Top of the Pops

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has been campaigning for his presumed 2024 run in the last days of the Trump presidency post-election. Pompeo’s visit to Israeli settlements on land claimed by Palestinians 5 days ago effectively put a US seal of approval on them, while also providing A and B-reel for Pompeo in 2024 to secure support with evangelical voters, hardcore conservative Jewish donors, and try to lock in the Panhandle to turnout for him in Florida should he win the nomination. Since then, he’s met with the Saudi Crown Prince, reportedly to talk about Iran and Yemen with Israeli PM Netanyahu attending. It’s a clear signal that Trump, Bibi, and MbS know it’s over in the US and now comes the hard part of making sure that the Biden administration can’t change course. Reportage seems to think it’s a tall order to do so. I think that’s a bit naive, though there are certainly harsh limits on what Trump can do.

The announcement that John Kerry was being given a role on the NSC covering climate change was a nifty bit of misdirection. For one, there’s no clear rationale for such a role on the NSC unless Biden intends to create institutional means by which such a principal could actually effect policy. More likely is that Kerry’s role will be that of a negotiator marrying national security objectives with a climate focus. The most likely reason to name him, however, is to avoid any senate confirmation and use him as an intermediary to reassure Tehran Biden is serious about re-entering the JCPOA. Kerry has some currency in Europe and among Iranian officials because of his role shepherding the talks through the first time around. I’d guess a lot of his job will be launching a reassurance tour to achieve consensus again under cover of his new policy portfolio. But he and Biden have a serious problem there: Trump’s presidency has increased congressional scrutiny over foreign policy decision-making, particularly when it comes to sanctions or other long-term, quasi-contractual aspects of statecraft. The democratic leadership in congress don’t like the JCPOA and will demand more. Senators like Chris Coons represent the default position that any return to the deal should entail "squeezing more” out of Iran.

It’s hard to imagine any agreement occurs if that’s a base negotiating point, and Biden would be wasting a large amount of political capital he needs to deal with stimulus talks and economic matters — no, Yellen is not a bad pick for Treasury but she isn’t going to go far enough either — if he picked a fight with his own caucus over this. He ran ahead of the party down ballot, which is his only insulation on the matter. Pompeo and crew are making it as hard as they can to unwind what’s been done and policy bandwidth is going to be the biggest problem, assuming Biden’s serious about Iran and not just placating his party. Sullivan, his NSA, was key to negotiating the deal too. But people forget that he helped push the most incoherent and short-sighted aspects of US policy in Syria and Libya, thanks to him being team Clinton even when he was working as Biden’s NSA for 2013-2014, and Syria is going to become part of any talks. Biden is now in an electoral trap, and that’s precisely where Pompeo and Trump want him. 2021 is going to be a mess.

Around the Horn

On November 20, Belarusian president Aleksandr Lukashenka announced that Russia had postponed debt service repayments owed for $1 billion worth of debt. This follows up on a mid-September promise to extend Belarus $1.5 billion. As of October 1, Belarus’ state debt had grown 32.1% — the increase has largely been external debt rather than anything financed domestically. Minsk, however, has struggled to get any money out of Beijing — an increasingly important financial partner who has targeted investments into the country to support the expansion of trans-Eurasian rail freight routes. Train cargo transiting Russia between the EU and China basically has to funnel through Belarus into Poland, but doesn’t produce rents on the scale needed to replace oil & gas export earnings. Belarus’ economic model has been exhausted for years now, that’s not news. But lacking a growing financial market and facing economic stagnation, Belarus is faced with an old, Soviet-style challenge: export earnings have to cover debt service costs and ease the strain of importing goods. The country normally runs a small current account deficit to boot. The only potential good news would be European refinery closures which, in some instances, would slightly improve the marginal return for re-exports of Russian crude that’s been processed at Belarusian refineries.

Ukraine’s industrial output was down about 5% year-on-year as of October while Zelenskiy and the Rada stumble for policy prescriptions. The most recent presidential order withdrawing Ukraine from a CIS agreement on monopoly policies is officially aimed at cutting off the legal rationale for the transfer of economic information that could be used by non-Russian CIS states to pressure Ukraine in trade and business talks. Seems much likelier that it’s a populist stunt with limited effect, particularly since economic shocks are the worst time to increase trade friction. Ukraine benefits from a diversified portfolio of export partners. I pulled 2019 export data since that generates currency earnings and external demand matters for maintaining domestic demand for imports with the country’s current account deficit of around $10 billion:

The EU accounts for about 40% of the country’s exports, and that means that potential deflationary contagion from the Eurozone into non-Euro members of the EU is a big risk. Poland’s done a particularly good job warding off deflation thus far. But the shift of Western European industrial supply chains into Central and Eastern Europe means that transmission of deflationary shocks from a failure to generate enough demand in the Eurozone's core economies as well as finalize a recovery fund approach (blocked by Hungary and Poland) are going to hit Ukraine, especially with continued problems in Turkey, persistent contraction and stagnation in Russia, and China’s supply-side first recovery. Fiscal constraints due to reliance on external debts to finance deficits prevent larger stimulus plans, but Ukraine’s managed to get inflation to around 4.5%. Considering the size of the shadow economy and some similarities with the Russian economy, that’s de facto stagnation. Kyiv needs the current bull run on global equities generated by Biden’s win to turn into concrete stimulus plans, especially given the clear backwards turn taken in dealing with the power of figures like Kolomoisky and keeping the IMF happy.

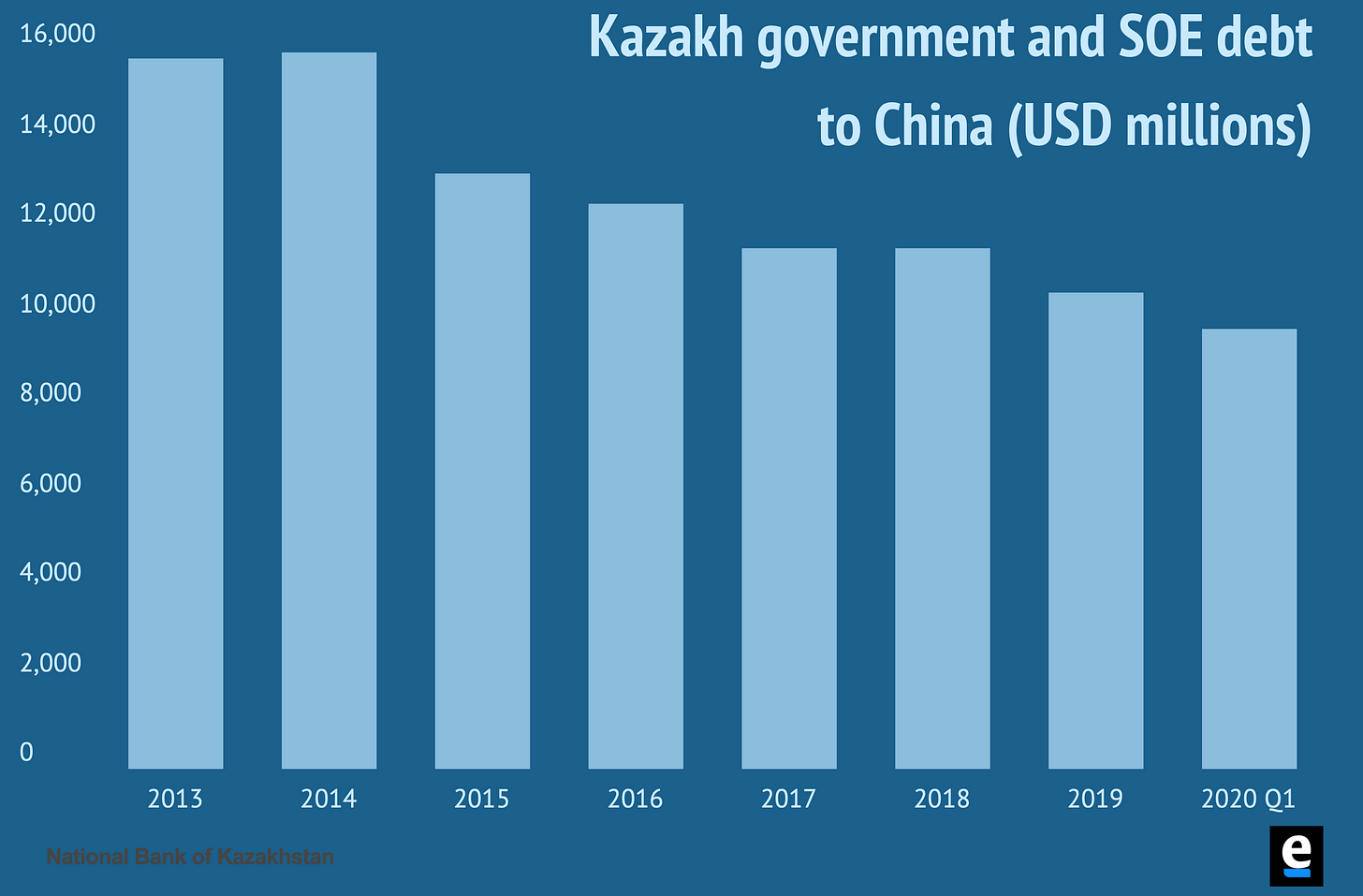

Kazakhstan’s weathering the storm better than most across Eurasia, currently holding its GDP down just 2.9% year-on-year. With oil climbing past $45 a barrel now that Trump has effectively conceded without conceding, external trade earnings and budget strains have to be easing slightly at the moment — policy planning earlier this year cut the budget’s oil price expectations and banked on oil settling in the $35-40 a barrel range. What’s interesting to me, however, is that the current oil shock has depressed investment into the sector which, by default, increases the relative rates of investment into services and non-oil & gas industries in Kazakhstan. In 2014-2015, the primary stimulus focus was to target infrastructure development and freight transit from China as well as try to attract some parts of supply chains into and out of China. Further, China’s been changing its investment footprint and reducing its exposure to infrastructure while Kazakhstan is paying down debts to China and currying investment into newer sectors.

China’s supply side stimulus will limit space for some industrial investments, but it’ll want to find new areas to profit. Weak external growth means that current estimates of export losses worth $660 million annually due to barriers within the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) become more salient for business lobbies. That’s just .4% of Kazakhstan’s 2019 nominal GDP, so let’s not pretend it’s a game changer. Demand in the EU and China matter way more for Kazakhstan’s business cycle and prospects. But the Ministry of Agriculture is currently trying to conclude agreements with other member states to expand market access for Kazakh agricultural producers. The external economic environment makes deeper trade integration more attractive in a world of lower growth and a means. of attracting more diversified Chinese investment, and with that offers from European and Russian firms trying not to lose out. Watch that space.

Sorely winning

Things still aren’t settled in Nagorno-Karabakh and it’s becoming clearer that while Russia threw its muscle into the fray to settle things, it hasn’t emerged as confidently in control of the situation as it probably would like. Russia’s now disputing a proposal from Ankara to establish an independent military outpost in Azeri territory, the type of move I expected would pose problems since Russia can’t effectively veto how Baku handles its own sovereign territory without a big stick. 2 days ago, Turkish mouthpiece outlets were lining up sending troops per the original agreement to have a joint monitoring center with Russia. Once you’ve got commanders and soldiers on the ground, well, they can raise a ruckus and play games with the 2,000 strong deployment Russia’s now put into the field. There are already reports of Armenians, now effectively forced to leave their homes due to the territorial exchanges, setting fire to them as they go. Russia has experience with peacekeeping deployments, but that doesn’t ease the complexity of keeping soldiers with strict limits on their rules of engagement in an area filled with people at turns triumphant and furious and third-parties with a clashing view of what’s right. A Russian officer just ended up in the hospital in Baku from an injury sustained from a landmine explosion. The juggling act only gets more complicated the more Turkey tries to entrench itself diplomatically.

The links between Azerbaijan and Turkey are here to stay. There’ll be plenty of small-scale business accords, financial agreements, trade chatter, and more to come. The biggest problem with Baku’s gamble is now it has very little room to maneuver between the external powers bordering the South Caucasus. Eyes now on the lobbying front. Turkey, for example, lost its business with Greenberg Traurig in Washington due to pressure from Armenian-American activists, but that’s pretty irrelevant. All the pressure in the world did little to force firms to drop the Saudis after Khashoggi’s murder because, especially in times like this, people stop paying attention. Biden’s incoming team are going to face a lot of congressional pressure to punish Turkey, but it’s frankly unlikely to get very far given the continued room for US and Turkish interests to align. Azerbaijan is now locked into winning the right hearts and minds in foreign capitals and waiting patiently for opportunities to prod Moscow’s agreement.

One might rightfully view the way the conflict ended as a ‘victory for realism,’ whereby hard power and the ability to leverage it determined the outcome in the face of international norms and “rules” governing state behavior. But to claim such a victory as a ‘win’ for Russia ignores the fundamental assumptions made by a realist framework for the conflict. Power is always unstable, imbalanced, and the object of state actions. The current peace enforced by Russian peacekeepers is certainly unstable and imbalanced, and will only become more so given that Ankara and Baku have little reason not to keep pushing for more and Armenians in Stepanakert seem to doubt that peace will last.

Azerbaijan’s now beginning the long process of rebuilding, with estimates saying it’ll take 10 years and about $15 billion to get the territories gained in Nagorno-Karabakh back on their feet. $15 billion may be in the range of a quarter of Azerbaijan’s GDP, but it’s actually not that burdensome a sum. The key rate now stands at 6.5% in Azerbaijan, a fair bit higher than in Russia since oil & gas exports and revenues account for a much larger share of fiscal revenues and national GDP. Theoretically, SOFAZ has the cash-in-hand to cover that, though it’d trigger insane inflation, but they can use it to buy fixed-income assets or make business investments that would be used to service debt payments from either sovereign issuances or else money borrowed externally or from domestic banks. The more Azerbaijan invests and builds, the greater the pressure on the Armenian side to act before it’s too late. Or else facts can change on the ground.

Newly-elected president Maia Sandu in Moldova is calling on Russia to remove its peacekeepers from Transnistria in an attempt to advance diplomatic efforts to find some means of resolving the conflict. It’s worth considering that these calls aren’t new, and aren’t going to come to fruition (yet), but they symbolize how a peacekeeping operation can harden political lines against Russia. The trouble with Russian influence via peacekeeping is that it’s most useful as a pressure point when Moscow can reasonably influence political actors on the ground to take stances that benefit it. While Russia can pressure Armenian elites to deepen cooperation, the public is furious at them. And Russia has precious little influence over Azeri policy since Aliyev controls all the relevant levers of power and has cultivated strong enough ties with other actors, including some in the US and EU, to provide him cover. This has “winning loss” written all over it.

Auto-da-flation

European deflation is going to, differentially of course, hit Eurasia’s commodity exporters pretty hard given that they’re largely stuck between Chinese and EU demand. The latest on Euro long positions sends a bad signal:

The market, save hedge funds, is going long on the Euro, which by default means they expect deflation. This creates a short, medium, and long-run dilemma, especially for funds like SOFAZ managing currency reserves in order to maintain macroeconomic health. The Euro is an attractive store of value because of deflationary pressures — it’s also going to net any exporters paid in Euro contracts a little extra cash initially — when compared to the US dollar. That makes it worthwhile to stockpile more as reserves to ensure currency strength (or at least ward off further devaluation) for exporters dependent on foreign-denominated earnings. But the more they stockpile, the more demand for the Euro reinforces market perceptions for long-Euro positions, and the greater the drag on European exports and, by extension, inflationary pressures within the Eurozone. It’s been put on the back burner, but the European Commission would most certainly like to see an increased role for the Euro on global commodity markets.

This a grossly over-simplified snapshot — much of this trade is within Central Asia, much includes Russia, and it was just much faster to pull than currency data — but this gives you an idea of why currency politics around the Euro really matter coming out of the current crisis across Eurasia:

Euro liquidity will have to keep pace with demand for the currency, but as it stands, the Federal Reserve is out-easing the field. The result of that is a decline in the relative value of the US dollar, but complete confidence in the availability of or access to dollars when needed. Eurozone and EU deflationary pressures are going to feedback into central bank policies in the South Caucasus and Central Asia as weakening demand for commodity exports will pressure current accounts if they can’t successfully place export volumes onto the Chinese market or elsewhere. Worse, a stronger Euro means that eurobonds and euro-denominated debt/loans are riskier, which will trigger some to shift back towards dollars if they aren’t comfortable using ruble-denominated instruments depending on where the ruble ends up in 2021 and different rates of economic recovery (though obviously the region correlates to Russia most of the time). Russia has far more fiscal capacity to adjust because it has a larger economy, more things it can tax, and a lot more people. Other regional economies won’t be able to rely on the same kind of credit expansion given the relationship between current accounts and bank sector liquidity for many (not all) Eurasian economies.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).