Top of the Pops

First off, a response to the Munich Security Conference and latest developments for US policy and negotiations over the Iran deal will drop later today (would have Friday but wanted more time to let things unfold after Biden’s speech). Now, to business.

It’s hard to ignore the latest development in long 2020 — Rospotrebnadzor and MinZdrav confirmed that seven workers at a poultry factory in Astrakhan oblast’ were infected with bird flu, the first recorded case of strain H5N8 jumping from birds to humans. All seven reportedly never got too ill and recovered just fine. All relevant data was sent to the WHO, which is now reviewing it. The latest in our luck as a species comes just two weeks after Russia’s health authorities are discussing the link between anti-COVID measures, potential ‘conflict’ between viruses, and a fall in recorded cases of the flu. Egg prices in Russia have been rising because of the impact of bird flu on production, a problem that’s been experienced across much of the world the last few months without too much comment on the nightly news. What’s more worrisome is that the strain that hopped species in Russia is the same that hit Cornwall earlier in the UK. Not exactly what I’d like to hear as we now stare down the barrel of a steady re-opening in phases per current plans and vaccination rates in the UK.

Given it’s happening everywhere, by itself, the appearance of bird flu in southern Russia isn’t a crisis to panic about. But the story draws yet more scrutiny onto Russia’s agricultural sector when it’s seeking to secure exports to the Chinese market. China’s ban on Russian pollock imports, effective Jan. 1 citing COVID safety concerns, has created a massive pollock glut on the Russian market and denied the fishing sector potentially hundreds of millions of dollars in export earnings. The ban has effectively been extended to all Russian seafood exports the current roadmap to address sectoral shortcomings has done little to assuage concerns in Beijing. If Russian poultry becomes suspect, it’ll harm efforts to negotiate for greater market access, which are needed to help maintain Russia’s trade surplus with China in the longer-run, particularly as the CNY appreciates making machine parts and equipment imports more expensive against what will likely be an oil price facing a declining inflation-adjusted price ceiling. Any new cases leading to human-to-human transmissions should set off alarm bells given how lax the enforcement and adherence to health measures have been in Russia overall, especially with public fatigue setting in thanks to the limited income support that’s been offered. Russia isn’t China. While I have confidence authorities can contain an outbreak, nothing like Wuhan is conceivable as far as I can tell after the regime’s spent most of a year explicitly or implicitly talking up natural herd immunity and won’t acknowledge the connection between excess deaths and inadequate public measures to fight COVID.

What’s going on?

Next week, United Russia is holding a 2-day seminar with the leadership of all its regional staffs in what seems to be in hopes of uniting the party’s strategic aims for this year’s campaign season and the party primaries in May. Everyone knows it’s a necessity as the electoral chaos unleashed by Navalny’s protests and now the splits within the KPRF between the old guard leadership and younger party members are pushing at the limits of the Kremlin’s attempt to crush any non-systemic opposition challenges. The seminar follows meetings held by the domestic policy bloc from the presidential administration meeting with all of the regional vice governors and pressuring them to figure something out. The minimum figure for Election Day performance as a party list seems to be 45%, but that’s widely seen as inadequate to guarantee the constitutional majority the regime prefers and the ability to unilaterally pass bills with fewer concessions and haggling over policy lanes or creating yet more systemic opposition parties to stand in for certain social issues and drain votes away from any real opposition challenges. A low turnout producing a much higher result for United Russia may end up proving more desirable than a higher turnout scenario where its shot at the majority is thwarted. The elasticity of the public’s willingness to accept that these elections aren’t meaningfully about political competition and the state of economic affairs heading into September can scramble these assumptions fast, though.

Research from the Center of Development at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow shows that retail volumes still have some ways to go fully recovering to pre-pandemic levels. Overall, however, 2020 just accelerated pre-crisis trends for the retail sector rather than marking a change in direction:

Title: Physical volume of retail turnover (% vs. same period in 2019)

Green = all goods Yellow = foodstuffs Blue = the rest

What’s most telling here is that the gap for consumer goods from 2019 kept narrowing at the end of 2020, yet people were buying less food as prices rose significantly. Another weird aspect of retail in Russia is that it actually accounts for a higher % of GDP than in the US (4.8% vs. 3.7%), but that’s a reflection of the lack of value-added output elsewhere given that even though Russia remains the world’s 8th-largest retail market, Russian consumers have lost nearly a decade now to stagnant or falling incomes. And retail has produced the most new jobs the last 3-4 years, which are lower wage without corresponding improvements in high wage, higher-productivity jobs. Therefore, it’s the food data that should really be worrying and where we should expect to see yet further retailer consolidation.

The Ministry of Finance is now working out a new law that would create a separate division within the existing state accounting system to include all companies under sanctions that would be not be available to the public. Existing protections for balance sheets apply to all budget-financed organizations (other than state companies), the central bank, religious organizations, and companies/organizations working with state secrets. This comes on top of the significant portion of budget expenditures that are legally classified in Russia — this year, it’s expected that 3.2 trillion rubles ($42.88 billion) or 15% of the budget will be classified, slightly lower than in past years with higher relative defense budget spends. The irony of these measures is that every move MinFin takes to try to weaken the oversight and enforcement powers of the US Treasury, the less attractive they make their own companies (even if sanctioned) for foreign partnerships. Even China’s SOEs and parastatals want to know that their partners on heavily politicized deals are above board. It’s exceedingly difficult to imagine a firm like Rosneft, for instance, inspiring confidence, but the damage affects other firms as well. The pursuit of sovereignty from foreign financial influences ends up undermining the space for unsanctioned firms to attract foreign partners because it creates a second level of political risk for any counterparty: they have to worry about a shift in attitudes in Washington and Russian policy suddenly throwing up a new roadblock for due diligence over a joint project etc. Given how concentrated FDI is at the sector level, this won’t help anyone but those dependent on the budget for their business. Insulating the Russian economy from sanctions continues to worsen the institutional environment for Russian businesses, even if unintentionally.

The latest labor market data from sociological surveys shows that women are suffering more than men when it comes to employment — and suggest that self-reported changes in wages may not quite be capturing what’s happening:

Title: Change in pay since the start of pandemic, % of employed

Red = paid more Blue = paid less Yellow = about the same Grey = hard to say

Descending: 2nd wave, 3rd wave, 4th wave

Wages may well be rising for more people because of market-specific shortages in labor associated with the decline in migrant flows. But gender roles for women have made each successive wave more difficult. It’s most likely that productivity data would show that women who are remote-working have been less productive than men, with the vast majority of the gap explained by expectations to take care of kids at home, cooking, cleaning, and other often gender coded activities at home, or else their own employers’ treatment of their split responsibilities. Whereas women with children are effectively punished by lower wages and fewer opportunities for advancement or to be hired in the first place, men often receive a 2-3% wage increase with their first-born (and the wage gap between men with children and men without is 25% on average). Unemployment among women was nearly 50% higher as of September than in March and still on an upward trajectory vs. less than 30% and falling for men. Wage increases, therefore, may partially also reflect businesses’ reticence and sexism when it comes to hiring women for positions they prefer to give to men generally. More research is clearly needed. It’s a good reminder of how topline data almost never tells you the story when you start picking it apart and why Mishustin’s initial talk of a ‘new social contract’ in January seemed to primarily target increasing social transfers for women with kids.

COVID Status Report

New cases came in at 12,604 — 3 straight days under 13,000 now — and reported deaths fell to 337. Moscow appears largely flat with the decline happening in the regions. The regional map showing % of the population who’ve received one dose of Sputnik-V (darker = higher %) isn’t great given that the vaccination campaign was ostensibly launched first in December before going national in January:

At those penetration rates, vaccines might help a bit. But if the UK experience is any guide, they had to get nearly a quarter of the population to have one jab with the initial wave getting their second dose before the data truly reflected the impact of the vaccine. The distinction of course being that the UK has strict restrictions in place and they aren’t in Russia, which could change causal inferences drawn somewhat. Assuming this data is correct and the regional figures are simply underreported or badly kept due to capacity constraints, then things are going quite well, all things considered. Countries like Chile have leapt ahead on vaccinations largely because they decided that any cost was worth it to acquire vaccines. That’s not been the government’s approach in Russia, and while this data is encouraging, it’s going to drag out the recovery.

Coming in Hot

As usual, OPEC+ is internally at loggerheads over what the strategy should be from here on out. Russia wants to boost output now while Saudi Arabia is happier to take the cautious approach and wait to see how the shale patch in Texas recovers. There are sure to be fireworks at the upcoming meeting on March 4 (well, at least for those in the weeds on oil markets). What it comes down to is how strong demand looks by summer and how resilient US output proves to be. Baker Hughes’ oil rig count last week only declined by 1 — drillers aren’t setting rigs aside since they plan to drill once they get back to it, and it seems like we have every reason to assume that the rig count will keep rising, just at a slower pace than past years. Greater discipline and lingering fears that rising US Treasury yields will trickle into the corporate bond market that’s underwritten the equity bubble that is US shale since the global financial crisis are cause for caution. There are related fears higher yields will hurt stocks, which would also affect the ability to raise capital secured used stocks. That’s going to weigh on the oil market later in the year if those fears are realized:

While Riyadh is cautiously watching US debt markets, Aleksandr Novak isn’t just pushing to ease cuts, but also lobbying for new support measures for the oil sector domestically, including further tax revisions after the repeal of tax breaks last year cost the sector billions in foregone profits. MinFin is proposing a set of new changes that suggest they aren’t too worried about the sector but want to throw it a bone: they want to index indicative wholesale prices for fuels at 1% annually instead of 5% by 2024, peg the indexation of excise taxes to the CBR’s target inflation rate (4% annually), new effectiveness requirements for tax breaks so that they can force firms to meet their obligations, and reduce the mineral extraction tax burden for hard-to-reach reserves a bit. The biggest change there is the wholesale indexation for retailers since 5% annual markups happening while the actual end price of fuel may be relatively unchanged due to broader demand and crude oil price dynamics would squeeze the margins of Russian refiners, rendering the mechanism pretty useless at compensating them for losses incurred depending on the external market environment. Novak probably wants more relief than MinFin’s offering but these two things happening in tandem suggest that the presidential administration has instructed the cabinet to avoid direct spending to help the oil sector at all costs this year. The only way to increase investment activity across the broader economy because of how low services’ share of GDP is and the lop-sided nature of recovery and pandemic aid will be an easing of oil production cuts that then increase intermediate demand in other sectors. It’s basically a tacit admission that Russia has not broken its economic oil dependence in the new budget cycle.

What increasingly matter for global oil demand, then, are the geopolitics of growth that have emerged during the initial recovery phase from COVID. As Iika Korhonen from BOFIT notes, the appreciation in the yuan has been driven by China’s faster overall economic recovery and supply-side stimulus while other economies continued to experience deflation in their consumer goods manufacture or export sectors. NEER is the nominal effective exchange rate and REER is the real effective exchange rate:

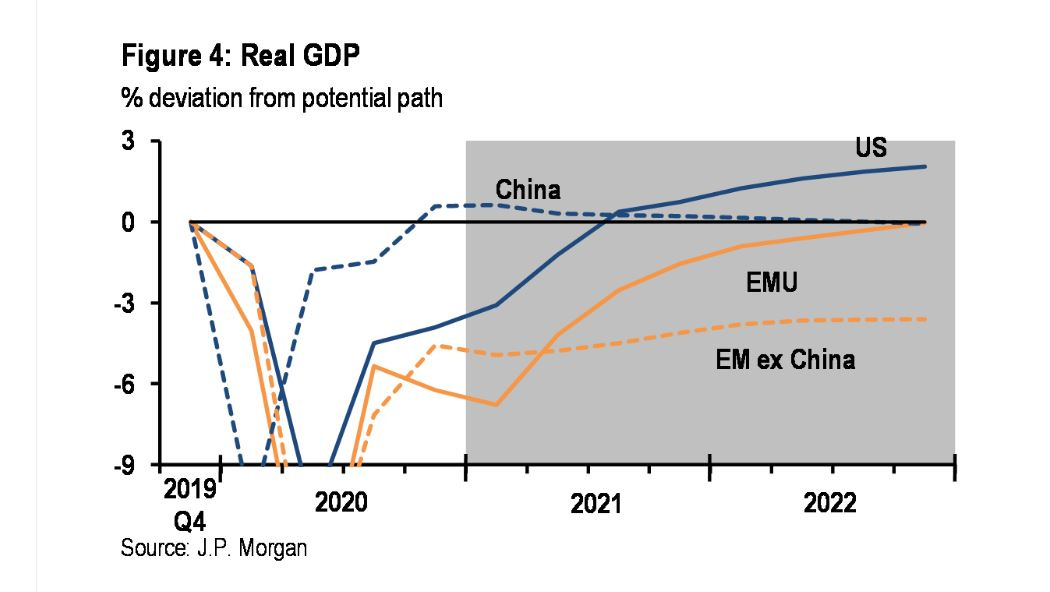

As we know, currency appreciation erodes export competitiveness over time. The initial (re)inflation in the Chinese economy was deflationary for competitors — their factories weren’t producing and the relative weakness of China’s consumer recovery meant there was a glut of consumer goods that had to go somewhere. That dynamic shifts as other economies open, the sequence they open in, their own stimulus policies, and more. That’s why it struck me that JP Morgan now projects US GDP to exceed its prior potential growth on a sustained basis through 2022 (and potentially into 2023) while China reverts to the mean this year, Europe only claws its way back to its (stagnant) norm by the end of the 2022, and broader emerging markets excluding China remain depressed through 2022:

The usually bullish Goldman Sachs has now lifted its Brent crude price forecast in the months ahead into the $70s per barrel. That would be enough to trigger a much bigger revival of interest in US shale output, realistically. But that has a more pronounced impact on the demand side depending on the rate of recovery by geography. Emerging markets and oil importers always benefit — at least for their oil demand — from a weaker US dollar. Fewer dollars are being spent from currency reserves to cover imports and so long as the domestic currency is stable and trending upwards agains the dollar, the cost of fuel is cheaper. But a weaker US dollar doesn’t help you consume that much more if the lack of vaccinations reduces the ‘risk on’ appetite of foreign investors chasing better returns. Similarly, if US bond yields trend higher for longer — I personally doubt that they will stick, but it’s an important factor — the relative draw of emerging markets outside of China for yield diminishes. The US ripping ahead on growth might end up drawing more investment as well. FDI figures the next 18 months in the US vs. China will tell a fascinating story of investor perceptions and growth opportunities. If emerging markets outside of China see considerable delays in vaccine procurement and recovery, that’s disastrous for the oil bulls’ prospects outside of the initial recovery window — non-China non-OECD economies accounted for about 38% of global demand pre-COVID. An ever growing share of global trade is conducted between economies considered to be in the Global South. If you exclude East Asia from trade data, south-south trade has fallen at levels exceeding what we’ve seen in developed economies. Oil demand in most may be ‘sticky’, but it’s got a long ways ahead to grow much.

At the same time, Europe’s showing the same inability to spend from the last global crisis while its own bond markets that would finance said deficit spending are reacting to the current rise in yields on US Treasuries:

It’s getting slightly more expensive to borrow as US Treasuries rise without the same type of inflation expectations derived from a robust recovery you see in the US narrative. And that’s before making any claims about the effectiveness of energy transition policies or that Europe’s EV market took off last year, even if from a relatively low base. The biggest counterargument to a weak demand environment heading into 2022 is that US stimulus will feature a great deal of redistributive components of fiscal policy putting more spending power in the hands of the poorest. The poorer you are, the more commodity intensive your consumption is since you’re probably not consuming expensive services. You’re paying for food, housing and utilities, clothes, stuff made with plastic and petrochemicals and not much else. That could theoretically jolt US demand higher initially, but it would fall off as a result of Biden administration policies and markets pushing to improve fuel efficiency, battery tech, and more.

All told, Novak’s push to produce more now is a form of trade-off in economic stimulus. Accept that lower prices are likelier to follow, which may hurt the budget some, but earn back some of those taxes from greater economic activity — think consumption taxes like VAT — and higher profit tax earnings elsewhere in the economy. The added benefit is that employment figures most likely track upwards as well. The as yet unexplored side of the distribution of recovery remains what happens if the US growth rate actually does remain higher for longer. For one, it’ll take China longer to close the gap with US GDP — to be perfectly honest, I think fears it will do so are overblown. For another, it would slightly increase the cumulative effect of US climate policy on changes in marginal demand for oil compared to China and possibly affect how non-China emerging markets consume commodities a bit as well. For instance, mid-sized firms in the US have been in relative decline for 50 years now. The nature of the COVID shock was a boon for companies that could scale. Companies that scale like an Amazon are effectively planned economies of their own responding to external market events and trends. Greenwashing many of them may be, these corporations are seeing their relative normative power over markets growing and many are bound to want to push ahead with carbon emissions reduction targets and fuel substitution. A faster growing US market makes that all the more attractive. The race is on now to ‘win the peace.’

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).