A Short Note

A quick note: Wednesday I’ll be putting out a shorter, second newsletter response to the latest on Biden's transition into power — and the Democrats’ usual foibles. And while today’s about Eurasia, it’s difficult to not touch on the Navalny protest activity over the weekend. So this became more of a ‘think piece’ than straight analysis, but there’s some after the initial column geared towards that.

Quick Hits

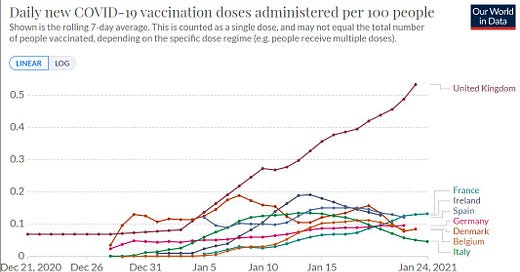

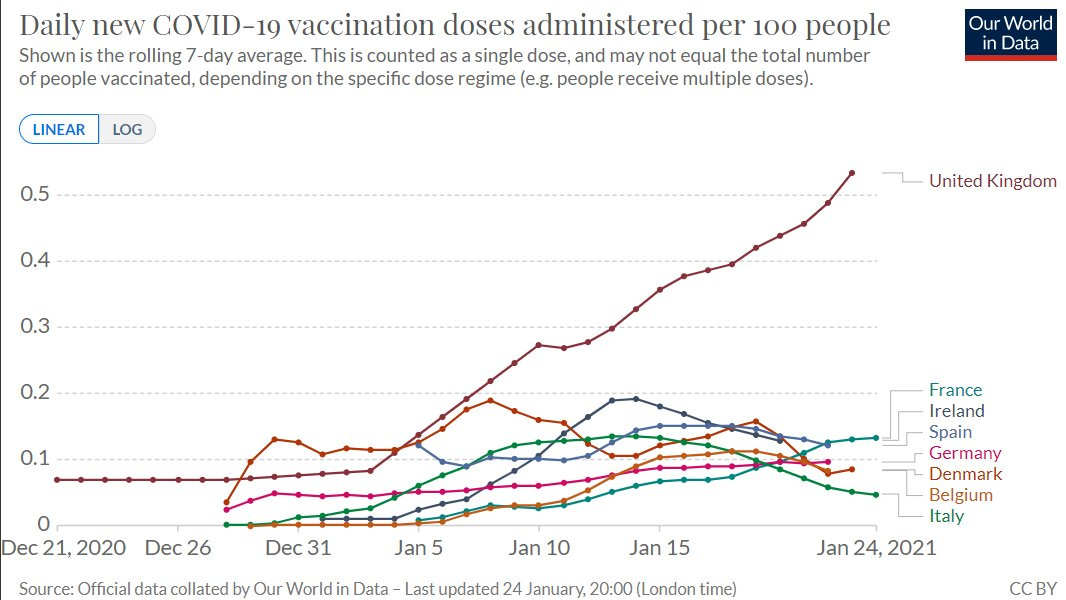

21 MEPs from Eastern European EU member states are calling on the EU to step up its efforts in vaccine diplomacy to make sure that Eastern Partners — and presumably Central Asia — get access to vaccines to avoid Russia and China currying favor through diplomatic initiatives. There’s just one problem:

Brexit may mean Brexit, but the UK’s making the EU look like fools when it comes to distribution and vaccination. Not only will that weigh on recovery, but it also reflects the fact that the EU — even with its investments across the Caucasus and Central Asia — is a bit player when it comes regional politicking outside of specific connectivity and infrastructure programs. It’s evident from comms elsewhere no one in European capitals is prioritizing others at the moment.

Ukrainian foreign minister Dmitry Kuleba went on air on ‘Ukraina 24’ and sold the line that Ukraine ought to detach itself from the connected energy system of Belarus and Russia and hook itself up to that of the European Union by 2023. It’s a bold statement given that Zelenskiy has had to negotiate hard with the IMF over price caps on natural gas cost increases for end users, a huge trigger point for inflation in the dead of winter, especially among pensioners and those living on fixed-incomes from social transfers. If that’s the end game, then Kyiv is probably trying to make a bargain — greater freedom to regulate prices in the shorter-run while agreeing to broader energy price increases in support of a more aggressive energy transition agenda than would be feasible while using the Union State’s grid.

Last week, Moldovagaz was forced to pay Gazprom $246.6 million for gas imported in 2017 by an international arbitrage court. There may not be many cases like it in the future. Moldova finally finished its interconnected to the Romanian market last year and is now expected to transit as much as 3 bcm of gas via the Trans-Balkan pipeline in 2021 making up for lost transit fees collected from Gazprom before the completion of TurkStream. Market reforms to increase the competitiveness of the pricing structure in Moldova are likely to follow to improve the country’s legal interconnectedness with the regional market and EU regulatory infrastructure now that the physical pipeline has been built. Still, transmission tariffs are currently 3 times higher for transit volumes than those for the local operator due to fiscal pressures. That may have to change if Chisinau wants to reduce Gazprom’s leverage over flows.

Last week, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan signed an initial agreement to jointly developed the Dostlug/k field in the Caspian. It’s a small find, but the hope for some is that it paves the way for Turkmen pipeline exports to Europe via infrastructure in the Southern Gas Corridor. That still seems a stretch for the simple reason that it’s not clear demand will merit another pipeline project. The current prospects for Europe’s economy recovery are grim:

Great slack means more labor/capital resources going unused. The European Commission figures are way worse than the IMF figures, and a lot of this has to do with how COVID support schema have maintained employment levels using furloughs and short-time work, hiding the extent of economic scarring taking place. Ashgabat shouldn’t get too excited. If it gets a pipeline, it’ll be a payoff to ensure the country doesn’t collapse, not a result of strong natural gas demand in the coming years.

Things Fall Apart

Roughly 3,400 people were arrested nationally as protests happened across a huge swathe of the country with Navalny’s team estimating that somewhere between 250-300,000 people protested in total. The initial data collected shows that it’s 25-35 year olds really driving this surge of activity, which both makes sense and is a huge problem for the regime. It’s precisely that cohort who’s seen greater employment losses, fewer benefits from the stagnation for macroeconomic stability bargain across the economy, have seen their relative ability to accumulate savings decline in greater terms than those older than them, and more. Too much is made of ‘mirroring’ between regimes in Eurasia i.e. a political crisis in Russia doesn’t necessarily contain immediate comparisons with neighboring states, but the demographic profile of these protests and the underlying economic drivers amplifying the political salience of Navalny’s attack on corruption are reflective of regional problems, not just Russian ones. Whatever comes next is surely being watched closely in Eurasian capitals, even if its dynamics are largely idiosyncratic to Russia.

It’s interesting to consider as well how protest activity has varied or been channeled. Whereas economic stagnation has dovetailed with the over-centralization of political power in Belarus and Russia — and while early, many see parallels with the new Navalny protests and Belarus — Kyrgyzstan’s protests reflected a far more pluralistic political environment amid shared economic struggles, protest potential in Azerbaijan was channeled into the war effort with Armenia, and the post-war protests in Armenia are now being channeled into an ongoing fight with Pashinyan over holding new parliamentary elections (instead of his resigning) that may produce some interesting result. The picture varies more broadly, but we can clearly see a mix of economic policy failures and pluralistic (or not) political systems still navigating the impacts of COVID on livelihoods, expectations, and the state’s capacity to act, and then inflected by the politics around existing conflicts — Transnistria, South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Donbass and Crimea, and Nagorno-Karabakh/Artsakh. Ukraine has seen protests over rising costs for housing and basic utility services (namely gas for heating), Moldova’s now hosting dueling pro and anti-Navalny protests, protests in Georgia against rigged parliamentary elections early last November didn’t give way to anything sustained since (but also reflect greater political pluralism), protests in Uzbekistan now concern shortages of gas and electricity, protestors in Tajikistan are also fighting against limits on their electricity use, and last year Turkmenistan saw the largest scale protests since 1991.

Polling and eyewitness accounts may offer various reasons for protests to be taking place and offer much greater nuance as to how they developed across the region broadly. Some of this is also undoubtedly COVID-related. But the shock to energy markets and demand this last year is a Eurasian crisis. Every prior commodity shock, whether generated by the global financial crisis or the after-effects of the GFC, the rise of US shale output, and global slowdown in emerging market growth, has a lead to a steadily diminishing growth rate for the region’s economies. Commodity exports drive balances of payments, bank sector liquidity, credit expansions, wage growth, investment cycles, the rhythm of how most Eurasian economies have fared since independence. Georgia relies on tourism flows, Moldova on Russia and its relationship with Romania and the EU, others on remittances — all rely in their own way, though, on external demand even if the current account doesn’t always show it. Russia’s refusal to be an economically responsible steward domestically and in its ‘near abroad’ worsens political instability across Eurasia, and ends up encouraging the use of repression to ensure calm as publics face structurally diminishing material prospects — this dynamic doesn’t capture Uzbekistan as well, but the current crisis has taken much of the wind out of the success of post-Karimov economic reforms.

Not enough attention is being paid to how models of economic growth in Russia, China, and the Eurozone are likely to shape most of the options these countries have in the years to come. Economic stability is core to the issue of any future democratization for the simple reason that elections concern the distribution of rents. Corruption has proven a useful wedge issue in Russia because it reveals the extent to which rents are being extracted and dealt to elites instead of the nation. That doesn’t mean it acquires the same salience across Eurasia, but elites understand that if incomes aren’t rising, it’s harder to get people to look the other way. That necessitates new forms of mobilization politics — Japarov could herald similar shifts elsewhere, though it’s important not to over-read similarities across countries. That chart is just World Bank data, and it also doesn’t capture the whole picture because it doesn’t factor in relative levels of inflation, which are transmitted differently in different economies. But over the last 20 years, the relative level of growth has diminished when measured not just in terms of raw outputs — resource exports drastically skew the amount of actual value being created and distributed at the national level — but in terms of prospects for wage growth and rising standards of living. Metals & minerals will offset some of the losses, but they simply don’t lend themselves to rent distribution in the same way oil & gas do. Eurasian economies need to lock in demand for non-resource exports. Unfortunately, Russia — and potentially some European economies linked via transport corridors — appear to be the only options.

Trading on Reputation

According to Russian deputy minister Aleksei Overchuk, Russia’s hopeful that Uzbekistan will progress from being an observer state within the Eurasian Economic Union to a full member. After early gains harmonizing external tariff levels with the bloc, it appears that Tashkent is now looking to harmonize its tax system with that of Russia. I’ve long thought that Uzbekistan’s initial moves to align its trade policies presaged a path to succession, and if Uzbekistan were to join, it would greatly help the integration of trade in Central Asia by providing a newer, heftier counterweight to the constant fighting between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan over the illegal re-export of goods imported from China, random phytosanitary controls, and other interruptions frequently linked to business lobbies and political figures connected to the customs services’ that can turn a profit off of short-term disruptions. Just as crucially, it’s a large market. Not only is Uzbekistan Central Asia’s most populous country, but it’s growing fast — the population increased by 6.4 million between 2010 and 2020. That’s 23% growth. It’s expected to hit 37 million by 2030 per UNICEF.

Russia is desperate to incorporate Uzbekistan because it will become the largest non-Russia market in the EAEU in terms of sheer number of consumers and, crucially, can usefully align the legal and regulatory frameworks for labor migration. The two governments signed an agreement at the end of 2020 simplifying the entry process for Uzbek laborers coming to Russia and a combination of COVID-related business losses, shifts in labor expectations, and Russia’s structurally lower birth rates create significant pressures to maintain employment levels, especially for growing industries like the agricultural sector. Mirziyoyev’s government has set a target of $12 billion for goods and services exports in 2021, and they know full well that value-added production is the best way to take advantage of the country’s relative wealth of labor compared to its regional peers. Only full membership in the EAEU can set the county on a path to make use of Russia’s half-liberalized state procurement scheme granting access to EAEU exporters as well as eliminate tariff and some non-tariff barriers to a market where there’s political will to try and relocate whatever trade feasibly can onto EAEU territory.

The EAEU matters all the more because of what’s going on with China. Take China’s trade with Central Asia and the Caucasus:

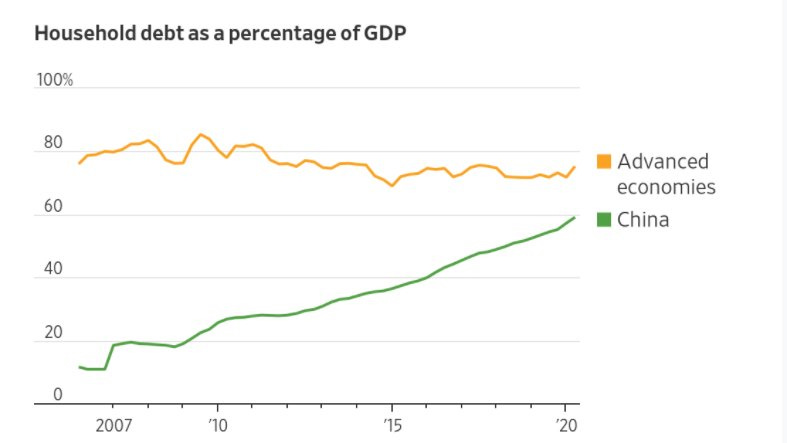

China’s export surplus surged while its relative level of regional imports fell. Uzbekistan — and the rest — are basically counting on China to do the heavy-lifting for commodity demand to help their economies, but the hope has long been to expand their own part of the value-added supply chain to be able to import value-added production into China. That requires China continue its rebalancing shift from an export-led economy to a consumer-led one. There’s just one problem:

China’s begging to approach the same levels of household indebtedness you’d see in the OECD, which naturally puts a break on growth as private debt climbs. There’s a reason to expect a slowdown in China this year as the government allows more corporate defaults to take place and tries to reduce the overall strain on the financial system by allowing some companies to fail, a gamble since any large decline in real estate prices could drag down economic growth significantly. All this means that the consumer economy in China will still be there and strong, but it’s not going to provide the same growth impetus for countries like Uzbekistan it could have a decade ago had trade been opened more then. Russian consumers struggling to find replacements for imports from the West they can’t afford to pay anymore would benefit from manufactured goods coming in from a lower labor cost economy like Uzbekistan. Russia has few other options thanks to its sanctions stand off with Europe.

Tashkent can open a large window for itself by joining, especially if it maintains more foreign policy independence on matters like Afghanistan where it’s been working closely with Washington to the extent it can since 2017. COVID’s part of the game too, Over 9,000 Uzbek citizens have taken part in trials for China’s COVID vaccine, which can’t have gone down great in Moscow save for the fact that they aren’t even vaccinating Russian citizens anywhere near the rate they’re claiming. Gas exports fell nearly five-fold against 2019 levels last year. Reality is that export earnings from energy are unlikely to recover even with better prices as Gazprom’s export capacity to the Chinese market expands and investments into further upstream capacity will be largely focused on meeting rising domestic demand given the country’s rapidly-growing population. The EAEU will be an important bargaining chip for trade. And the more that Central Asian economies use it to set norms and rules, the more it can be used to negotiate with China over what will be a changing trade balance in the years to come. Without a coordinated industrial policy, it’s hard to see how Central Asia recovers from COVID.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).