t reach the targets set by national goals or other policy initiatives without more money. Some of the trouble is administrative — in the same vein as Mishustin’s centralization efforts, too many parts of policy implementation have been assigned to regional and federal offices that don’t properly communicate, share data or information, etc. The bigger issue here, in my view, is the consequence of underinvestment in the poorest parts of Russia at a time when a majority of Russians under the age of 40 would not like to see Putin remain in power past 2024 per Levada polling (accepting the usual caveats about what polls in Russia actually tell you):

Green = would like him to stay on Black = wouldn’t like Orange = hard to say

The ‘fight for the future’ among younger Russians in the biggest cities has already been lost, at least in terms of the assumed legitimacy of the regime — there’s little reason, however, to equate that to political power for the non-systemic opposition at the national level (yet), rather than what I think is closer to political influence. But the further that rural areas and villages fall behind and people live first change they get to pursue what jobs are available in cities, the harder it is to maintain the coalition of older voters/pensioners, workers in industrial cities, and regional-rural turnout that has delivered for the regime since the 2011-2012 protests.

The national LNG strategy through 2035 calls for Gazprom to build LNG trains linked to the Tambei cluster on the Yamal peninsula with a capacity of 20 million tons a year, but experts doubt the project will be built to that capacity. The trains alone could cost $20-25 billion, a figure that rises to $35 billion if you include building necessary infrastructure (Gazprom won’t want to rely on Novatek’s assets at Sabetta port without something of its own), and as high as $40-50 billion if you include building petrochemical refining plant capacity. Building up LNG capacity is effectively creating a redundancy for the Tambei cluster since it’s already hooked up to pipelines in hopes that the market for LNG will be large enough to accommodate rising Russian export volumes. It seems that the proposal as is primarily address pressure in Moscow to meet the development target and create domestic demand for goods and services rather than a rational economic calculation on the part of Gazprom. No one at MinEnergo nor Novak seem concerned with the problem of volumes of piped Russian gas competing with LNG, further weakening Russia’s pricing power on European markets in particular, but increasingly in China as well. Despite already being awash in reserves, Gazprom is now exploring once more in the Barents Sea past the Shtokman field, which ended up going nowhere as a project. Miller will keep promising to improve the governance of Gazprom, but it’s not acting like a company focused on profit maximization or with a long-term vision for how to secure better return and/or market share. It’s just trying to head off Novatek before losing more ground as its LNG rival keeps expanding production capacity and closing deals with foreign firms.

The fishing industry is appealing to both the Duma and Federation Council to review and change a bill passed on second reading that mandates a transition to electronic trading after agreeing to usage with local owners of distribution (fishing) sites where ‘bioresources’ i.e. wildlife such as fish are caught for commercial activity. The reason is that, per the industry, the legislation passed does not allow for existing contracts not based off the new electronic system to be rolled over the onto electronic platforms, creating an opening for the businesses best prepared logistically to make this change to steal lots of business in a sector that’s generally barely getting by and took a big hit in the last year due to Chinese restrictions on Russian fish imports. The original bill protected them. The bill would reportedly affect 7,600 fishing sites producing 750,000 tons of catch, half of which is salmon — all told the contracts affected are worth 60-65 billion rubles ($790.8-856.7 million). Further, the current bill doesn’t provide any compensation if a firm sank money into local infrastructure but then loses its contracts from the change. Roughly 70% of Russia’s fish is produced in the Far East and with food prices climbing and climbing, the last thing Moscow needs is to anger an important industry for a massive region with a disruption that would likely be noticed by consumers, at least in the short-term since contracts renegotiated during a period of noticeably rising prices are likelier to push prices further upwards than existing contracts negotiated, with some amendments, prior or earlier on in the current surge of inflation.

COVID Status Report

9,221 new cases were recorded alongside 393 reported deaths. There’s still signs of concern. St. Petersburg just extended the ban on nightclubs operating till the end of April, but has slackened rules around wedding gatherings (not that these restrictions are proving particularly effective…). Valentina Matvienko of the Federation Council offered a more critical note that restrictions across Russia could only be ended in total if a majority of people are vaccinated. The sense you get from the messaging is that the government’s well aware another wave might blow up in its face, but has so catastrophically wasted any credibility on the public health response that all it can do is rather weakly turn to moral suasion, as if Russians are particularly concerned with what Matvienko’s saying. Most of that work is happening at the local and regional level. MinZdrav is rather comically assuring people that there’s no evidence of any effect from the vaccine on people’s “reproductive functions.” One wonders why the hell they needed to issue that statement. Rospotrebnadzor just confirmed that the EpiVacKorona vaccine is effective. You can sense quiet desperation to get more jabs in arms, but there’s not much they can do. The damage from the lackadaisical response last year and early this year has been done.

Not so pretty green

Thanks to Maria Shagina’s Twitter feed and kind help passing along two reports, I stumbled upon a new release from the Skolkovo Energy Centre on decarbonization and the oil & gas sector. First off, I was mildly surprised by how well Rosneft and Gazprom made out for emissions levels vs. IOC peers:

Gazprom is presumably worse because of the scale of flaring and its disastrous handling of investment and construction at projects like the Chayanda field. Rosneft’s performance surprised me a great deal more, and probably reflects the nature of its production base. I’d caveat the data available for oil — this RFERL writeup on oil theft is fantastic and a great reminder of how poor the institutional environment to track the relevant data likely is, though I’m not dismissing Rosneft’s relative performance. I do wonder how BP’s stake in the company affects its own figures, however. In terms of carbon intensity, the two main national champions aren’t too bad all told. I do wonder if Rosneft risks worsening its performance with a large expansion at Vostok Oil, where the conditions are a lot worse for monetization of emissions and related mechanisms to reduce that figure. Financing seems to be where the rubber meets the road, and also reflects the broader structural challenge Russian policymakers face managing the influence and impact of foreign regulatory and trade policy choices on domestic industries. The following breaks down sources of debt financing:

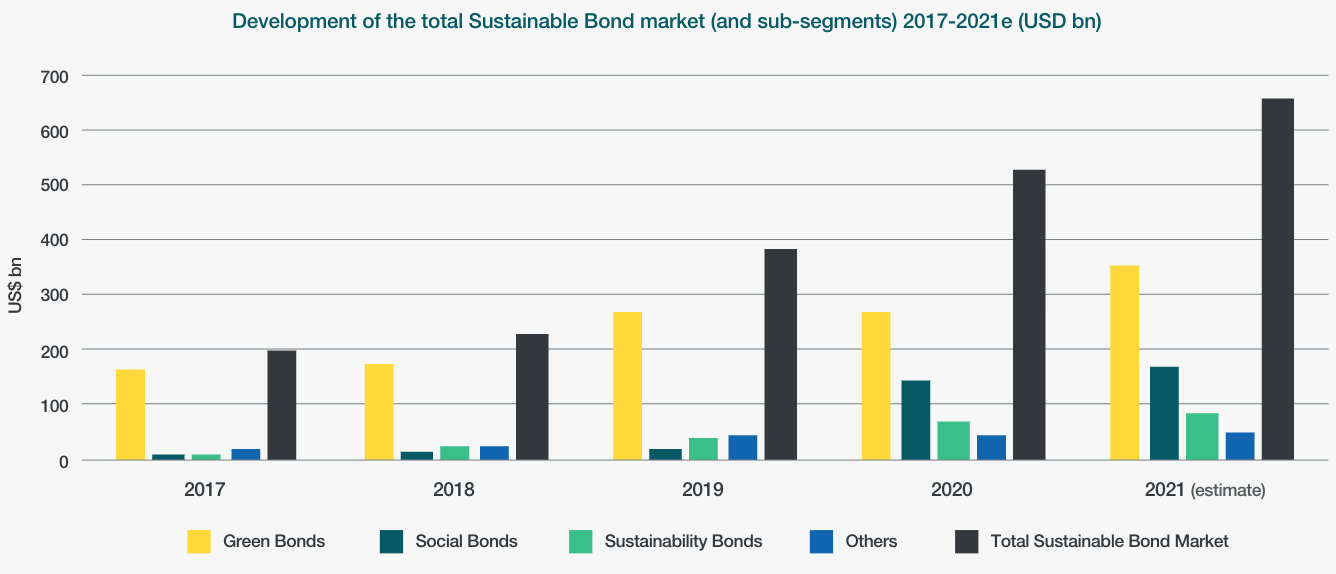

The sector holds more debt in the form of Eurobonds and international credits and loans than in ruble-denominated credits and loans domestically. It makes sense. If they’re selling their products in dollars and Euros (or yuan), it makes sense to tap more liquid foreign markets with lower borrowing rates, especially if you’re importing large orders of dollar/euro-denominated imports of goods and services. That’s often the case for major oil & gas projects at some point of the supply chain or project execution. Currency risks matter a great deal and borrowing preferences therefore partially correspond to the state of import substitution for the sector since more stable foreign currencies with differentially lower inflation rates can purchase more domestic goods and services as well, setting aside as well the role that oil & gas companies play in accumulating foreign currency through sales and financing to help manage both the current and capital accounts. If lending requirements for fossil fuel companies tighten as the demands to ‘green’ finance deepen, that would put considerable pressure on Russian corporate practices and the domestic financial sector as carbon trade adjustment take effect. It’s a matter of economic gravity. If the state won’t expand deficits to finance green projects directly and the Russian banking sector’s stability hinges on more hawkish Central Bank policy, borrowing abroad where rates are being held down by central banks is all the more attractive. Consider the scale of the sustainable bond market — and note that it was only recently that China excluded clean coal from its own green offerings, so that the Chinese market will become more attractive for foreign investors as well:

Total issuances for green bonds finally passed $1 trillion cumulatively since 2007. Some 2021 forecasts put green bond issuances closer to $500 billion for the year. The basic problem for Russian corporates is that we’re likely to see the slow, but steady evolution of carbon risk premiums on loans. One study using European companies from 2011-2017 for the underlying dataset found that lower carbon profiles for European corporates reduced the cost of credit by 16-100 basis points. That’s not a huge difference, but given the progress since then and likelihood of regulatory regimes formally including carbon pricing mechanisms for credit as well as requiring increasingly transparent and complete corporate accounts of emissions levels, you’d expect the relative discount that can be realized by greener companies in Europe to have grown since (or at least be closer to growing now). Europe is really the market to watch on that front since it’s where Russian firms do most of their dollar and Euro-denominated borrowing. For Rosneft in particular, the cost of credit matters a great deal given Sechin’s debt-driven acquisition obsession and the fact that the company’s increase in earnings since 2014 has almost always been paralleled by increasing debt — lest we forget that by spring 2018, the company was spending the equivalent of over a third of its 2017 earnings on debt servicing payments.

But based off the Skolkovo report and the newly minted VEB.RF taxonomy for green projects in the Russian Federation, it’s important to note that the push for ‘green’ everything in Russia faces limited political pressures domestically and appears to be following China’s lead instead. It shouldn’t be controversial to assume that if a Russian project mandates a 100% recycled material target for a project or some similar measures for inputs intended to create low emission infrastructure, there will be state procurements doled out to the well-connected for those contracts. The reduced level of competition then creates additional cost since inefficiencies are fostered by state policy. There’s probably an implicit understanding that the role of the state in guiding economic activity in China is more useful to learn from.

China’s own green finance market is itself reflective of the state’s use of debt instruments to maintain GDP growth targets irrespective of whether or not said growth is healthy and, generally speaking, entails rising levels of emissions and externalities for little economic gain. This is true of the real estate bubble and many high-speed rail routes, green energy investments aside. Some of the mirroring may also end up being political — Xinjiang is one of China’s green finance zones i.e. regions with pilot green financing initiatives to deploy green bonds and related instruments to finance regional economic targets. China’s likelier to provide some clarity on practices developing a market in conditions where external actors may sanction banks or firms doing the borrowing as well as one that provides some useful parallels for future green financing initiatives in Crimea. Should future sanctions or reputation risks cut off Russian corporate access to green financial instruments in Europe, regulatory alignment with China makes more sense politically despite posing its own set of challenges whose significance the regime doesn’t seem to fully grasp. Marginal changes in the cost of credit from the West will spur changes in Russian corporate behavior, but it’s likely that China’s development path for its own green financial institutions will more readily inform whatever policies are adopted in Moscow for domestic purposes. European entreaties to cooperate on climate issues should take note.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).