Top of the Pops

The only bright spot for the oil market this year has been China, first hit by COVID, first to recover, and the only leading economy to aggressively target a supply side response without much social support.

China’s own National Energy Administration is calling increased investment into storage capacity to take advantage of lower oil prices for longer given that Europe is going to be juggling lockdowns through winter and the US is now in for the worst of it in terms of the virus. The bigger market and political trend, however, is that China is floating OPEC right now with its consumption, and the strategic dialogue between Beijing and OPEC is only going to strengthen coming out of this crisis. Storage capacity and buying up excess volumes to consume later may depress future prices, but they help keep Brent at or above $40 a barrel, a psychological hinge for market prospects as well as the bare minimum for many countries’ budget needs.

What’s going on?

MinTrans, MinPromTorg, MinPrirody, and a working group from “Autonet” are all joining hands in putting forward a federal law to stimulate the use of clean transport in urban centers. That includes electric transport and ICE vehicles using natural gas or hydrogen. It’s not some Great Leap Forward for green policy in Russia and it’s three months till we see the bill reach the Duma, per the reporting. It sounds like the go-to policy ideas will be tax preferences, schemes to exempt such vehicles from parking fees, vague offers of other tax exemptions, things like that. Really, what matters most are procurement promises and budgets. On that front, it’s going to take federal money transferred to the regions and/or cities to generate guaranteed demand. Doing so would give Russian firms a first mover advantage in trying to export or else invest in other Eurasian markets, places like Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan in particular.

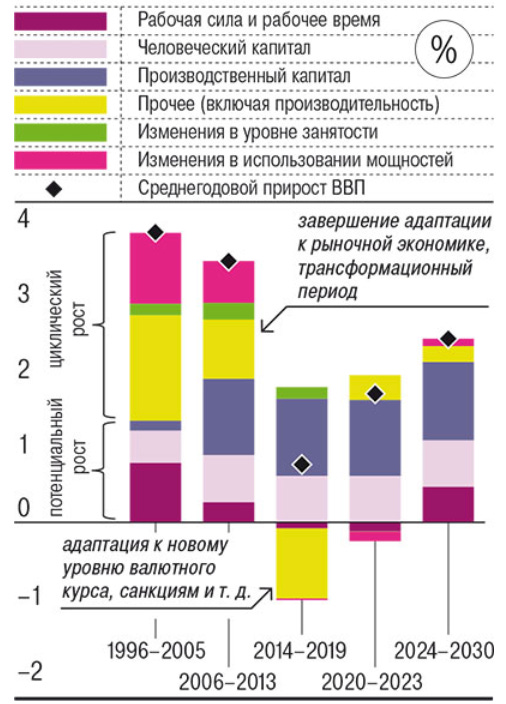

Ratings agency AKRA — in reference to the consensus forecast from Focus Economics — estimates that after the initial hit this year and virtually null growth next year, Russia will return to its “potential” growth in the 2-2.2% range annually by 2024. They’ve broken growth by source:

Dark Magenta = workforce and work hours Light Pink = human capital Blue = productive capital Yellow = other (including productivity) Green = changes in employment levels Light Magenta = changes in the structure of capacity

Note the chart distinguishes potential growth on the lower end of GDP from cyclical growth and flags that the 1996-2005 period was one of transition and adaptation and 2014-2019 involved a massive adjustment to currency devaluation, sanctions, and more. What’s fascinating in this breakdown is precisely that it eschews isolating resource rents as a share of productive capital and labor productivity. It also reveals the structural cause of Russia’s economic stagnation since 2013 — it exhausted all of the economy’s spare productive capacity inherited from over-production and misallocation of resources dating back to the Soviet period. AKRA’s forecast is a de facto endorsement of stagnation since it’s truly difficult to foresee a demographic breakthrough increasing the size of the workforce, or else the political will to force people to work longer. If we ‘nullify’ that contribution after 2024, it’s basically an annual growth rate of 2%, which is already the economy’s upper-bound and a status quo development. Not pretty.

Industrial consumers are now lobbying to change the rules for returns on investments to modernize old thermal power plants, calling for older plants to effectively be compensated with 35% of the earnings from more competitive sources of electricity to prevent shorter-term price increases and reduce the overall level of mandated subsidy support from the energy market. Power companies rightly point out that this would end up harming the competitiveness of newer plants and actually end up with more closures of older thermal plants by eroding investment into new capacity. Time horizons are the issue. Since Russia uses price controls and subsidy agreements to prevent cost inflation and allow industries to remain competitive despite lagging when it comes to productivity improvements, it disrupts the investment cycle, ironically, because the plants to be modernized receive guaranteed payments, and hence face incentives to prolong the process. It’d be better to make businesses eat temporary cost inflation now before costs decline in relative terms vs. inflation as more capacity comes online when the external markets are more normalized. The investment into new capacity would generate more employment, more domestic demand, and more business than modernizing existing infrastructure. But industrial firms have to claw for earnings against other sectors since these systems of price support and controls mirror problems of sectoral balances dating back to the Soviet system pre-Gorbachev.

At first reading, the Duma has passed a bill delegating power to regional governments to confirm plans for the construction and reconstruction of apartment buildings, not just buildings in extreme disrepair, so long as avenues for input from local citizens are part of the planning process. The aim of the bill is to accelerate the replacement of buildings falling apart per national targets as the number of buildings expected to become dangerous for their inhabitants is set to rise significantly in the next decade as Soviet-era structures age. Further, Soviet-era planning systems built around urban micro-regions frequently undermine commercial development and the best use of the land available. The bill is a net good, even if the process is going to be captured by local political interests, but it’s an interesting case of trying to formally empower local authorities to better address problems without providing more fiscal autonomy, equivalent to an exercise in flak-catching a la Tom Wolfe. The bill will be amended over the next 30 days before being voted on for its likely final form.

COVID Status Report

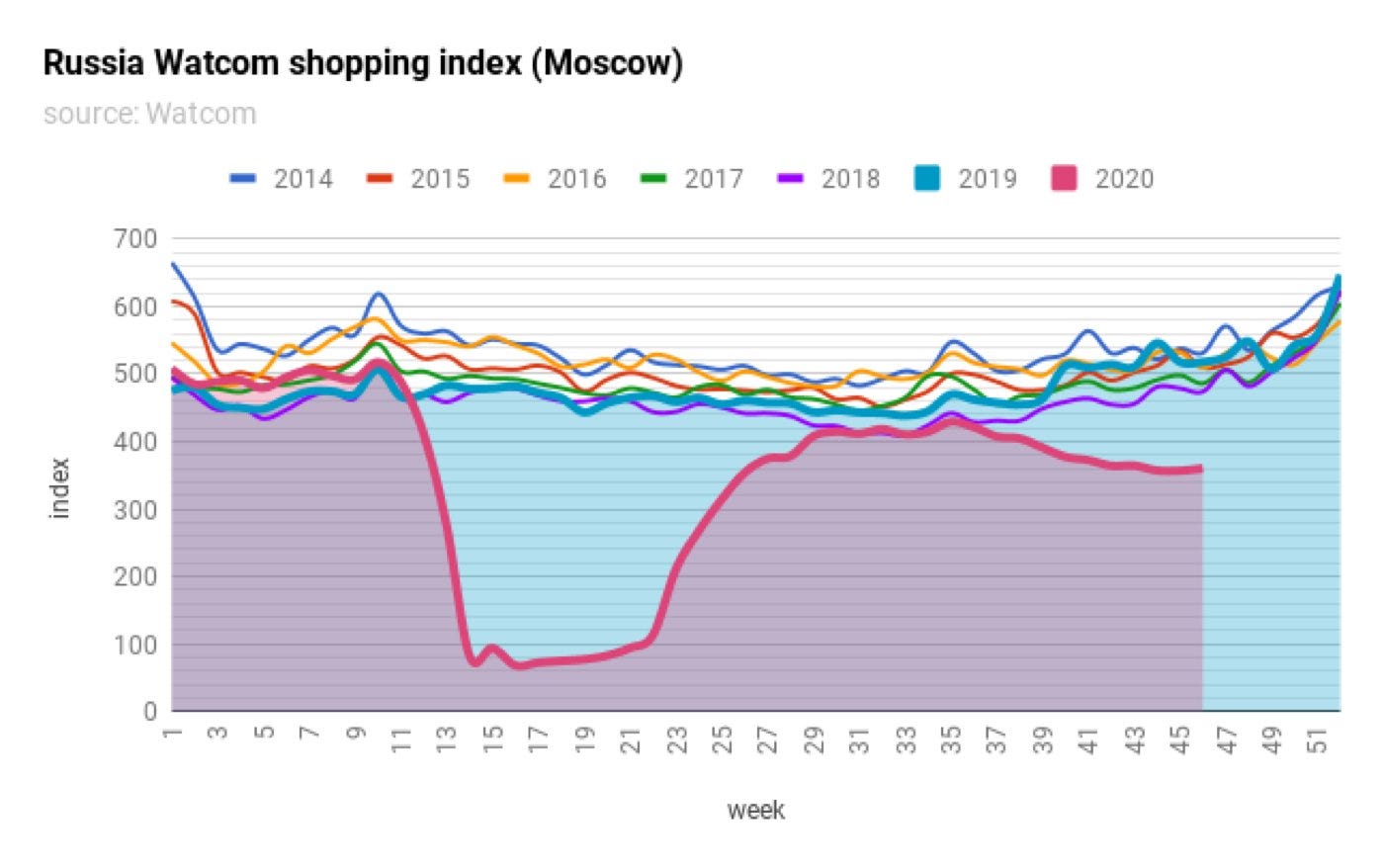

Daily infections are up past 23,600 for the last 24 hours. There is evidence that infection rates across the country began to decline in early November, which suggests that even with improvements to the testing regime, something’s missing. Russia’s passed the grim milestone of over 2 million total infections. Regional health authorities aren’t coming out for a mandatory testing regime for domestic travel, but it’s an option on the table. Foot-traffic at malls is still declining, but appears to be stabilizing in Moscow. I’d expect the numbers in a fair number of regions to look worse for November:

Worst.trade.ever.

Trump became the face of trade wars from his campaign in 2016 — never mind that Bernie Sanders wasn’t far off from endorsing the same types of tactics — but he exemplified a broader trend that had been developing in global trade since the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Restrictions steadily rose as the recovery that followed was grossly uneven, not just in the United States, but globally. From the latest WTO trade monitoring report. Trump supercharged tariffs within the G-20, but they had structurally been rising before he came into office:

Despite the complete failure to coordinate stimulus policies between the US, the EU (well, even within the EU), China, and Japan, there had been one bright spot since the crisis hit: more measures facilitating trade than restricting it had been adopted by WTO members, at least back in May. But the October data shows potential red flags. There have been 84 facilitating measures vs. 48 restrictive measures put in place, but the volume of trade affected by each is a bit more even between restriction and facilitation:

Facilitating measures are being pulled back now and while the volume of trade affected is relatively small, the political fights over recovery are just beginning. If you look at the WTO breakdown of % shares of cases in which a trade safeguard under WTO rules was initiated by type of product, there’s potential overlap to affect energy transition policies:

The question of course is which metals have been involved and, admittedly, it matters just as much who’s actually initiating a safeguard too. But marginal changes in price inputs for metals make a world of difference for mining firm profits as well as end costs for consumers. Take the example of electric vehicles. Costs for batteries will continue to fall as newer technology, production techniques, and designs are implemented, but metals make up the marginal input costs for the single most important part of an electric vehicle. Ignore the spot prices as they’re static references that have dated out, but you get the idea:

An incoming Biden administration can’t just put the genie back in the bottle after Trump’s team challenged the WTO. Now that the US and EU are targeting Huawei for trade on security grounds, the WTO’s reticence to rule on security exceptions for trade is going to be tested to the limit. The reason was always simple. A multilateral organization regulating trade would lose a huge deal of political capital if it denied countries the right too liberally to invoke national security as a justification for trade restrictions. It’s why you’d only see the arguments heard over egregious cases. It’s easy to imagine that states will eventually be empowered to apply the same logic to metals and minerals as strategic animosity between China, the US, and EU deepens.

These trade fights are a considerable downside risk for future growth:

You can clearly see how European austerity increased trade’s relative share of GDP as external demand propped up Germany and the Euro area. Russia’s reliably around 50%, with any decline largely a result of a fall in commodity prices and not substantive shifts in the structure of its economy. The Biden administration faces a particularly interesting pressure point, though. In order to please the Democratic Party base, he’ll have to make progress supporting US manufacturers, particularly in the Rust Belt, and couple that with a reassurance campaign for US trade partners and allies. But the Trump administration has blown the lid off of anyone’s faith in being able to trust US trade policy past the 4 year window of any given president so no matter how orthodox the incoming administration intends to be, there’s a new reality for policy planners elsewhere on top of rising pressure to renegotiate the terms of the economic settlement that underpinned the US commitment to free trade. After all, lowering trade barriers was a crucial corollary to becoming the world’s consumer of last resort. Americans have to consume more than they produce to keep dollars flowing abroad, which means they have to be in debt, struggle to export, and see the costs of non-tradable services like healthcare and education bid up and up. The costs of that reality have become stark.

Trade fights aren’t going to end up being a large drag on demand for metals and minerals, at least I don’t think. The factors driving future demand growth with the energy transition are foremost about fiscal policies and things like banning the sale of ICE vehicles, factors that are much stickier than marginal costs passed onto the consumer. But they are a net negative for broad economic growth, and therefore oil prices. It’s important to remember that the energy transition, while creating a host of new economic activity, is going to be destroying plenty as well. The promises of massive job increases and surges in wealth are a pipe dream. A lot of people already employed to do their jobs are going to do a bulk of the work realizing things like construction or electrical wiring. Oil exporters are in a bind on that front, but Russia’s not going to liberalize trade anytime soon, at least not on terms that would threaten the political stability of employment and support for the regime.

Clinton’s Shadow

If I were a Russian policymaker, I’d be worried about a Biden administration’s foreign policy, and not because of sanctions and the like. It’s Syria I’d worry about:

McChrystal, literally fired for insulting Biden and Obama, hounded the White House to surge more in Afghanistan without any hope of recreating the magic that was the strategic hamlet approach in Vietnam. Blinken is a guy who, aside from the personal investment in how Syria went wrong, supported Trump’s decision to attack Assad for using chemical weapons. I make no claims that it wasn’t true he had, but if that’s the bar for going after the regime, the military is going to find an easy way to clear, especially since Blinken has signaled Biden will keep troops in Syria. Recall that Paris was touting Bellingcat as evidence we had to act, a move that suggests either they didn’t want to reveal what they know from real intelligence on the ground or, more likely, they knew that doing so would engender public support by making it appear to be objective and independently sourced. Going back to 2012, France had backed the creation of a no-fly zone in Syria.

Samantha Power is the ultimate “Obamacon” who disagreed with his approach to Syria and, one imagines, is going to advocate endorsing the Bartlett Doctrine from The West Wing, committing the US to use military force on purely humanitarian grounds as a matter of principle. Hicks is a deep-in-the-weeds wonk who knows defense backwards and forwards but is probably reflective of the status quo maintenance Biden projected on the trail. Burns was lobbying the Obama administration to create a safe zone in Syria as late as 2016. Avril Haines was a deputy of Susan Rice’s, and we all know that Rice earned her stripes building on Albright’s legacy of intervention (right or wrong). Parse her and Power’s logic on attacking Assad over chemical weapons in 2013 and it’s clear that they’re careful to leave room for future policy pivots the other way.

Middleton is CIA, so there’s almost nothing out there to judge. Austin handled the Syria portfolio under Obama for CENTCOM. McRaven supports attacking Assad to deter chemical weapons attacks before swiftly pivoting into a belief that we should be prepared to do more and let Moscow know that Assad has to go and we’ll act accordingly. Stewart ran defense for CENTCOM when the DoD inspector general and relevant oversight committees including Armed Services launched investigations into whether or not CENTCOM was manipulating intelligence in Iraq and Syria. Thomas-Greenfield is part of Burns’ cadre from State and they have a joint (and I hope robust and actionable) idea of how to save the department after Tillerson and Pompeo’s tenures. Work is part of the think tank world, drawn from CNAS, and in there more for things like defense spending priorities and maintaining the United States’ military edge against adversaries. Cohen is also from CNAS this go round and has a background fighting ISIS from a post at Treasury.

First, to clarify. Anytime anyone says “no-fly zone,” they’re referring to a ground invasion, even if a small one. The reality is that planes need targets that are verified. Satellites and drones can only tell you so much. There’s got to be someone on the ground either painting a target or else confirming that it’s good for a strike and once you’ve got a permanent presence doing that, it means they need logistical support. That logistical support then has to be protected from attack. Next thing you know, you’re being told the US has to increase deployments to protect its soldiers rather than pull them out of harm’s way. Second, in no way am I suggesting that these collective voices are going to get into Biden’s ear like Wormtongue and call for a massive escalation. However, when you surround yourself with a collection of experts who are going to assess intelligence and threats based on their priors as well as advocate for policy responses they may see as proportionate, but entail large risks, you’re likelier to come round over time. Syria may have become an ancillary concern this campaign season, and for most political observers, but it remains the mother of all tripwires for a broader conflict in the Middle East. A wrong move attacking an Iranian position, Assad, proxies affiliated with Turkey, Russian mercenaries, it all can go pear-shaped.

The reason I’d be worried if I was Moscow is because, after facing the humbling truth that it’s getting harder and harder for Russia to dictate outcomes in Belarus, Armenia and Azerbaijan, to plan around events in Kyrgyzstan, etc., escalation risks in Syria have hinged on Trump’s moods the last 4 years. Trump, crazy enough to countenance assassinating Assad at one point, was ultimately cowed by the large part of his base who were anti-war. Biden faces no such impediment. Biden’s team, including Flournoy who’s expressly stated that the US has to have a role negotiating in Syria in a major way, all appear open to using the incremental backdoor provided by no-fly zones and deterrent strikes. If anything escalates in Syria, Russia’s position in the Middle East is suddenly in question. It’s always relied on being the partner of second resort or poking around the edges to maintain its needs. It cannot afford to stop the US if there’s a sudden change on the ground. Escalation happens in increments and isn’t predictable. If you kill a militia fighter’s friend in an airstrike and he knows the US did it, don’t be shocked if he opens up on US troops who can’t engage without verification that it’s a target they can shoot at. It just takes a few mistakes to kick things off.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).