Top of the Pops

I was going to write up a response to Biden’s planned foreign policy address for the US ‘newsletter’ yesterday, but it was postponed due to the weather. Hopefully it happens in the next few days. It’s a convenient hook to dig into Biden’s first major statement to the public on foreign policy and check it against what his administration’s initial moves show. Also, a brief aside. Check out this fantastic piece from Temur Umarov on Sadyr Japarov in Kyrgyzstan for a look at how the proto-nationalism many expect to emerge is tied up in Chinese financial interests in Kyrgyzstan and outright financial support for his campaign. The question of course remains how the public and other elites respond in time. I think another open question is how running ‘against China’ is a useful tool to win power and try to extract leverage, or else force Chinese firms to use more offshore intermediaries to hide where the money comes from. But Beijing’s shift to direct support for elites is surely going to rattle any sense of a Sino-Russian ‘condominium’ in Central Asia, something I didn’t dive into much in recent years as I shifted my focus more to energy but never believed for the simple reason that China evidently does not view Russia as an equal power because it is not and the personal relationship between Putin and Xi does not define most of the relationship.

Producer restraint and cold weather are pushing up oil prices further as Brent crude is now trading at or above $57 a barrel. There’s evidence of demand picking up pace in Brazil, the world’s 7th largest oil consumer:

The market is clearly on pace to tighten through till summer, but the question remaining is just how much drillers in the US and the mid-sized firms leading offshore developments elsewhere, including Exxon and Petronas’ work in Guyana-Suriname, react to prices sticking higher. If oil sells at or above $50 a barrel for 2021, then US shale drillers will see a roughly 33% increase in cashflow generated from operations after yet another round of cost cutting. Investors aren’t buying it so far and Middle Eastern producers seem skeptical that shale poses the same threat in the longer-term, but while everyone hopes shale drillers keep to their word that they won’t drill recklessly, all it takes is a slightly higher price and a new bout of Wall Street mania that this time is really different to change the dynamic. I'd watch to see how US banks react in the next month or two.

What’s going on?

Gazprom achieved record export levels in January selling a combined 19.4 bcm to countries outside the CIS, a 45.9% increase year-on-year. A colder winter in Europe and Asia boosted demand, and while Gazprom realized higher earnings off of rising spot prices, oil-indexed or mixed-index contracted deliveries with a months-long time lag didn’t benefit as much on the price front so that the calculation that it’d rake in $4.5 billion at current spot prices doesn’t reflect its actual gains. The episode has reinforced that Gazprom is a ‘swing producer’ for European and now Chinese demand since no one else is able to ramp up deliveries if needed so quickly. But at the same time the changing underlying structure of the market strengthens Gazprom’s role as a supply side manager i.e. it can hold spot prices in Europe by withholding export volumes, that changing market structure — and structurally warming winter seasons — means it will primarily play this role in ‘surges’ in the future. The EU is already beginning to struggle with blackout risks because of the penetration of renewable energy and declining conventional power capacity. That’s bullish for natural gas prices since they’ll have to command a higher end price to maintain capacity that’s not used as frequently. But the European Commission is pushing hydrogen come hell or high water (well, the latter is coming . . .) and there’s growing interest in pursuing small, modular nuclear reactor tech in parts of Europe to try and marry the stability of nuclear power with decentralization and appropriate scale. In short, Gazprom better get while it’s good cause everyone’ throwing everything at the wall to see what sticks.

After 4 years of (relative) fiscal consolidation at the regional level, COVID has sent regional debt levels back into growth bigly. As of the 1st of January, regional debt was 18% higher year-on-year. The following is measured in billions of rubles:

Orange = state securities (bonds) Green-Beige = bank loans Blue-Purple = lending via the federal budget Pink = state guarantees Black = other

Regions now collectively owe 2.5 trillion rubles ($33 billion) as they negotiate yet another round of Federal fiscal consolidation that, at least compared to past iterations, has left MinFin far more willing to expand budgetary support measures to regional governments tasked with a wide array of underfunded or unfunded mandates from the center. The looming issue this year comes around summer when bank loans taken out per anti-crisis measure conditions have to be paid back or else restructured. That’s likely to be around when MinFin plies more pressure on regional governments ahead of the September elections — and when the governors and regional parties haggle for support to deliver the results the presidential administration would like to see. Either way, the relative debt low is still about 9.2% lower than it was in 2014-2015 during the last oil shock.

The estimates that GDP only contracted by 3.1% have set off speculation about how it is that the Russian economy beat expectations so soundly for 2020. There’s just one problem: it actually didn’t. End demand for consumers/households declined 8.6%, savings took a hit, and the stagnation linked to the budgets over-sized role in setting the business cycle for manufacturing alongside a fundamentally weak services sector hid the extent of the damage. Never mind that Rosstat slightly changed its methodology as usual to hide the damage, the bigger issue is that while manufacturing staved off a worse result for the year in 4Q, all evidence now suggests yet another slowdown during recovery. Some are now trying to argue that the economy’s growth capacity is closer to 2% annually than 1.5%, but that seems far-fetched. Value-added household activity for work and production of goods and services fell a whopping 26% for 2020. Future growth requires a higher share of SMEs, more higher-end services jobs, etc. None of that is borne out by the data. Rather Russia got lucky in 2020. It won’t be this year.

Missed this yesterday, but the rising shipping costs between the US and China due to a squeeze on demand for Chinese exports has affected import costs for Russian firms and consumers. Per data from INFO-Line Analysis, prices for imported home appliances, furniture, and home products might rise as much as 10-15% because of the current shipping rate hikes. To visualize the shift, note that coming into 2020, average costs per container shipped were around $1,500 and by year end, that had risen to $9,000. In RBK’s reporting, they note that a price increase at that scale means that if you pack 60-70 refrigerators in a 20 ft. container unit, you have to raise the price by over $100 for each refrigerator if you want to maintain your profit margin. Import prices in January for Russia actually appeared to decline against December, but a likelier culprit is simply weak Russian demand and a weaker link between shipping container costs by sea and anything hauled over the Chinese or Kazak borders by truck or rail freight. It’s still an inflation risk, and a great example of how Russian economic policy really can’t control external inflationary factors when they arise.

COVID Status Report

New cases fell further to 16,643 for the last 24 hours and deaths came in at 539. Moscow’s made considerable progress getting the virus under control while St. Petersburg lags and the regional make up of the worst hit hotspots has shifted a bit. These are case per 1,000 people:

Pskov, Murmansk, Novgorod, Kalmykia, and Karelia are all ahead of Moscow though trailing SPB by a significant margin. On the whole, there are signs that the strain at the regional level on healthcare systems appears is unevenly abating — whereas some are able to build up reserves of cots and more fo COVID patients, others like Tomsk have had to refuse care to COVID patients on a short-term basis to disinfect facilities on a tight turnaround. There also appears to be an undercurrent of resentment from some that the economy appears to have come out of COVID-19 in alright shape, but incomes fell whereas the opposite happened in the West. Though the situation is improving on the whole fairly steadily, you get the sense that the reportage is still a bit skewed. The Duma is now considering supporting ‘vaccine tourism’ in a transparent soft power ploy to bump up tourism earnings. That suggests that internally, at least, the conversation has already moved on from managing the domestic problem.

States of Mania

The fervor over the war between Wall Street hedge funds and Reddit freedom fighters has prompted a new wave of introspection over just how irrational and insolvent funds and people can be while banks always win in the end. It looks like a set of hedge funds, including Andurand Capital Management — famous for betting huge on negative oil prices during the initial COVID/price war market shock to win back investor confidence — are now predicting a massive increase in EU carbon prices. This gets really interesting because speculative positions among hedge funds and investment banks can end up swaying real world prices and policy decisions, something that Russia and its scorn for financialized global capitalism written into its own security strategy documents would do well to learn from given that its now affecting future hydrocarbon consumption. Mind you I’m still learning this stuff as I go, but a basic overview of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) — a cap and trade system — is in order.

The ETS establishes a system of emissions allowances per emissions reduction targets set by the European Commission that are allotted to EU members against caps on total emissions levels on the following basis as of 2021:

90% are given out based on verified emissions from 2005-2007

10% are given out to the least wealthy member states with the greatest needs for power grid modernization etc.

The state then auctions off the allowance broken down into allocations by sector, with companies within each sector then bidding on the emissions allowance available. While international credits used to be applicable, whereby companies could use efforts to offset and/or reduce emissions on third-markets — generally developing economies — to meet their EU targets, the domestic reduction targets as of 2020 no longer use them. Auctions are also not universally deployed. They were first implemented for the power sector since wholesale electricity trades are conducted using auction systems, and have only been phased in for other sectors slowly with free allowances made depending on the rate of the transition for the sector in question. These allowances have been reduced each year to force more compliance, more reductions, and stimulate more investment into emissions reducing activity and technology. As of 2020, 57% of emissions allowances were sold at auction with the rest given freely. Caps on emissions are steadily reduced at the national and sector levels to incentivize further reductions and support prices.

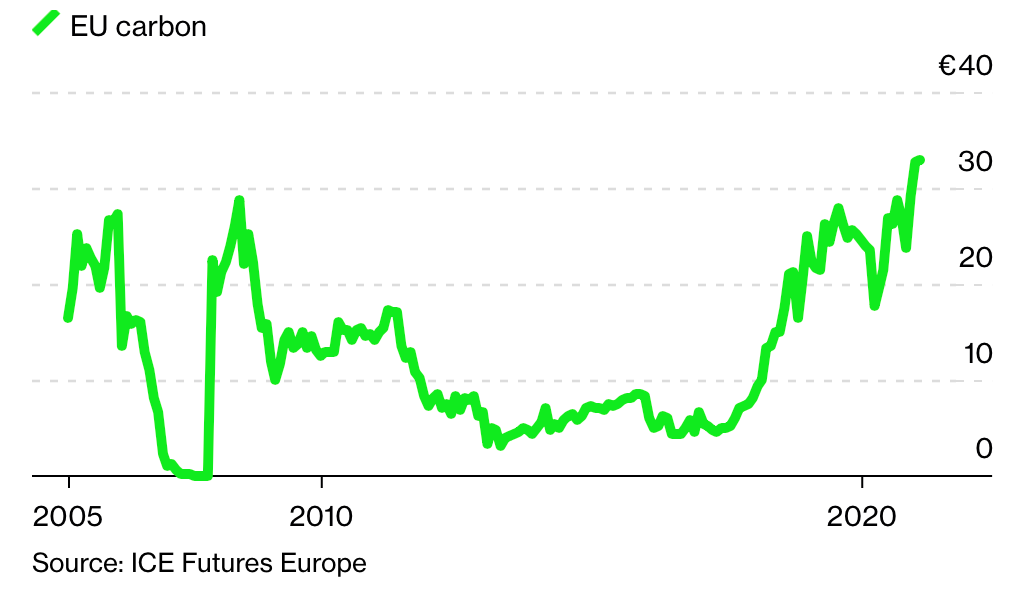

Setting aside the complexities of how the funds raised by the system are used — frankly, the EU doesn’t seem to be particularly good at redeploying the capital raised for maximal gain because of core Eurozone members’ economic imbalances and under-investment into R&D/real productivity gains — its real problem is instability. Since 2009 and the knock on EU economic activity caused by its mismanagement of the Eurozone crisis and a decade of austerity politics, there’s been a surplus of allowances that have actually depressed carbon prices and created market instability. Take ICE Futures from the London carbon market:

The result has been a relatively ineffective instrument to spur change until the cap reductions and other regulatory pressures from member states ramped up prices despite weak economic growth. Basically, the program would have been a lot more effective had underlying economic growth been stronger and demand for those allowances greater. Andurand et al are betting on carbon prices skyrocketing to as high as €100 per ton as the Market Stability Reserve within the EU ETS has stepped up the withdrawal of surplus credits since 2019 to support prices. The real driver for further increases has to come from outside the power sector, and that’s where hedge fund speculation and market distortions are a really big deal.

Take Tesla. It’s been able to drive up its profits by selling emissions credits to other automakers:

As carbon prices rise, Tesla benefits within the EU the more it can sell its surplus credits, in line with the intentions of the scheme. But it’s also allowed Tesla, a company that is not profitable, to stay in business and keep pushing the envelope of its tech until it can achieve sustainable business viability. It’s an approach that can’t work if everyone does it, but still prompts a race to emissions reductions whenever regulations impose additional marginal costs for a failure to do so and has given Tesla a leg up financially on what’s otherwise an at-risk business model. First-mover advantages abound for the companies able to rapidly deploy and scale new technologies while minimizing their carbon footprints as they figure out how to game various support mechanisms between developed economies.

It gets weirder when thinking about where commodities are headed. Oil producer Occidental joined up with Macquarie to sell the world’s first carbon neutral oil shipment to India, expanding off existing efforts to sell carbon neutral LNG. Imagine the impact once carbon adjustment costs are imposed on imports and the corollary effect on futures markets. Suddenly you have a bifurcated oil or LNG market whereby the relative costs of ‘dirty’ vs. carbon neutral shipments could lead to the creation of new futures contracts once the market’s liquid enough, thus accelerating hedge funds, institutional investors, everyone taking positions and providing liquidity to reduce transaction costs for carbon neutral cargoes.

The biggest problem for Andurandet al’s bet is that it hinges heavily on policy variables. But market forces matter too. If natural gas prices do rise, as many expect, then the marginal costs of emissions matter more and more since the power sector is the most thoroughly enmeshed in the trading scheme, which would drive down prices unless the Market Stability Reserve steps up. And electricity needs are going to rise with the displacement of ICE vehicles with EVs. But the IEA still forecasts a net decline in energy demand in the EU by 2030, with gas stagnating at current levels (until tech changes the mix):

And there’s little reason to expect a strong European recovery given inadequate stimulus and investment plans. So really the hedge funds are betting that policymakers get more aggressive very quickly. The irony, of course, is that by taking large positions, they make it easier for policymakers to do just that as investors start planning for the contingency as they figure ‘hey, they probably know something I don’t’ or else ‘hey, I can beat these guys.’

What’s even more important now is that China has just launched its own emissions trading scheme, sure to overtake the EU in size, scope, and global impact over time. It comes just as Chinese banks and financial institutions have begun to collaborate more with US banks and institutions on futures markets. Carbon is a growing futures market for spot, spread, and derivative trades, a new frontier for speculation that will swiftly impact the expectations of energy companies, investors, and policymakers alike. If one conceives of the EU’s Market Stability Reserve as a sort of central carbon bank maintaining an adequate price floor and, perhaps, the creation of a public financial institution that takes part in mediating the value of emissions-based financial assets — recall the Bank of Japan’s massive expansions into ETFs and securities this last year — then there’s every reason to believe that Andurand’s one-way bet on carbon makes sense. Financial markets are swiftly adapting to a post-COVID reality in which the energy transition can be monetized even if profit margins for green energy are lower than their hydrocarbon counterparts. Russia’s in an unenviable position of relying on two trade partners/blocs that are accelerating the development of carbon markets in a manner that will, eventually, allow for seamless global trades between countries and regions and the use of policy instruments and institutions to keep driving the cost of carbon upwards, guaranteeing stable returns (if done right). The world’s proto-nationalist/mercantilist turn has covered trade far more than finance, and that doesn’t seem to be changing for now. That should really scare the Kremlin the longer it holds off on a domestic carbon tax or carbon trading scheme.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).