Top of the Pops

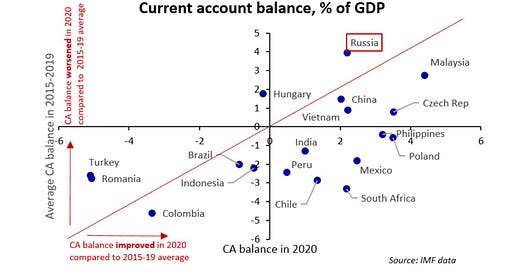

Now that oil prices have (largely) stabilized, it’s worth noting that Russia’s macro experience during the worst of the crisis last year was actually exceptional compared to most emerging markets. Whereas many saw their current account balances improved due to the collapse in energy prices and currency valuations, Russia’s took a hefty hit:

Now that US-Iran negotiations are trying to make headway within the prescribed bounds of what’s domestically possible for both countries, Iran is signaling that it could return to exporting 2.5 million barrels of oil per day with the lifting of sanctions. Exports took a huge hit after May 2018, but the official data understates continued export levels given Iranian production has increased without a significant change in domestic consumption (from what I’ve seen, at least). The prospect of diplomatic progress should be a concern for Russia’s current account going forward. If some sort of agreement were reached, the ongoing rising Iranian supply would also increase the salience of Russia’s domestic oil investment challenge. The security implications of the JCPOA trump the economic ones for Moscow. But they can’t be ignored. Jan.-April oil exports were still down 20.5% by volume year-on-year and the easing of cuts will make it very difficult for Moscow to impose production discipline on the oil sector again in case of a future price collapse, something to worry about the longer that developing countries struggle to access, produce, and distribute vaccines.

What’s going on?

The news slowdown from the paid holiday from May 1 to May 10 has ground the news flow to a halt, but I caught a great writeup in response to Putin’s renewed regional gasification promises from his federal address that’s just now being turned into executive orders. To my ear (and Vladislav Inozemtsev’s apparently), the gasification promise seemed like a bizarre throwback to the 2007 Eastern Gas Program and earlier attempts to use Gazprom as a development driver. The order makes it much clearer what’s going on. Putins’ directive is intended to get Gazprom to link up homes that aren’t connected yet for free through 2023, effectively replacing growth and rising incomes with the promise of building stuff for free. Since Gazprom’s profits last year collapsed 88.7% last year, it’s hard to imagine the new promise is welcome in the boardroom. As usual, the reiterated order to gasify more of the country left out the hardest part — who pays for the actual local distribution and end-use gear/infrastructure at the “last mile?” No funding source has been announced and the implementation has fallen to Mishustin, but the piece linked from Neftegaz cites 350 billion rubles ($4.65 billion) for the total cost. Regional governments are likely going to have to eat it in the end while Mishustin figures out some sort of compromise on costing and pay-for, especially if this approach is taken for other social initiatives in an attempt to kick costs onto SOEs who’ll only be able to recoup costs through fees and use charges down the road.

This is from a few days back on Kommersant, but the paper paints a damning picture of what’s happening to the average consumer in Russia when it comes to food. Aside from bread (and sugar of course), the average Russian is falling behind MinZdrav nutritional recommendations. To be fair, this happens in the US and plenty of developed countries too, particularly those with higher levels of inequality, but what’s so stark is that that Russian authorities have slowly reintroduced measurements for public and economic health that mirror their Soviet antecedents, citing specific kilogram amounts for basic goods as a measure of policy success or failure:

Title: consumption basket compared to recs for rational nutrition

Descending: bread (and bread products), potatoes, vegetables/melons, fresh fruit, sugar and sweets, meat products, fish products, milk and dairy products, eggs

Green is the actual amount of kg and blue the recommended amount. Authorities are failing even by their Neo-Soviet “economic security” metrics slowly introduced after the annexation of Crimea. The average consumer in Kazakhstan eats better than the average consumer in Russia. These are alarming figures given that incomes are still falling, and should put paid to any notion that the economy is in recovery. Any observed recovery reflects 3 factors — budget spending pushed up into 1Q, higher export prices, and rents accumulating to large(r) firms or else firms with pandemic-proofed demand and state support.

The positive momentum seen from the March IHS Markit industrial PMI — it came in tepid at 51.1 — eased back in April to a 50.4 reading. Cost rises passed onto clients and consumers are at their highest since February 2015. Businesses are the most confident they’ve been since January 2020, though. That counts for something. Just not very much given how atrocious the pre-crisis trends in the economy were since the economy slowed in the second half of 2019. Bank profits ticked up 9% for 1Q, but that’s down to lending expansion. The question is how much of that expansion is debt to keep people living like they were before COVID struck and how much of that is actually correlated to growth. Declining real incomes would imply that industrial recovery would likelier benefit exports than domestic consumption since inflation is a huge problem for Russian consumers. Pochta Bank is a good example — they offered repayment holidays and asked for nothing from borrowers for 6 months+ and as of now, 35-40% of those who took advantage haven’t been able to return to their prior payment schedule. A record 67% of new builds under construction in Moscow are using escrow to hold funds with a third party until the project is completed. For every sign of improved business confidence, there’s evidence of higher borrowing levels, declining creditworthiness, and concern about making sure about payment schedules and reducing upfront risk. What seems likelier to me is that the demand boost from moving up budget spending — 33% of the federal budget was spent in 1Q — is subsiding without much else helping out.

From the end of April, RBK ran a piece on the optimization of state organs and improving incentives for state officials. What’s striking is the gap between the median wage nationally and decision-makers on the government payroll and how the lack of real income growth and high-quality jobs created in the private sector or else at the lower end of a lot of SOEs cultivates an environment where anyone wanting to get ahead is really stuck shooting for a state job. Forgive the lack of clarity as English poorly renders the distinction administratively in some cases:

Green = deputy minister Blue = department director Black = manager/head Red = branch/department head Grey = Deputy branch/department head

These are all measured against the median — around 35-36,000 rubles a month. As we can see, state managers are now collecting the rents of neoliberal statism after a brief post-Crimea downward revision during the worst of the budget consolidation and revision initiated by MinFin. There’s also something to be said for turnover and the need to incentivize performance. The more pressure is heaped on managers to deliver outcomes, the more reason to pay them more. The more you pay staffs, though, the greater the appearance of graft or else opportunity to leverage these positions into personal gain because of the central role that departments play in shaping the distribution of rents. Internal proposals to increase the relative size of staffs and better define roles and policy responsibilities are a never-ending process of promising improvements while creating grounds for a new wave of policy entrepreneurs who carve up each other’s respective fiefdoms. Emptying the system of political animals and replacing them with technocrats only works if you have a firm grip on the balance of interest groups at the top of agencies, SOEs, and major private sector firms. That’s lacking. What’s likelier is that you’d see nominal efficiency improvements for services, especially anything that entails face time with Russians locally, with any decline in the size of the state labor force offset by state-owned entities hiring more or else taking on more political responsibilities if optimization efforts fall short.

COVID Status Report

Russia recorded its lowest daily case count since September — just 7,770 new cases and 337 deaths reported. The Operational Staff paints a positive picture, one that presumably is being boosted by the May 1-10 holiday period intended to act as a ‘circuit breaker’ on any rise in cases. There’s a huge problem with the data, however, one that reinforces my suspicion running back to December that once the vaccination campaign started, the topline data would be cooked to the extent possible: March excess mortality data was up 25.6% year-on-year and 26.9% more people died in 1Q this year than last year. It’s the worst spike in mortality since the 1947 post-war famine in the Soviet Union — the mortality increase was over 37% in annualized terms for that year. The January increase numbers were up 33%, though that seems to have come slightly closer to trend since after 2020 data showed an 18% increase. The longer the current trend lasts, the likelier that 2021 will prove deadlier than 2020 in Russia. Excess deaths on this scale are not just a social, public health, and political catastrophe, they can move macroeconomic data. It’s exceedingly difficult to be optimistic about recovery though the daily vaccination rate is just high enough to have an impact in time. But what happens when demand craters because half the public doesn’t want one? I don’t know. All I do know is that using reopening metrics like foot traffic to imply things are getting better is absurd in the face of accumulating evidence,

How not to analyze the Russian economy

So I saw this data crunch put out by bne intellinews covering the state of the Russian economy, and while there’s a lot of data and facts in here well worth scrutinizing and it’s a useful reference point, it’s a piece of analysis that calls to mind just about every conceivable mistake one can make assessing the strength of recovery in the Russian economy. The issue isn’t being ‘wrong.’ Ask an analyst about the Russian economy and it’s a Rorschach test, so I accept that I probably have a bleaker intuitive position than many out there. There’s latitude for disagreement. The problems here are methodological and ideological, and they permeate debates far removed from the arcana of Russian economic policy as well. From the get-go, it dishes out the old “Kremlin’s playing it safe and steady” line, which is strictly true, but accepts a false premise. Investment and spending in the economy create productive capacity and resources as cash flows rise. The conservatism warranted in 2014-2015 during the initial explosion of capital outflows made little sense by H2 2016. COVID proved the state could borrow a large % of GDP using state banks to finance expenditure. To couch analysis this way is to accept the rentierist logic of Russian macroeconomic policy based on its approach domestically and to foreign policy without scrutinizing what is actually possible or what good performance looks like, akin to saying Trump’s economy was great because of topline data without digging into the massive amount of slack on the labor market or unused capacity across the economy. Let’s start with the first major claim the piece makes:

“Still, compared to most other countries Russia is doing very well, partly because thanks to those same geopolitical tensions it went into the coronacrisis crisis so much better prepared than most other countries.”

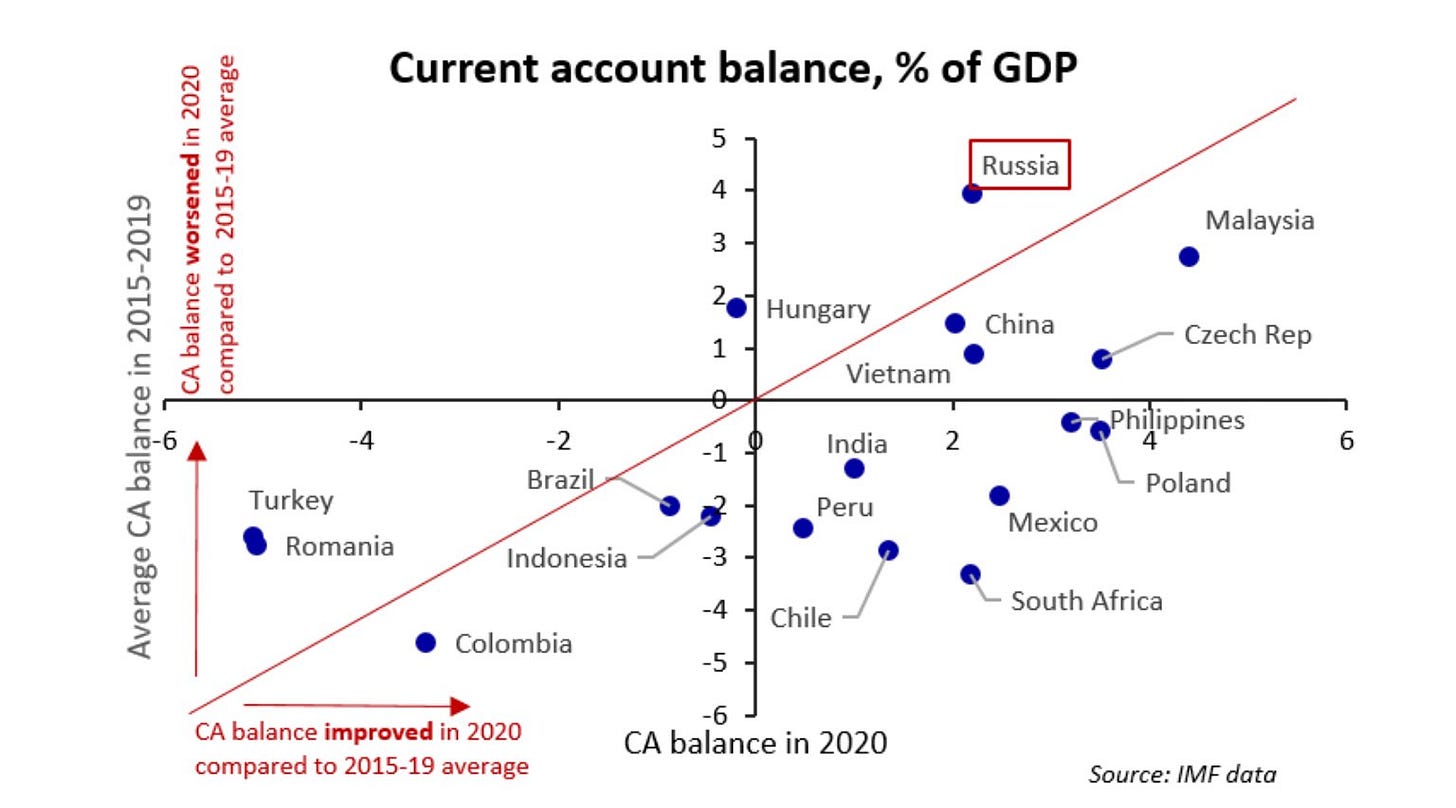

This is analytical malpractice. Russia’s recovery has been export led thanks to the rise in global commodity prices. Put simply, external demand allowed Russia to “ride out” the worst of the crisis, and the systemic mismanagement of the economy and huge amount of slack across most sectors limited the downside impact because of the steady contraction of household spending power. Consider the breakdown of corporate turnover in current ruble price terms since January 2020 against the overall price level for commodities. LHS is blns rubles:

The commodity index includes both fuel non-fuel commodities + gold. Since Russia’s consumer economy is fairly weak, this recovery is basically a commodity story with a small degree of fiscal stimulus, primarily doled out via support to businesses to maintain jobs. Further, the massive drop from December to January is linked to the traditional spurt of retail spending around Christmas and backloaded budget spending for 4Q. The ‘recovery’ was backstopped by a drawdown on savings and the spike in March retail corresponded to a record high volume of consumer loan issuances — 340 billion rubbles ($4.5 billion) amid rising inflation and rising real rates as the Central Bank began to tighten monetary policy. Apparently calls with the analysts at investment banks and economic analysis practices yield answers like “well, the worst is over and the economy is recovering way more rapidly than expected.” Why is that? Ask an investment banker and they’ll tell you things are looking up. They’ve got action to trade on, equities have stabilized or returned to growth, and there’s appetite for risk. But investment bankers and, to be blunt, the analytical consensus around Russia as a relatively impervious economy are predicated on a faulty narrative of Russia’s macroeconomic stability. That ‘stability’ is reflective of the near constant demand destruction incurred by fiscal and monetary policy approaches, and therefore follows from dynamic factors that, even beyond the geopolitical risk premiums you see for ruble valuations or OFZ purchases, are anything but stable. Ask a schoolteacher in Volgograd trying to cover groceries for her son and medical care costs for her mother and stability is a myth. Even the macro figures bely a system accumulating stress points.

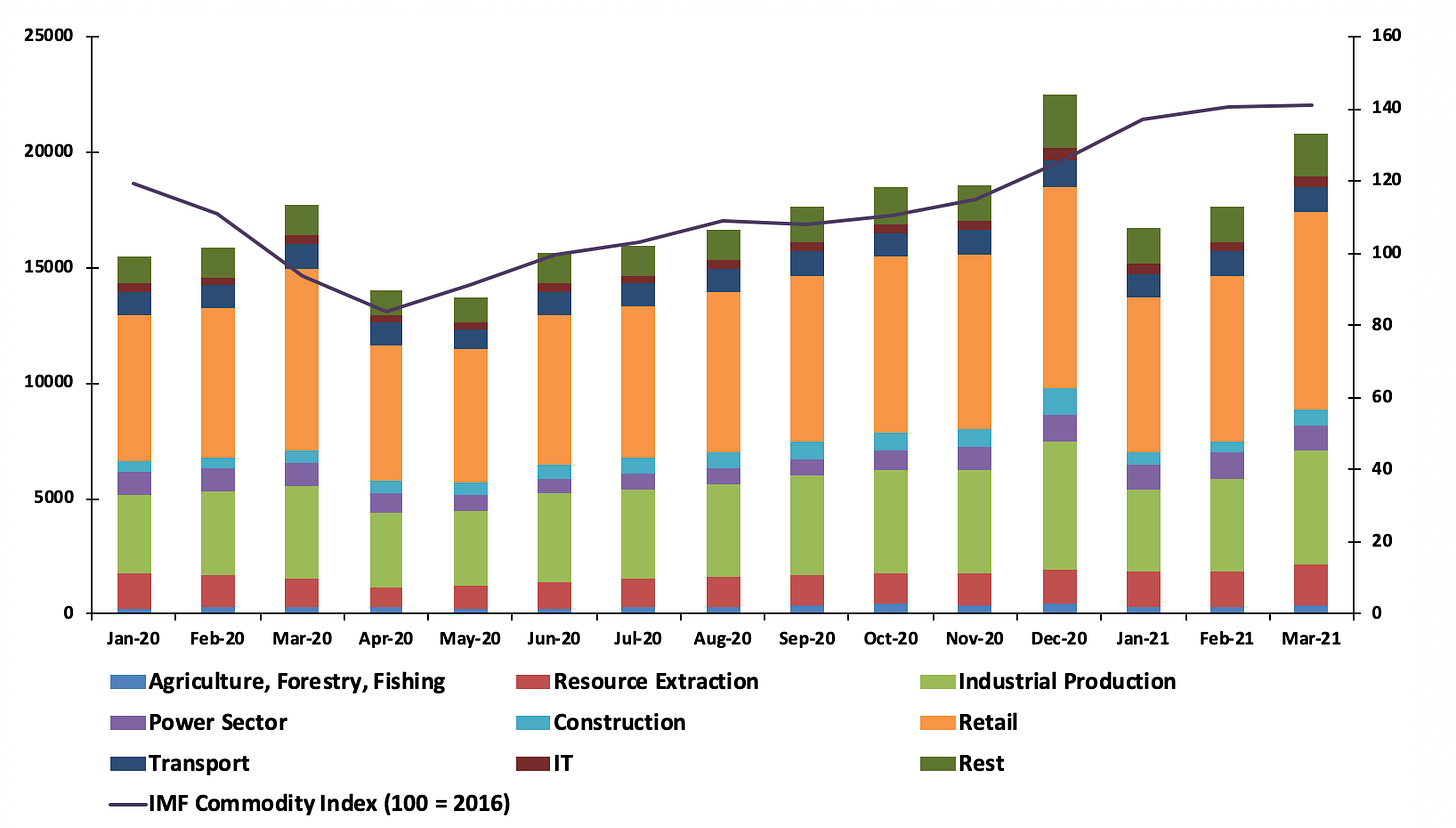

The piece also asserts some sort of growth momentum without any significant evidence to that effect. If GDP increases reflect the relative price differential for resource/food exports without any significant change in domestic investment levels for business or rising consumption levels, it’s not offering much “growth momentum.” Industrial production is a crucial metric, but a messy one to use to justify emerging growth momentum, particularly since it’s cyclically linked to budget spending:

A 1.1% year-on-year rise against a month that saw a 10% decline is not evidence the tide’s turned decisively. It’s not just a low-base effect that’s the issue. The inflation crisis — something pointed to towards the end of the research note — is linked to GDP growth and producer problems. The rise in commodity prices normally benefits Russia since oil traditionally leads the way, but that’s not the case this cycle. So instead of more oil rents to redistribute, food prices and physical inputs for construction and industrial production are rising in price. Use an everyday example. Milk production costs rose 18.2% between March 2020 and March 2021. It is true, however, that demand for output and services are recovering against their lows from last year, which has put more stress on the labor market:

The unemployment data doesn’t speak to the actual quality of the jobs left or created, the feedback loop between migration-related labor shortages and firms’ operating costs, or the likely higher degree of informality for employment triggered by business losses. The “recovery” narrative also understates the scale of the damage for SMEs. Between 2015 and July 1 2020, the National Guarantee System intended to provide cheap credit to SMEs reached less than 1% of all firms, and that failure accumulates damage over time. Last year’s measures kept plenty of small businesses alive, but if they’re reopening to an economy with an even lower share of consumption vs. export production, countless firms will go under during the period of “normalization.” Using budgetary balance as a proxy for improving economic health is, frankly, comical. A budget surplus in an economy with this much slack and weak demand just forces households to borrow more and drives down their own consumption power, especially as tighter monetary policy from the Central Bank increases the cost of credit on top of the effect rising inflation is having on deposit rates, loans, everything really. Corporate profits may appear to be the best in 5 years nominally, but if they are in real terms, then what’s really happening is that companies face a market without adequate demand to spur investment — even the export sectors face constraints, whether they be political in the case of oil or from uncertainty such as the metallurgical sector and mining since the former now wants the state to impose price control measures on the latter, which is just waiting for Moscow to increase the tax take on the metals that’ll fuel the energy transition.

The problem of analysis in the vein of this writeup is that it takes a host of assumptions about Russian macro as a given. There’s no questioning of the efficacy of fiscal policy, an implicit assumption that higher debt levels leads to inflation, and an oddly undeveloped understanding of the way that global markets affect Russia given its lopsided integration. ‘Good’ gets rounded down and down and down until it ceases to be analytically useful. Biden’s stimulus package and now Europe’s improving vaccination rates are likely to sustain commodity price inflation, which Russian firms can’t manage as well as foreign MNCs because they source more of their raw inputs domestically, face currency risks for imports invoiced in Euros/dollars/yuan, and have a weak domestic market to begin with. Russia tends to generate an analytical incentive to be contrarian. This take is itself an example of that problem. But when contrarian takes isolate nominal measures to draw conclusions, assume all imports are invoiced in USD, or else fail to distinguish between Russia’s export growth or recovery and broader domestic growth — export growth hasn’t really driven broadly-based growth since 2012 — they aren’t usefully capturing the risks that economic mismanagement pose. What’s even weirder is leaving out the fact that any surplus export earnings are likely to be recycled into import substitution programs run by SOEs that then increase costs for end-use consumers and affect the pricing power of domestic buyers since SOEs and parastatals compete with larger private producers and SMEs for resource inputs and industrial production. Inflation is a self-sustaining dynamic from macro and industrial policy, not just commodity prices.

There’s not 2020 data included yet, but when you look at Russians’ average savings rates and compare that to the % firms that are loss-making, it’s state policy filling the gap for firms. Cheap credits, guaranteed demand via regulatory rents, and so on. When it comes to households, there’s been very, very little. Without them, investment recovery will cluster in export sectors, then likely to intensify inflationary pressures since those sectors are most prone to price control intervention. Russia wasn’t more prepared for COVID. It just hobbled itself in a convenient manner for a service-demand shock. It’s still hobbling its recovery. Good is exceedingly relative.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).