Top of the Pops

A quick heads up that Monday will be a Eurasia day.

Cue up your Ron Paul gifs cause the market for refined products has finally hit a tipping point many market participants have been waiting for. Chinese refiners refined more products than American ones for the first time over the course of 2020:

To be sure, it’s obvious that there was a huge drop-off in demand due to the United States’ terrible handling of the pandemic and we’d expect the US figures to rise back towards 18 million barrels per day if not higher thanks to the Biden stimulus plan and vaccine rollout. Plus the expected infrastructure plan, if it goes through, calls for massive roadworks that would sustain higher levels of bitumen and other heavy oil product demand in the near to medium-term. As I noted back in the fall, China’s overtaken the EU in terms of refining capacity and while it still has a way to go to fully catchup to the US, we’re reaching that point where the shape of the demand recovery may accelerate it (if it affects US refining margins based on Biden administration policies):

In practice, China’s the refining market Russian refiners looking to export have to worry most about. Europe’s refineries have struggled with terrible demand and margins accelerating a long-term culling of capacity on the continent made redundant by greening policies, good public and regional transport systems, and product import pressures from rising Middle East products capacity as well from the US and incoming pressure from West Africa — Nigeria’s historically imported products from Europe but the Dangote refinery will shift these flows considerably. The result is that Russia still has a decent outlook to dump heavier products like bitumen (used for road construction) because of the long-term fall in European capacity. China, however, faces an imminent supply glut if it keeps authorizing large refinery projects and its consumer-driven demand doesn’t grow more quickly. Excess production will inevitably harm profit margins for refineries in Siberia and the Far East unless they’re more complex and specialized as is the case with the Amur Gas Processing Plant, not a strong suit for Russia’s downstream oil sector with the domestic demand outlook so weak.

What’s going on?

The government’s ready to take the next step refining personal data collection efforts from social media and other sources by triggering an automatic transfer of said data to the Unified Government System (EIS). The EIS is the de facto ‘database’ for a wide range of state activity, and the thinking is that when consumer agrees to the terms and conditions of any given platform, they can choose whether or not to hand the state the power to identify them or collect their data from that platform. As of now, the registration system for data in place with the EIS builds off a December legal fix requiring that companies seek legal permission to collect data in the first place while the EIS makes use of user’s existing passport data gathered in the “Gosuslugi” portal with a now amended identification and authorization system linking one’s online data with their passport details. What’s interesting is that these proposals really aren’t about surveillance at all. Rather they’re trying to ensure consumer rights to know what they’ve agreed to and allow them to change the terms of their use, a crucial legal component for market competition between e-service and online platform providers that the state clearly wants to foster to the benefit of domestic firms using other barriers such as the attempted ‘Twitter slowdown’ to push users towards Russian counterparts. Concerns about the state unilaterally collection data are obviously still warranted — the problem Russia’s historically had was one of both physical/technical and institutional capacity. Ironically, clarifying rules makes it easier to find workarounds, better build out capacity, or later on pass a more stringent regulation. All three benefit Mishustin’s crisis center.

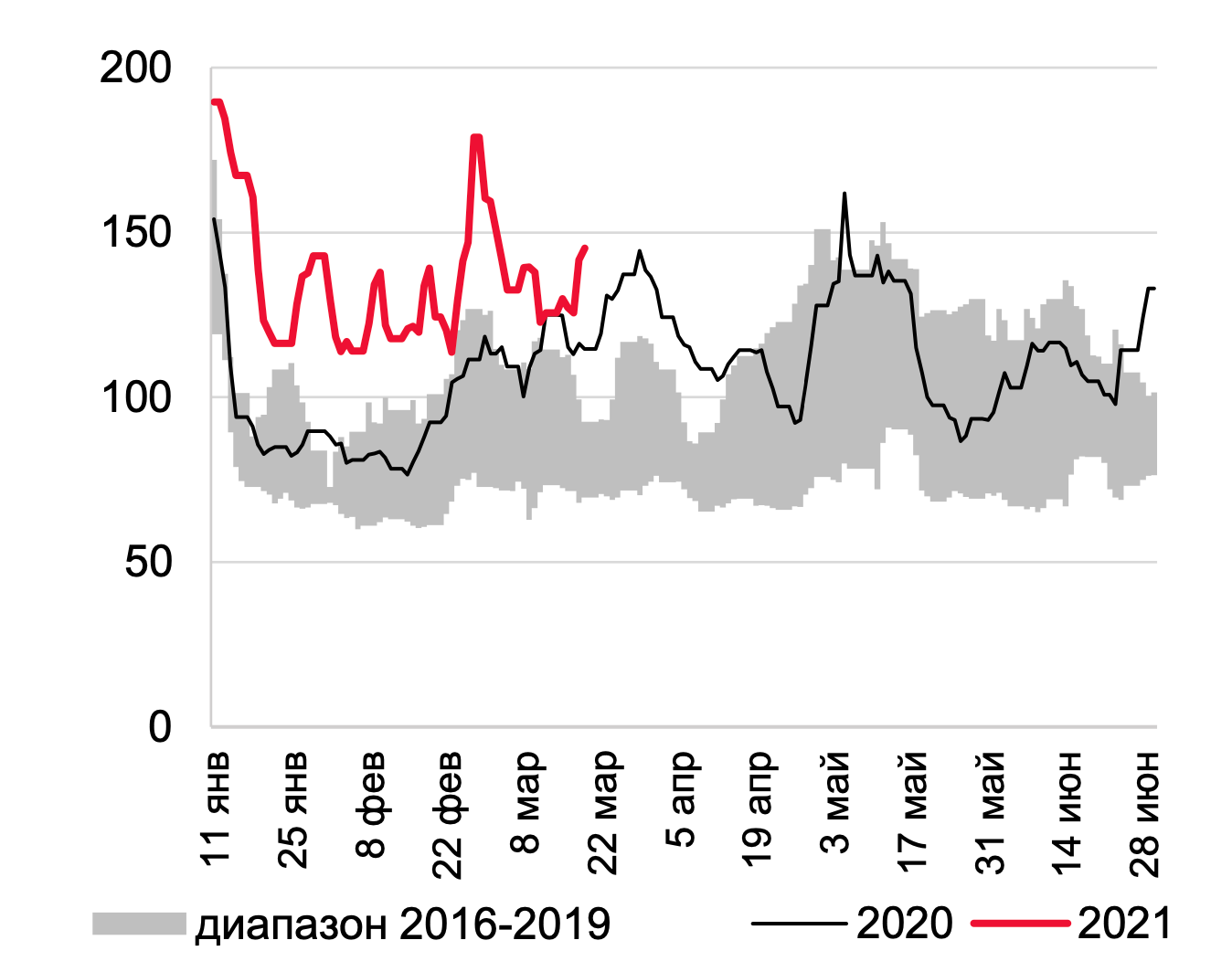

Despite the late February assurances that inflationary pressures would peak by mid to late March, Russians’ inflation expectation ticked back up again after falling for Jan.-Feb. despite rising observed inflation. The observed inflation rate for February hit 12.3% — a 4-year high and huge cause for concern based on the shift in the expectations trend. The moment’s bound to prove a real challenge for the Bank of Russia’s ability to use monetary policy to ward off worse price increases:

Gold = annual inflation Red = observed inflation Blue = inflation expectations

The number of people saving money has reported dipped slightly since the start of the year, but that seems more to be for want of income that can be saved since surveys shows the mood of consumers has worsened. The giveaway is that less than 30% of people are holding said savings in bank deposits as of March, evidence that people want cash in hand, no wait to use it, and are planning for worst case scenarios. You’d expect that figure to as high or higher than it was as of last March since the crisis in Russia started then. The continued rise in prices is widely seen as a guarantee of another rate hike from the CBR in April. It’s now a race to figure out when the hikes hit the cost of credit and consumer demand.

Business experts polled by Vedomosti agree that the biggest drivers for commercial transport equipment/machinery demand this year are e-commerce and delivery services, the digitalization of sales, and the development of subscription and rental markets. As is probably clear to you, these three trends suggest that there’s no consumer push this year coming. E-commerce income tends to come at the expense of brick & mortar retail incomes, and therefore may well end up hurting the greatest single source of job creation in the Russian economy since 2014-2015 — low wage brick & mortar retail work. It’s still expected that sales for tractors, light automobiles, and buses will recover this year, despite uncertainty about recycling requirements that would significantly raise costs, but the market for vehicles is likely to stay at its 2020 level. Continued income decline for consumers, however, may put a dent in these hopes. The piece offers more color worth a peruse if you’re interested, but my own takeaway is structural: some of the biggest drivers of intermediate demand between sectors in the Russian economy come from the developments in e-commerce and digitalization that would provide productivity/efficiency gains and more consumer choice in a growing economy, but have differentiated effects on a stagnant market where labor productivity is actively constrained by state policy despite claiming otherwise in order to maintain high levels of employment while also costing companies profits that could otherwise be invested.

Rosneft has taken out a lawsuit against VTimes journalist Alina Fadeeva for covering a story that emerged from the company’s own reporting — Rosneft likes to understate the value of the assets it buys, clearly skewing the amount of money spent, profits realized, and transferring wealth to itself using its political muscle. In this particular instance, the problem came from the $11 billion purchase of shares, assets, and access to the Taimyr fields owned by Rosneft ex-president Eduard Khudainatov. But independent audits from the Big Four auditing firms estimated the deal should have been valued at $30-40 billion based on the assets involved. Rosneft had effectively ‘gifted’ itself $20-30 billion it didn’t have to borrow or else spend by dodging competitive market rates for the transaction, realizing much greater profits down the line. Fadeeva’s reference to what was openly available and completely normal license to use an attention-grabbing headline is now being litigated as an attack on the firm’s business reputation in a suit everyone acknowledges Fadeeva would almost certainly win were it not for Rosneft being the plaintiff. Essentially, Rosneft now has to prove in court that the deal was advantageous in business terms for Khudainatov and his company despite the clear evidence from third-party review that it wasn’t. On the one hand, this is classic Sechin Inc. They file absurd lawsuits denying facts that even counterparties have publicly acknowledged if a piece doesn’t sit right with them. On the other, I think it’s also indicative of the political effect of diminished equity valuation expectations for oil & gas fields as well as future profits from their operation. These deals were already taking place pre-2014-2015, but since the oil price environment has by all appearances permanently shifted downwards, especially with the collapse of marginal demand increases and potential for near-term permanent decline to set in, Rosneft’s got more reason than ever to disguise its own mismanagement and economically illogical business strategy by artificially ratcheting up investor returns through these maneuvers, boosting stock prices and also making BP and the Qataris happy.

COVID Status Report

9,167 new cases reported against 405 deaths. The only real ‘news’ on COVID proper to note today is the Duma’s reaction to France’s rejection of Sputnik-V and its own struggles to manufacture enough doses. Continued interest from Germany to push through purchases of Sputnik V since they’re desperate to cover for their domestic screwups. Boilerplate stuff. But some a new Levada survey on Russian perceptions of their quality of life i.e. how much you have to earn to make a living wage offer are damning for the regime and the recovery ahead. The number of Russians who think they earn more than a living wage has fallen from its 2014 high of 38% to 25%:

What’s more, the gap between respondents’ perceptions and the official figure from Rosstat have grown substantially further apart, which implies either a higher rate of inflation than that published statistically, rising costs of living from various sources not captured in the statistics, and Russians’ persistent fears of price increases that reliably outstrip measured price inflation no matter the context. Dark blue is what’s perceived, light blue is the average family income, and grey is the official living wage/income:

The above covers one person, I’m assuming the family stat refers to average earnings per person within a family but it’s a little unclear from my quick read this morning. Back in 2014, the average family earned close to what was perceived to be a decent, living wage/income. There’s now a huge gap. This chart probably does more than any other to capture the evolution of protest activity, falling turnout, and other political challenges for the regime. Without greater income transfers of some kind if there isn’t greater growth, I’ve got no idea how the Kremlin can arrest this trend, especially if official data isn’t well capturing what people perceive is happening in the economy.

DebtCon 1

According to Central Bank data, Russians were spending an historic high of 11.7% of their income to service debts held as consumer debts and mortgages per the methodology. The breakdown between the two was calculated as 9.8% for consumer debts and 1.9% for mortgages, the latter clearly being held down by the subsidy program given the large mortgage lending surge from 3-4Q last year. Curious for a gut check comparison, I pulled some CBR data from which I could derive a sense of how much these debt service payments are worth:

Household debts were above 20 trillion rubles ($262.8 billion) coming into 2021 and, though less discernible here because of the scale, households’ share of non-financial sector debt has inched upwards since the start of 2019. Implicitly, this means that households are borrowing marginally more than businesses, presumably to maintain consumption and standards of living. It’s another indicator that points to a worsening consumer demand outlook since businesses have less reason to invest unless they can realize export growth. The last quarter of labor’s share of national income using a GDP proxy was just a guess on my part, but it seems to be reasonably within that range. Then using labor share of GDP against the 2020 GDP value release in current prices from Rosstat — setting aside that income can be derived from financial or fixed assets that don’t constitute wage earnings the measure is focused on — I then applied the income % the CBR reported households were spending to service debts to arrive at two respective figures to give an idea of the scale of the problem: the figure cited amounts to somewhere around 5.5 trillion rubles ($72.21 billion) of servicing payments worth a bit over estimated 5.1% of GDP. That’s with persistently high savings rates at the same time, which underscores just how bad the consumer recovery appears to be as well as the expectation that Russians would have to save more in relative terms as credit costs rise from a more aggressive CBR rate hike strategy.

For brief, inartful comparison, Russian households are now paying more of their earnings in % terms than American households have since 2010-2011 when they had just deleveraged from the worst of the 2008-2009 financial crisis and household borrowing expansion in the US from 1994-2008 that began during what was otherwise supposed to be a boom period. It’s not helpful to compare apples to oranges, but it emphasizes that household indebtedness in advanced economies may have occurred during periods of wage stagnation, but not broad price inflation (aside from healthcare, education, and housing) or real income decline. This dynamic recalls the implicitly monetarist rendering of threats to Russia’s economic security noted in the 2017 doctrine Putin signed off on. It’s a small bit, but I think says volumes about the misguided thinking and contradictions of the political leadership’s grasp of issues like domestic household indebtedness. The following is a bullet point example of a challenge for Russian economic security:

2) усиление структурных дисбалансов в мировой экономике и финансовой системе, рост частной и суверенной задолженности, увеличение разрыва между стоимостной оценкой реальных активов и производных ценных бумаг;

Moscow notes worsening global imbalances in the world economy and financial system, the rise of private and sovereign indebtedness, and the increasing gap between the value of real assets and securities. None of these make any sense within the multipolar foreign policy framework or the domestic economic policy framework when you unpack the implications here. First off, some kind of condominium between the US, EU, and China that would reduce the dollar’s dominance in global finance as well as a shift away from consumption suppression and export-led macroeconomic policymaking in the EU and China would be needed to correct global imbalances. Russia actively pushing the US and EU together politically without offering any meaningful economic counterweight within Eurasia makes that impossible even if there was some mutual interest in Washington and Beijing. Second, the rise of household indebtedness in Russia corresponds rather directly to the state’s decreased level of indebtedness and refusal to run budget deficits unless in an emergency. Given labor has a large share of the national income but the national income is heavily dependent on state spending and state banks leading targeted credit expansions as needed for political ends, budget surpluses generate household deficits so long as there is no strong external or internal growth driver for the Russian economy. There hasn’t been for 8 years and import substitution efforts merely swap consumption with less efficient, more expensive consumption in most cases (at least for now). That’s an imbalance that comes from their approach and fears that monetary expansion always creates significant inflation. Finally, the gap between the value of real assets and securities is a reflection of the disinflation in advanced economies exacerbated by the right-wing ideological priors that Russia’s own security document seems to maintain, if with a Russian accent. When growth is weak for wages and GDP-correlated industries and inflation is low, companies that promise future cash flows don’t face any significant ‘discounting’ effect if someone bets on that growth i.e. future potential cash flows aren’t devalued very much by inflation if you buy today. They can effectively monopolize the growth story on the financial market, even if they aren’t actually doing much of productive value, and draw in more capital hunting for yield. The constant fear in Russia is clearly that some combination of financial illiteracy, private profligacy, and the excesses of financialization will lead to ruin, and because the default macroeconomic policy is deflation, that invites private sector debt to make up the slack of falling incomes from said economic deflation amid continued price increases.

So what’s the Central Bank’s response to an emerging household indebtedness crisis if real incomes fall any further? It’s lobbied the Duma to introduce new legislation that would further tighten regulatory oversight over bank loans that aren’t secured by any collateral. It would give itself the right to unilaterally set the amount of consumer credit banks can extend. This is a continuation of increasingly obvious attempts to build out flexible planning capabilities for the financial sector with the intention of fighting instability. In effect, the Central Bank will impose % quotas on how much credit with a high probability of default can be issued, allowing credit to flow but inevitably decreasing households’ access to credit. The Central Bank and Kremlin remain hostage to the belief that monetary policy is the means by which these domestic imbalances can be fixed instead of fiscal policy. Take the case of food production. The following is the relative level of capital inflows into the sector monitored by the CBR:

The good news is that higher prices are leading to much higher inflows for production, which should help eventually resolve some bottlenecks. But price controls naturally reduce the overall net inflow from where it should be, which should worry the CBR as well. If household debt rises further on top of continued price increases for both consumers and producers, then the relative stress on consumer demand for non-essential goods from other sectors rises. It’s important to think of indebtedness in the Russian context in terms of sectoral balances and the relationship between public and private borrowing and economic growth. Another great example is the ongoing struggle to introduce take-or-pay clauses for railway delivery contracts as a hedging mechanism for producers unsure about consumer demand and RZhD worried about its profits. If it adopts the 30% model i.e. pay if you take less than the agreed volume, the estimated liabilities to producers/retailers would be worth double RZhD’s debt portfolio, creating cascading supply chain risks that end up filtering into household balance sheets. There really is a perfect storm brewing trying to manage financial risks without sufficient space to allow market mechanisms to self-adjust or the use of stat resources and direct intervention. The closer you look, the worse it gets.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).