Top of the Pops

Word that Novatek is joining the race to ‘green’ its production of LNG is welcome knowledge and it’s all thanks to buyers. Counterparties in Singapore looking to scoop output from Yamal LNG and Arctic-2 LNG are asking how dirty the fuel that Novatek’s pushing, part of an accelerating shift among consumers eager to incorporate emissions externalities into their business rationale. Referring to Wood Mackenzie’s emissions benchmarking tool, LNG is one of the most emissions intensive forms of production, trailing only heavy oil and oil sands:

Asian buyers are already shopping based on lower emission rates, which has cost Novatek some contracts. However, it did close a long-term deal with China’s Shenergy Group Company a few weeks ago and is hoping to take a final decision on investment into a carbon capture and storage project early next year, the first of its kind in Russia. Adding in the emissions/externality costs from operating in the Arctic, it’s incumbent upon Novatek to get ahead of the curve, particularly since Gazprom has pretensions of greening its LNG supplies from Sakhalin now aided by the cap and trade program taking effect (and probably part of why Edel’geriev pushed for it there first). The hope here is that if Russia’s exporters make these changes first to please foreign consumers, they’ll begin to adjust domestically as well. From Forbes’ list of the top 50 greenest Russian companies, Mars takes first but it’s Sber in second. The race is on to realize domestic rents from making the transition by bridging that gap between foreign investor interest and, in the case of Sber for instance, becoming a go-to provider of services for greening efforts and establishing a reputation with domestic investors for innovation. The influence of foreign markets on domestic corporate behavior in Russia, at least concerning the environment, is intensifying with or without a policy program from the government and presidential administration fit for purpose.

What’s going on?

Yesterday’s attempt on the part of Roskomnadzor to “slow” Twitter on Runet proved to be simultaneously a farce and a precedent-setting cause for concern. The less direct form of censorship, mocked mercilessly on Twitter itself, came in response to the company’s failure to remove several thousand links, publications, and tweets it had been asked to remove, reportedly about calling on children to commit suicide, child pornography, and information about drug use. No one from the agency is sharing with the media just how much they “slowed” Twitter, taking an approach reminiscent to the early days of the Telegram ban in which no one offers clarifying comment on the success of what everyone saw to be a mostly fruitless effort but assures the public that they can fully block the service if they want to. Per the censor, the equipment needed to carry out the task is working fine across Russia’s regions. The possibility that Twitter bring a suit forward in Russian courts would only make sense if the company is prepared to meet all of the legal obligations put forward by the government. More important than any technical detail or the cartoonish insufficiency of Roskomnadzor’s reach the first time it tries these things is how Putin himself went on a values kick last week about the importance of moral laws being applied to the internet. The precedent is being set that these justifications will be used to harass platforms into compliance without necessarily going for a full blackout, reducing the relative political blowback from the more online part of the Russian population and still creating massive headaches for legal and other departments at firms like Twitter. It’s clearly coming during the campaign season ramp-up, and I expect more episodes like it later in the year.

The Central Bank’s bulletin for March on major trends across the economy offers a glimpse of why the current inflationary burst doesn’t seem likely to subside any time soon. It’s producers — firms consuming capital goods and providing intermediate demand for other sectors since they produce value-added things — that as driving cost increases at the moment without much help from the extractive sector. The following breaks down sectoral contributions to producer price increases:

Red = extractive industries Grey = value-added production Blue = electricity, water, utilities Black Line = Industrial PPI

Rising resource commodity costs are starting to filter back into industries while bottlenecks, over-capacity in some areas, and under-capacity in others are producing sector-specific sources of inflation while export and input prices for food keep rising. One of the biggest problems now is actually shortages of containers as consumers (and firms) in developed economies importing from China in particular have a leg up on Russian consumers/firms because of the sheer scale of consumption needs. That this dynamic is so problematic for Russia when CPI remains stuck under 2% in the US and EU really raises questions about the supply/demand balance in the Russian economy, particularly for sectors still trying to squeeze more earnings out of exports despite policy interventions and because the relative balance between services and goods spending in Russia didn’t change the same way it did in countries with harsher lockdown regimes (price deflation from a relative fall in goods demand could offset some expected services inflation). At the same time, economic activity is overshooting expectations some, which is also contributing. If the current % inflation rates remain and lacking any fiscal policy to meaningfully address imbalance, the only option will be to suck some oxygen out by raising the key rate. Until elevated prices/demand leads to high levels of investment, it’s a problem with limited room to self-correct in the short-term.

The White House’s fight to expand the state’s ability to surveil and react to economic developments has a new target: the trade in counterfeit or otherwise illegal goods. Plans for a system to monitor all of said activity are being rolled out for 2023 in hopes of offering more insight into why counterfeit/illegal production appears and to have better information to assess legal liability for said production. In theory, data on industrial production would begin to be automatically collected from the end of 2022 onwards, overcoming the limitations of the current system that’s ad hoc, lacks a unified framework or methodology, and relies on individual efforts by sectors, companies, and ministries to collect data. So why is it so important to base a ‘normative framework’ and create an industrial information system? On the one hand, it’s meant to help ascertain the size and shape of the informal economy, since its large share of GDP undermines the efficacy of a host of economic policies, particularly acute for the customs services (and FSB) which fight over rents from controlling contraband or drug flows and so on. On the other, this is also a facet of the problem of price controls. Without adequate information about illegal goods being traded, price control measures are much more difficult to maintain — and the creation of this kind of database offers another legal tool with which to coerce (or cooperate) with businesses when bargaining over prices.

MinTsifry is working out a proposal to create a legal framework allowing for the remote sale of prescription medications in hopes of further developing the services sector. MinZdrav is also onboard, but neither ministry is offering public comment at this time. Online sales of non-prescriptions medications only launched (legally) last April during the worst of the initial COVID wave and pharmacies raked in about 93.2 billion rubles ($1.26 billion) doing it. Market participants hope that establishing the framework will accelerate the development of e-services from pharmacies and the health sector. What I find interesting about these efforts from a macro/sector perspective is that they’re a vital necessity given the state of the Russian labor force. So long as the total number of workers has entered (very gradual) decline, the regime has to tenuously balance maintaining employment levels in industries that form a core for its political support via SOEs or strategic sectors, often to the detriment of their efficiency, while promoting productivity gains elsewhere. In this case, the shift towards e-commerce for medications opens up improvements for remote healthcare — all the more important for regions so long as internet access is decent — and shifting out employment in brick & mortar locations to other jobs in the economy. Since there are fewer workers each year, the fight over labor is a bit zero-sum. Any sector expanding its employment levels triggers wage increases elsewhere to retain labor, but those wage increases aren’t doing as much if inflation is higher and jobs being created are more low-wage in general. I’d expect more initiatives like this to go ahead not just for convenience and the improvement of services, but because they make it easier to manage the labor force over time (though I highly doubt that’s the dominant rationale discussed behind closed doors).

COVID Status Report

New cases came in at 9,270 with 459 deaths reported. The case load in St. Petersburg is under 6 per 1000 people and the steady decline continues, with Karelia (as always) lagging the rest. Moscow’s safely out of the top 10:

Hospitals across the regions continue to return to pre-COVID work regimes as the healthcare system normalizes with declining case loads. The Polish government is accusing Igor Oshchepkov, general consul in Poznan, of threatening the public’s health by failing to self-isolate properly after being infected with COVID-19. What’s most interesting doing some basic online searching is just how absent COVID is becoming from news reporting. The continued, if slowing, decline in cases surely is responsible for this — the regime also has no reason to shine a light on it when things are going well when it could end up being attacked for its performance politically given the low level of public trust. South Ossetia is trying to get 1,500 doses of Sputnik-V apparently. COVID has become background noise. That’s either great news for the Kremlin — things are looking up! — or a big risk if the economic recovery underperforms — not unlikely at the moment.

Matters of National Import

The government has noticed that it sorely lacks adequate means to compel Russia’s state-owned companies or else its largest companies to comply with and meet import substitution targets. MinPromTorg has been tasked with proposing amendments to the existing legal/executive framework guiding this area of industrial policy, changes to the regulation of data collection regarding import substitution, and the realization of protectionist policy initiatives. At present, the only real instrument to force companies to buy Russian is the use of state procurement requirements that can be directly tracked (but are also subject to exceptions if domestic production is sorely lacking). The main approach now discussed is setting a % or related quota requirement for procurements, a policy move first brought up as an anti-crisis measure last year. Once again, measures taken in response to the economic shock tend to stick around once it’s over, suggesting business lobbies and political interest groups around the government know that their best chance to lock in preferential treatment and state subsidy or related support is to exploit the crisis and Mishustin’s drive to improve the state’s capacity to direct import substitution efforts. The defense sector was discussing this policy approach last month with all the major ministries and relevant agencies: MinFin, MinPromTorg, MinEkonomiki, the Federal Treasury, and the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service.

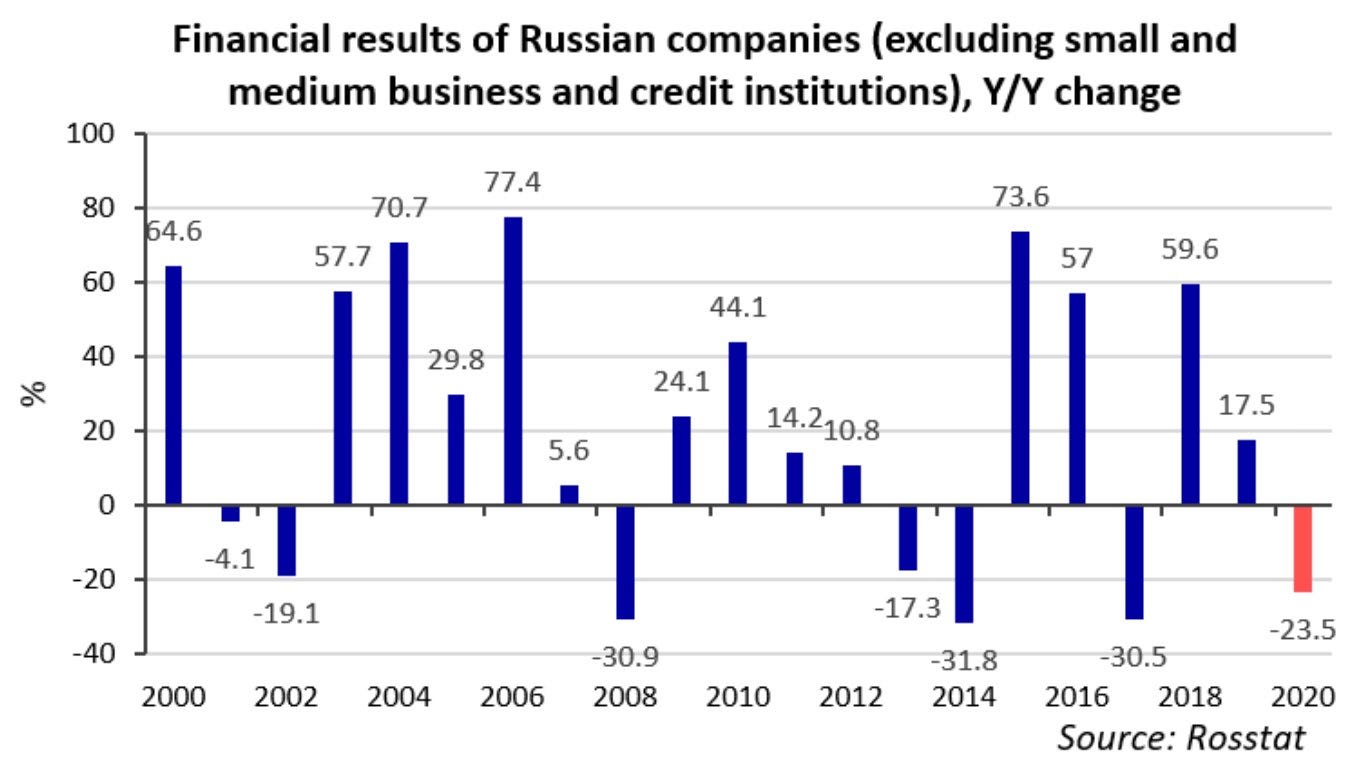

There’s precious little concrete information about what’s going on from Kommersant’s reporting aside from a continued government focus on procurements and suggestion from MinEkonomiki to offer blanket industrial production preferences to Russian industries regardless of product/good category. Many are hoping that creating some sort of universal policy mechanism not subject to countless carveouts and with sufficient oversight will allow Russia (and EAEU members) to unify their procurements markets for good. However, any such import substitution drive inevitably drives up costs, at least initially. If its easier for Russia’s SOEs to import something, it’s because there’s an insufficient comparative advantage/institutional structures/market or in-house knowledge at the firm level in Russia to recreate said import competitively. Assuming this is broadly the case, one expects production to be higher cost and therefore more expensive for domestic consumers substituting imports — admittedly subject to exchange rate fluctuations — with domestic production. To my mind, this raises long-run questions about Russian corporates, their profit margins, and the relationship between production costs and consumer prices. First, take Rosstat’s data (usual h/t to Tatiana Evdokimova) for year-on-year changes in profits — note that it doesn’t seem to be adjusted for currency valuations, so the solid performance for years like 2016 does not well reflect reality:

First off, all of the increases pre-2008 are basically just oil prices and 2007 saw an actual decline also linked to a small contraction in oil output because of the mismanagement of the oil sector tax regime. 2009-2012 is much weaker than previous years despite persistently high oil prices and 2013-2014 see net declines. 2015-2016 see increases, corresponding mostly to currency devaluation given economic contraction but some import substitution as a result as well, and then a decrease in 2017 followed by the economy leveling out in 2018 and then reflecting underlying weakness in the back end of 2019 before COVID hit. The 2020 decline isn’t really that bad all things considered. That picture starts to look a lot different when you pull the producer price inflation vs. consumer price inflation data from that Central Bank release for Jan.-Feb. using Rosstat data:

Grey = CPI Red = PPI

Producer prices have risen faster, even significantly faster, than consumer prices on the whole except for 2016 and the deflationary shock last year that cut demand vs. productive capacity. So in theory, producers are absorbing more cost increases than they’re passing on and it well could be that some of the inflation now experienced by consumers reflects the unwillingness or ability of producers to keep absorbing that difference. More importantly, if the PPI increases don’t correspond to CPI as much as you might expect — it’s not a perfectly linear relationship since PPI deflates revenues to measure real output growth whereas CPI adjusts income and expenditure levels for costs of living — and they’re rising without real growth across the broader economy, what do persistently higher levels of PPI correspond to?

My wager is that two things are going on, both of which relate to latest drive from the government to accelerate import substitution. Forgive the confusion over the underlying value for cost levels — the Rosstat data suddenly changes from 000s to millions of rubles in 2017, and the earlier years seem understated while I adjusted everything as if it were 000s. What matters here aren’t the net totals (I need to dig into the methodology to properly adjust them), but the % changes assuming some relative uniformity across the data. The ‘other’ category includes amortization, insurance payments, and the full on other category which isn’t entirely clear to me as to what it contains:

Material cost inflation has outstripped labor cost inflation since 2014, save for last year’s respite. So the lower levels of price increases passed onto consumers might also correspond to lower increases in wages relative to material costs since lower wage relative wage levels reduce the amount of end consumption for a great deal of domestic production. The lack of investment into productivity across the economy is worsened by existing labor policies that aim to sustain employment levels at the expensive of efficiency gains to avoid discontent. Import substituting production tends to be more labor intensive and costly initially until corporate competencies catch up with import competitors, which means more spending on labor and, if intermediate goods are being substituted as well, higher input costs along the supply chain. Since the industries intended to be localized/substitute imports generally receive generous protections, preferential domestic market access such as procurements, and/or subsidies, companies have little to stop them from taking an excess margin for profit above levels implied by higher material, labor, or other input costs. If they aren’t competing against imports and face limited domestic competition — the case for many SOEs — then they can extract rents by charging ‘extra’.

This obviously gets interrupted by price and production control measures aimed at better balancing supply and demand and preventing excess price increases since income levels are depressed and increases in wage levels tend to be sector specific i.e. a sector like construction might see wage levels rise more now because of shortages from a loss of migrant labor, but manufacturing wage levels might not see as much of an increase because productivity isn’t increasing as much as it could be. So a bunch of these newer programmatic measures, or proposed measures, are a play to help companies absorb higher material costs as they re-source imports to domestic manufacturers or now face rising commodity prices while they face a bevy of factors, market and politically-driven, that allow them to more easily manage wage increases. At the same time, the government is obsessed with price stability because of the political salience of price inflation. Even now at lower levels now, Levada’s polling shows Russians are most concerned socioeconomically with price stability ever since the end of the USSR:

Red = price increases Light Blue = unemployment Yellow = withheld wages/pensions etc. Black = crisis in the economy Cyan = poverty

Import substitution pushes up producer costs precisely at the same time real incomes are falling and import substitution measures risk creating ripple effects between sectors. Since many of the companies benefiting from these efforts aren’t facing significant market competition, it ends up creating inflationary pressures that have to be managed through an increasingly explicit set of arrangements. I’ve been on this theme a lot lately, but what struck me today after I spotted the initial story inspiring this column was that Putin went so far as to call 2020 the hardest year for the global economy since WWII in an obvious ploy to talk up the regime’s success. The messaging for the economy amounts to “it could have been so much worse” after Mishustin has clearly been tasked with expanding the state’s capacity to manage economic shocks and trends. Yet none of the proposals on offer help increase investment levels to break through existing bottleneck constraints or foster a competitive domestic market to avoid the rent-seeking of price inflation beyond what would occur if SOEs faced open competition from imports. I’m still trying to articulate the systemic mechanisms balancing this all together, but it’s obvious there are higher levels of sectoral coordination and state/informal influence over price formation, profit-taking, and the relationship between production and consumer costs than one might see at first glance. The worrying signs there, however, are that the system’s reaching a breaking point when it comes to its ability to produce enough rents to improve the productivity of traditionally unproductive sectors. This is Gorbachev’s dilemma all over again, but arrived at because of the instability generated by constant attempts to stabilize the economy. It can muddle on for awhile, but import substitution requires external rents and much stronger domestic demand to sustain itself so long as competition isn’t taken seriously.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).