Top of the Pops

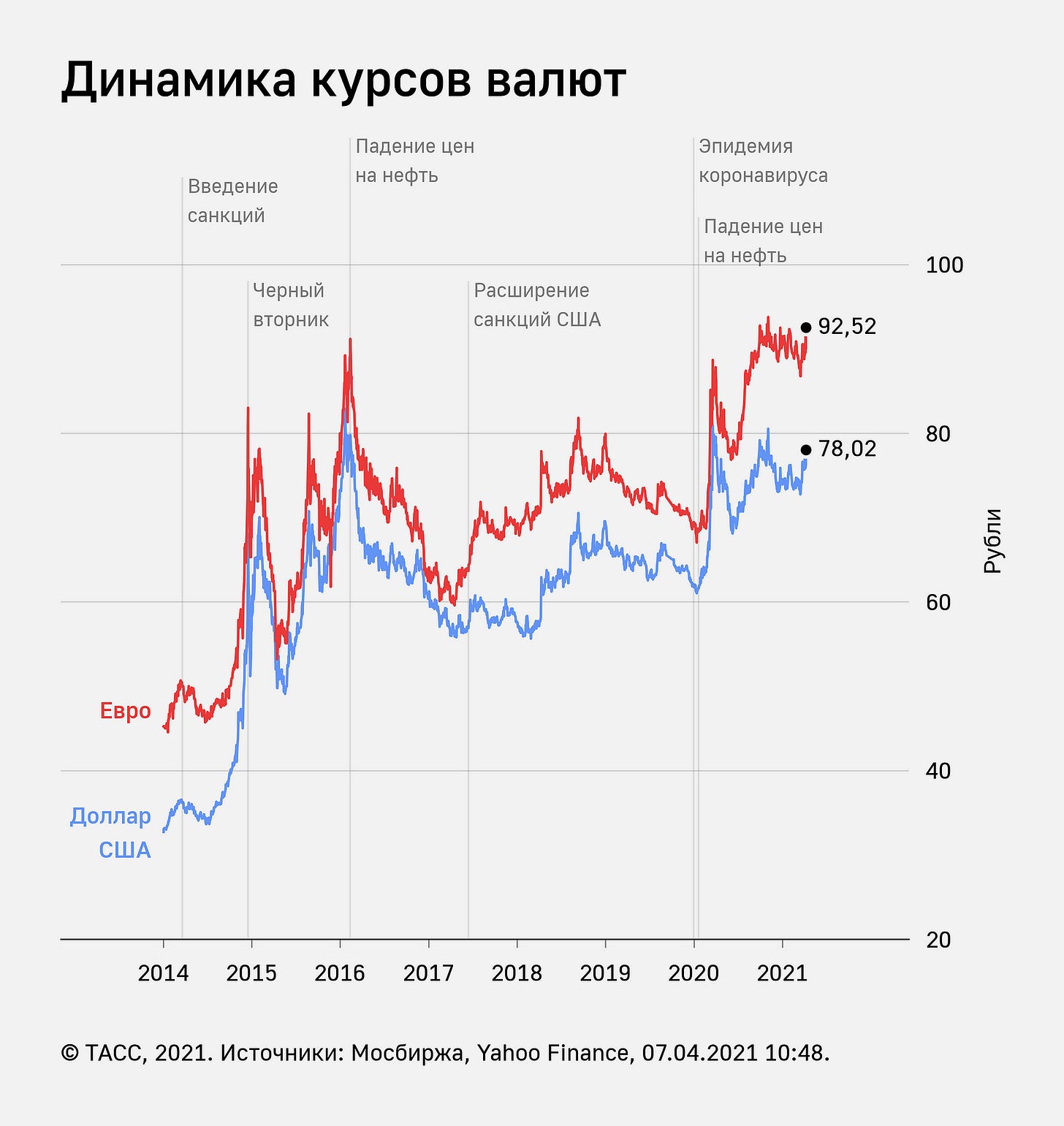

The ruble broke 78 to the US dollar for the first time in 5 months as more people fret the latest announcements about military preparations near or on the Ukrainian border. Yesterday, the Ministry of Defense noted that inspections were going ahead as per preparation plans, which hasn’t exactly calmed anyone in Washington as to Russia’s intentions:

Red = Euro Blue = USD

It’s also interesting to note that the Euro’s exchange rate level is higher than the sake in 2015-2016 in relative terms than the dollar, which could mean a few things — one that comes to mind is that more imports are being invoiced in Euros and exports to Euro-using economies are lower since oil demand in particular is weaker in Europe. But it’s something to watch since the attempts to reduce the dollar’s share of Russian trade and financial transactions end up altering the effect on relative exchange rates over time. At the same time, China has once more rebuffed Russian efforts to shun the US dollar and use Russia’s own version of SWIFT. Turns out that the US dollar is a lot better for one’s own macroeconomic management if you’re a leading exporter with a soft currency peg or managed exchange rate against the USD. Currencies are always political, but there’s no getting around the supreme liquidity and efficacy of the US dollar no matter how much Moscow wishes it could do so. If one assumes that Russia’s coercively signaling with the new buildup, it’s already carrying an economic cost. The recent fall against the USD and Euro correlates to market fears that Russian military action will bring harsher economic retribution from the US. The expectation at the moment appears to be a continued weakening of the ruble against both currencies, which will then filter into Russian households by raising import prices for industries that aren’t exporting. Turns out that demonstrations of ‘dark power’ may well worsen the inflationary pressures worrying the Kremlin ahead of the September elections in yet another example of security policy generating negative economic externalities and effects for the regime. Talking up the nation’s power to act militarily if need be is talking down the ruble in this climate.

What’s going on?

I missed this last week, but MinEkonomiki is pushing forward another attempt at concessions reform. The main rule change would stipulate that the state can’t finance more than 80% of a concession project, a seemingly arcane but massively important change meant to resolve an ongoing fight between MinFin and MinEkonomiki that dates back to Maxim Oreshkin’s tenure as Economy Minister. Back in 2017-2018, the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service and regional courts in Russia moved to nullify a series of contracts awarded on a contract basis because they were 100% guaranteed by state money, which in their view meant they should be procurements instead. The new proposal would limit those cases by mandating the government specifically decide on the relevant cases where that would apply and only make such decisions when they’re a socially important project. Since 2015, the value of projects awarded on a concession basis has grown to regularly exceed 350-400 billion rubles ($4.5-5.15 billion) a year, but been declining since 2018 when that legal fight broke out ahead of Putin’s 4th inauguration. Concessions agreements are, in theory, a way to encourage more private investment by promising investors terms and setting (relatively) inviolable legal agreements. But Russian concessions law is a disaster and riddled with regulatory requirements for things such as user tariff rates that have rendered its ability to take advantage of China’s infrastructure expansion across Eurasia broadly moot, save for some investment plans on the Trans-Siberian and Baikal-Amur Mainlines with RZhD. But the 80% limit figure is likelier to crimp construction than crowd-in private money, a disaster in the making if it ends up affecting concessions to build schools or other basic pieces of social infrastructure since private money knows the returns are terrible. This is a prelude to either a radical escalation of strong-arming businesses locally to invest or else a further collapse in investment levels because only state money and guarantees offer adequate assurances now that the state has to de-risk the private economic activity it’s increasingly counting on to make up for its thriftiness. One can imagine the incoming jokes about locking up Reshetnikov for this if it goes pear-shaped.

The mortgage lending boom is slowing down based on year-on-year figures for volume of credit lent and number of mortgages issued. Worth noting, however, that even with the slowdown depicted in the following graph (% YoY), the absolute level would remain higher for awhile and take a real contraction to ebb away:

Blue = growth of mortgages issued Orange = growth of volume of credit

The February data is where the beginning of a slowdown is most noticeable — the number of loans issued was up 28% YoY vs. 35.1% in December. And clearly the relative increases will decline as we enter months that correspond to the period when the program really got underway last year. But it’s surprising to see just how much the figure is still rising at a time when consumption figures haven’t shown a corresponding level of recovery for other goods or services and savings rates are still up. That suggests that people still see purchases as a means of hedging against inflation since prices keep rising as well as getting onto the property ladder with what they have while forgoing other consumption. Or else it’s just the better off swooping in and buying properties before deficits of new housing get too acute. Mortgage issuances hit 4.3 trillion rubles ($55.17. billion) last year, a record high equivalent to the value of 8.1% of labor’s share of the national income in 2020 in current prices. This is a huge diversion of spending power that may trigger new builds and construction sector growth as well as create some wealth on household balance sheets, but it’s going to eat into other types of consumption so long as real incomes don’t rise.

The EAEU’s antimonopoly commission has written to major taxi aggregators in Russia, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Belarus, and Kyrgyzstan about price formation — it appears that aggregators are price-fixing (using surge pricing and other means via algorithm) in a manner that maximizes their profits rather than those of the taxi drivers and hurts consumers because there aren’t any alternatives to compete against. The aggregators are basically sharing a pricing system instead of competing. Welcome to poorly regulated markets the hard way, guys. The commission has targeted Yandex.Taxi, Uber, Maksim, Gett, and Sitimobil. The Federal Anti-Monopoly Service in Russia looked into this in 2020 and didn't find any legal violations. This is an interesting development because it’s a clear case where the EAEU, which has on paper unified and harmonized all taxi aggregator regs/markets between member states, actually has some power to compel regulatory action and is doing so despite the parallel body in Russia not having found a problem. I don’t necessarily expect it to go much further, but I do think that it’s a welcome sign of life that the EAEU can exert some pressure on members to harmonize regulations and promote competition. There’ll be a meeting with representatives from the companies listed in Moscow on April 13. I’m hoping a substantive announcement follows, if only because it would pose a form of constraint on Russia’s ability to use its size to force other member states to adopt regulatory regimes favorable to its own companies.

Russia’s clothing retailers are breathing easier now that demand in March rose year-on-year in Moscow and St. Petersburg, the two biggest, richest markets in the country. Still, sales are lower than they were in 2019 and broadly rising prices will crimp full recovery to 2019 levels without higher earnings. In Moscow, shoe and clothing sales were up 10% and 20% respectively YoY while those figures were 11% and 40% in St. Petersburg. But nationally, demand for both was down 15% and 17% respectively in March. According to data from Evotor, that falls to 30% and 50% down against 2019 levels. The OR Group, one of the largest retailer groups in Russia, doesn’t expect to return to 2019 financial levels for earnings for another 2 years. There’s an overall feeling that consumers are more price sensitive now and less likely to impulse buy, which corresponds to the weakening of the ruble and its impact on import prices. Cotton prices have risen 30-35% since the start of the year, feeding into consumer prices as well. Inferring from Kommersant’s writeup, 2019 clothing sales were worth 2.23 trillion rubles ($28.7 billion) which then fell 25% in 2020 to 1.71 trillion rubles ($21.97 billion). The most optimistic scenarios show demand recovering to pre-crisis levels by fall 2023, with pessimistic ones marking 2025 as the date for recovery. That’s atrocious and a leading indicator for just how weak consumer recovery and Russia’s ‘diversification’ really are.

COVID Status Report

In the last 24 hours, there were 8,294 new cases and 374 recorded deaths. The RBK highlights the gamesmanship of the stats put out by the Operational Staff since the crisis hit using 2020 data for April-September. They didn’t want to really scare anyone but pulling out further stats showing it getting worse . . . Top is general number of deaths of people diagnosed with COVID, middle is those who died with COVID listed as the primary cause of death, and the bottom is the Operational Staff figures:

One of the worst parts of covering the Russian economy and making sense of macro, its relationship to politics, and so on is that Russian data is terrible. It’s flimsy, frequently changes methodology, riddled with capacity errors or gaps, or else outright political and yet has to be used analytically. The current daily death data is still at a level seen in late November and not falling significantly. Couple the COVID manipulations with attacks on the veracity of inflationary readings and you realize that the available data about recovery in business sentiment, for instance, is less meaningful the less reliable other indicators become. How can anyone expect investment levels to rise when the rate of return on investment is itself political and SOEs can attack journalistic investigations using their own data to reveal that state money is inefficiently being spent? COVID news in Russia is increasingly “boring” because it’s increasingly divorced from the statistical picture we have, some of which can be explained by hospitals adapting to treatment needs without needing special facilities (the decline in beds available for COVID patients isn’t all bad I’d wager). Behind it, however, you get the sense that post-crisis, some data will be even less reliable than before despite the government’s attempt to harvest it so as to improve outcomes.

Breaking Windfalls, Breaking Technocrats

It seems that the management team around Andrei Belousov is pushing for a round of windfall taxation on metals firms to cash in on rising commodities prices and the initial tailwinds of the energy transition to raise funds for construction subsidies doled out to MinStroi to reduce the effects of domestic price inflation for inputs. MinPromTorg put forward two proposals:

Set indicative prices above which firms selling domestically or for export are forced to return some of the additional margin, likely via a tax, that would be recycled via a subsidy

Increase the tax rate and use the additional tax revenues raised to compensate MinStroi so that projects can absorb the higher material cost.

The management of commodity price cycles continues to haunt Russian economic policy and now seems set to hit metallurgical firms as metals prices trend upwards. For reference, here’s the IMF’s commodity index data measuring relative price levels for all metals, precious metals, base metals, and the all commodity index going back to Jan. 2014. 2016 = 100:

As we can see at the tail end of 2020, there’s a huge spike in the base/all metals indices at the same time the returns from Russia’s goldbug obsession with gold mining stopped paying off. MinPromTorg’s proposals are elegantly simple, but reflect a broader choice among policymakers in the current pre-election policy environment to try and kill the effect of price levels on demand to keep the recovery going instead of providing demand stimulus to encourage investment into new production. For instance, in February, a 5% export tariff was slapped onto scrap metal to try and curb exports because rebar prices — think the steel bars or mesh used to reinforce concrete and masonry as a tension device to manage weight loads — were rising and scrap metal accounts for 80% of the end price of rebar. Now MinPromTorg wants to limit scrap metal exports to the Far East and Kaliningrad to kill exports by raising logistical costs. Instead of letting the surge in housing prices subside by a rise in prices to spur more construction investment, the aim is to try and control prices to maintain existing investment plans without adopting better fixes such as changing planning permission requirements at the local level to reduce the incentives to ‘bank’ land for future development and extract rents from construction. Letting prices rise too much is admittedly a terrible approach in general but more logical when everyone expects monetary policy tightening, real incomes are not yet recovering, and private investment levels need to adjust as well as housing stock deficits emerge.

By recycling the windfall from the metallurgical sector into housing subsidies, MinPromTorg’s proposal would effectively keep demand going, but reduce the profit margin for investment into new marginal production of the metals being consumed. The effect would be that consumers might be spared more pain — I’m skeptical because investment levels currently depend too heavily on state spending — but producers have less reason to invest more, which of course affects the global market since these are fungible commodities with a very long shelf life. In time, that will diminish these firms’ export earnings and negatively affect the current account surplus. It’s hard to imagine metals prices falling much anytime soon. If less new production comes onstream, you get pricing pressures later on recycled through a shortage of production globally at a time when demand is rising. So long as the aim is to prop up construction via subsidy, the mechanics aligning prices and supply are thrown off and the federal government, unable to move local interests to improve the permissions process or draw in private capital that could net a better return, is stuck managing supply. This is a problem touching all the regions, too, not just the biggest cities.

Kaliningrad appears to have been hit hardest by housing price inflation in 1Q — prices rose a whopping 10.5% to 67,700 rubles ($872.65) per sq. meter. They were up 7.17% in St. Petersburg to 144,600 rubles ($1.863.27) per sq. meter. Nizhniy Novgorod, Ulan-Ude, and Sochi all saw price increases above 8%. The ongoing surge is having such a drastic effect on household finances that the Duma had to rush through a reform to simplify the process to mark tax deductions for home purchases and mortgage interest payments. 1 million sq. meters of new builds for housing were finished in Moscow in 1Q, a reflection both of the urgency of the housing price situation, potential migration pressures if jobs are available in Moscow before other cities and people are working more in mixed arrangements blending freelance stuff from home with office gigs, and Moscow’s greater capacity than any other region to finance and push through these types of works. That’s 1/75th of the national program target set from 2020 into this year just in Moscow just in 3 months. At the current pace, which may well quicken ahead of the election, Moscow would be contributing over 5% of the mandated housing stock expansion assigned to MinStroi and national targets for the year. That figure is too low given its economic centrality, but it’s better than nothing.

In a move that is simultaneously unsurprising and quite a shock, Bank of Russia head Elvira Nabiullina is calling on the government to lift price controls as soon as possible because they’re distorting pricing indicators and preventing investment into production. Her warning comes as a shot across the bow at the economic tinkerers in the presidential administration assure Putin that all is copacetic. Per his own words, “we’re talking about restrictions linked to the extraction of excess profits. There’s nothing to worry about here.” That his economic team feels they can assess what qualifies as ‘excess’ profits for exporting industries exposed to international pricing pressures is laughable. Nabiullina’s always been against these measures, but the pressure’s on her now because they also undermine the efficacy and credibility of monetary policy as an instrument to fight inflation. I disagree with the decision to hike rates because inflationary pressures are either imported via international pricing channels or a result of domestic supply/demand imbalances that can be better corrected through sustained demand leading to higher investment rather than cutting it short. But still, it makes the Bank of Russia’s job much more difficult when consumer prices no longer correspond to producer price levels or else are being subsidized by a rising tax burden on sectors that could otherwise invest into more productive capacity, which would then lower price levels.

The escalating criticism suggests to me that the technocracy that has run economic policy with relatively limited interference from Putin’s team is breaking down. MinEkonomiki is arguing against the introduction of any damping mechanism-style duties on exports of metal products because they would entirely ineffective with an open market and would likely lead to deficits of products as companies’ profits fall. Instead, the ministry rightfully argues that consumers have to be supported. That approach doesn’t contradict MinPromTorg’s idea to use a windfall tax provision to provide subsidies. Economic ministries and institutions have always disagreed in Russia and fought for their respective lobbies, power bases, or else ideas. But what’s changing is that you can infer, reading between the lines, that only the ideas the presidential administration wants to hear are getting through. No serious economist I can think of would suggest that an arbitrary export duty on a globally traded good sold at spot prices would positively affect price, supply, and investment levels in an economy that can openly import that good if it can’t produce enough of it (and also happens to run a large trade surplus more broadly because of how it suppresses domestic demand).

The longer the shift in approach lasts, the worse the damage will be to existing political arrangements. Once a price control is introduced, you not only affect the relationship between price, supply, and investment. You create a new political context whereby intermediate or end consumers have every reason to want to maintain price controls if their own interests are furthered by it. The attempt to centrally administer prices is also feeding the populist impulse of some elected officials at the local or regional level or in the Duma. For instance, airfare started to tick up noticeably in March, so naturally you now have Duma reps telling the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service to look into it and do something. Russia’s political institutions, even if they’re facsimiles or performative theaters, are clawing away more of the independence traditionally reserved for economic policymakers since Putin came to power. Even Mishustin’s comparatively benign attempts to improve consumer protections and licensing regulations in important sectors betray a lack of awareness of economic consequences. Doctors at private clinics are warning that if licensing requirements are tightened to require more experience working in the medical care system, private medical care costs will go up, further hurting Russians who seek care outside of the state system due to its own failings, capacity constraints, and institutional problems. Some of that is completely normal lobbying, but it’s exactly the kind of problem small businesses struggle with in countries like the US.

Every new proposal lowering a cost for a consumer raises a direct cost or an opportunity cost for a producer while altering lobbying interests for further policy changes. If Nabiullina is this concerned about the regulation of prices, there’s fire. The latest CBR review of credit restructuring shows that the number of credit agreements whose conditions have changed for borrowers rose 24% in March. It’s exceedingly difficult to get a handle on what to do to contain potentially building financial risks if monetary policy is increasingly detached from consumer spending levels. Mishustin’s running into some of the same economic challenges that beset reform efforts from the late Soviet period — there’s no way to compensate the losers adequately in a system where access to state resources, state-generated rents, or price controls during a period of stagnation and lower earnings off the primary export goods (oil & gas) without a large rise in borrowing and changes in the power of interest groups that would threaten the structure of the political system. Recycling windfalls worked when there was still slack capacity in the Russian economy to unlock as oil rents climbed higher. That’s not been the case for 8 years now. Recycling ends up taking money out of the economy in the longer run by constraining investment at the same time it maintains demand levels. History is most certainly not repeating, but it’s getting closer to rhyming the longer this continues. The technocrats have ably kept the system together so far because of the degree of independence afforded them. That era seems to be drawing to a close, or perhaps more accurately, the degree of independence afforded them is being redefined. ‘Manual control’ becomes automatic when the brakes on prices fail.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).