Top of the Pops

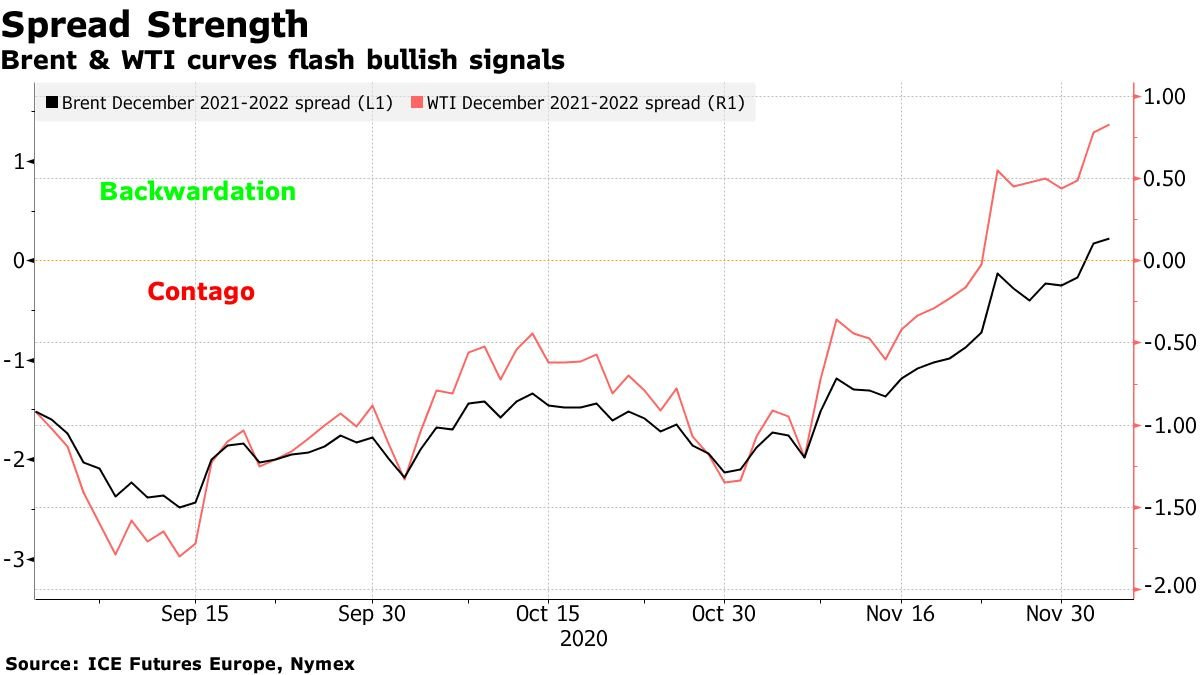

OPEC+ split the middle of some contentious negotiations to arrive at a deal to gradually raise output come January by 500,000 barrels per day, with Russia taking 125,000 of those barrels. Saudi Arabia definitely didn’t want the risk, but the UAE’s recent oil reserve expansion and drive to be able to produce more have upset the balance within the group and, I think, signals what could be a major shift in mentality for OPEC+. Saudi (and initially Russian) calculations for cuts were rooted in privileging price over market share, whether to save budgets or to preserve foreign currency earnings and bank sector liquidity. In a world of stagnant and declining demand, market share matters far more since downside demand pressures make it exceedingly difficult to sustain price levels through market intervention. The announcement lifted prices — Brent started out this morning shooting to $49 a barrel and will probably end the day close to $50, but the real story there is the futures market flipped back into backwardation for Brent through 2023. The market’s pricing futures lower than spot prices or short-term contracts, which either means everyone suddenly wants oil now in a bullish sign for the short-term market as that means that storing oil is worth less than selling it now:

Watch for how long backwardation sticks. I’m curious how the market is pricing future supply vs. demand balances and how much the return to backwardation is about comparative short-run strength vs. expected weaker underlying future demand compared to still plentiful supply as it is about the cuts this year working psychologically no matter how mixed the news from storage and products markets actually is. Remember, crude oil is priced through the value of the refined products it becomes, not through its own end use. Topline crude prices reflect what refiners are paying to create the stuff consumers actually want. Demand and shortages can reflect longer periods of idling refining capacity and changing refining slates for products as much as curtailing crude output. The oil market remains a demand story.

What’s going on?

The cabinet just passed on a new bill to the Duma stipulating tweaks to the law governing ports that private investors provide investments and credit guarantees “commensurate” with levels of state investments into Russia’s ports and port infrastructure. The initiative, led by MinTrans, is an important one to track. The state is effectively trying to force private businesses to borrow more to cover shortfalls driven by fiscal consolidation. The mechanism to meet these requirements is still being clarified, but I think it’s indicative of the post-COVID social contract with Russian businesses. Russia’s hoarding of currency reserves is going to be used to back a continued credit expansion driven by firms and consumers. That entails greater levels of financialization in the economy as well as a slight shift in the relative power of large firms and investment groups to lobby for exemptions, aid, or else curry favor. This phenomenon isn’t new, but more intense since 2014 given austerity measures and only getting stronger.

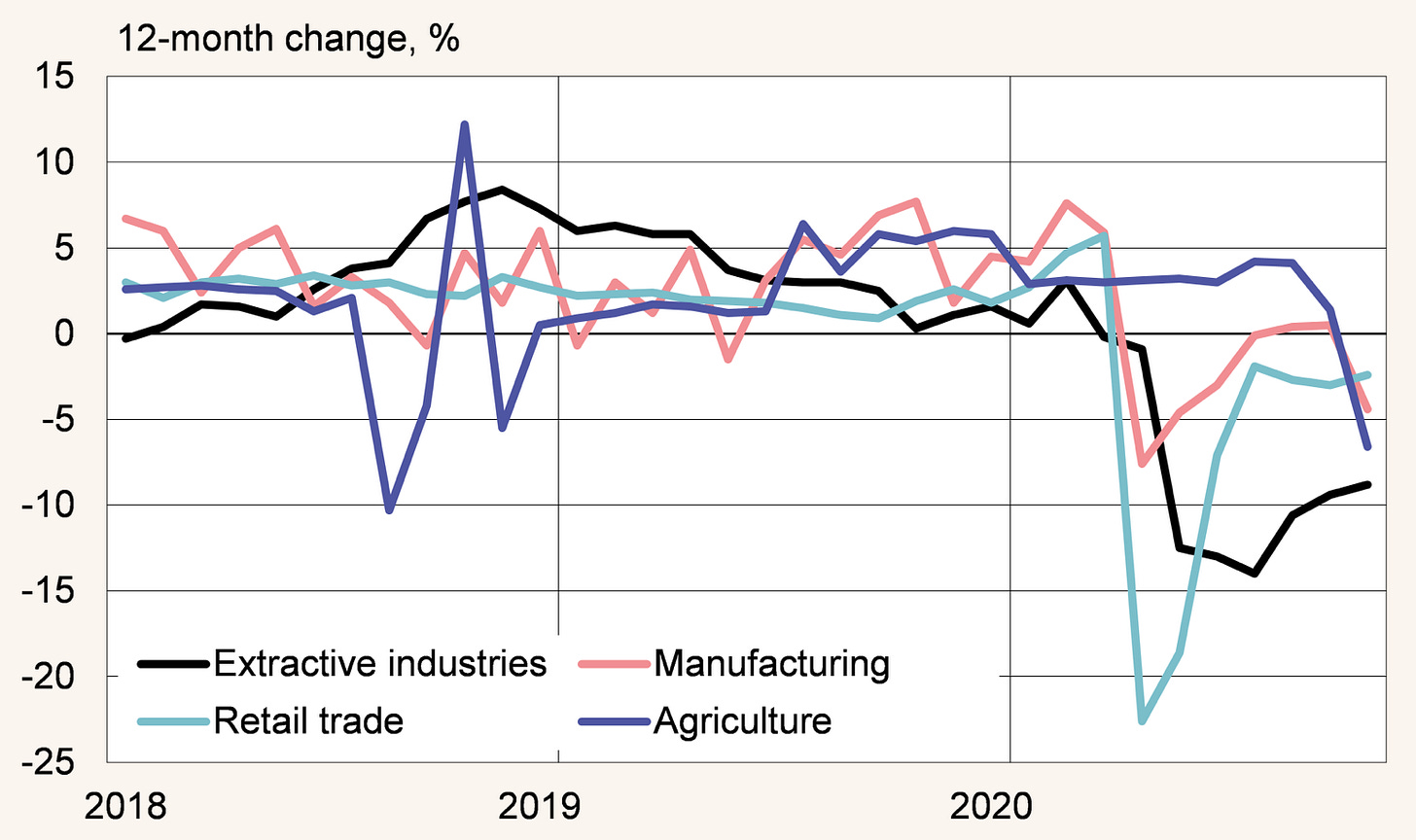

Elvira Nabiullina is carefully managing business expectations that COVID-related measures easing small businesses’ access to credit will continue into next year only if the situation across the broader economy develops 'unpleasantly.’ This is way different than the Draghi playbook: “whatever it takes . . . only if we absolutely have to.” Since the start of 2020, the CBR’s credit portfolio with smaller firms has grown 15% in size and 64% in terms of the number of borrowers (about 450,000 firms now). Her approach is marked given poor October numbers from manufacturing and agriculture:

The gameplan is clearly to keep constant control of the inflation expectations narrative while offering some kind of reassurance to business. Unfortunately, I think the CBR’s in over its head when it comes to policy room for maneuver. They better hope the current oil price rally sticks.

The updated special investment contract mechanism (SPIK 2.0) has finally launched, providing investors a list of 600 technologies for whom investments into the localization of production will receive long-term tax breaks. Oddly enough, gas turbines — a point of contention ever since supply chains from Ukraine were interrupted in 2014-2015 — didn’t make the initial list but could be added. The tax exemptions offered include: the nullification of regional taxes on profits, reduced land, property, and transport tax payments, and reduced federal taxes on profits and apply to investments of at least 750 million rubles ($10.1 million). Investors then can lock-in these rates per the contract for 15 years, which rises to 20 years if they invest more than 50 billion rubles ($673.4 million). The initiative is an inefficient, but necessary way to insulate investors from constant policy risks for their returns. I’m incredibly skeptical it’s going to have much of an effect for the simple reason that Russia’s domestic market is no longer as attractive as it once was and the formalized costs of doing business per the tax system aren’t the main barrier to investment in Russia. They’re rather rule of law protections and corruption.

Rosstat from 2Q shows that the population living below the poverty line in Russia rose by 1.3 million people during the first wave, reaching 19.9 million total or 13.5% of the population. That’s 1 in 7 Russian citizens. But those figures include the (relatively) paltry social support offered by the government worth about 359.4 billion rubles ($4.84 billion). That’s a big chunk of incomes made up of one-off or temporary social transfers that won’t be there for later data. It’s pretty clear that the 2018 May decree to halve the level of those living in poverty in Russia by 2024 is completely out the window unless spending picks up and the 2030 target, while achievable, is still going to be difficult without more evenly distributed economic growth. When you factor in that the income level for pensioners is only 76% that of those who are working age, the picture looks a lot worse since the country’s aging, wages aren’t rising enough, and it’s not like the working-age level of 12,392 rubles ($167) a month is great to begin with. The measure is logical given relative costs of living, but it speaks volumes to how the state is trying can better manage the growing fiscal burden of handling a larger retired population by fixing the reference levels for different social programs to a considerably lower income scale.

COVID Status Report

The last 24-hour caseload came in just above 27,400 with 569 reported deaths. Moscow’s stuck in neutral still waffling back and forth between higher and lower daily numbers while the regional figures actually suggest the rate of increase might be about to rise:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

Moscow has launched an electronic registry for those set to receive free vaccinations and it will be widened accordingly as more doses are rolled out and the state’s promise to make it available to every Russian citizen free of charge is carried out. From the Central Bank to Putin to the social bloc and more, everyone’s been forced to go all-in on the “vaccines will save everything” narrative. The regions are where the panic is still. RBK has again pulled its regional heat map (and that’s after adjusting the colors in a one-off to make it seem like things were better than they were). As of Dec. 1, 17. regions had less than 5% of their cots available for new incoming COVID patients. It’s a race against time.

Aging Gracefully

One of the main recurring arguments for green stimulus from the 2020 presidential race in the US, from the COVID responses of different political factions and parties across the OECD, from economists pushing the idea of a “Green New Deal” its that it could create millions of new, sustainable jobs and help address a long laundry list of social ills. It’s a heartwarming tale that’s told, one where human ingenuity and the desire to save the planet lead to more just and equitable outcomes. Unfortunately, it’s far from that simple, not that clear that green stimulus ends up fundamentally altering underlying growth, and requires more than a few policy leaps of faith. It’s important to pause and think it through because of the frequently contradictory geopolitical and market narratives that can emerge from the process.

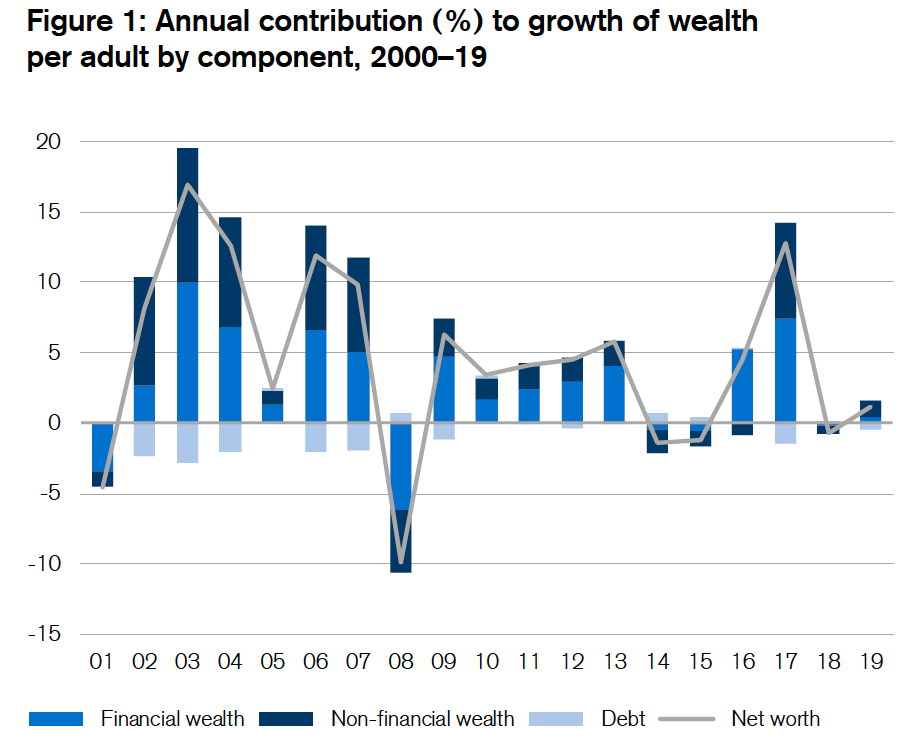

The biggest problems in assessing the effectiveness of green stimulus starts with but go beyond what I alluded to in yesterday’s column: changes in energy costs significantly affect price levels, races to technologically innovate make trade agreements and import substitution more important for price levels and costs of inputs, most models offer highly aggregated views of ‘green’ job creation, and many struggle to factor in supply constraints that exist or would emerge. TL,DR: no, green stimulus doesn’t de facto lead to massive growth gains. But at an aggregated level, the good news is that the global economy has the financial firepower needed to make the energy transition a reality. The OECD estimates that annual investments worth $6.9 trillion are needed through 2030 to be on pace to meet climate goals keeping warming under 2 degrees. The biggest issues, however, are creating the right infrastructure of long money at low rates and the right investment grade projects to be able to absorb that level of investment effectively and relatively efficiently. That’s akin to annual infrastructure spending worth about 7.87% of global GDP as of 2019, a share which will decline annually (though would be higher for this year and probably next year) as the global economy returns to broader growth. That figure is all the more manageable when you consider that global wealth was worth an estimated $360 trillion as of mid-2019 (h/t to Credit Suisse). However, the rate of wealth growth has dropped considerably since 2008 and tracks closely with global GDP growth:

As we can see, global growth has declined and with it the growth rate for the creation of new wealth. There’s loads to untangle here, but suffice it to say that I lean towards the school of thought that the global economy has suffered from systemic underinvestment due to global imbalances, the accrual of rents to an ever shrinking pool of firms in different fields with greater pricing power, the loss of labor’s bargaining power to affect wages (which coincidentally disincentivizes firms to invest into enhancing efficiency of production), cuts to state R&D budgets and more. The energy transition is fundamentally about mobilizing untold masses of capital to correct the deficiencies and problems caused by underinvestment aimed squarely at making energy processes and consumption emissions-free or minimally polluting and, when possible, fully sustainable. That’s where demography and the need for “long money” from central banks, fiscal policies, and the private sector come into play.

Consider the following. The top 7 pensions markets in the world account for about 92% of all pension assets under management, worth around $46.7 trillion. The US alone provides 62% of the pension capitalization for the world’s 22 largest markets. Between them, there’s plenty of room to cover a large part of the OECD’s estimated capital needs. Green investments require long time horizons because so many of them entail higher initial sunk costs recouped over the operating life of an asset or, in the case of technological breakthroughs, lots of high-risk spending on research with unclear commercial gains to be realized if deployed. The UN estimates the global population aged 65 and up will more than double between 2019 and 2050:

The global population is going to skew older, which means in more and more markets, there’ll be a need to develop suitable pension systems buying equities, bonds, and related instruments to provide stable, long-term returns:

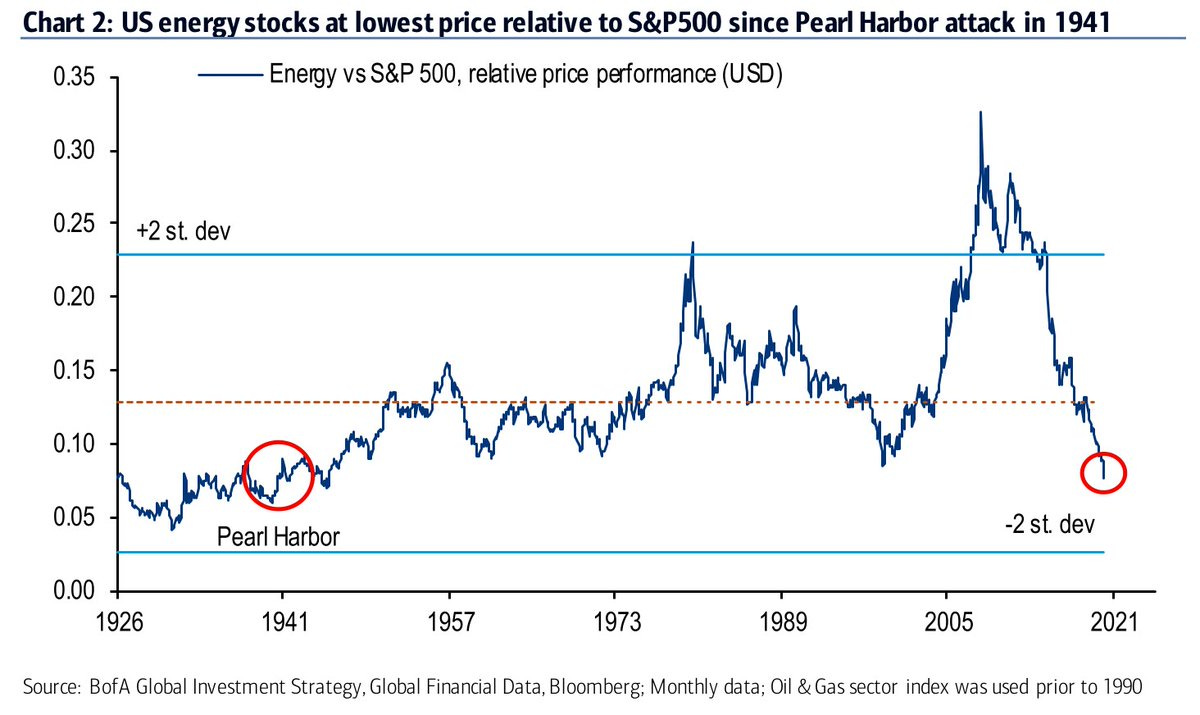

The US can lead the way in rolling out specific assets to be bought by pension funds since persistently low and negative yielding debt creates what Former pensions minister and peer of the House of Lords, Baroness Ros Altmann has described as “return-free risk.” If sovereign debt is not an attractive source of stable returns, the only alternative is to deploy capital into lower-risk vehicles that, ideally in this case, actually increase net investments into productive capacity by supporting green infrastructure, public transit, and more. In the aggregate, there is more than enough wealth in the world and a rising number of people retiring or nearing retirement in need of fixed-income support or else stable sources of income. This pivot is taking root in the UK, for example. Before the Russia-Saudi price war in February, US energy stocks were at their lowest price relative to the S&P 500 since Pearl Harbor was bombed:

Green investments offering returns and risks like utilities are the way forward. But if pension funds are going to be a crucial source of plugging funding gaps for green infrastructure development and green stimulus plans, then energy market coordination and regulation is going to be absolutely crucial to avoid asset bubbles that could cause their own financially-driven boom and bust cycles that used to dog oil markets before the Texas Railroad Commission modeled quotas and related output controls to stabilize prices, an approach that OPEC would emulate when it formed. One of the risks of an aggressive green energy transition in the US and broader OECD noted by Jason Bordoff, an Obama White House alum from Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, is that the current OPEC+ producers actually increase their relative power over oil markets as zero-emission rules hurt production elsewhere.

Denmark just announced it’s ending all oil & gas exploration in the North Sea and hoping others follow. European aeronautical giant Airbus is now setting itself a 5 year timeline to achieve hydrogen-powered, emission-free flight. These augur a new wave of similar types of announcements intended to rapidly accelerate the investment cycle into greener tech and energy while effectively tying the hands of policymakers by locking them into a set of economic policies requiring them to grapple with emissions more seriously. But in the meantime, even with stagnant oil demand and its soon-to-be decline, we’re still consuming tens of millions of barrels of oil every day in most net-zero scenarios we can envision. What else are we going to make plastics from? If, and this is a big if, the Biden administration imposed punishing restrictions on shale output on non-federal lands through environmental regulations and the like, then you’d suddenly see more pressure on natural gas markets and prices and, again, more money for Gazprom and Russian LNG. Greening has to be balanced against returning the oil market to its more oligopolistic past.

Power markets, however, are highly regulated in developed economies, often with incentives built in to balance supply with demand, to distribute costs between industries and residential consumers depending on various social contracts within economies, and to try and steer capacity investments into cleaner options. But electric utilities specifically have seen declining returns on equity since the 80s, according to S&P Global Platts, because of lower interest rates and the rise of investor protection mechanisms designed to provide automatic adjustments when return targets aren’t meant, presumably somewhat linked to the declining cost of borrowing to cover shortfalls:

Swapping sovereign bonds with green utilities will play an important part in the energy transition story, and it’s a trend to follow because of how differentially it can impact exporters’ fortunes. If Europe manages to mobilize its wealth and turn its aging population into a structural source of long-term financing to sustain the transition, Russia’s current account and export strategy are going to have to adjust quickly. Conversely, Russia could use the same strategy to further its own economic development as insurance and related financial markets in Russia grow and go in search of financial assets to acquire to generate interest and dividend returns. This is an area where the greater financialization of the Russian economy would help it move past the highly extractive nature of its political and economic institutions. Green energy simply isn’t that good for rentiers, especially when it becomes more decentralized. If Keynes’ injunction to euthanize them has any meaning for Russia, that’s a pretty good place to start.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).