Top of the Pops

Apologies for the interruption of service yesterday. I had an appointment that turned into 3+ hours of tests that threw off the daily schedule. Tomorrow I’ll go back to the Russia coverage, this brief is a lot more politics than macro. I’m going to try harder to more regularly do Eurasia coverage so it’s easier to follow macro throughlines given how many countries there are to cover.

Armenian prime minister Nikol Pashinyan ended up agreeing to formally step down from his post in April while staying on as acting PM until the June 20 elections that have now been called take place. It’s a variation on the potential outcomes slightly different than what I expected in this scenario, but it makes a great deal of sense. Save face, calm the protestors, and buy time to prepare for life after Election Day and see who seems likeliest to emerge a winner. Now there’s just the fears of opposition figures, led by Vazgen Manukyan, who believe Pashinyan will make use of administrative resources to rig or else affect the outcome of the vote to contend with. It’s funny seeing Russian coverage from Nezavisimaya Gazeta going out of its way to argue that the June 20 date isn’t yet materially true, but rather a vague agreement, and that the ongoing campaign to hold elections and remove Pashinyan has thus far failed. Compare this with coverage of Lukashenka’s latest efforts to secure personal guarantees from Washington as he pivots back to multi-vector politicking in hopes of maximizing his and Belarus’ room for maneuver and it’s pretty clear that Russia’s press and Moscow’s political establishment would much rather the devil they know than competitive elections.

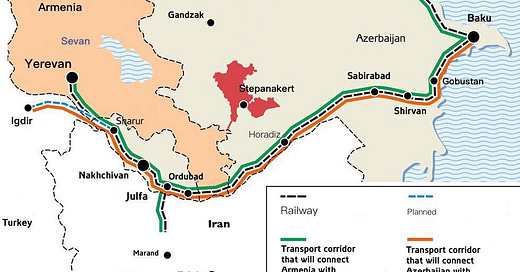

The economic implications of the current wave of political activity and outrage at Pashinyan’s government suggest that June 20 matters a great deal more than the typical “Russia won Karabakh” takes suggest. A week ago, Pashinyan was touting the promise of new rail connections to Russia and Iran via Karabakh that would change the economy — ultimately these are linked to Russian investment plans. Now the economic ministry is promising growth greater than 10% for the year, citing February data that shows the economy was still down 5.3% year-on-year alongside confident assurances that the economy is almost back. I don’t think ‘growth’ is going to save Pashinyan by any stretch, especially since Armenia took the biggest % GDP hit of any EAEU member, but the confluence of events now creates a situation where any new government is going to have to act as quickly as possible on economic matters. There’s not going to be much of a ‘lift’ from Russia’s economic recovery later in the year and it’ll be very tough balancing the need to assert and protect the nation’s pride and its interests in Karabakh/Artsakh with potential negotiations to open up the nation’s borders for freer trade and new investment that requires engaging both Azerbaijan and Turkey:

The current Minister of Justice Rustam Badasyan accused Azerbaijan and Turkey of fostering hate and abetting terrorism in the South Caucasus at the UN Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice in Kyoto a few weeks ago. If that’s the line the incoming opposition want to take assuming a new government wins, then Armenia might waste its opening to significantly change the regional balance of economic and structural power, parking aside for now questions about Russia’s security role, if that view contributes to how economic matters are securitized.

It’s easy to picture Russia as the likeliest “winner” of the next election, but it still remains too soon to tell. Iranian speaker of the Majlis Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf noted in an interview that Iran was ready to join the EAEU — I remain skeptical until we see figures from the executive branch outside of the Majlis openly commenting on this — and if it was to do so, it needs a strong partner in Armenia. Until a president, foreign minister Zarif, or other executives wielding more substantial power make these claims, there’s little reason to believe substantive progress towards this end is happening. One way of interpreting this, to my mind, is that if Iran is to “win the peace” after Turkey significantly deepened its relationship with Azerbaijan, it needs to have a formal and institutional framework to expand market access for Armenia and justify infrastructure investments into the largely undeveloped border. Iran is now trying to open/expand consular ties with Georgia, not a great sign for material progress since there’ve been what appear to be politically motivated cuts from the Georgian side to trade with Iran, but it’s important diplomatically since the resolution of the conflict could open up new routes to the Black Sea via Armenia. The post-Karabakh war settlement opens up lots of new possibilities for the South Caucasus, even if they aren’t yet fully clear or easily achieved. Any opposition leader willing to test the boundaries of the current trilateral agreement post-Pashinyan will be much harder to deal with, both to keep the peace as well as for deal-making. The Biden administration appears to be moving towards full recognition of the Armenian genocide and Iran does not want to see Turkey cement its larger role in the region on top of the already expansive security and military ties between Azerbaijan and Israel. I expect things to get crazier after June 20.

Around the Horn

As Uzbekistan tries to wrest the mantle of regional economic leadership in Central Asia from Kazakhstan, Mirziyoyev’s government keeps dipping a toe into initiatives to work out how to green the economy and build the perfunctory green targets into post-COVID economic policymaking, presumably including the adoption of green financial instruments. A new MoU between the Ministry of Finance and UN’s Development Programme concerning eurobond issuances in support of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), signed two days ago, speaks to the ongoing diplomatic and administrative hustle to maintain the hottest growth narrative in Central Asia. The World Bank, EBRD, IFC, ADB, and Abu Dhabi Future Energy company all came together in January to agree to financing for a 100 MW solar PV plant in Navoi, intended to accelerate the country’s efforts to wean itself off of thermal power plants. There’s a related new regulatory change from MinEnergo being debated through April 4 by the Oliy Majlis to mandate that from August 1, all non-household consumers pay one-time fees to connect to the grid. It’s a low-level change that makes it slightly easier to finance network expansions given the country’s continued demographic growth and considerable investment needs to substitute existing thermal power capacity as well as meet marginal increases in electricity demand. Two weeks ago, Mirziyoyev held a bilateral videoconference with German chancellor Angela Merkel, whose successor will undoubtedly be of great interest to Tashkent since they’re hoping Germany can lead EU efforts to engage Uzbekistan and help it develop a green industrial base. The green angle for Uzbek investment is the one to watch in the year ahead, especially since China’s natural gas demand growth no longer looks strong enough to support much in the way of greater gas exports from Central Asia. That’ll accelerate changes to investment plans regionally and at the national level once export earnings enter long-run decline.

A month ago, the privately-held Kazakh firm Meridian Petroleum reported making the largest oil & gas discovery in Mangystau region since independence. Of course, official releases won’t say just how much is there. Any find is huge news for the obvious reason that Soviet-era fields, like their counterparts in Azerbaijan and Russia, are depleting and production costs to maintain output are rising. But which foreign investors and firms are interested in acquiring these assets given market uncertainty? BP’s already walked away from finds it had tentatively agreed to develop with KazMunayGas linked to the long-suffering Kashagan cluster as part of its pivot away from hydrocarbons. Even pre-COVID, Shell had walked away from the Khazar field due to high production costs. Kazakh projects just aren’t that attractive. The risk of stranded assets, declining equity values and returns for Kazakh oil projects, and stress on fiscal policy and macroeconomic stability are worsening now. But the impact will be unevenly felt, particularly for Azerbaijian since its got relatively low production costs and offshore production can’t be ramped up or down like conventional onshore production in light of OPEC+ cuts because of the economics of offshore drilling. The following is World Bank data, so it’s messy and not totally accurate, but it captures an important trend that was oddly ignored during the Great Eurasia scare of 2013-2018 when BRI takes ate the discourse:

Despite the ostensible rise in transit opportunities and new growth drivers coming out of China, oil rents’ share of FSU hydrocarbon exporters’ GDP rose after 2014 with the oil price recovery (though to lower levels than before due to a lower, inflation-adjusted price band) and were trending upwards pre-COVID. Mangystau is in particularly urgent need of continued investment to sustain incomes, local revenues, and jobs, but there’s little reason to believe newer oil fields will bring much wealth to the region because of the new demand and price reality. What I’ve come to call the “Great Stagnation” in Eurasia is the rent trap that COVID’s sprung on regional economies — if you have to subsidize hydrocarbon industries or else prop them up while foreign investors begin to look away and the profit per barrel realized from your production is lower than elsewhere as well as geologically complex (as is the case in Kazakhstan), you’re in serious trouble. What’s worse, the inflationary wave hitting Russia is hitting Kazakhstan harder in relative terms. In Nur-Sultan, the richest city in the country on a per capita basis, the average person still spends 44.3% of their earnings on food. The 2021 growth forecast of 3.1% hints at an even weaker growth arc post-pandemic.

Azerbaijan’s weathering the current inflation crisis far better than the rest of former Soviet Eurasia, at least from what I’ve seen. Inflation in February was 4.2% vs. Feb. 2020, within the Central Bank’s target range. The situation’s a bit weird, though. The manat’s pegged to the USD, reducing currency volatility and offsetting some losses in spending power on imports from economic contraction thanks to a stronger than expected USD. Food accounts for about 14% of what Azerbaijan imports in terms of goods, a figure that undersells its role in domestic inflation levels but, just as importantly, doesn’t reflect that the topline inflation figure trails that of food price inflation significantly. Apologies for the fuzziness, the graphic is still useful to check developed market currencies vs. equities, noting that a weaker dollar has tended to benefit equities in the last year:

Higher US bond yields on rising inflation/growth expectations makes the yields more attractive to investors, thus bringing more capital into the US out of emerging markets where yields would normally be a fair bit higher. As this differential narrows, the USD benefits and Azerbaijan gets to ‘joyride’ on the United States’ exorbitant privilege by insulating itself from some of the same types of currency and price level volatility more evident in other FSU economies. That doesn’t mean inflation isn’t happening and isn’t a problem since the real exchange rate and income levels still matter, and the topline inflation figure is only as low as it is because of the recession experienced by the domestic non-oil industrial sector — a 12.1% contraction at its worst, with transport and storage taking a 10.9% hit — and other businesses slammed by COVID and last year’s oil shock. It’s useful to remember that the national wealth fund SOFAZ is used to help manage the national money supply and reserve balance, far easier when growth is more stagnant thanks to the post-2014 oil shock growth regime than when growth is rapid. Some domestic price controls are similarly managed using this arrangement. Saudi Arabia and other oil exporters with pegged currencies are experiencing food price inflation levels above 10% while topline inflation is often around 5-6%. It’s actually quite difficult if you dig around Russian sources to find good reporting on the price level situation, but it’s safe to say that while a stronger dollar provides some help buying imports, it leaves Baku at the mercy of the Federal Reserve. That’s why the Central Bank didn’t touch the discount rate corridor from 5.75-6.75% — note that the Fed has it at 0.25%. They’re keeping an eye on the money supply, and prices are still rising.

All told, it looks like Ukraine suffered a 4% GDP contraction from the COVID shock while the growth forecasts for 2021 generally fall around 4% as well. That means a return to pre-COVID income levels sometime in 2022, if then. There’s plenty to dive into on Ukraine at the moment, from the nationalization of Chinese-owned Motor Sich to macroeconomic concerns and fights with the IMF to Zelensky’s fight for political survival, but what I’m interested in seeing play out is the formation of a separate Bureau of Economic Security folding in functions from the SBU and other agencies aimed at tracking and enforcing the law for economic crimes. These are broadly defined but generally aimed more at things like money laundering, mass tax evasion, or else informing/shaping the regulatory and legislative process to protect national security in the economic sphere. Since the US sanctioned oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky 3 weeks ago, the pressure’s on in Kyiv to keep showing Washington that Zelensky’s serious about fighting the country’s oligarchs. Today’s call between Biden’s national security advisor Jake Sullivan and Andriy Yermak from the Presidential Office reiterates the Biden administration’s intent to push for reforms. The new bureau is consistent with the new pressure to curry favor in Washington. It’s also an interesting form of ‘mirroring’ from Russia and other FSU governments since it explicitly securitizes the economy in terms of policymaking. On March 10, an economic security strategy through 2025 was adopted. These oddly resemble Russia’s efforts to do the same and provide a new political cudgel to push through various reform efforts, initiatives, or else reward domestic business lobbies looking for rents. In other words, it’s a crisis measure when the lack of viable sources of sustainable growth are lacking. In this case, this is as much about the EU leaving Ukraine in a halfway house as it is the country’s messy economic divorce with Russia. Zelensky is expected to talk to Biden by phone soon, though when is unclear. I’d watch closely for what, if any, announcements come next.

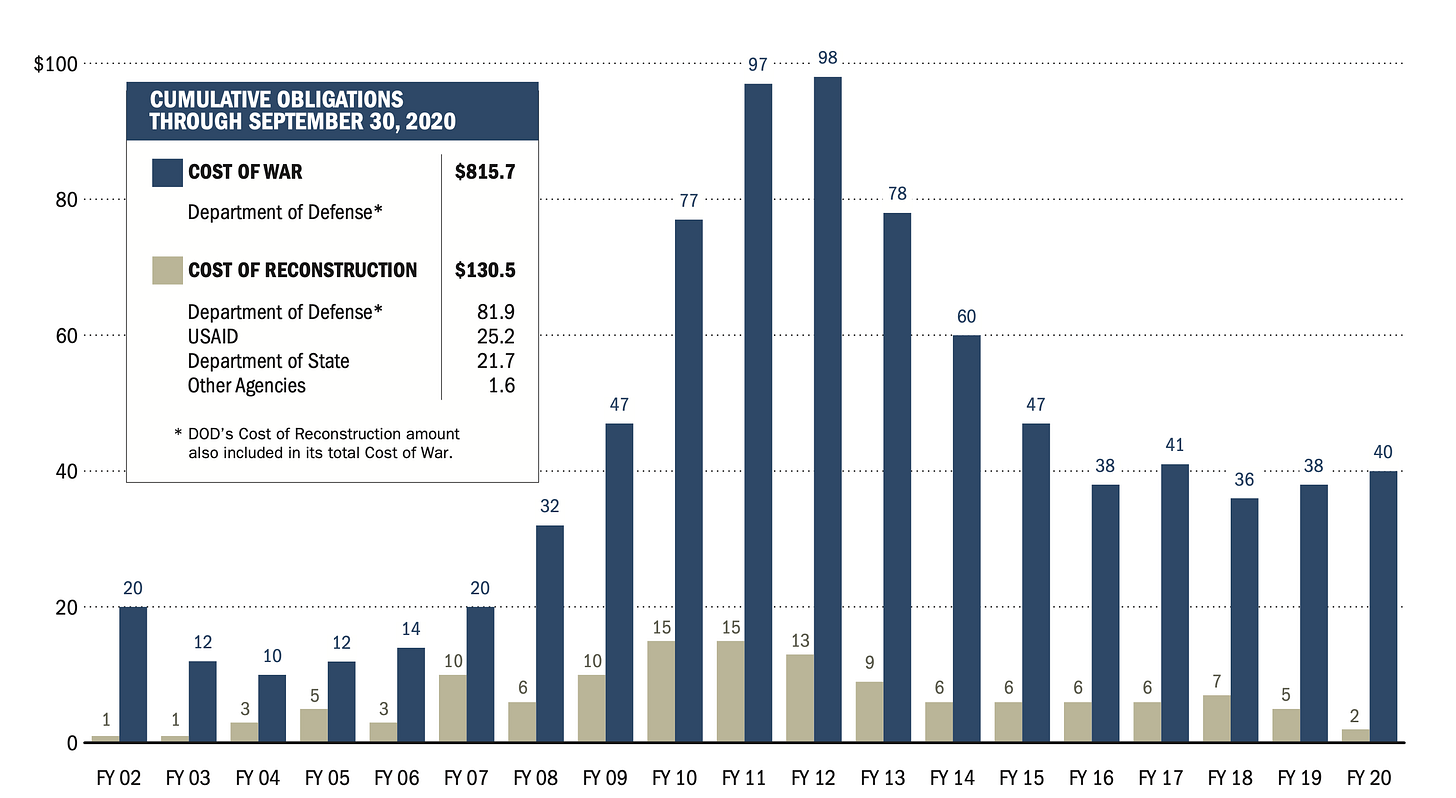

Close, but no SIGAR

US policy on Afghanistan continues to hurtle into the unknown with the tacit recognition that there will be no withdrawal and once the current May 1 date per the original agreement passes, any semblance of trust for further talks will evaporate. Biden’s telling people that US troops will be out by next year, but it’s a rather incredulous position to take since the exact same threat of disorder and violence — the Taliban have always talked as they fought and talked at the same time and would immediately go after the government in Kabul — remains no matter when US troops leave. There’s no appreciable evidence that Afghan security forces are able to stand up on their own without large US support on the ground and providing air support. For context, between 2005 and 2020, the US provided most funding for the Afghan military and the total officially amounts to $81+ billion, a figure that understates the extent of US spending on intelligence or other operational support integrated into its functions as well as the impact of USAID efforts that then force the US military to take on a larger role in coordination with the ANDSF. You have critics of any US withdrawal pointing out that the absence of any political consensus make an interim government including the Taliban impossible, while think tankers in Washington proffer ideas about a power-sharing agreement knowing that any agreement will have to be underwritten by US security guarantees for the security of the Ghani administration in Kabul. What’s worse, it’s clear from data under Trump (limited up to Feb. of last year from this report out of Brown) that the US ramped up airstrikes and civilian casualty counts trying to force the Taliban to the table without a large ground surge and without much success:

What’s more, it’s the Afghan Airforce responsible for most of the deaths in 2020 — admittedly a small sample — per the data:

Together, it’s obvious that ground forces aren’t in any position to beat the Taliban in a sustained manner and that the country faces urgent development needs that can’t be physically secured without a stronger Afghan military or a lot more US/NATO troops. It gets even hairier when you look at the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) report to Congress on 4Q 2020 that dropped at the end of January. Congress has been losing interest in funding on-budget assistance over the last 5 years and the cumulative funding costs for the conflict are astronomically high for a mission that has no definable end:

Biden’s team catastrophically blew the negotiations Trump’s team started by unilaterally handing president Ghani notice that he’d be pushed into a peace process that would force him out of power and rip up the existing governing institutions that are already lacking in capacity and resources on March 7. This situation is heading for a worst of both worlds approach: promising to leave while staying without any credibility. Even Moscow supports the proposal for a transitional government. That should tell you just how worried they are about events spiraling out of control since they know the US can’t leave in the current circumstances. They may protest US presence, but the alternative is Russia launching airstrikes in Afghanistan as civil war rages.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).