Top of the Pops

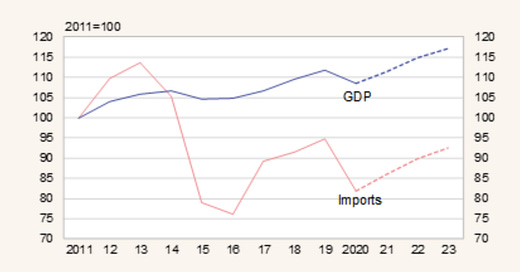

BOFIT’s forecasting that consumption levels will return to their 2014 and 2019 levels by 2023 as Russian growth slows in 2022 onwards. You can see that reflected in their GDP vs. import level forecast. The import gap below would partially be off-set by greater domestic production levels, but as we’ve seen, higher levels of non-value added exports tend to correspond to the domestic market’s inability to consume production because of stagnant or falling income and investment levels:

The fact that imports are now down over 15% vs. 2011 levels perfectly captures the extent to which the balance of the economy is still dictated by the oil price and oil production despite the budget rule, floating ruble regime, and shift in monetary policy management of currency risks. Brent’s back below $65 a barrel thanks to the uncertainty generated by the EU’s disastrous vaccine response and, thus far, inadequate stimulus spending levels. Rystad Energy estimates that up to 1 million barrels per day of recovered demand is at risk for the year due to vaccine setbacks. European refiners are feeling the pain on diesel margins now that US refiners are able to ramp up product runs, aided by vaccines and the recent stimulus bill, reducing import levels in the US from Europe. The weakness of European economies depressed domestic demand — diesel demand tends to track very closely with GDP since its used as the primary road fuel for deliveries of goods and, more so in Europe than the US, for light vehicle fuels as well. Russia’s budget is safe for this year, and we should expect more mild recovery if production cuts can be eased beyond what Saudi Arabia does in April. But the lesson here is that oil could end up dipping back down below $60 a barrel depending based on sentiment. The lower oil dips back, the weaker Russia’s import recovery. But import recovery is a weaker proxy for consumption recovery than in the past since real incomes are still lower and it’s exporting sectors that frequently import the most expensive goods, whether that be actual goods and services for their businesses or else SOEs and parastatals funneling luxury consumer goods to their managers. Overall, BOFIT’s forecast seems logical to me. I’m more skeptical, however, of the GDP/import growth paths after 2021, thanks in no small part to the much greater degree of uncertainty about the oil market and oil price in 2022 than I think the market’s currently baking in, especially since a spike later this year could shatter the discipline of shale firms trying to please Wall Street bankers.

What’s going on?

It’s expected that the 0.25% rate hike from the Central Bank won’t have a very visible impact on the cost of credit, at least not yet. For now, the new line is that the Bank of Russia is returning to a neutral monetary policy with a target rate range of 5-6% by year end. But the reason why is the tell. Banks are already raising average rates for borrowers in response to inflation and default risks, so the shift is a psychological nudge to the banking sector to start cutting credit risk levels. That seems likelier than not to help deflate some of the property bubble as well as explosion of consumer borrowing, all of which of course further weaken demand recovery across the economy. Nabiullina’s public assumption is that inflationary pressures are a result of demand recovery, then strengthened by two factors: much higher savings rates as people look for stuff to do with their money and the 2 trillion rubles ($26.83 billion) on foreign travel that went unspent last year. Given the additional savings since 2019, we’re talking about an additional 4-5 trillion rubles ($53.66-67 billion) in additional money to be spent. Where Nabiullina’s story falls apart is that she cites rising purchases of goods with a long use-life as driving up inflation. However, the price inflation we’re seeing is happening for food and housing most strongly and producer inflation has outstripped consumer inflation the last few years. Add in how weak the lockdown measures were and it becomes apparent the Central Bank’s own theory of what’s happening can’t fully explain what’s happening. There’s significant demand recovery — not really a result of vaccines’ success — but it seems likelier that the mis-utilization of existing productive capacity is happening alongside continued belt tightening for most Russians, which means that the consumer recovery is being led by those who are better off. Their appetite for new physical goods will run out at some point before a full recovery materializes.

Rosstat’s statistical review for Jan.-Feb. shows that the construction sector is back on trend and pace without any interruption. The Kommersant coverage notes that construction of 5.5 million square meters’ worth of space was completed in February, a 10.8% increase year-on-year when COVID just began to have an effect on the Russian economy. MinStroi’s Irek Faizullin is claiming ‘victory’ and the success of the state program last year to subsidize spending for construction firms. The following shows the volume of working being done in the sector going back to the start of 2019. It mirrors the overall trend for build starts shown by Kommersant ripped from the same section of the review:

Green = general volume Yellow = excluding seasonality Brown = trend

An estimated 56% of construction projects currently underway are making use of the ‘stimul’ program offering the subsidies. The expectations are now that building will continue on pace, though total area built may lag 2020 in the end. What I find fascinating about the consistency of the data is that no one seemed to think a mortgage subsidy program wouldn’t trigger a supply/demand imbalance given that net construction has been at the same level for years and sticks to a fairly stagnant trend. If their idea of recovery is the same performance as last year while regions see rising deficits of new builds, then there’s a growing body of old capital stock Russians would rather see replaced and a lack of new capacity to absorb the newer, riskier buyers. As I suspected, they’ve engineered a property bubble worsened by their attempts to ‘command’ the sector through formal and informal mechanisms.

Andrei Belousov is back at it trying to fix the much-maligned SZPK investment contracts in a new effort to ‘clarify’ possible source of private investment into major projects. The government is now proposing a list of 32 measures through 2024 intended to funnel some money from banks to legal entities engaged with said projects to crowd in private sector money. As usual, the long-term stimulus discussion entails supply side measures via tax breaks to increase investment. The current roadmap battle for the SZPK investment vehicle is, being generous, a farce. On the one hand, a bunch of measures put forward by both MinEkonomiki and the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs are included, but being renegotiated as always. On the other, one of the most coveted supply side measures — allowing firms to acquire ‘privileged’ shares of projects and keep them — reveals the real thrust of negotiations. Only the largest companies with the most in hand to invest or best relationships with banks can raise the levels of capital the Kremlin is hoping to funnel into productive investments. Their real concern is being able to protect their investments given how rowdy, litigious, and otherwise administratively violent business disputes can become. The only way to do that is to secure control of a key public good or rent flow. That so much focus is now being placed on working out new instruments to finance these projects reveals that the cost of credit is part and parcel of this challenge. You’d think they’d entertain keeping monetary policy easier in exchange for productive investment, but instead, they’re trying to find ways to ‘de-risk’ borrowing at the state’s expense. Worse, businesses are now trying to swap property taxes/severance tax breaks for higher income taxes, which would screw regional budgets. Businesses are trying to use the center to ram through improvements for their returns in the regions and consolidate control over key assets while the center is trying to coax out business investment through a variety of incentive measures. It’s a recipe for policy disaster.

Penza governor Ivan Belozertsev has been arrested on charges for taking bribes, announced formally by the Investigative Committee. Boris Snigel’, the head of pharmaceutical firm Biotek, reportedly bribed Belozertsev to the tune of 31 million rubles ($416,640) to win ‘competitive advantages’ i.e. preference for procurement contracts, speedy authorization for builds or investments etc. Investigation quickly showed that Snigel’ provided a Mercedes Benz V250d and Breguet watch as gifts alongside 20 million rubles ($268,700) of cash bribes. An additional 500 million rubles ($6.72 million) were found searching his home. More has to drop before too much can be gleaned, especially since these cases are often up to internal spats and rivalries as well as the incentive to make sure a visible figure suffers the consequences to keep up the public appearance that anti-corruption efforts are a serious state commitment. Novaya Gazeta offers a bit more coverage akin to a play-by-play. What I’m curious about his what Biotek was doing and the fact that the case helps create the impression that the pharmaceutical firms are exploiting the public during a time when medicine price increases have outstripped topline inflation and everyone’s trying to get over the collective impact of COVID since medical spending shot up last year. Weirder still, the Penza regional government apparently doesn’t have the legal authority at the moment to relieve Belozertsev of his post so he’s still acting governor despite his arrest. The spin on this will be interesting, and my gut feeling that the longer the inflation crisis goes on and the more the Kremlin commits to the idea that price increases are happening because of ‘non-objective’ causes or manipulation, the more likely public arrests will be made on these types of charges.

COVID Status Report

New cases came in at 9,284 and reported deaths at 361. The case load remains stable with more evidence that the decline has plateaued, which should worry anyone concerned about newer variants and international travel. Aside from the worst hotspots, European Russia continues to improve:

On the plus side, MinTrud has announced that it may continue to provide subsidies for employers aimed at boosting hires among the currently unemployed to help them transition to remote work, up to 50,000 rubles per job created by the employer doing the hiring. That could help nudge along some efficiency gains at the firm level and perhaps help create more jobs using state resources. More interestingly, the pandemic and the various support measures, including bans on the use of transport for the elderly or remote working regimes, appear to have left a sour taste in the mouth of those aged 56-65 who, per VTimes reporting, express the highest levels of dissatisfaction with their daily lives of any age group. That’s probably caught the eye of domestic policy curators trying to get ahead of September given how important a voting bloc that age demographic is for the regime. Only 14% of the demographic believes nothing has changed for how their family lives while, oddly enough, the 18-35 year olds express the highest belief that things have gotten better for their families. As demo, it also had the highest % say they had to tighten their belts — 56% — though the other demos all had results above 50% as well. The socioeconomic stress of the pandemic and the regime’s policy responses appear to have hit those who aren’t yet retired yet, but are nearing it the hardest, at least per polling. Who’dathunkit.

Dollar Dolor Bill, Y’all

Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov set off a round of mild questions and speculation in Moscow when he implored his Chinese counterparts while visiting Beijing to work with Russia in abandoning use of the US dollar and western payments systems. In trumpeting success with de-dollarization, coverage notes that Russia has liquidated virtually all of its holdings of US sovereign debt, reduced US dollars to 20% of all currency reserves, and shifted the pricing denomination for many of its resource export contracts such that only 49% of all resource export earnings are now in dollars vs. 80% in 2013. Adding some fuel to the fire, Kremlin spokesbro Dmitry Peskov added speaking with the press that Russia couldn’t exclude the possibility of being cut off from SWIFT in its policy planning. US sanctions activity was painted as ‘baseless’ and ‘unpredictable’. The obvious truth of the matter, however, is that these efforts are entirely political, not particularly intelligent policymaking, not mirrored by Russia’s private sector, and of asymmetric interest to China given its massive trade with the US and EU.

In December, ING did a great roundup on the state of de-dollarization in the Russian economy to highlight the gap between the public and private sectors:

Non-financial international assets denominated in dollars kept rising, dollar deposits at local banks in dollars increased slightly. If you use the World Bank database for growth figure (acknowledging that adjustments render GDP output growth data from Russia frequently unhelpful), by the end of 2020, the economy was basically the same size as it was in 2013. There was actually more growth in dollar deposits than broader GDP growth in % terms since 2013. The decline in bank loans denominated in dollars probably has more to do with reduced export currency earnings in 2020 than actual diversification and the daily FX market turnover also reflects lower demand. While USD oil prices still dictate the volume of export earnings and trade and financial structures with the US and EU haven’t changed that much, the real progress for de-dollarization has come in Sino-Russian ties. The two following graphs tell the most important stories — the Euro’s rising share of exports to China and ruble/yuan’s rising share for imports from China:

China’s become a massive source of foreign Euro earnings for Russia Inc. while Russia’s importers have been trying to expand the % share of settlements in rubles and yuan, presumably with the accent on the former. Lavrov’s entreaty is pro forma and not to be taken seriously, but cuts to the problem Russia has when these types of talking points are rolled out. Russia isn’t actually an economic great power, even if you use nominal or PPP adjusted measurements of GDP, and so long as its hostage to commodity export surpluses maintained, in part, by suppressing domestic consumption, its currency is never going to internationalize in the manner I think the political actors pushing these ideas hope. The most obvious reason being that China exports far too much to the United States and needs access to the liquidity provided via the US dollar as well as safe financial assets for its own macroeconomic management. Look at the relationship of the USD/yuan exchange rate, Yuan/ruble exchange rate, and oil prices for Brent crude between Jan. 2020 and February this year:

China actively manages the exchange rate to avoid volatility against the USD, whereas we see a lagging relationship for the ruble and yuan relationship. The yuan steadily strengthened over the course of 2020 against the ruble, most likely because of shift from bilateral trade deficit to surplus with Russia by 4Q last year. This dynamic only reversed once oil prices climbed past the $60 a barrel mark and while muted via the budget ruble and other forms of monetary management, confidence in the ruble tends to pick up thanks to higher prices. But because of the USD/yuan relationship, Russia doesn’t really achieve de-dollarization. Rather it outsources the task of managing USD liquidity, exchange rates, and access to its trade partners, particularly since Russian firms still buy dollar-denominated assets. The de-dollarization campaign highlights just how little power Russia has to effect these types of outcomes, a dynamic intensified by its commodity export dependence. What’s worse, it leaves Russia open to greater dependence on the yuan, which isn’t really a great bet.

The biggest advantage the US dollar has on every other currency these days is the Federal Reserve. Setting aside elite preferences to use them or store wealth in dollars and the various historical contingencies that pushed the dollar to the top of the heap after the collapse of Bretton Woods, the Federal Reserves’ (relatively) successful balancing act backstopping global liquidity in 2008-2010 and during the COVID crisis have reminded everyone no one else can conceivably challenge the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. At the same time the United States has reasserted its role as a currency hegemonic, China faces a very different challenge than it did in 2008-2009. It has to continue to open up its capital account and financial markets while managing massive systemic risks from a country with a financial system that can be madly opaque. The currency and policy risks around yuan use are a lot different than the dollar. When Vyacheslav Volodin tries to get the Duma in on the act of raging against the dollar’s ‘monopoly’ in the global economy, they seldom seem to recognize that not only is a nearly universally agreed upon safe asset and store of value crucial for economic stability, but that the rising role for currencies like the yuan could destabilize the Russian economy. For instance, recent declines in property values in China’s 3rd tier cities have led to lower levels of consumer spending, suggesting a considerable ‘wealth effect’ flowing into household pocketbooks from fluctuations in property values. But values keep rising in 2nd and 1st tier cities in a manner that’s not sustainable given wage and income growth without continuing to inflate a massive bubble of privately-held debt linked to rampant speculation. Any future decline would then ripple into consumer spending, triggering yet more debt to maintain growth. What’s more, the value of those assets is strongly affected by fluctuations in the value of the US dollar because of the yuan’s ‘soft peg’ to American currency. The value of the US dollar — and the large amount of Chinese exports traded in dollars — affect demand for yuan, and therefore its value (and the value of said assets). Rising property values provide much needed revenues for China’s regional and local governments since they can raise tax revenues on land and are therefore happy to fuel speculation. Does Russia really want to swap a direct use of the dollar with the stability it affords, despite its political risks, for greater risks of instability from a dollar-pegged currency and economy saturated with speculative assets accruing far too much value and impact on household spending? Probably not. But the yuan is the only major option left, and one that actually just reconstructs the effect of the US dollar on the Russian economy without escaping it. No matter what Lavrov says, oil and the US dollar dictate far more of Russia’s economic fate than it admits.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).