Top of the Pops

As demands that Nikol Pashinyan resign spread in Armenia, the government is warning the public and opposition against any potential “coup” attempt. President Sarkisian is now talking to political parties to try and build some unity, but already having thrown Pashinyan under the bus for surrender, he’s probably looking out for himself first and foremost. The real coup to come, however, will be a result of financial power. As Azerbaijan establishes itself in the newly acquired territories, people living in Karabakh outside the Stepanakert bubble are going to use the manat. They’re going to start using Azeri banks, they’re going to suddenly benefit from a financial system with a steady influx of dollars and Euros and a massive wealth fund that manages exchange rates and banking sector liquidity. Those still living in Stepanakert are going to face even tougher financial conditions getting loans, access to credit cards, trading if they don’t start using manat more. Those little things around the edges add up over time, influence illicit flows as well as business planning, and finally can reshape economic relations between residents of the Armenian bubble left behind and the rest of Armenia unless the corridor, as proposed, is somehow enough. But the tenuous reality of relying entirely on a land bridge policed by Russian peacekeepers sent by an allied government that doesn’t legally recognize Armenia’s claim to the land and only stepped in at the last moment is not going to sit well.

What’s going on?

Russians started taking out more credit card debt in August-September after a half year of sitting tight on spending, per data from Tinkoff and the Bank of Russia. But the net increase in credit card debt this year — about 2.5% or 42.2 billion rubles ($554 million) — is minuscule in demand terms, and September figures showed a dramatic slowdown from August. More interesting is that the rate of credit overdue more than 90 days at the end of September fell slightly to 6.8% from end of last year. For one, people may have prioritized paying down debts while in lockdowns. But I’d wager that the only reason any improvement showed up is because of the growth of debt that is unsecured and taken out in the informal economy or from microlenders.

Analysts from RusEnergoProyekt and the Skolkovo Fund put out estimates for potential annual savings for different oil firms if they invested into improving energy efficiency for refining:

Blue = potential reduction in energy use (billion rubles/year) Purple = volume of investment for refining in 2020 (billions of rubles)

Smaller players tend to be much better at managing their energy efficiency since they have to focus on savings rather than acquisition-led growth. The big outlier is obviously Rosneft, which has never been a company particularly good at managing its own assets to pursue organic growth and cost-savings, but rather has relied on a heavy debt burden and acquisition-first strategy. With production growth constrained by OPEC+ and European refiners now beginning to look at closures, Russian refiners need to improve operating margins. This is especially stark when looking at just how much products demand recovery in Europe is lagging Asia, a set of markets Russian firms cannot penetrate because of China’s refining capacity alone.

Good news! Natura Siberica is now looking to market its brands in the US and. Europe and currently in talks with IHerb while Librederm hasn’t gotten back to them. It’s expected that sales in Europe could start in within the next year. The size of the cosmetics markets in Europe and the US dwarf Russia, and external growth is undoubtedly going to be a better means of diving up corporate earnings than internal growth. Even with how bad things are in Europe, market size and access to the EU can be a boon. There’s rarely that much in the way of good news and this isn’t a gamechanger or a particularly large company. But it goes to show that firms operating on domestic markets that aren’t worth the political trouble of state control or domination can be competitive abroad, even in the current political climate.

Anna Popova of Rospotrebnadzor has a bright idea to save Krasnoyark residents from pollution — gasification. The proposal entails moving the residential sector and smaller businesses from coal power to gas. At present, the central and southern parts of the city aren’t hooked up to the grid. The Federation Council is set to discuss it at the next hearing on gasification across the country. Deputy Minister Alexander Novak estimates gasification in Krasnoyarsk would cost 125 billion rubles ($1.6 billion). The entire situation is shambolic. Gasification has been a buzzword priority since 2006-2007 and that price tag would likely be inflated by uncompetitive tenders, shell companies bidding for contracts, and so on. Though a big improvement over coal, Russian officials seem keen on proving again and again that they’re out of ideas because of the system they inhabit.

COVID Status Report

Daily infections came down a bit to just under 20,000, however it’s not particularly good news. The decline was entirely in Moscow where capacity to implement and enforce measures is greatest:

The longer the cases keep rising, the less of an impact success in Moscow has on the topline figures and the less relevant mayor Sobyanin’s handling of the pandemic is to getting it under control even as Moscow remains the country’s over-centralized economic hub for a wide array of business activities. Sergei Ryabkov from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is assuring the press that Russia’s in serious talks with Brazil and India to coordinate vaccine efforts. Clearly it’s policy Bedlam and no one knows what comes next.

Future’s So Bright, You Gotta Sell It

Oil prices continue to rip upwards on Pfizer’s vaccine announcement, which on one hand, seems logical, and on the other looks incredibly stupid. Anyone in the market with exposure to energy and oil in particular has been praying for good news since March. Year-to-date returns for large oil firms have been immiserating, even with the last few days’ uptick factored in. Note that this excludes reinvestment of dividends, which would alter it but not significantly in most cases given cuts, suspensions, etc.:

Brent’s trading north of $45 a barrel again based entirely on the assumption that not only do we have a winner of a vaccine in the pipeline, but it’ll be distributed adequately and, somehow, the economic devastation of this year won’t have long-run effects. All three of these are leaps. Pfizer put out that statement without even having finished the trial and no one has access to their data to independently verify their findings and claims. We’re going to have vaccines, of that there is no doubt. But even if it ends up delivering as promised (which it well might do!), the logistics are daunting. Pfizer’s vaccine has to be packed with dry ice and comes in two doses administered 28 days apart. Most states in the US have no idea yet how they’re going to handle distributing a vaccine that has to be held in ultra-cold storage, especially in rural areas. And that’s before getting to where oil supply and demand dynamics are going to be.

For starters, servicing costs in the Permian are now down thanks to the knock-on effects of a weak labor market and weaker demand forcing service providers to slash prices and cut costs (and corners…). That means that drilled but uncompleted wells are now getting another look from shale players. It’s not cause to celebrate about a resurgence in output with longer-term activity, but it’s there lying in wait. Vitol’s now looking at possible shale acquisitions on the cheap next year while capital flees and tries to find value elsewhere. The temptation is to write off future output because shale is left to fight over diminishing marginal demand increases or else decreases while not sitting on the most competitive part of the cost curve. That’s silly given that the horizon for returns on investment for a given project is measured in weeks per well, not decades. Even short-term price rallies driven by emotional exuberance like the current one can convince a few risk takers to boot up supply again so long as it can be carried away and sold. Capital is always going to snake its way back to take a chance.

There’s also the issue of brownfield management from a lot of the world’s oil giants. Saudi Arabia, even if it is lying about its reserves, reliably has some of the best in the business helping it manage output decline because it can easily poach talent and import services from the US or Europe thanks to long-standing business ties going back to the 70s when they started trying to replace foreign workers with Saudi-trained talent. Russia, however, is in a more interesting bind.

Putin has been urging the oil sector to shift its priorities to greenfield development i.e. invest into new oilfields while maintaining tax increases that MinFin is depending on to help cover budget deficits. Vostok Oil could cost as much as 10 trillion rubles ($131.1 billion) over its lifetime and might not realize large crude volumes until after 2030, the prospective earliest date for peak oil demand per comments from MinEnergo’s Pavel Sorokin. Oxford Energy’s analysis from late 2019 offers a useful reference point for the balance between green and brownfield oil production:

Rosneft has begged for tax breaks to maintain output at its core brownfields, and other firms need help too. Shifting focus onto greenfield development is likelier to accelerate production decline since, as it is, Russian oil firms see limited upside to higher prices because of the progressivity of the tax code and how it’s linked to the price of Urals blend and the ruble/USD exchange rate. If prices rise significantly again, the ruble will strengthen, thus increasing relative costs for Russian producers while their effective tax burden will also rise. It’s purgatory for businesses planning new investments. While those investments into production go ahead — Lukoil has been particularly good at managing its output diligently — the relative costs of brownfields will rise too. It’s only when oil prices collapse towards $30 a barrel or lower that Russian firms really start to sweat it. Trouble is that might end up happening again next year if the worst fears about a Biden administration easing sanctions pressure on Iranian and Venezuelan volumes of crude comes to pass.

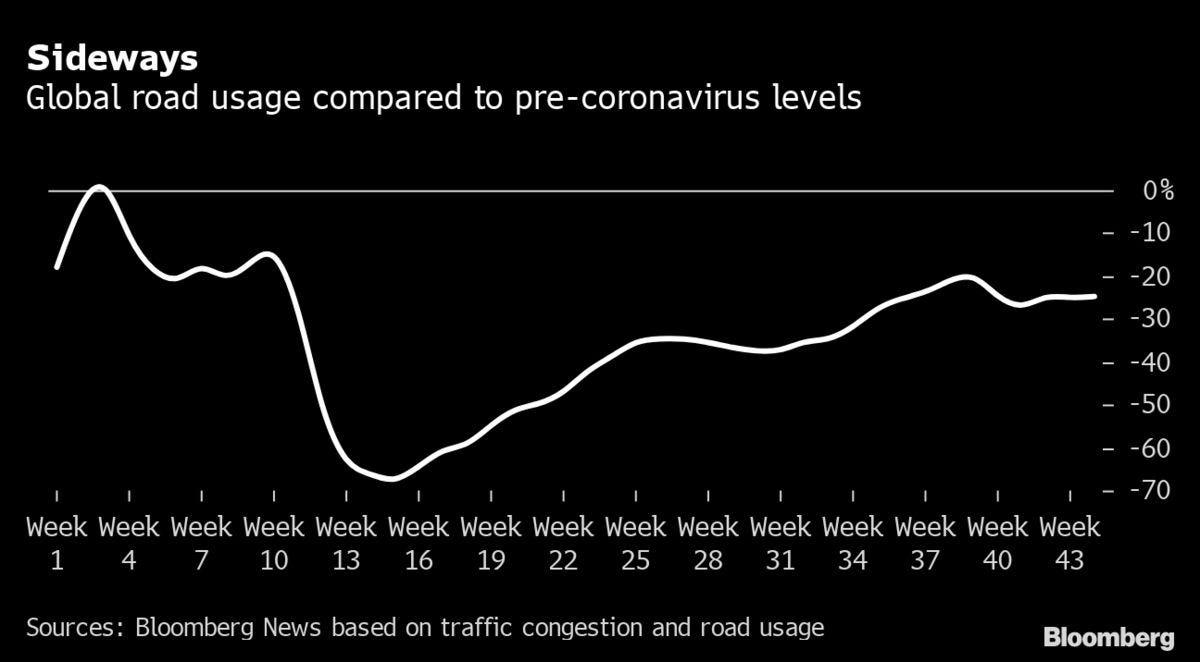

Then you get to the demand side, which I’ve repeatedly stressed is both very uncertain and mostly grim. Road fuel demand globally is still down significantly and oil demand’s been weaker than expected prior to the Pfizer announcement:

Russian policy is picking the worst moment to prioritize greenfield investment. The logic, however, is pretty clear: it’s stimulus. By extending support for things like Vostok Oil, they can create more short-run demand for goods and services and use loans subsidized and/or backed by the state to keep it going without tapping money meant for the budget. The current price rise is just a stumble towards hope. Russian firms will be contending with lower for longer a lot longer than they every admitted in. the first place.

EM, Not Coming

The growth of passive investing isn’t going to slow down given active managers of capital have struggled mightily during this latest crisis to beat funds and related passive instruments that track aggregate indices or an individual sovereign’s debt issuances and so on:

It’s interesting to consider just how frequently those in finance misunderstand the political institutions they’re effectively gambling on. This quote has always stuck with me, from a 2017 Washington Post op-ed about Trump being out of place in D.C. As someone born in the D.C. metro area who then moved and grew up in Chicago, but still feels at home there, it bears repeating when thinking about the financial flows of the future:

“Washington understands New York better than New York understands Washington, much as the South understands the North better than the North understands the South. In the same way, out in flyover country, America’s working class understands dinner-party liberals better than the liberals understand the working class, if they even know it exists.”

The relentless rise of passive investment is a curious one institutionally, one that would seem subject to the reality that even the most informed market participant is in an utter fog about the decisions being made that are going to affect any range of policy or business outcomes.

By Wigglesworth’s estimate, there are now over $20 trillion invested into funds, indexes, or else internally managed like either of those two without being identified externally as money that is passively invested. Where active managers sell you on their prowess and predictive power, passive managers sell you on low costs and matching the market. But that also means that, in tandem with the rise of retail investors using apps or home time to trade passive instruments, more and more people trying to actively manage their wealth (if not their specific investments) don’t really know the nitty-gritty of what they buy. That’s a long-term trend, but if I were to open up Robinhood now and look for a Russia ETF, even if I dug up its details, I might struggle to fully grasp what I’m holding and I’m a Russia specialist by background.

The reason I find this so interesting is that managers overseeing passive funds wield an immense amount of power beyond that held by active money managers given that they manage products that are more readily accessible to a wider array of potential investors who, realizing that bank deposits are largely worthless in a world of zero or near-zero rates and seeing how bad things are for them otherwise, might as well take a punt. I don’t have any insight into what said managers are looking for when they track companies and bonds in, say, Russia or the CIS, but I do know that the growth stories being sold to investors rarely look so rosy when you look under the hood. Russia’s been underperforming for a very, very long time, and aside from sovereign debt, most EM portfolios looking to generate higher yields over stability in the coming are going to have less of a reason to invest there, save as a hedge. Russia’s own pension funds lag, and it may well be that it needs to up its game when it comes to passive investment. But as mentioned yesterday, that likelier entails capital outflow if incomes rise than domestic investment because of the risks and frequently poor returns. And it doesn’t necessarily help with capital inflows if John Q Public has an app and, licking his finger to test the wind, gets a bad vibe about a Russian ETF or equity because of a news story that day.

The risk of passive investment is, logically, that as more people do it, more people are prone to panic selling or euphoric buying whenever the market gets turbulent. I wager that Russian financial markets aren’t going to see as much action from the underlying trends as they could, yet another reputational risk premium. That’ll spillover into how investors view their prospects and the feedback between financial markets and pressures on Russian policymakers and firms, especially as the energy transition destroys equity value in the country’s largest industries. Saving bonds at all costs doesn’t help people trying to build a nest egg in their 20s, only in their 60s. And half of Russian men are dead by 65 anyway, so no wonder the economy isn’t well-designed to allow for savings accumulation…

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).