Top of the Pops

Building on earlier news this week regarding OPEC+ cuts and US shale’s resilience, Rystad Energy put out a rough forecast for investments and cash flow in 2021. The big takeaway is that investments fall from 2020’s levels if WTI hits $35 a barrel and stay flat if it’s at $40 a barrel. Anything higher signals an increase:

It turns out that OPEC+ is still benefiting US shale. That’s what makes the market management strategy from the Moscow side more interesting in the coming 12-18 months. Last April, it became clear that those arguing internally (Sechin and Rosneft) that OPEC+ was just a protectionist scheme helping US oil firms were right, but terribly wrong about how well-equipped Russia was to handle the fallout of a massive market glut in the middle of a global demand shock. With this dynamic unchanged by COVID, it’s difficult to see Rosneft hitting targets of 100 million metric tons annually (effectively 2 million barrels per day) for Vostok Oil unless the sector fully idles older fields in Western Siberia that are more competitive logistically, if not necessarily on a breakeven price basis once export infrastructure is built in the Arctic, though labor costs will be higher due to regional wage adjustments per Russian law. However, transport via the Arctic — even with warming freeing up ice — is unlikely to ever be as competitive as pipeline exports or pipeline deliveries to Novorossiysk on the Black Sea or to Leningrad oblast’ on the Baltic. Much more difficult navigation and environmental conditions introduce much higher risk levels for trade insurers and, more importantly, the route lacks any ancillary ports of call to absorb cargo volumes when deliveries are swapped, a ship runs into trouble, and/or a buyer’s contract is frustrated. London is still the premier global market for insurance on these matters, a position of strength that is unlikely to be significantly affected by Brexit due to the City’s institutional advantages and strong premium growth in developed markets since 2015. I’m curious to see how British authorities react to rising cargo volumes, especially if the Tory government is forced to double down on a hawkish economic foreign policy as concerns Russia to buy goodwill with the Biden administration.

What’s going on?

RBK finally got around to doing a roundup on the implications of US elections for the Russian economy. As noted in the piece by my friend Max Hess from his work with Riddle last October, Biden’s policy team, views, and world all entail a commitment to broad use of economic sanctions and related levers of power to pressure Russia. However, I suspect the use of broad, non-specific sanctions rather than ones targeted to individuals or defense-related entities to be quite limited at the outset for the simple reason that Biden’s foreign policy focus is reassurance and rebuilding the US economy to compete. Still, Russia’s unsanctioned banks like Sber and VTB undoubtedly are considering their next moves in light of unified Democratic control in Washington. As the roundup notes, I agree that Biden would return to using the WTO as a positive forum for trade policy formulation, but I suspect that Trump’s trade policies are here to stay, in terms of aims if not the instruments used to achieve said aims.

From the end of December, just a useful reminder from Argus of just how good the commodities market looks for a bull run on everything that isn’t oil or gas:

A weaker dollar and China’s credit policies are spurring base metals to new highs, surely good news for Russia’s exporters, but a weaker dollar is going to be a problem for the Euro as it keeps appreciating. Remember that the stronger the Euro gets against the dollar, the higher the risk of deflationary pressures from a loss of trade competitiveness, particularly concerning since existing European stimulus plans do a poor job of generating more domestic demand to reflate growth. It could well help lift the ruble a bit, which of course then reduces some of the earnings gains Russian exporters would be making by selling in foreign currencies abroad while spending domestically in rubles. A lot still hangs on what Biden’s economic policy looks like post-inauguration.

Mishustin popped by Rostec to remind everyone that Russia will not be buying PPE from abroad because of its exports to get domestic production up to speed in the last half year. It’s thin gruel — there’s still not much out for news the day after Christmas after all — but it’s a useful reminder of how the regime has to sell its economic policies responding to COVID. It’s not that different from Trump talking about bringing jobs back, though in this case it obviously refers to a highly sensitive production chain other nations have taken similar steps to ‘onshore’, because of how important it is to signal that Russia’s leading SOEs and firms are removing the attendant risks of relying on imports from abroad. Chemezov noted that Rostec currently meets 33% of domestic needs and hopes to achieve 50% market share by 2025. In short, the crisis is yet another opportunity for SOEs to try and claim dominant market shares and weaken competition from the private sector in Russia, or else from smaller state concerns.

The government led by Mishustin has adopted a road map for the national development institutions — read: state-owned companies of all shapes and sizes — requiring them to publish publicly available documentation covering key performance indicators (KPIs). It’s the latest iteration of the ‘personal responsibility’ both Putin and Mishustin call for when haranguing others to achieve national goals dictated by planning documents. This latest twist in the name and shame approach should, in theory, promote more competition between state firms given that the public will be able to scrutinize the progress they’re supposedly making. What’s likelier, though, is that the companies will simply try to seize the formulation process for said KPIs, trying to buy favor within the presidential administration and cabinet to argue for KPIs that benefit themselves while hurting others. Twas’ ever thus.

COVID Status Report

The decline in cases seems to have leveled off — 23,652 new cases in the last 24 hours vs. 454 deaths. The regions and Moscow moved in unison for the first time in awhile:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

I suspect that some of the leveling would be expected from lagging data around New Year’s, but the situation would ostensible worsen considerably if the new strain reported from the UK — already in 22 European countries — spread to Russia where it would be considerably riskier for the jobs that hold the country’s export-oriented economy and its foreign currency earnings together. The relative silence of authorities is concerning, but not evidence of withholding. We’ll just have to wait and see. At the same time, there’s some bad news for Russia’s hopes to use vaccine diplomacy to maneuver with the EU. The European Commission has come out strongly stating that purchase agreements require negotiations with the the bloc, not individual countries, which will undoubtedly strengthen the position of those opposed to using the Sputnik-V vaccine on moral/geopolitical grounds.

The Color of Money

The FT ran a fantastic piece about the problem on BP CEO Bernard Looney’s hands: his company has a 2050 net zero target and is committed to structurally decreasing oil & gas output by 40%, but it owns 20% of Rosneft which is trying to up its output bigly with Vostok Oil. Looney is openly talking about peak oil demand. Igor Sechin doesn’t seem to understand macroeconomic reality that even if it hasn’t arrived yet, it’s coming soon. Rosneft accounts for roughly 1/3 of BP’s output at this point, and provided $785 million in dividends and $2.3 billion in pre-tax earnings for BP in 2019. On a normal market, that’d be a big financial draw. Oil prices in 2019 averaged $64 a barrel and investment into new oil & gas production was, very slowly, rising after its 2016 nadir:

Upstream investment took a massive hit in 2020, and while Sechin could be forgiven for betting big on a price recovery driven by under-investment, lower levels of absolute investment are now necessary to sustain production compared to 2014 because of the steps the industry took to cut costs. In other words, this net decline in investment doesn’t necessarily indicate a massive production decline in waiting that will reward national oil companies, though it is certainly the case that NOCs have more relative power on a declining market given they can plan for investment horizons differently and there’s a delay of several years to realize the effects of depressed upstream investment levels. The current price stabilization has put an effective floor on decline, however, and I’d expect we see some return towards ‘normality’ in 2021 with any withheld investments a reflection of demand uncertainty and not an inability to profit at current price levels or in the medium-term. In other words, NOCs will have to grab market share quickly if they want to avoid rising private investment levels as oil majors make way for mid-sized firms, less diversified firms to pick up the slack.

The reality is that BP stands to benefit most holding onto its Rosneft equity until oil prices reach another peak in the near future. Earning $3 billion from the business isn’t really wort that much for its longer-term plan of financing its green investments with more profitable oil & gas projects. Rosneft’s future earnings growth is basically a result of tax breaks and state support for its brownfield projects and for Vostok Oil, not a result of improved corporate management. Further, the tax burden on the company has been raised by MinFin as it tries to top up the budget during a new round of fiscal consolidation that can’t be unwound without either a sustained significant increase in oil prices or higher levels of growth for Russia’s non-extractive sectors. And that’s also not factoring in that whatever greenwashing efforts Rosneft takes, investors will not believe it credibly is moving to reduce its carbon emissions with a figure like Sechin running the show until the company makes significant, and in that case shocking, progress doing so. As it stands, BP’s equity stake is worth in the realm of $17-18 billion. LHS is each shareholder’s % share and RHS is equity value in US$ blns:

Per the reportage, BP has every intention of remaining strategic partners with Rosneft and hasn't included the company’s reserves in its net zero targets. The question is how long investors are willing to accept that. BP’s acquisition of majority control of Finite Carbon, a US-based carbon offset business focused on reforesting, in December was a good initial step to offset existing emissions and buy it time to pivot. Finite Carbon is a web platform that enables small landowners to access carbon offset markets, thus netting them more revenue. The company claims to have helped landowners earn $500 million in revenues for 2020. That’s nothing like what upstream assets in Russia generate, but there is far more room for business growth — and future M&A — for BP in that type of business. The real longer-term play, however, lies with serving the tech sector. BP’s deal with Amazon to provide renewable energy for its aggressive net zero targets while in return receiving help digitizing its operations, thereby lowering operational costs, is the sort of thing that won’t provide annual revenues in line with what Rosneft can generate, but again, offers a much better growth outlook as a business. Rosneft’s output may not even increase much on net with Vostok Oil given it’s now trying to sell off older or else smaller assets where feasible — look at Equinor’s acquisition of 49% of an onshore subsidiary in Eastern Siberia — which suggests that in actuality, its not its profitability that makes it a strong investment draw. Rather if it can reduce its debt load further, it can pass on more in dividends. Doing so, however, is not usually Sechin’s style when a big project is in play and would require yet more support from the state. Recall the following from the 2017 Sber(bank) report authored by Alex Fak that was retracted because of its criticisms of Rosneft’s inefficiency:

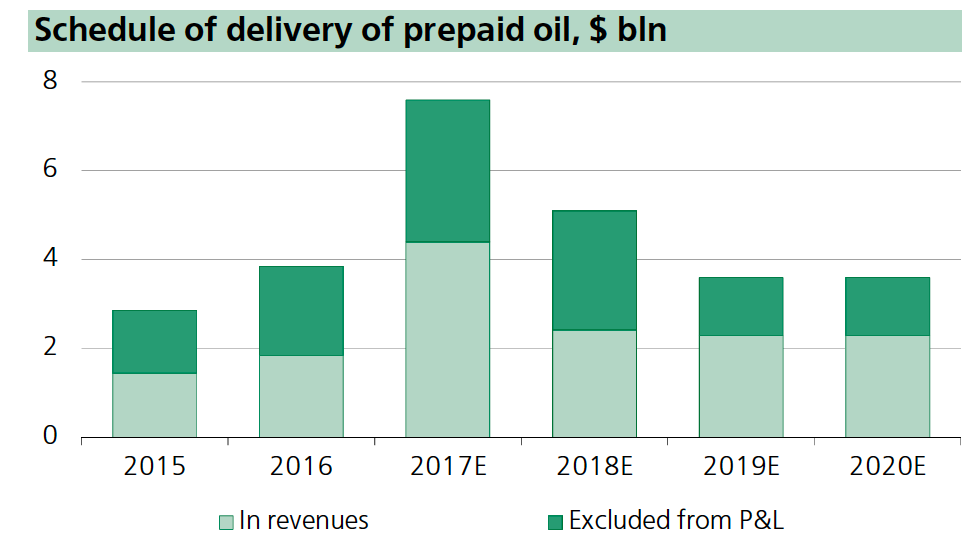

Rosneft’s brownfield costs have been rising for years and as of several years ago, they accounted for over 60% of the company’s production base. For this reason, the company has obsessively fought for greater tax breaks for its core brownfields like Samotlor. Add to that the firm’s billions of dollars of revenues earned via ‘prepayments’ for volumes of oil that Rosneft guaranteed after acquiring TNK-BP and other assets — in past years, some of BP’s earnings from Rosneft were effectively money it had given the company being recycled for these volumes — and that Rosneft often adopts contracts on these grounds to finance upstream investment when closing newer supply contracts such as those deals reached with CEFC China Energy, it becomes clearer that while BP may earnestly have no desire to divest from Rosneft at the moment, the biggest impediment is the lack of a buyer and a bet that an increase in the oil price would improve the company’s balance sheets by giving it greater equity return it could, when ready, try to sell in order to realize lower, but more stable returns deploying said capital into other types of energy and affiliated investments. Rosneft is not necessarily going to be increasing its net output significantly depending on how it pursues its stated brownfield divestment strategy and it’s not an attractive partner in a persistent low oil price environment either.

From Rosneft’s perspective, I highly doubt there’s any short-term fear of BP trying to move its equity stake. However, if it does so should BP change its mind depending on how the market recovery and the realized yields from green investments, the only serious contenders to buy its stake are state-backed institutional investors from the Gulf or a domestic sale since Chinese investors don’t trust Russia and Sechin, Japanese investors don’t either, India might entertain it but doing so would draw fury from Washington, and other international, private oil firms wouldn’t touch it for risk of sanction or else lack of profitability. Doing so would raise significant capital for Vostok Oil and give Rosneft’s board more breathing room to ignore the growing pressure on BP to fully commit to its newer, greener strategy. But that would also more deeply enmesh Rosneft — and Russia — into Gulf politics and OPEC+ production cut arrangements. Foreign policy and economic policy have become inseparable because of Russia’s dramatic failure to escape the effect of the oil price on the country’s business cycle and on cross-subsidization for other sectors, never mind the fairytale that reduced oil & gas tax revenue dependence signals true diversification. And the case of BP’s stake in Rosneft will be a fascinating pressure point in years to come as the energy transition picks up speed.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).