Emission Impossible

MinEkonomiki talks greenhouse gas emission reductions, but it's not for real

Top of the Pops

Tatiana Stanovaya’s diagnosis of Alexei Navalny’s arrest is straightforward: the regime is thinking in terms of security with the mindset of siloviki and domestic policy personnel and agendas now serve the siloviki. That’s why they’re acting with such lawless impunity and not sweating the risk of protests across the country. To my mind, that’s quite an unsatisfying explanation, as much as I do think it tells an important part of the story. Navalny’s direct appeal in court, pointing out the complete lawlessness of the criminal proceedings against him now underway, is something to see:

"I have seen plenty of mockery of our justice system, but this old guy in the bunker is so afraid of everything that they just defiantly tore up and threw the Russian Criminal Code in the trash. It is unbelievable, what is happening here. This is simply the ultimate lawlessness."

It’s slightly lazy analysis to say this is the complete takeover of the siloviki. Every aspect of Russian life has been steadily securitized over the last decade, and it’s not just the siloviki who are responsible. What seems likelier to me as a more holistic explanation is that the authorities now have a problem: they want to centralize power in the Duma in United Russia’s hands in order to prevent the systemic opposition parties from having any space to align with non-systemic opposition political figures on an ad hoc basis to advance their mutual interests and they know that the public does not trust United Russia or the government, no matter how positive the state-funded figures for Putin and Mishustin look from polling. No matter how unpopular Navalny may actually be when you dig into the polling — 49% of the country doesn’t even believe he was necessarily poisoned at all or else by the FSB — he possesses a national platform and the ability to make the various, frequently farcical attempts to restore some semblance of political legitimacy to United Russia exceedingly difficult.

I completely agree with Stanovaya’s basic point: the security wing of the political establishment is pushing a broader crackdown against free speech, political opposition of all kinds, and trying to expand the state’s control over the economy and social life. But now is the perfect time to arrest Navalny. Winter weather hinders a lot of protest activity and by the time the Duma campaign season rolls around, the regime can talk up its success rolling out the vaccine and win back public support by fully reopening the economy (assuming mass vaccinations go well enough). It’s a gamble, and a big one. But I do think the regime cares about the optics, they just prefer to see protests and public discontent when it can be managed (partially, if not completely).

What’s going on?

In an interesting development, MinPromTorg has worked up new regulatory guidelines allowing producers from other Eurasian Economic Union members states to take part in state procurement orders. The new approach is aimed at mollifying Belarus and Kazakhstan, both of whom wanted to improve their current account balances and export earnings by exporting to fulfill Russian state orders given that Russia accounts for just a bit over 83% of all procurements in the EAEU. The shift was possible primarily because of the attempts to harmonize rules of origin standards, an issue area that became all the more salient when state procurements were needed to meet public health needs in response to COVID-19. The move isn’t a sea change for the EAEU, but it does show that it does serve a positive trade purpose as I’ve argued occasionally in the past. Rather than conceiving it as a failure, it’s become a means of creating a (relatively) insulated economic zone that Russia now may be interested in using more to make up for domestic failures of import substitution. It’s too early to tell conclusively, but if that’s the direction of travel, Kazakhstan is the biggest beneficiary as western firms would love to compete using JVs and other structures for Russian contracts and, eventually, the Russian market if the import substitution agendas evolves as a result of the need to shift trade protections in response to COVID.

Data from the presidential administration’s research arm shows that real wages rose a bit starting in November after getting crushed for 7 months. The wage decline in year-on-year terms had closed to a lowly 2.3% by mid-December from its 9-11% trough. There’s just one problem, though — private sector wages are screwed as ever:

Orange = state (budget) sector Gold = real wages Black = private sector Green = nominal wages

What we’re seeing is the expected bifurcation in the data between those getting paid out of the budget who’ve seen their annual raises extended and are set to see their wages rise slightly due to staff cuts and the rest. Mishustin has already authorized the closure of 32,000 positions and set a new 30% staffing limit on various administrative support functions that bloat most ministries and agencies with the aim of reducing federal job openings by 5% in total and regional/territorial job openings by 10%. Thus fiscal and macroeconomic conservatism that damages the private sector recovery ends up benefiting civil servants and, crucially, makes government work that much more attractive the longer private sector wages stay lower during the recovery, which in some instances will undoubtedly affect the talent pipeline available. The problem is self-evident. Weaker consumer demand feeds back into weaker private sector wages, and weaker private sector wages feed back into weaker consumer demand. This is evidence of the failure of Russia’s stimulus policy given no further big spending initiatives are in the pipeline. Vaccines don’t put money in people’s pockets alone.

MinFin’s worst expectations about collapses in regional budget finances never came to pass, as the net decline in regional government revenues in 2020 was roughly a quarter of what was forecast: 220 billion rubles ($2.96 billion) vs. an expected 850 billon rubles ($11.44 billion). As a result, regional government spending was actually 15% higher than in 2019. There’s a massive catch, though. The increase was largely accounted for by an increase in investment projects and capital investments. In other words, regional budgets were used to prop up investment projects paying out politically-connected contractors with the intention of maintaining employment levels rather than providing benefits, income support, and other related social spending measures. What’s basically happened is that every region that can finance extractive industries has support and is scrambling since those industries generate export earnings and higher tax receipts than consumer goods and services for the regional government. That’s not the whole story, but I’m willing to bet that the new round of fiscal consolidation and supply-side stimulus response will only end up strengthening the fiscal role of resource extraction, and by extension further distort the allocation of capital away from growing consumer sectors that would make the import substitution campaign more efficient.

Maxim Tysgankov writes a great think-piece column for VTimes that points out an obvious problem I never thought to interrogate before: the Russian government has no unified definition of poverty in its policies and has no formal programmatic approach to raising incomes to reduce poverty. The Audit Chamber along with the Center of Long-term Administrative Decision(making) note that there are a 1,000 federal programs and initiatives that could be directed at poverty reduction, 60% of which might actually work to help. One of the problems right now is that as the state launches more and more electronic service portals and seeks to minimize citizens’ interactions with actual bureaucrats, Russians who lack internet access can’t actually access the services to which they’re potentially entitled. This gap is an effective form of austerity politics for Moscow. Underinvest in the country for the sake of its macroeconomic stability and cut off more potential budget costs while undergoing yet more fiscal consolidation. 20% of those in need received no financial social support to which they were entitled from 2014-2018. That’s a huge drag on the low end of the economic spectrum where the propensity to spend (and support domestic demand) is highest. As Tsygankov points out, the lack of clear indicators or measurements of poverty reduction make it impossible to formulate successful policies. I’d argue they want it that way, but that’s for another day. It’s an important question to ponder — to what extent do failures of state administrative capacity and responses to poverty weigh on growth and well-being? The answer to both is a lot.

COVID Status Report

Infections fell below 23,000 while deaths dropped to 471. It’s not enough to mark a new downward trend, but as usual, it’s large variance in Moscow driving the overall figures. The regional distribution of hotspots is unchanged:

Bashkiria is reportedly introducing COVID passports for those who’ve been vaccinated or else have COVID antibodies after beating the infection. Soldiers stationed in Siberia are starting to get their second Sputnik-V shots so you know the nation is resting easy with its armed forces at a high level of readiness. The interestin action, however, is in the Duma. Sergei Natarov of the tenuously named Liberal Democrats has called for a moratorium on exports of Russian vaccines until the mass vaccination program makes adequate progress. It’s an interesting pressure point between foreign policy prerogatives — the Kremlin clearly wants to close as many vaccine agreements abroad as possible to spite the West and offer a cheaper alternative — and the domestic policy approach to COVID relying almost totally on mass vaccination given the refusal to adopt renewed protective measures and social support spending. Though the picture is unclear, one thing is certain: regional governments are at least communicating that they’re swiftly increasing vaccination targets and vaccination site capacity.

Gas you like it

Everyone knows that Russia’s Paris Agreement is a sham. Putin signed up because Russia would already qualify as having met its commitments to reduce emissions since its reference target was the Soviet Union, a country that included the emissions counts from a further 14 countries now in existence and one that less efficiently used natural gas as a power source. But now it appears that MinEkonomiki is getting serious about climate change targets, laying out new aims to improve energy efficiency by 30% by 2030, further the modernization of the national power grid, attract more non-budget financing, extend more subsidized loans for needed investments, certify businesses’ energy efficiency gains to offer incentives, set emissions-related targets for state procurements, and more. The end result would entail a 48% decrease in greenhouse gas emissions. That’s far more ambitious than anything Russia’s economic policy institutions have ever laid out in theory. In practice, it’s not that big a change. Still, it’s a significant marker of the direction of travel in Russia on climate issues.

On the one hand, climate change risks are a serious problem for Russia despite whatever gushing nonsense the New York Times puts out about Russia “winning” from the climate crisis. Climate change negatively affects the country’s existing breadbasket in its Southern European regions and while it may extend the growing season and improve crop viability elsewhere, infrastructure outside of European Russia is terrible, costs of living are often worse in remote regions than wage adjustments can account for, and the regions most viable are the least populated and no one wants to move there. Yes, Russian agriculture may benefit, but it’s entirely unclear whether or not human preferences and the country’s under-invested infrastructure can keep pace.

On the other hand, this is clearly about economic competitiveness and security. If Russia doesn’t move quickly to improve the energy inefficiency of its production and power-generation complex, it’s going to be unable to export value-added production competitively to Europe, the US, and many Asia-Pacific markets as carbon adjustment mechanisms become normalized in the next decade. Furthermore, energy inefficiency is costing the budget by increasing subsidy requirements for consumers and industries to prevent energy costs from leading to unemployment and yet further losses of real earnings and spending power. There’s one massive problem with all this. Russia’s in desperate need of an investment breakthrough in terms of the levels of investment taking place in the economy relative to GDP. From Rosstat:

This understates the problem since the national figure is not weighted for regional GDP and regions that are more remote like the Far East frequently have a higher share of investment to GDP, not because of any success, but because of the low level of output and effect that state-directed or subsidized industrial investments have on the figures. As you can see, net investment has been declining since 2012-2013 when oil prices were around $110 a barrel and hasn’t recovered since. The 2019 data might show a slight increase, but 2020 will undoubtedly show a drop, though one mediated by the state’s preference to prioritize sustaining investment during the worst of the pandemic over consumer demand. Changing and improving energy systems is very expensive, a problem now hitting electricity providers in developed economies who’ve seen their profit margins squeezed by policy preferences for sales of volumes of electricity generated by green power, the increasing flexibility of supply in meeting demand fluctuations due to regulatory changes as well as the diversification of energy sources, and more. Much of that doesn’t exist in Russia, and firms still get squeezed because of price control measures.

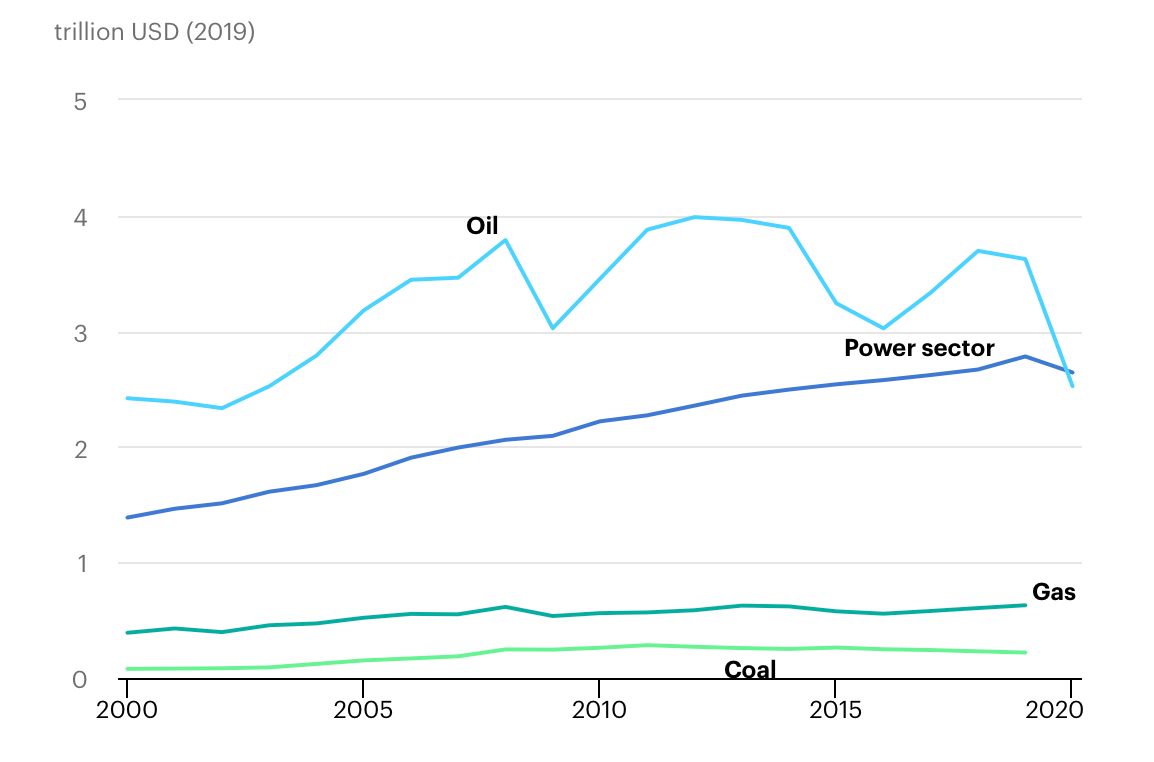

COVID has hit energy investment, but not investments into power generation as much as you might expect:

After all, we’re consuming as much, if not more power in some cases staying at home during lockdowns. The mileage my XboxOne has a gotten during my continued under-employment attests to that. More importantly, the shifting capital investments into green energy tend to reduce the equity value of investments into oil, gas, and coal. That’s a huge problem for Russia since oil, gas, and coal provide so much in the way of employment, tax, and export earnings. Emissions reduction targets, however, don’t necessarily entail using green energy since MinEkonomiki’s language pretty clearly is aimed at energy efficiency gains with existing power systems and sources. Energy intensity is therefore the main aim, and it currently stands about 9.62 tons of fuel equivalent per 1 million rubles of GDP as of 2019 with the expectation that this will fall by more than a third by 2030. In other words, the existing policy course would improve energy intensity by over 33% and do all the lifting for emissions reduction.

MinEkonomiki found a way to package what was already happening as a result of Russia’s “lost years” when its energy intensity actually rose slightly after the Global Financial Crisis when oil prices shot back up and then declined very slowly headed into the 2014-2015 oil shock, which would once again not encourage efficiency investment since input fuel costs for oil and gas were low on export markets. Current gains are primarily gains that were delayed by Russian policy’s past inefficiency while importer economies that actually consume and/or manufacture goods for export kept getting better at using less energy per unit of GDP. But even a toothless plan is a change from no plan at all. MinEnergo expects the cabinet to rubber stamp a plan to support power plant modernization through 2024 very soon (possibly today/this evening). I’m watching to see what they do next. It’s one thing for a company like BP to begin courting the destruction of its equity value by reinvesting its oil & gas earnings into greener ventures in the often vain hope they’ll yield better returns in the long run and investors will stop barking at them. It’s another for an entire country to destroy a large part of its equity base, especially when its financial markets — a crucial driver for the energy transition — are still underdeveloped relative to more developed economies. Without a larger fiscal spend on investment and the willingness to embrace volatility as a necessary part of shepherding firms through the transition, energy efficiency gains amid what will likely be lower average hydrocarbon prices is the only way. Companies in Russia will kick and scream without more help. That means more subsidies. Next thing you know, subsidies are actually destroying economic value extracted via severance taxes and MET on oil & gas. It’s a cluster**** waiting to happen if they don’t get real. Or else they’re sticking to their hydrocarbon guns, which may stabilize the country’s finances and sectoral balances, but will kill what’s left of long-run growth within the current economic model. I’d love to be a fly on the wall in that cabinet meeting…

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).