Top of the Pops

The notional ‘bond vigilante’ has long vanished. Much like the Federal government tamed the gunslingers of the Wild West, central banks have squeezed out space for private holders of bonds to play God on bond markets as speculators. We’re entering new(ish) territory now as central banks in developed economies change the playbook looking for better ways to manage massive piles of debt and assets to prevent financial instability. The Bank of Japan is now the biggest owner of stocks in Japan, holding $433 billion in its equity portfolio and distorting (raising) the value of assets held in equities, much like quantitative easing measures crushed bond yields by raising the relative value of bonds as an asset:

Now that central banks are increasingly invested into equities, they’re stuck playing the role not just as a lender of last resort, but a market participant maintaining demand in a situation where capital has been plentiful but poorly allocated for decades. It’s one thing to dive into the geopolitical consequences of the Fed’s actions in 2008-2009 and this year in terms of swap lines and maintaining dollar liquidity, another to consider what the growth of central banks as equity players could mean for the energy transition. Many have called out the shibboleth of central bank independence since monetary policy cannot be neutral and, by definition, has massive distributional effects that are political in nature. The question I have is how do equity interventions interact with commodities markets and investor expectations? If central banks buy up ETFs and many of them are linked to cyclical commodities and sectors, what does asset price inflation there do for company performance, ability to raise capital, commodity futures, etc.? Geopolitical fault lines of the post-COVID recovery will be shaped in no small part by fiscal and monetary capacity. Developed economies’ central banks are innovating and changing their role on the fly. The next logical step would be directing those equity interventions to achieve political ends, like rewarding greener companies and so on. That will leave Russia and commodity exporters in the cold if they can’t alter the distribution of economic output domestically.

What’s going on?

RZhD is telling the press it’s 1.19 trillion rubles ($16.27 billion) short for its investment plans 2021-2025 for new builds and modernization. That’s a shortfall of about a third of what it needs, and the monopolist is hoping for 500 billion rubles ($6.83 billion) in authorized capital from the state, of which 289 billion rubles ($3.95 billion) would finance modernization for 2022. There are ancillary funding plans to sell off foreign assets to raise a little capital as well as cancel the dividend payout for 2021, 2024, and 2025. RZhD always has trouble financing its investment plans given that Russia’s infrastructure needs require massive capital allocations the state continues to refuse to meet, both due to tight fiscal policy as well as the reality that budget overruns from uncompetitive tenders and cost inflation are a problem everywhere. With interest rates lower now, taking on more debt is an acceptable means of meeting financing needs. This story’s just worth a look cause it’s a persistent problem — the revenues generated by tariffs for use of the network and the way tariffs are held down for lots of bulk cargoes and commodities creates a constant push-pull to prevent consumer inflation from transport bottlenecks.

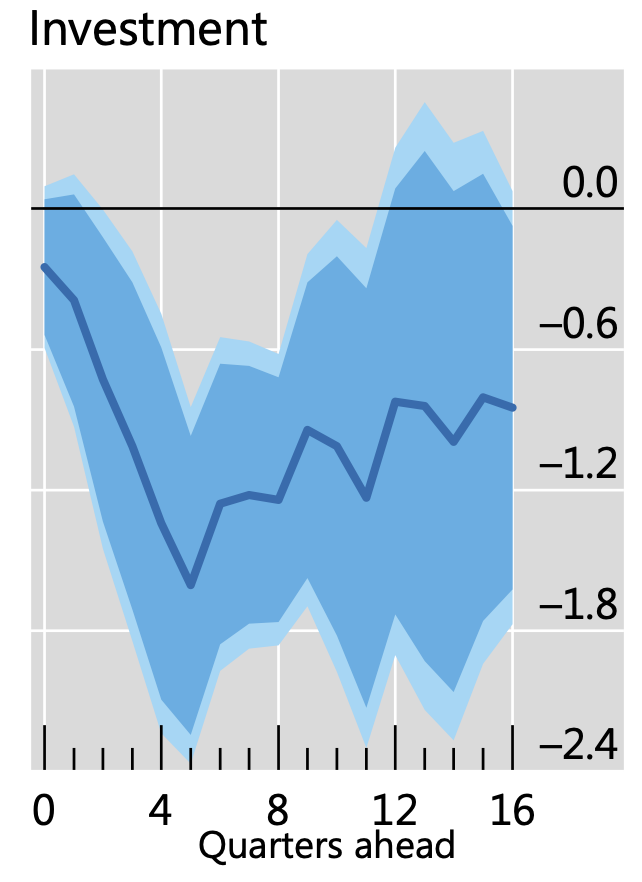

The Kremlin’s playing the part of “happy warrior” messaging that it’s not as pessimistic as the economists about a continued slowdown and potential economic contraction next year. It’s hard not to see the statement put out by Peskov as tone deaf, even if its true in strict GDP terms (but not when you factor in the composition of GDP). The Bank of International Settlements released its quarterly review on the US dollar and emerging markets yesterday, flagging the risks of dollar appreciation (the following comes from a breakdown of the percentage impacts of a 1% appreciation for EMs using data from 1990-2019):

Most EM consumption is insulated from big changes due to an appreciation (less than .5% decline) and Russia is also insulated somewhat by its use of Euros (Euro appreciation tends to help EM exports and counteract some USD appreciation effects). But the fall in investment into EMs globally if the dollar stays stronger or appreciates upwards again — still an if given Fed policy thus far — will feed back into commodity demand and hurt Russian growth. As Adam Tooze has pointed out, it’s now “the rest” and not the world’s leading economic powers in the driver’s seat to reduce emissions given they contribute a majority of them globally. Commodities demand is an emerging market story along with China’s Death Star-like pull. Risk-off for underlying risks to equities means more investors are going to want the dollar as a safe harbor late in the year.

National projects have received 78% of their planned budgetary outlays for the year through November, showing considerable improvement over last year (74.8%). Vedomosti’s reporting that lots of contracts have been closed in a 4Q scramble to meet targets is encouraging. The real story from what I can glean is that spending on the National Projects received more scrutiny and pressure politically to act as ‘stimulus’ by maintaining spending levels, one of Siluanov’s favorite tricks to convince Russians that the state is here to help. One of the areas of best improvement was spending on new housing, which hints that someone got the memo that a mortgage-led credit expansion would pressure housing prices (region and city depending). The longer rates are held lower, the more I’d focus on that aspect of spending.

The Duma is expected to pass a bill on first reading tomorrow that will allow Roskomnadzor to block internet “resources” that allow discrimination against Russian mass media. Heavy-handed and clumsy, the law is going to be used to go after YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, any western (really American) social media platform that restricts content from Russian media sources because of fallacious claims, misinformation, and more. The bill is the latest attempt to establish a truly sovereign ‘runet’ free of foreign interference, but I’d suspect the actual intended purpose is as much commercial. Just as VK beats out Facebook for its functionality and being an indigenous platform, this law creates a new legal instrument for Russian firms to challenge international incumbents. If they achieve enough scale, the loss of Facebook, Twitter, or related platforms doesn’t matter. No one is crying over LinkedIn being blocked for years now.

COVID Status Report

Daily cases fell to just over 26,000, though recorded deaths ticked up to 562 for the last 24 hours. However, the underlying data from the Operational Staff shows not just a big dip in Moscow (which has been quite noisy the last few weeks), but also the first significant daily drop in regional cases yet recorded (again, just a one-off for now but still noticeable). The regional breakdown for total confirmed cases looks decent:

The official data available shows that things seem to be petering out some in terms of the worsening situation across the regions, and things looks decent overall. They’re hiding how bad things are slightly by using total confirmed cases rather than rates per 100,000, but on the whole, the map has stayed roughly like this for weeks now. Yesterday, Anna Popova — Russia’s head sanitary doctor (akin to a surgeon general, but given Russia’s institutional chaos, not quite the same) — confirmed the rules for the transport of the Sputnik-V vaccine. It’s got to be transported and stored at -18 celsius. Cases are still rising, and public officials are still communicating concern as they should. Seems that some medical personnel, in this case in Buryatia, are complaining that promised payments for working at COVID hospitals haven’t materialized. There’ll be more of that soon, I expect, across the country. The rate that things are worsening has slowed down, but the curve isn’t flattened yet.

Swords without Dowshares

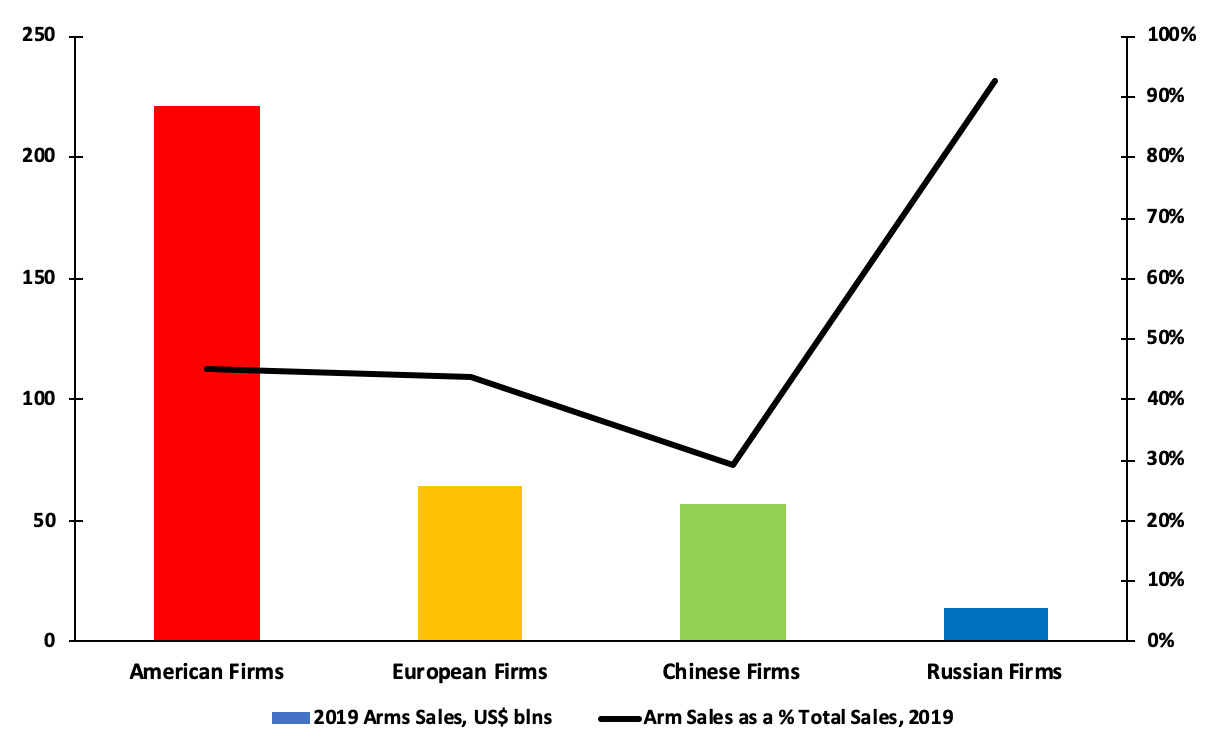

Scrolling yesterday, I chanced upon SIPRI’s 2019 update regarding the world’s leading arms manufacturers and, while I’m not a defense expert, it struck me when thinking through the political economy of Russia’s military exports and the role of the defense sector domestically. Since Trump came into office, there’s been slowly escalating pressure led by the US congress to codify defense sanctions and manage defense relationships for the US in such a manner as to try and reduce Russian firms’ ability to export to key partners. In many instances, exemptions have been offered by American authorities, but it’s a dynamic that fits into a broader shift in US policy posture to exert as much pressure as possible on Russia’s most politically sensitive industries.

Skimming over the data, the first point to raise is just how much ground Russia has lost to foreign competition when you break out the data at the company level. While SIPRI has clearly left gaps in its reporting, it’s still a useful reference point to start from. Note that given Russian procurements are denominated in rubles, Chinese procurements in CNY, and European procurements in Euros, these comparisons distort the picture significantly on a PPP basis — massively in Russia’s case — but are still useful when assessing the global arms trade, corporate incentives, and domestic lobbying and interests. This isn’t trade data, but rather net sales data from the top 25 firms globally. Only two are Russian — Almaz Antey and United Shipbuilding Corporation:

Russian exporters only accounted for 3.9% of global sales from the top 25 firms in 2019 per the SIPRI figures. The issue isn’t so much about total export volumes or Russia losing its export position (yet) on key markets such as India, where the US is consistently making headway. Rather it’s about the nature of the companies involved. For the US data, GE skews it quite a bit since military sales account for a very small part of its revenues, but on the whole, American arms manufacturers are more diversified than their Russian counterparts, as are European ones. Further, small and medium-sized contractors fulfill 50% or more of American defense procurement orders domestically, which speaks to how the defense budget in the US creates ripple effects for growth. Setting aside differences at the firm-level, this creates a long-run problem for Russian firms trying to maintain their competitive position globally against countries like the US and China that spend more on R&D, have defense firms that are diversified into non-military supply chains, and crucially have a broader economic portfolio and economic effects driving the lobbying interests of the defense sector domestically.

Because Russia centralizes its military procurements and production process into the hands of state-owned monopolies or oligopolies, there is a smaller multiplier effect for every ruble spent on defense compared to the US. Past measurements of multipliers in the US are fundamentally flawed in a post-2008 world: they assume that ‘automatic stabilizers’ kick in when it comes to fiscal policy, tax levels, and the budget deficit that end up taking money out of the private sector’s hands because of the classical assumption of a scarcity of capital. Money spent by the state today theoretically reduces what could be spent by the private sector due to various offsetting mechanisms. That doesn’t really make sense in a world of negative, zero, and near-zero interest rates and no evidence of fiscal consolidation in the US in sight. In other words, if the defense budget hits $1 trillion in the US — something I foresee as a very real possibility given the emergent consensus about maintaining a qualitative military edge over China — it may produce positive economic spillover benefits, though much of these would be canceled out by deployments, under-investment in healthcare and veterans’ services, and infrastructure because of mistake priorities as well as a concentration of rents via defense contracts in bubbles like the Washington D.C. metro area. Russia, however, faces a very different macroeconomic environment and set of assumptions for its spending (lhs is trillions of rubles):

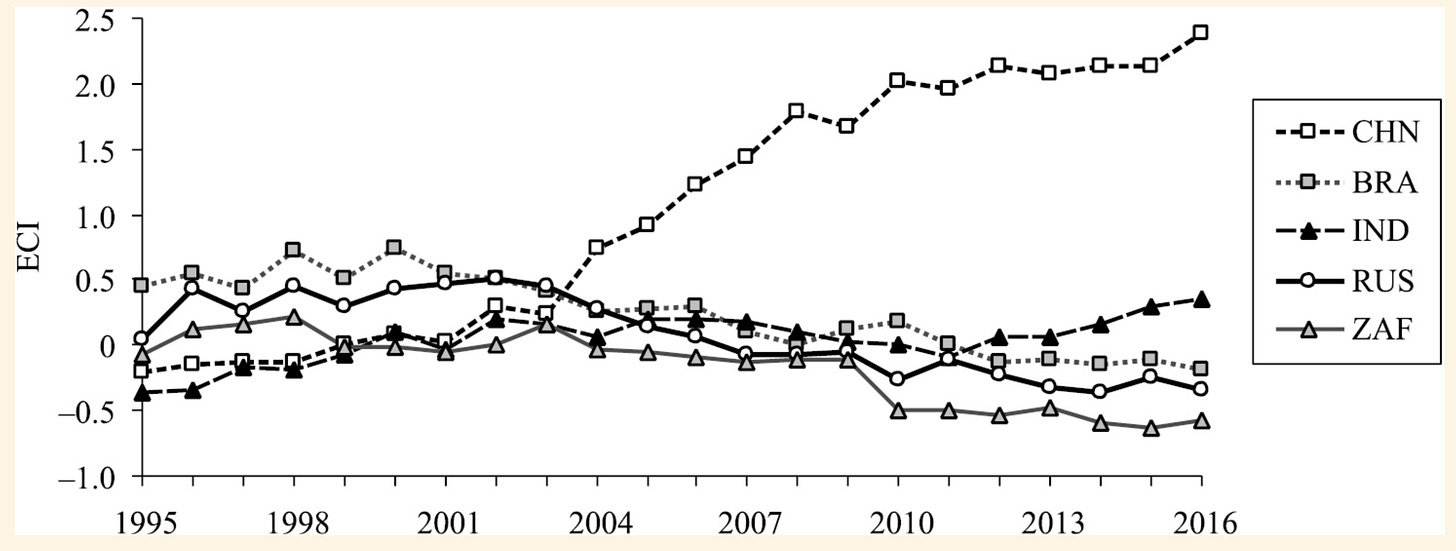

Setting aside that MinFin understates O&G revenues by only including taxes directly levied on extraction and production like severance/MET, an average of 2/3 of Russia’s “pure rents” raised off of the oil & gas sector finance official outlays for defense and security. But unlike the defense sector, oil & gas companies create an ecosystem of smaller contractors that, while frequently vying for contracts via state tenders, are not living off of the state budget, but rather corporate budgets. Military production faces the obvious demand constraint that it’s only the nation’s military or else a foreign military buying an import that can possibly consume the product, and the product’s use faces a very different set of considerations than, say, buying a computer or phone that will obsolesce within 2 years’ time to be replaced on schedule. Defense spending in Russia tends to follow this script: increases in defense outlays create future drags on growth by reassigning resources that would otherwise have gone into consumer production into the military sphere where their end use and demand is constrained by the budget and foreign budgets and agreements. In Russia, this is far more true than in the US, not just because of the simple fact that Russian defense firms aren’t as diversified but because Russia is an economy facing capital and demand constraints created or worsened by its economic model. Between 2000 and 2016, the economy became less diversified as a result of the over-weighting of the extractives sector in its economy:

Capital scarcity is now in flux. With the key rate as low as it can be before Russians start withdrawing all their money from banks and shoving it under the mattress or abroad and loan interest rates at recent historic lows, there is greater potential to support diversification through domestic demand. But whereas US military spending often goes to smaller contractors with plants located across a wide range of political districts and jurisdictions — part of what keeps the budget so high is that the NDAA is always a jobs bill — the economic gains from Russian spending are more concentrated economically. And because of fiscal consolidation, the state worsens capital resource constraints for the consumer sector by destroying demand, which is a necessary precondition for lending to SMEs and consumer sector businesses to make any business sense for banks. As a result, defense (and security) spending ends up acting more as a net drain on the nation’s oil & gas rents and wealth than an economic stimulus plan, can indirectly undermine the legal environment for intellectual property since security officials frequently try to securitize technological innovation, disseminate defense sector patents to non-military businesses and applications in an inefficient and economically unattractive manner, and capture rents that harm diversification initiatives.

This is especially important because industrial localization, which has taken place for the oil & gas sector across numerous regions, produces net positive effects for economic diversification among smaller firms. That’s not possible with the top-down approach taken by Russia’s military-industrial complex. This is where the initial chart showcasing the relative diversification of other firms (and defense sector participants) comes into play. When a US defense giant lobbies for a defense deal with India, a Gulf state, or Vietnam, it’s really a trade deal. Supply contracts generate work for smaller contractors, many of whom serve civilian economic sectors as well at the local or regional level. The additional revenues secured from these contracts can then sustain deeper diversification and growth on their part, acquisitions, investments into R&D, or expansions of capacity. When a leading Russian firm like USC or Almaz Antey close a deal, what it’s actually doing is providing revenues to lessen dependence on the defense budget. This applies to American firms as well, but most have secondary and tertiary revenue streams that make it easier to raise capital, sell to other markets, and more effectively lobby to protect their budget allocations because of the larger macroeconomic impacts. Russian firms generally don’t, or else have limited means to. Exports are therefore really about sustaining fiscal consolidation and reducing the net drain on scarce resources that would generate much better economic returns were they invested into infrastructure, used to expand SMEs’ share of the economy, and increase R&D budgets not just for defense purposes. Russia’s falling behind on that front, as I’ve noted before regarding R&D as % of GDP:

Ironically, American firms are arguably often better at protecting and raising defense spending and expanding their contracts because they provide broader economic benefits. Their Russian counterparts face much harder budget constraints despite being state-owned firms ostensibly able to borrow backed by a sovereign government compared to the US firms that face soft budget constraints enabled by cheap credit and scale. There’s no doubt that Russian firms will keep selling to historic defense partners like India, sell what they can to Middle Eastern governments looking for a better deal from Washington, and offer higher-end tech to China to maintain that relationship. However, it’s too lazy in my view to rest on past relationships. Take India. Even though the vast majority of Indian military equipment is Russian-sourced, the much broader array of industrial consumer segments American military manufacturers are involved in means that future trade and investment talks can advance without reaching expressly military deals. So can agreements over tech firms’ market entry. Over time, those become supply chains and a level of comfort between corporate entities, which then beget research and investment partnerships which then beget deeper ties than Russia selling off licensed platforms that may, in many cases, underperform what might be available elsewhere or else what China will be able to produce as its absolute investment into R&D continues to rise whereas it’s stagnant in Russia. The problem isn’t today or the next 5 years. The problem is the broader economic model underpinning how Russia uses exports to sustain the financial health of its defense sector, and how little that defense sector produces in the way of broader economic benefits. The world is dual-use now, and that is where America’s defense establishment has a decided edge in long-term competition.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).