Top of the Pops

Elvira Nabiullina and the Central Bank have shifted completely into hawk mode, now preparing the market for a 1% key rate hike in July to 6.5%. It’ll be the largest month-on-month hike since they massively raised the rate to stanch capital outflows at the end of 2014 as they were floating the ruble. And it’s going to climb from there. I personally don’t see how they can stop at 7% based on the current dynamics, but it’s a little too soon to tell. Oil prices are an important variable and now present more downside risks than growth potential for the Russian economy. Look at the CBR’s June inflation release from the perspective of producer goods and services prices:

The direction of travel for everything except end purchase prices (lately) is up. And the overall shape of inflation for producers matches the surge last seen in late 2018 when oil prices climbed above $80 a barrel after the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on Iranian oil exports. As oil prices trend higher — not forever, mind you, since the easing of cuts will bring them down again — some of those same pressures are re-appearing on top of the broad-based commodity price increase. Services costs won’t rise indefinitely without sustained demand, but insofar as a great deal of services demand clusters to serve extractive industries and financial services, these price increases are going to hurt. If the economy recovers its COVID losses by the end of the year, it’ll an imbalanced and unhealthy recovery.

What’s going on?

Successful tax collection and administrative reforms keep rolling — from July 1, the minimum level of income, assets, and tax obligations required for businesses to be hooked up to the Federal Tax Service’s (FNS) electronic monitoring system will be slashed by 2/3rds. That’s 3 billion rubles ($41.41 million) to 1 billion rubles ($13.8 million) for income/assets and 300 million rubles ($4.14 million) to 100 million rubles ($1.38 million) for tax and social obligations. Non-oil & gas taxation is likely to keep rising as the FNS, led by Mishustin when the current system was launched, is doing a very good job of bringing more activity out of the grey economy and taxing activity. The latest reform is well-timed since the pandemic forced lots of firms to shift to more remote forms of work and, most importantly, created massive headaches to be able to access programs intended to help SMEs since smaller firms had to make sure they could adequately report their income and tax levels. The crisis has incentivized an expansion of the state’s tax oversight apparatus to make sure that future relief or stimulus efforts can be better targeted. It’s remarkable to see just how efficient and well-managed the tax service continues to be, surrounded by ministries and agencies overrun by political entrepreneurs and frequently incoherent policy frameworks that undermine their ability to make use of the pools of human capital and experience that still exist across the Russian state. But it also reveals the political priorities of these institutions. While I wouldn’t describe the FNS as an ‘extractive’ institution, its chief aim is to resolve the problem of oil & gas dependence to the extent possible by broadening and deepening the tax base so that the regime can better mobilize the public’s wealth to achieve targeted political goals like poverty relief, sustain defense spending, and create new sources of investment and state support. In that pursuit, the tax service has been quite successful.

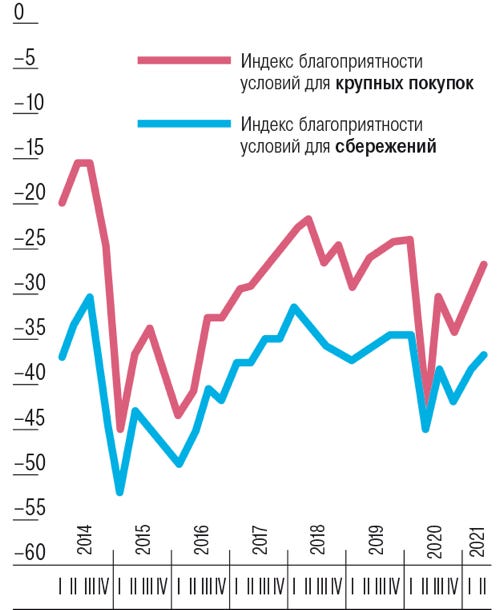

Rosstat surveys show that despite a small bounce back from 1-2Q this year when the COVID case load was lower, momentum for improving expectations about the economy and one’s finances have basically stalled since. Setting aside that expectations indicators have been negative for consumers for over a decade, they also parallel a degree of pessimism among businesses. Things may have gotten better from their worst, but the improvement won’t last. The following comes from the Rosstat survey assessing current economic conditions:

Red = index for large purchases Blue = index for savings

People are spending again, but that can have negative drivers — fear of future price increases that would put something out of reach, for example — and the savings context hasn’t shifted that much. 51% of respondents say it’s better to save than spend right now and the indicators suggest household finances are worsening. Anton Siluanov’s rhetoric about economic policy shows that attempts to increase real incomes are really focused on reducing absolute privation and poverty rather than lifting all boats. There isn’t a compelling view of how to create conditions to achieve a wide range of goals without spending more. If the thinking is more supply-side stimulus measures like tax cuts instead of fiscal policy, it’s difficult to imagine households will see much benefit. Businesses need customers as much as tax breaks or regulatory moratoria can help.

Putin just signed a law passed by the Duma exempting exporters of non-energy non-resource exports according to the EAEU’s customs definitions from requirements to declare their earnings from sales in the West (or elsewhere) on their Russian accounts. In practice, that refers to gold, metals, and grain exporters. The change will take effect on July 1. Gold is the biggest winner — exports rose 160% last year after the government stopped domestic purchases for reserves and liberalized the issuance of export licenses for miners. Banks are keenly interested on the opportunity to speculate on prices. Exports last year reached 320 tons, but only 290 tons were mined in Russia so that gap was made up by banks selling their own reserves on the market to exploit last year’s rising prices over the summer. Export earnings tripled to $18.5 billion on gold alone. Metals — nickel, copper, zinc, and similar resources — earned $35.5 billion for exporters last year. Gold and these metals therefore accounted for about 16.2% of Russia’s exports for 2020. By allowing these firms to park their earnings abroad, the operators and owners get to keep more of their money outside of Russia and away from the state. But it’ll actually reduce the inflow of foreign currency into the economy since the earnings won’t be repatriated, which doesn’t really make much sense from the perspective of the balance of payments and bank sector’s. needs. It risks making the ruble more volatile in response to shocks since banks have to run down their currency reserves to cover external obligations whenever they occur. It’s evident that the domestic lobby managed to win concessions because these resources will matter more in the years ahead for Russian trade, metallurgical firms are already taking the hit for the budget instead of the miners, and because any profitable sector in the Russian economy important to political or geopolitical ends has the heft to make demands in exchange for serving the state. There’s also another aspect of this learned from the Soviet experience — it’s useful to have pots of dollars and Euros stashed in banks abroad for future use.

Transneft has accused Rosneft of delivering it ‘dirty’ oil contaminated with organochlorines that can pose serious problems for refineries processing crude. It’s a re-run of the scandal back in 2019 when contaminated deliveries damaged refineries in Belarus and triggered a hunt for someone to blame as the contamination caused the greatest interruption of supply via the Druzhba oil pipeline in its history. The pipeline monopolist estimates that 350,000 tons of crude have been contaminated via deliveries to the supply point at Mukhanovo where Rosneft is the sole supplier. Igor Sechin’s team acknowledges the contamination but claims it has nothing to do with it, blaming Transneft for failing to adequately maintain its pipelines. The counter-accusation makes little sense to me. There could literally be organochlorines present in cleaning agents used by Transneft, but the likelier culprit is the declining quality of oil extracted from Rosneft’s West Siberian oilfields. Organochlorines are often used to remove wax in oil wells that builds up over time and as part of solutions used by drillers to maintain pressure at oil wells. But crude oil then has to be cleaned of these compounds before being accepted by midstream operators handling shipment via pipelines, trucks, or tankers. What seems likeliest is that both companies are to blame — Rosneft’s coping with oil wells that are depleting and require more and more chemicals and water to maintain well pressure and Transneft didn’t properly check for organochlorine levels when accepting the delivery. In 2019, Transneft’s idea was to take control over the points of delivery for products that were otherwise controlled by the oil companies and set a unified standard for testing while Rosneft wanted to create an independent body that would test crude deliveries. The former made more sense but would have given Transneft too much bargaining power with oil firms. The latter was a stupid waste of money to a third-party that would just create new rents. Neither were really adopted and here we are today. Expect a public photo op to scold someone.

COVID Status Report

20,616 new cases and a pandemic record 652 deaths were recorded in the last day. The costs of the current wave keep mounting. In Moscow, restaurant earnings fell 90% in the first day of the new restrictions and we should expect similar hits elsewhere where businesses aren’t fully closed or being provided new support to stay closed. Aleksandr Gintsburg of the Gameley Institue has warned that the % share of lethal cases is no longer 1-2%, but rising to 5-10% and vaccinations are absolutely necessary. The only comfort we can take from the official data is that the rate of case increases slowed this last week (24.3% vs. 31.5% prior), though from a much higher base. We have no idea how effective the newer restrictions are yet and won’t know until next week if they’ve had an impact:

The government has just taken steps to fight the proliferation of fake vaccination certificates via the Ministry of the Interior. There’s finally open recognition from the Kremlin that the 60% vaccination target for the fall is out of reach. If they can’t vaccinate enough people, the only alternative to deal with a more transmissible variant is to step up longer-term restrictions across the economy. But that would then interrupt the recovery and situation ahead of the September elections. The waffling, indecision, and narrow view of what’s possible will cost an untold number of lives. Rospotrebnadzor has made it clear that the weather is no longer seen as an important factor determining the extent of the spread of the virus. The state has to act in a more decisive and coordinated manner.

Waves of Heat and Inflation

I wanted to reflect on two stories, one Russian and one more global, that are deeply connected but haven’t yet been linked by the disciplinary blinders policymakers in Russia (and the US for that matter) are trapped by. Vedomosti is reporting that the government is now set on establishing a coherent system of policy interventions to prevent global price increases for targeted goods from triggering higher inflation on Russia’s domestic market. Mishustin’s team want to divorce Russia’s inflation indicators from the world economy. There’s some stuff buried in the reporting that’s a decent idea, but it risks doubling some of the internal contradictions to policy we’ve seen exacerbated by the COVID crisis. Note that these are still preliminary and there are lots of details to iron out.

The first half of the new proposals is to build out a price forecasting apparatus within the government that forecasts world prices 8 weeks ahead and their expected impact on domestic price levels. Beyond prices, the apparatus would then assess Russian consumers’ access to these goods. Andrei Belousov is leading the effort with the leaks to the press indicating a desire to utilize market mechanisms to head off supply risks. Though it’s never spelled out here, what would make more sense here would be a formal commitment to attach this analytical mechanism to Rosrezerv, which would then be given a budget to act as a purchaser of strategic commodities that could then release supplies onto the market domestically when price spikes and supply crunches are forecast. Something tells me that’s not what they’re actually talking about, instead thinking of a data center that would plug into the platform Mishustin built to cope with COVID. It would then react as needed for political expediency.

The second half of the proposals concern policy support mechanisms that kick in whenever price levels cross arbitrarily decided “red lines” that will presumably correspond to inflation levels experienced by pensioners, those living at the poverty line, or else strategically and systemically important industries. Those mechanisms include, but aren’t limited to, direct subsidies, export duties and/or bans, ‘damping’ mechanisms like for refiners, subsidizing planting crops, and more. Rhetoric reaffirming the role of “market mechanisms” suggests they don’t actually want to introduce a more proactive planning system of the kind that western capitalist economies made active use of after WWII. It’s rather odd. If they were willing to create a strategic reserve or resource allocation system backed by state purchases, they could actually smooth price swings far more effectively. Think of the archetypal Keynes vs. Hayek debate over the economy — booms have a knack for eventually self-correcting in a manner that busts don’t. That is to say that higher levels of demand resulting in higher prices eventually lead to more production and rein in inflation, but lower levels of demand leading to slack, lower incomes, and lower productivity tend to teach firms not to invest into production unless demand is sustained.

A state reserve makes it easier to manage those balances and provide more confidence to businesses about the relative levels of supply and demand for given inputs so they can plan to increase (or not) output accordingly with a reduced risk of long-run inflation due to seesawing upwards and downwards demand as Russian consumers continue to tighten their belts. Ironically, it’s the lack of planning that’s the problem. By all appearances, the Analytical Center will be vested with the authority and capacity to quickly collate data and nudge ministries and agencies to action. Yet they’ll be doing so without an actual central planning mechanism, I’m guessing because the various organs of the state have become so captured and enmeshed in formal/informal power networks, lobbies, and interest groups that no one would accept that level of intervention. You’d need a strong central arbiter with the authority to make decisions that cost important political constituencies in the short-run. It’s easier to build a glasshouse in which no one can throw stones, and thus no individual is truly responsible for whatever policy outcomes ensue.

The formation of a defined inflation management policy comes amid a rash of global heatwaves that should challenge some of my priors about the politics of the energy transition as well as the (relative) paucity of interdisciplinary examinations of the political and geopolitical consequences of a rapidly warming planet laden with rentier capitalists and rentier states exporting hydrocarbons, metals, and minerals. In the US, the Pacific Northwest has smashed record highs straining and damaging public infrastructure not designed for the heat and raising the specter of air conditioning as a need, not an unnecessary luxury:

Earlier in June, temperatures in the Middle East shot up:

Siberia’s seen insanely high temperatures recently as well:

One of the operating theses of the unintended consequences of the energy transition is the concentration of ‘oil power’ in the Middle East over time because of its competitive advantages. I still think that’s structurally the case and don’t think Russia’s oil sector is well-positioned to increase output or ever capture marginal demand increases or else greater market share as demand falls. But as temperatures rise and strain the limits of what infrastructure and human beings can sustain, extraction in the Middle East, systems of hydrocarbon rents, and traditional inflationary concerns are going to face intense pressures. The Indus Valley in Pakistan and parts of the UAE saw temperatures climb above 50 degrees Celsius, effectively too hot for humans to handle and decades earlier than prior models had expected. The hotter things get in the Gulf and Iraq, the more pressure to invest into techniques that minimize human labor since efficiency declines in extreme weather, hot or cold. And this isn’t suddenly a net win for Russia. Weirdly enough, it’ll be the extractive industries in less extreme climates facing easier credit conditions able to substitute the most human labor the fastest while reducing net emissions footprints that would be most competitive. The fewer people are employed extracting resources over time, the fewer opportunities for poor Pakistanis and other migrant laborers who depend on the Gulf for jobs and remittances to send home to their families living in places becoming inhospitable faster than expected. I fully admit this is speculative but automation took place in the US oil sector after 2014-2015 so it’s not that speculative.

Heatwaves and extreme weather events are going to create inflationary shocks that no state can insulate itself from. If a heatwave or storm/hurricane take out a crucial bit of infrastructure at a regional trade chokepoint, that raises prices locally. If harvests fail due to droughts or similar events, food gets more expensive. If mining operations for cobalt in the DRC go on strike from extreme heat, your laptop’s supply chain will feel the heat as it were. Inflation as a concept and object of concern has historically been centered on monetary factors and levels of investment with some recognition that commodities, particularly food, face some constraints that exceed the power of the market to change. Some fixed assets are more fixed than others. Climate change is going to force us to reconsider the bounds in which we think of disruptions to supply/demand balances and how the oil & gas industry plays a large part in global flows of migrant labor and remittances.

Russia won’t ‘win’ from climate change because these events are going to accelerate the rate at which assets depreciate from wear and tear, raise insurance costs, and eventually costs of capital. ‘Greening’ economies requires significant to radical increases in investment, including in countries likelier than not to become ever more dependent on the US dollar and external financing because it’s cheaper than pursuing monetary sovereignty. I’ve never been a fan of the New Deal/WWII mobilization metaphors for climate action, nor do I think tribal groupthink around concepts like de-growth make any sense. But the level of investment needed now is extremely large and the space for political action in Europe, of all places, even narrower in fiscal terms than in the US where it’s narrow enough. Russia better start putting its money to good use now before things get too much worse, especially if it really wants to divorce itself from humanity’s last best hope of financing all the construction, reconstruction, and infrastructure to come: the US Dollar System.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).