Top of the Pops

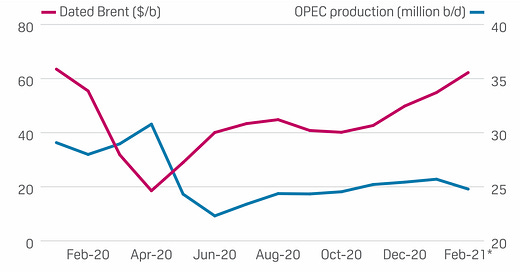

Saudi Arabia led OPEC+ to commit to maintain the existing cuts for longer, hoping to squeeze more out of the latest oil price rise while giving Russia leeway to increase output in April. It’s evident since the cuts took effect that they’ve done a good job of clearing excess stocks and shifting prices higher:

Brent broke $67 a barrel with oil futures up 5% after the cut extension was announced. That’s great news for Russia’s budget and for the oil firms trying to make up for some of the steep losses they suffered last year since the ruble’s not moving up with oil prices. The next hurdle comes as not all shale drillers in the US are equal. Publicly traded oil firms operating in the Permian basin and other US shale plays keep promising capital discipline, opting to focus on return for shareholders instead of output growth at all costs. Privately-held shale firms are under no such obligation to please investors, though they do have to generate enough cashflow to keep operations afloat. Firms like Pioneer as well as OPEC itself have done an admirable job communicating the expectation to the market that shale is no longer a threat to market stability and OPEC’s privileged position. There’s truth to it. As we can see from Baker Hughes rotary rig count data, it’s mostly international production showing changes going into March:

But if we assume that shale drillers have gotten average breakeven production costs down to $45 a barrel, particularly for the Permian, then the current trajectory of oil prices towards $75 a barrel would produce $30 per barrel of free cashflow, more than enough to finance further operations. There’s little doubt that this year, shale drillers will be chastened by the last year’s insanity, but OPEC knows that the closer the market returns to normal demand, the less incentive those drillers have to wait it out, especially if the underinvestment in upstream project globally gives shale another year to meet any change in marginal demand since most greenfield projects take years to provide returns. And then decline probably permanently sets in — I’m leaning towards thinking we’ll know enough about the macro picture by 3Q-4Q this year to make decent sense of when that starts. Impossible to know yet what impact working from home, for instance, will have on OECD demand.

What’s going on?

MinFin plans to cut further OFZ bond issuances by 500 billion rubles ($6.7 billion) saw trading indices for Russian sovereign debt tick up slightly while Russian corporate debt didn’t budge. The plan now is to issue 3.7 trillion rubles ($49.6 billion) through the rest of the year. Any reduction in issuances to the primary market i.e. where the securities are actually created and directly sold will drive up demand on the secondary market i.e. where investors trade with each other. Why? Well, everyone wants a sure bet and yields are decent compared to most sovereign debt held in the OECD (though inflation is obviously a concern). Since oil prices are rising, MinFin has less of a need to issue more bonds — as noted by the article, any increase in the nation’s current account surplus directly benefits the budget. But investors are probably mostly responding to inflation expectations in the Russian economy — higher inflation means that bonds with coupons pegged to inflation lose less of their underlying value per their price in relative terms than securities that aren’t performing well and lower inflation makes them fine balancing out a portfolio. Geopolitical risks remain since it was leaked that the US and UK were considering sanctions on sovereign debt but by appearances, OFZs remain a safe play. So long as yields are higher than the key rate, they’ll be attractive. The state’s finances are looking good for 2021 with more room to borrow and spend if they had the will to do so.

2020 data for WTO consultations, arbitration panels, and appellate body hearings show all three were at a quite noticeable low for the decade. It comes as a (slight) surprise given the potential for trade dysfunction as countries scrambled to ensure domestic procurement of needed goods, including PPP, but at least the US has shifted stance on it after Biden unblocked Nigerian ex-finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s bid to head the body instead of a ham-handed attempt to give it the post to South Korea:

Blue = consultations Red = arbitration panels Black = appellate hearings

On the face of it, the international trade system mediated by the WTO actually held up well last year. But these numbers don’t really reflect a positive trend or good feelings between nations. The truth is that it takes a long time to adjudicate trade disputes, especially since for decades non-tariff regulatory barriers, subsidies, and similar policy instruments that are harder to assess and were, at least until Trump went nuts in 2018, the main challenge for WTO cases. Most member economies were scrambling last year to ensure access to PPE and deal with risks of food inflation — the liberalization of the global food trade has yet to truly happen and largely falls outside the scope of WTO commitments. So since the COVID shock was a demand shock rather than a supply shock, there actually weren’t as many areas for trade issues to kick off, most of the salient ones weren’t necessarily subject to hearing oversight (or else take a long time to filter through the system), and it’s hard to imagine there are that many governments with the capacity available to take these issues seriously while facing sustained domestic crisis. It’s unfortunate that Russia never made use of its accession to further liberalize its own trade. There’s little surprise there, but one of the realities of the political economy of such agreements is that domestic political actors and businesses often want to move forward, but need foreign partners to justify action to voters and to help provide a cushion and political rationale for the inevitable ‘losers’ from any deal. That’s a no-go for Russia, and a huge reason why its trade integration with China is actually quite lacking despite expanding turnover since the regime can’t risk a flood of Chinese steel and other imports.

E-commerce firm Fix Price raised $1.7 billion at its IPO in London with plans to expand the amount offered to $2 billion implying the company’s market cap is in the range of $8.3 billion with GDRs expected to trade at $8.75-9.75 per share. It’s the largest IPO abroad for a Russian firm since sanctions hit and 40% of investors were reportedly Americans looking for growth with few political risks. The capital raise is setting up a big business expansion. Fix Price makes it money selling goods at fixed prices to consumers competing for market share by swallowing more of the margin from price inflation and reducing overhead. The hope now is to open up 3,800 locations across Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan — note the latter has harmonized external tariffs with the EAEU — and ruthlessly exploit the lack of competition from the underdevelopment of the sector in neighboring countries. What’s more, fixed cost cheap goods are in high demand everywhere, especially with growth slowdowns and higher rates of inflation. The play is for growth to cement an edge, a plan that undoubtedly will appeal to foreign investors looking for growth opportunities on a fairly volatile securities market. It’s a good example of the advantages Russian firms enjoy from the size of their domestic consumer market and ability to scale relative to firms in other EAEU members or observers.

Interfax has reported that plans to finish construction of Nord Stream 2 have been further delayed back to September. The stoppage comes amidst a new push on the Hill in Washington to get president Biden to further ratchet up pressure on the project with sanctions and related coercive economic instruments despite earlier reports that Berlin was hoping to strike a deal to have sanctions lifted. At least 18 companies have walked away from the project in the last week thanks to sanctions pressures while it emerged yesterday that a second pipeline laying vessel would join the project. German firm Uniper is warning financial partners that it’s possible the project will never be completed. It also came out yesterday that German banks had suddenly refused to work with Russia Today, potentially meant to signal to Washington that they’re serious about Moscow but want the pipeline. NS2 continues to be a domestic political football in the US as a result of Moscow’s stupendously short-sighted decision to tip its hand regarding the 2016 election, even if its actual interference was on a more limited scale than implied by Democrats’ outrage and frequently comparable to the tricks used by other powers including Saudi Arabia and the UAE to try and swing the election for Trump. It’s very difficult to imagine this project is truly dead. If it’s never completed, however, it augurs a less independent European foreign policy than the conversation in the policy world has suggested since 2017. Few people in Europe want to admit they remain dependent as ever despite a lurch towards greater fiscal coordination and fiscal/financial integration while those in Washington often need to keep threat perceptions of Russia and stakes in conflicts like Syria going to help justify the continued over-deployment of military resources to the continent despite its ability to provide for its own defense. There’s also clearly an effort from the State Department to try and get more money to Ukraine in return for reform progress. I do wonder what we’ll have left to talk about when this thing is finally over.

COVID Status Report

There were 11,024 new cases reported as well as 462 deaths. Mishustin’s set a public target of completing the mass vaccination campaign by the fall, which doesn’t exactly betoken stellar performance either for vaccine manufacture or distribution and take-up in the cards. That really needs to change to better absorb the ripple effects of last year’s economic policies. SMEs have seen their net indebtedness rise 20% year-on-year to 5.8 trillion rubles ($77.9 billion) with debts at an 8-year high — the last peak was 2013 after 3 consecutive years of post-crisis lending growth from commercial banks. The debt overhang will ripple out into pocketbooks for a lot of Russians if infections, even if lower, still affect the country. In that vein, it’s interesting to see Levada’s polling results when it asked people if they thought that respondents were completely open about their feelings about Putin when asked:

Red = practically everyone’s honest Orange = a majority are honest Green = half are honest, half aren’t Light Blue = a majority hide what they think Dark Blue = practically everyone hides what they think Grey = hard to answer

A net minority of the public polled feel that most people are honest in these surveys. This confirms what we generally assume about polling — it has to be read in a highly critical fashion. The higher oil prices rise, the easier it is to justify a big spending bill to try and shore up these figures that don’t really connect Putin to any of last year’s mayhem. It’s Mishustin’s time to shine.

Not Trade Away

In a move that surprised me, the Eurasian Economic Commission just announced that third-country tariff preferences shared by all EAEU members for external trade for a whopping 76 countries would be eliminated. Turkey, China, Brazil, and South Korea all escaped the policy change. To sell it, the Commission made reference to the fact that the existing system of preferences de facto reduces competitiveness of domestic industries. At the same time, exclusions from the full tariff rate for a total of 75 developing countries and 2 developed countries — they weren’t named — are under consideration. Per the logic of the new policy, countries defined as low-income or lower-middle income by the World Bank are eligible to receive preferences saved for developing countries. The only reason that the policy change will have such a small effect on the economy is the fact that so many developing economies don’t export any goods Russians (or others in Eurasia for that matter) want to buy from them or else export commodities Russia, Kazakhstan, et al sell abroad themselves. But what exactly is the EAEU thinking by imposing a greater hurdle for developing economies to trade on a preferential basis when it poses little threat to existing trade or competitiveness?

I argue it’s actually part of the bloc’s slow, painful maturation (though no one should be fulled into expecting the kind of integration pursued by the EU). Recently, the Eurasian Commission is apparently looking into a the implementation of a universal ban on single-use plastics across all member states to be studied with a policy review to be published soon. It’s a small change, but the kind of policy harmonization that provides a base for future cooperation — it also theoretically nudges petroleum products demand downwards ever so slightly. Businesspeople met recently at the Eurasian Pharmaceutical Forum to discuss the unintended consequences of misaligned national policies to ensure access to medications that end up creating barriers for other member states, a hot topic given medication price inflation across Eurasia has gotten bad, worsened by price control arrangements and poorly designed localization policies. The hope is to bring regulators into better dialogue with business. The situation in Karabakh has also created a new impetus to talk about rail transport across the South Caucasus, particularly linking Yerevan to Moscow via Azerbaijan and expanding transit links in the even that Turkey opens its border with Armenia. And all of this before considering the likelihood that Uzbekistan slowly moves from observer to member in the years ahead while using outreach from Washington on Afghanistan — again, the US appears there to stay for now — as a means to get Moscow to expand its cooperation in other areas. Any trade deal with Iran, if finalized, is a bit of a side show because of the ill-suited complementarity of the structure of the Iranian economy with that of Russia and other EAEU members aside from Iran’s persistent grain import requirements. But an unintended consequence of the war in Karabakh — and Turkey’s expanded role in the South Caucasus — is a greater potential role for the EAEU in future trade flows.

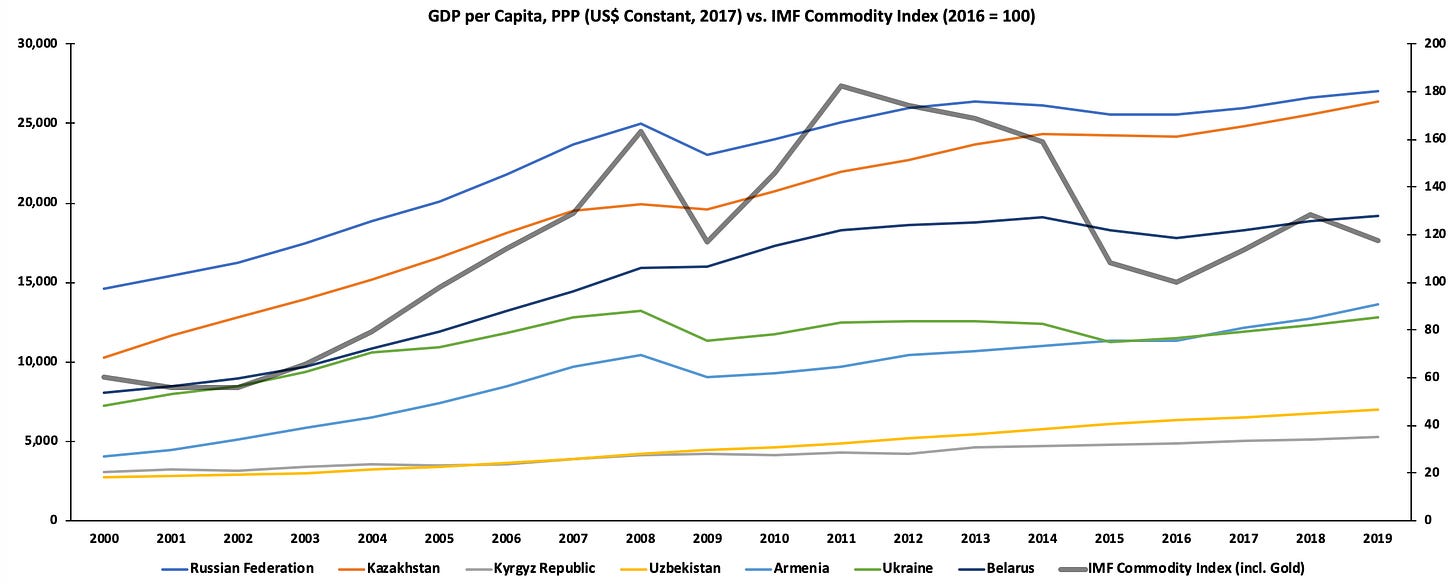

The biggest problem with the EAEU isn’t its often ad hoc nature or lack of depth for integration. Rather it’s the structure of the economies involved and primarily Russia’s failure to support its consumption levels and the role that its current account surplus plays in configuring not only its macroeconomic stability and budget, but in the imagination of its policymakers:

As we can, the relative growth in output per capita (which closely tracks with income per capita) structurally follows the commodities super cycle that erupted from 2003-2008, continues at a diminished pace from 2010-2013, and then again slows structurally with some difference on a national basis such that the commodity cycle is less and less important to determine growth outcomes. It’s exceedingly difficult to build a convincing trade union when its member states are, in the aggregate, commodity exporters whose business cycles and domestic consumption often has to be suppressed in hopes of warding off excessive inflation, the overvaluation of currencies, and economic volatility with swinging commodity prices. The EAEU as project failed before it had even been proposed in 2008-2009 when Russia’s response to the economic crisis did nothing to alleviate the underlying fissures that had developed as the economy exhausted excess Soviet productive capacity and capital goods, grinding to a halt by 2013 as the workforce began to shrink at the same time after 2010. What the EAEU is well positioned to do, despite all of these factors, is to create a shared market for consumer exports that otherwise can’t compete in the West or China. That doesn’t produce particularly robust growth unless real incomes are rising across the large enough swathe of the collective population between all of the member states. Russia’s by far the largest available catalyst for such change. If we take Russia’s official data at face value and revisit the problem/’riddle’ of labor productivity in Russia growing more quickly than in Russia than Europe, we can see this problem of income and consumption levels within Russia — and therefore the EAEU — more clearly:

Roughly 6 million “high productivity jobs” had been created since 2011 pre-COVID at the same time the workforce had declined by about 4 million people. Back of the napkin, that’s an increase of % share of jobs from around 18ish% to over 27%. Yet real incomes are falling and nominal wage increases aren’t cutting it. Basically, the issue in the Russian economy isn’t the productivity of its labor, it’s how much income is accruing to that labor in real terms — this is an institutional and political problem/choice, not a demographic one. So real incomes are too low and worsened by the obsession with the current account surplus, which shouldn’t be as important if the budget is truly moving away from oil dependence as is the economy per the sunniest reports put forward from Moscow, its ministries, and western business boosters who love to be contrarian. The inability to solve this conundrum then ends up hurting other EAEU members’ ability to diversify and create new opportunities for export by leveraging their comparatively lower labor costs (Kazakhstan excepted) and shared regulatory frameworks to relocate or develop supply chains Russia’s currently obsessed with localizing into EAEU member states instead.

Despite this persistent failure, there are still opportunities to be explored and more work being done. Some of this could well intensify since Lukashenka and Belarus’ government have every reason to pursue deeper integration within the Union State, which inevitably affects the expectations of other EAEU members. Azerbaijan and Turkey now have a preferential trading agreement in place as of March 1, which Armenia could benefit from (at least for transit) if talk of opening the border is serious. Kazakhstan’s senate just ratified a proposal to unify livestock breeding regulations across member states in hopes of harmonizing standards, thus making cross-border investments and trade simpler since firms don’t have to fuss as much about local regulations. The EAEU’s failings are ultimately rooted in Russia’s macroeconomic policy and, by extension, the limited space for other states to benefit constrained by their own political economies as well as the lack of opportunity for domestic business lobbies to force governments to act. But underneath the surface, work continues to better integrate trade practices for a set of economies faced with the prospect of shared structural stagnation due to the growth pathways and policy choices taken by Europe and China. It’s better than nothing, and still worth taking seriously instead of literally.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).